Publisher’s Note

Dear Reader,

Welcome to the Summer 2011 issue of UNCENSORED magazine. In our second year of publication, we continue to offer a unique look at family homelessness and poverty. This issue includes a feature on the use of the arts, from music to collage, in helping homeless children and youth find their voice during unsettling circumstances. UNCENSORED also investigates New York City’s housing subsidy policies in the context of the national debate about Housing First strategies. The value of volunteers to both staff and clients at the shelter level is explored, and a new program offering free, fresh milk to New York City families in need is spotlighted.

We added a new feature to our “Resources and References” section, a map that points to all the cities and towns where people and programs reported on in the magazine are from in order to show the diversity of resources available. Only when the map is completely filled with dots will all the incredible stories about family poverty and homelessness in America be told.

Thank you for your continued readership and to the many, many new readers who are added each week. And thank you to Rainbow Days of Dallas for honoring the Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness and UNCENSORED magazine with a 2010 Promise Award for National Partnership, which we received at a ceremony earlier this year.

Sincerely,

Ralph da Costa Nunez, PhD, Publisher

President and CEO, Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

The Art of Creating Stability: Homeless Children Find Confidence, Trust, and Expression through Arts Programs

by Carol Ward

Twelve-year-old “Jose” likes to rap. At the shelter in which he currently resides in New York City, the boy participates in music classes offered weekly by Art Start, a nonprofit group that provides art programming at three shelters in the city.

“I like to rap and do drums,” Jose says. “I rap about living in the shelter,” he says, noting his frustrations with his current situation. Putting his thoughts in rap form makes things “a little bit” better.

Free Arts of Arizona finds that children respond differently to various types of art, so they encourage children to create artwork using multiple media. Tissue paper, construction paper, and marker were used to create this collage.

Across the country in Portland, Oregon, a homeless young adult who goes by the name of Jukeboxxxe has found a sanctuary at p:ear, a group dedicated to building positive relationships through art and education with homeless and transitional youth up to age 24. Jukeboxxxe, who became homeless as a teen, says p:ear is an escape from life on the street.

“It’s kind of a sanctuary where I can work on my music and hang out with friends and not have to worry about influences that are easily found on the street,” Jukeboxxxe says. P:ear has a music room as well as areas devoted to other arts, and Jukeboxxxe uses the facility to practice for his stints as a street performer.

Arts programs that attempt to positively impact the lives of homeless children and teens can be found in a few major cities, super-sizing the less formalized “arts and crafts” sessions offered in some shelters and homeless outreach facilities. Options run the gamut, from painting and drawing to theater to music and dance. A few are formalized “teaching”’ programs but most just seek to provide a creative diversion and a bit of therapy for some of society’s most vulnerable children.

The art programs can also fill an educational gap caused by the pullback by most school districts in art education. According to a recent report from the National Endowment for the Arts, just 49.5% of 18-year-olds in 2008 had arts education between 1990 and 2007. That compares to 65% of 18-year-olds who had arts education between 1964 and 1981, the study said. While that study encompasses all children, no matter what their socioeconomic level, other studies suggest disadvantaged children are bearing the brunt of the cutbacks. A 2009 report on Access to Arts Education published by the Government Accountability Office found that teachers at schools identified as needing improvement and those with higher percentages of minority students were more likely to report a reduction in time spent on the arts.

Creativity and Stability

When working with homeless and at-risk children and teens, the art itself often takes a backseat to other, more basic goals. “We’re not trying to make them into little painters or bass players,” Johanna de los Santos, executive director of Art Start, says of the homeless children who receive instruction from the group’s artists and volunteers.

“First and foremost our goal is just having regular programming in a place that is inherently unstable,” de los Santos says. “In the city shelters families don’t have a lot of freedom, and they don’t really know from one week to the next whether they’re going to be living there or not. But they know we’re going to be there, they know they’ll see the same faces and there are the same rules and expectations when they show up.”

These artworks completed by homeless children from ArtBridge Houston, DrawBridge in San Francisco, and Free Arts of Arizona show the universal importance of love and positive relationships to children.

That is a key benefit at shelters operated by A New Leaf in Arizona. Homeless children living at six different shelters receive arts instruction from Free Arts of Arizona, a mentorship program for homeless and abused children. Free Arts commits to a multi-week program and sends the same volunteers each week.

“This is a committed volunteer who comes in and builds relationships with the kids,” says Torrie Taj, executive vice president for resource development for A New Leaf. “These kids have lots of people coming and going in their lives and they need stability. We really appreciate and honor that they have a consistent volunteer come in for a set number of weeks to do a project. It’s a really big deal with the kids.

“In many cases, stability has been lacking in the lives of these kids,” Taj continues. “Any time we can offer a stable base, a stable relationship, it’s a healthy thing.”

Like Art Start, Free Arts of Arizona uses “art as the vehicle,” but it is also less about art and more about filling other needs of children, says Executive Director Barbara DuVal Fenster. Although focused on bringing art in its broadest form to children, the massive program, involving 550 active volunteers, also includes shelter outreach, summer camps, and other programs.

“Our intention is to give these children the message that they matter, that they’re important,” DuVal Fenster says. “We want to give them a little bit of self-confidence and help them have a little bit better understanding of themselves. We use a whole variety of art because kids respond to different things.”

Funding Challenges

Demand for these “extra” services is on the rise in many communities. “The need never ends,” says Beverly Bentley, executive director of ArtBridge Houston. “We have a waiting list of shelters that would like to be served.” Of course, funding can be a challenge, especially given the current economic climate. Bentley says foundations have been scaling back their commitments, especially multi-year commitments. “It’s very competitive right now,” she says, noting that many nonprofits are struggling as the homeless population expands and the economy falters.

“The larger foundations used to do multiyear grants, which were valuable to an organization like ArtBridge because we’re tiny and we operate on a very lean budget,” she says, noting the pressures of constantly seeking funding. But Bentley says that the Houston community has always come through.

Free Arts of Arizona runs various art classes for children and youth ages 3 to 21.

In programs such as ArtBridge Houston and its counterparts in other cities, the instructors and materials are provided by the program operators free of charge to shelters. Shelters simply provide the space necessary for the visiting programs.

But sometimes, shelters get involved on the funding side as well. Brian Greenberg, director of programs and services for Shelter Network, a group of shelters serving the homeless population of the San Francisco peninsula, works with arts-education provider DrawBridge in seeking funding so that DrawBridge can continue to offer programming in several Shelter Network locations.

Greenberg says both Shelter Network and DrawBridge write grants for funding for the program, and says “it’s not an impossible thing” to get funded. “Art therapy for kids is kind of a sexy thing for funders to fund,” he says. “And it’s not all that expensive. For us, a grant of $6,000 or $7,000 can pay for art therapy one night a week at each of four shelters for a year, with $1,000 left over for materials.” (At press time, DrawBridge was facing a funding crisis, and had planned to cease operations in June if funding didn’t materialize.)

Art Therapy

Shelter Network takes a proactive approach because programs like DrawBridge and others are invaluable in shelters, Greenberg says. The art opportunities afforded to sheltered children are part of a slate of programs that “ameliorate the most devastating effects of homelessness,” he says.

Provider and shelter workers say the therapeutic benefits of such art programs—whether it is allowing kids to work through problems in a non-verbal way or simply allowing them to create a project of which they can be proud—are immeasurable but important.

“It’s helping children and young adults feel their potential,” says Bentley, who adds that many of the children served have received very little positive reinforcement in their lives.

Penny Fellbrich, children’s coordinator at Family Crossroads shelter in Daly City, California, believes the program is therapeutic to children dealing with trauma.

“They get to express their feelings non-verbally,” Fellbrich says. “The children don’t always realize when they’re just happily making art that they are kind of working through some of their own feelings and experiences. There is a kind of distance. They get to express some of the things that have happened to them in an unconscious way.”

Operators of several programs say a key aspect is allowing the children to make choices about their art. This may seem basic, but for a youth population that rarely gets to make choices about simple things—such as what to eat or wear, or which activities to participate in—having the freedom to explore creative options is a big benefit.

Usually, the art programs brought to the shelters start off with structured lessons, but they do not always end that way. Pamela Morton, executive director of DrawBridge, says participants are free to veer from the path. “Ours is an expressive arts program,” she says. “The facilitator comes in with a project, and if the child at the shelter wants to opt out of the project they can do something else,” she says. Morton says facilitators and volunteers are taught to be non-judgmental and to encourage children to tell a story through their art.

Carly DeLuca, a staff teaching artist for Art Start, provides music instruction at a shelter in New York’s Chinatown. She starts with a lesson but lets the kids take it from there, with the hope that the kids will express themselves through music. Her instruction also allows for creative displays of emotion, allowing kids to take out their anger and frustration. “It’s amazing how good it can feel to bang on some drums,” she says.

The Art Start program is about creating choices, says de los Santos. “In that process we’re also achieving one of our other major goals, which is helping them realize their own voice. If they’re given choices they start to find their voice and then they learn to trust that voice.”

The result can also be as simple as a self-confidence boost for children who are not accustomed to a lot of positive reinforcement. “Jenny,” another 12-year-old living in a New York City shelter, shows up faithfully to the art programs offered by Art Start. “It makes me feel good,” she says. On painting and drawing, Jenny says, “Sometimes I think mine is so ugly but then they say it looks good and I think they’re right.”

Serving the Disenfranchised

Older homeless teens and at-risk youth who are living on the streets or in precarious situations also have access to unique arts-centric programs in some cities. Pippa Arend, one of the founders and a mentor at p:ear, where Jukeboxxxe spends many hours a week, says the group’s downtown Portland facility is run like a community center, with structured classes and programs such as photography and music, as well as job training programs. The group attracts working artists as mentors, and has an on-site gallery where youths as well as professional artists can display and sell their art.

Like the shelter programs, Arend says the art at p:ear is just a means to an end. “The art is great and important, but our real goal is for these kids to develop personal relationships with others, because from that place they can move forward and mature,” she says. “Art and recreation and education are just tools for our secret mission, which is to create trust and a sense of hope for these kids.”

Sanctuary, an art center for homeless youth in Seattle, also has an ulterior motive. “We work with kids on different arts projects—for example, screen printing or performing arts—to develop a relationship and provide a safe environment where they can start to process the trauma they’ve been through, and/or just develop a sense of family and accomplishment,” says Executive Director Troy Carter.

“We’re there to say good job when someone completes a project, which seems like a simple thing but it’s a pretty big part of what we do,” Carter adds. “We do that for every kid that comes through the door.”

Homeless Youth Draw Outside the Lines of UNCENSORED Magazine

This Web-extra takes a look into two of the organizations featured in “The Art of Creating Stability,” the Sanctuary Art Center in Seattle and p:ear in Portland, Oregon. Both organizations provide more than a warm, safe place for homeless youth. Upon entering these art centers, street-involved youth gain mentors that support their creativity and individuality. They provide homeless youth with an outlet to express themselves and grow as individuals. The artworks that are created at these centers give great insight into the artists’ daily lives and portray the intelligence and strength that lies within them.

Sanctuary Art Center

www.sanctuaryartcenter.org and www.sanctuaryartcenter.org/gallery.htm

Visual arts, theater, music, and youth-employment programs are available at the Sanctuary for homeless youth and young adults ages 13–25. The instructors place a strong emphasis on building relationships with their students, making the artwork only part of the ultimate goal.

The Sanctuary Web site includes an online gallery of artworks completed by their students. One of the pieces, entitled “Chose,” composed by pen and collage on paper, shows not how makeup can enhance facial features, but what makeup is actually covering up. Another piece, entitled “Alice,” composed with mixed media on paper, portrays Alice from Alice in Wonderland falling into a world in which she does not belong.

p:ear

Youth who are homeless or transitioning out of foster care find inner peace and an outlet for self-expression at p:ear. Directors Pippa Arend, Beth Burns, and Joy Cartier make sure every young person that enters their doors receives an opportunity to learn and create something meaningful, whether it’s in the music room or in a barista training class, a collaborative program between p:ear and a local coffee shop.

The p:ear Web site includes an online gallery of artwork and a video in which youth explain the impact p:ear has had on their lives. While being interviewed for the video, one teen says, “Without p:ear I would still be doing drugs, engaging in unhealthy behavior, and I would still feel a little dead inside.” Another teen in the film remarks, “Without p:ear I would not have had the motivation to go to college.”

Resources

Art Start; www.art-start.org ■ p:ear; www.pearmentor.org ■ National Endowment for the Arts; www.nea.gov ■ U.S. Government Accountability Office; www.gao.gov ■ A New Leaf; www.turnanewleaf.org ■ Free Arts of Arizona; www.freeartsaz.org ■ ArtBridge Houston; www.artbridgehouston.org ■ Shelter Network; www.shelternetwork.org ■ DrawBridge; www.drawbridge.org ■ Family Crossroads Shelter; www.shelternetwork.org ■ Sanctuary Art Center; www.sanctuaryartcenter.org.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

Working to Eradicate Food Insecurity from Inside the Heart of New York City

by Lee Erica Elder

Times are hard for Oscar Palacios. The Bronx resident lost his job two months ago, and his wife was let go from her job last week. While they look for work and file for benefits, putting food on the table for themselves and their 12-year-old daughter is now that much more difficult. But Palacios sees signs of hope, as do thousands of other New York residents benefiting from the Milk from the Heart program, which provides free milk to low-income families with children.

Now more than ever, families need Milk from the Heart. The Palacios’ story is not unique. According to the Food Bank of NYC, more than half of NYC households with children have difficulty affording food. These numbers reflect an alarming growth throughout the United States. The Department of Agriculture (USDA) found in 2008 that 17.3 million Americans lived in households that were considered to have “very low food security.” This was up from 11.9 million in 2007 and 8.5 million in 2000. Families with children fare even worse. They struggle with food hardship at a rate 1.62 times that of other households—24.1% in 2010, up from 14.9% in 2009, according to the Food Research and Action Center.

Founding Manhattan sponsors of the Milk from the Heart program, Leonard and Allison Stern, hand out free milk to New York City families at one of the program’s distribution locations.

The impetus for the program came from philanthropist Leonard N. Stern, founder of Homes for the Homeless (HFH), a New York City provider of social services and transitional housing. HFH began piloting Milk from the Heart in the spring of 2010 to address the lack of dairy found in the diets of children from homeless and low-income families, and currently delivers to 16 sites.

The program is designed to make people feel comfortable accepting assistance, rather than embarrassed or stigmatized. “We take data but we don’t ask for names and they don’t need to show I.D.,” Program Coordinator Jonah Nelson says of clients.

“Our kids are not eating as well as they should.”

Staff, volunteers, and coordinators welcome families and answer questions, translating as needed. With gestures as simple as a smile or handshake, volunteers can show they remember repeat visitors and greet them like old friends. Even the delivery vans are friendly, featuring colorful murals of children from all walks of life.

“I’ve been with them on a couple of deliveries and this program is going into areas where they’re not getting fully served by some of the existing programs out there,” says Richard Naczi, chief executive officer of the American Dairy Association and Dairy Council, Inc. “For people that feel disenfranchised, the milk is important, but the outreach is also important, showing people that you care. There is such a face to this program, which is different than some of the more bureaucratic programs. I think that makes people more comfortable.”

The Milk from the Heart van parks at one of the program’s distribution sites where families are already in line around the block.

The partnerships and connections fostered with local community-based organizations, schools, shelters, and other programs help deliveries run more smoothly and counter the stigma associated with free food programs. Parents at PS 96, mostly Central American immigrants (the school’s population is 76% Hispanic), are initially wary and intimidated, fearing legal trouble if they participate. PS 96 Parent Coordinator Sonia Kemp bridges this gap by encouraging them to get milk and by facilitating workshops on nutrition, immigration, and other topics. “This community is low-income, but because of this economy, we also have some families that have lost jobs, they’re fighting for welfare now—a lot can’t understand what’s happening because they’ve been in a job for so long,” says Kemp. The project is so successful that parent coordinators from other schools have expressed interest in free milk.

Down on the other end of Manhattan, on the Lower East Side, delivery locations run in collaboration with University Settlement and Educational Alliance, serving a different demographic. The neighborhood is home to a largely Asian—particularly Chinese—population, as represented on the milk lines by grandparents who run households and watch children while the parents are at work, oftentimes out of state.

“Kids are overfed and undernourished.”

“Although the Lower East Side is gentrified, there are many families living in multi-generational homes, most of whom are low income or immigrants,” says Magdalene Gomes, director of social services at University Settlement Early Childhood Center. “Unfortunately, we sometimes have to turn people away because we run out of milk,” Gomes said. “When we started the program I had assigned two staff to provide Chinese and Spanish translation. Now I have at least four people working the distribution lines.”

Over at the Educational Alliance, demand grew from 120 families to 240 within two weeks. People line up hours ahead of time, afraid they will not make the cutoff. “There is an immense need,” says Stacey Li, director of social services at Educational Alliance’s Head Start programs.

Jonah Nelson, project coordinator for Milk from the Heart, distributes free milk to an appreciative family after they patiently awaited their turn.

Li estimates that most of the families served are living on about a $22,000 total yearly salary (an average household of four, including two children). “Some of the grandparents come very early, and once they get the milk, they try to go to the back of the line again because they really need the milk for other family members,” she says. Older patrons take queuing seriously—playfully using their canes to indicate that no cutting is allowed. “We really appreciate this partnership—it has been a tremendous help to a lot of our parents,” says Li.

Families struggle to make ends meet on salaries that are stretched thin, yet often deemed too high to qualify for assistance. “There’s a very serious gap between wages that people in these neighborhoods make and what it takes to survive, and we’re here to address that gap,” says Nelson. “It’s an emergency program because of the depth of the problem. Just because you don’t meet federal poverty level, which is under $20,000, doesn’t mean you have money to survive, it just means you have a place to stay and possibly some other benefits. The Milk from the Heart program is needed because there are structural problems with emergency food systems on both the city and state levels as well as nonprofit programs.”

Milk Matters

We asked several program participants what milk means to them:

Gisela Suarez lines up for milk every Tuesday because both she and her granddaughter have calcium deficiencies. “The children need calcium, for growing strong bones and healthy muscles,” she says.

Cancer survivor Luisa Bailey, 81, says she has to have milk for her breakfast and for her grandchildren, ages five and seven.

Columba Herrera, grandmother to two young children, loves drinking milk, but wants to make sure she has enough for the little ones. “Sometimes, I’m home with no milk in the house, and Naya, two years old, says, ‘Nana, Nana, gimme leche, give me milk.’ I buy five gallons a week,” she says.

Palacios agrees. “We try to fill out the forms to get food stamps and try to get another job,” says Palacios, whose 12-year-old daughter needs milk but is ineligible to receive other programs such as WIC (Women, Infants, and Children), which only goes up to age five. “But all the documents take six weeks or maybe more, and we’re still waiting. This program is good for us; I save 10 to 12 dollars a week.”

The cost of living in the New York metropolitan area is also high, so families often choose between paying bills and buying nutritious food. Bert Morales, who gets milk at the 196th Street and Grand Concourse location in the Bronx, and has lived in the neighborhood for 35 years, is currently unemployed and buys about two gallons of milk per week to feed his family of four. “We drink a lot of milk, and it’s expensive, about four dollars a gallon,” he says. “Sometimes you don’t buy certain things because of the expense. This program gives us hope.”

Families wait in advance for free milk outside of an elementary school. With the average price of milk in New York City at four dollars a gallon, families are grateful for the free milk they receive.

Choosing cheaper alternatives to milk, such as soda or sugary drinks, contributes to the expensive health effects of poor nutrition in low-income families—such as the number of obese children, who often grow into obese adults. “Our kids are not eating as well as they should,” says Naczi, whose organization works to educate families about classroom breakfast programs and other opportunities to improve childhood nutrition. “Kids are overfed and undernourished—we have a strange dichotomy where the portion of children who don’t have access to good food consume food that is inappropriate for them.

“There are a number of areas where dairy would meet nutrient requirements that would help us avoid certain disease states when we get older,” Naczi says. “A diet rich in whole grains, fruits and vegetables, and dairy—kids consuming those kinds of diets are not consuming the empty calories: juices or soft drinks with lots of sugar.”

A boy picks up free milk for his family.

Low-fat milk offered daily by Milk from the Heart aims to ease some of this nutritional burden, according to Mary Story, the program director of the Healthy Eating Research program, funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. “Low-fat and non-fat milk (1% and skim) is a healthy drink, as it’s high in nutrients such as calcium, Vitamin A, D, the B vitamins, and protein, and low in fat and saturated fat, and low in calories,” says Story, who is a professor of the Division of Epidemiology and Community Health at the School of Public Health at the University of Minnesota. “Low-fat or non-fat milk is a much better choice than soft drinks.”

Programs on the national level like Michelle Obama’s “Let’s Move” campaign are working to increase awareness of the importance of nutrition and exercise in children, but there’s still a long way to go. “I feel that the milk program demonstrates to families that we care about their nutrition; instead of handing out sugary drinks, or other free food, it’s intentional that milk is being handed out,” says Amanda Leibenhaut, a social worker for Community Schools and Youth Services of The Educational Alliance. “I hope this sends a message to families that we care about their bodily health.”

A woman and a young child leave the milk distribution site with two free quarts of low-fat milk. More than one-half of children ages two to eight do not get the recommended two servings of milk a day.

So what does the future landscape of Milk from the Heart look like? “This is not a social problem, it’s a preventable health problem,” says Stern, founding sponsor of Milk from the Heart in Manhattan, who hopes that more donors will be inspired to step up and offer funds for this much-needed program in other boroughs, and eventually other cities and states. “Without that we’ll see a generation of children who are less healthy and have shorter lifespans than their parents’ generation—something that we can’t afford,” he says.

Naczi hopes these programs will receive more funding as well. “We’re cutting back on all types of programs. Based on the commitment we’ve made as a country to doing the right thing, I hope that people find a way to help continue to fund these programs. An investment in the health and wellbeing of our children today will pay major dividends in the future. We cannot be short-sighted. We can invest wisely now or pay much, much more tomorrow.”

Milk from the Heart in Action

This video companion to the UNCENSORED article “Milk from the Heart: Working to Eradicate Food Insecurity from Inside the Heart of NYC” takes you on a virtual tour, stopping at several Milk from the Heart distribution sites. We talk with recipients about how this program changed their lives and with Project Coordinator Jonah Nelson:

Resources

Food Bank for New York City; www.foodbanknyc.org ■ United States Department of Agriculture; www.usda.gov ■ American Dairy Association and Dairy Council, Inc.; www.adadc.com ■ Food Research and Action Center; www.frac.org ■ PS 96; www.ps96.org ■ University Settlement; www.universitysettlement.org ■ Homes for the Homeless; www.hfhnyc.org ■ Educational Alliance; www.edalliance.org ■ Healthy Eating Research, University of Minnesota School of Public Health; www.healthyeatingresearch.org ■ Let’s Move!; www.letsmove.gov.

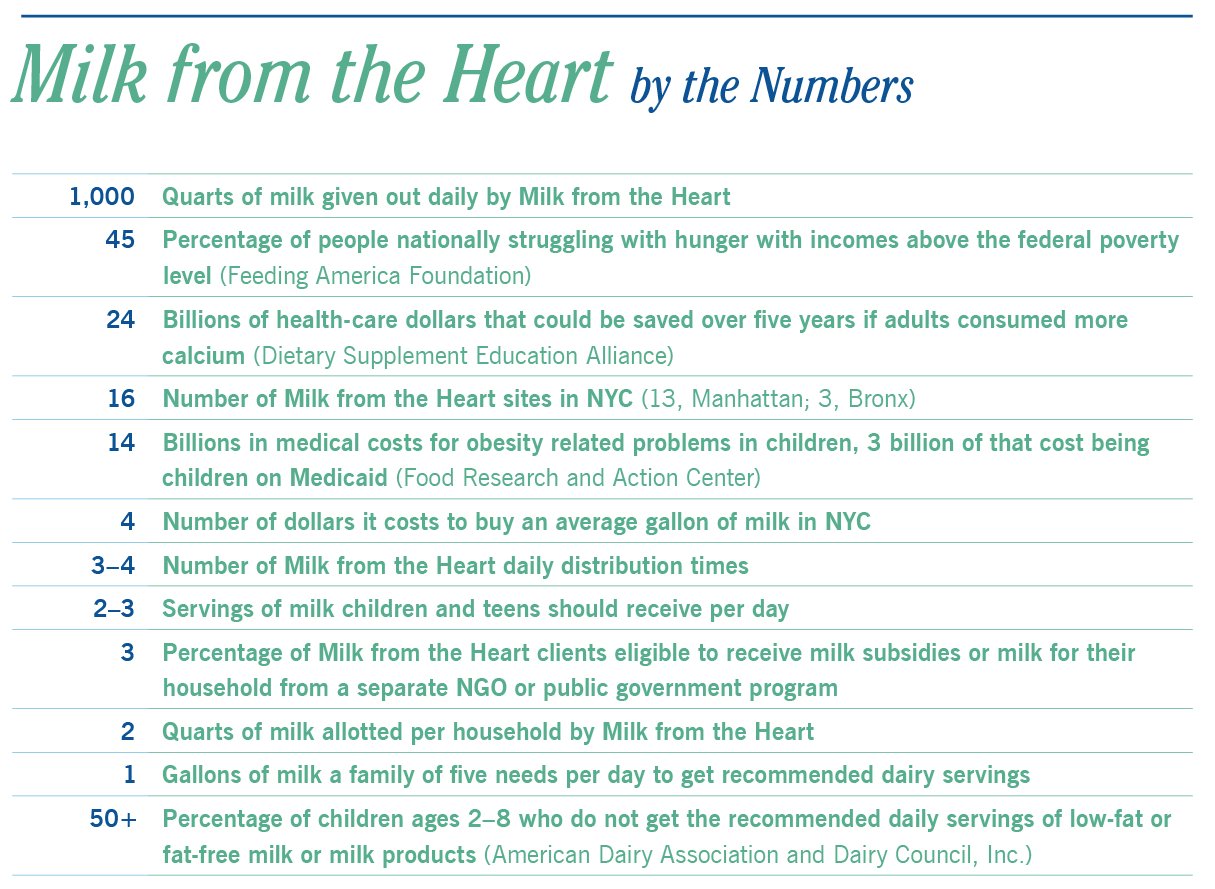

By the Numbers

Feeding America Foundation; www.feedingamerica.org ■ Dietary Supplement Information Bureau, Natural Products Foundation; www.naturalproductsinfo.org ■ Food Research and Action Center; www.frac.org ■ American Dairy Association and Dairy Council, Inc.; www.adadc.com.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

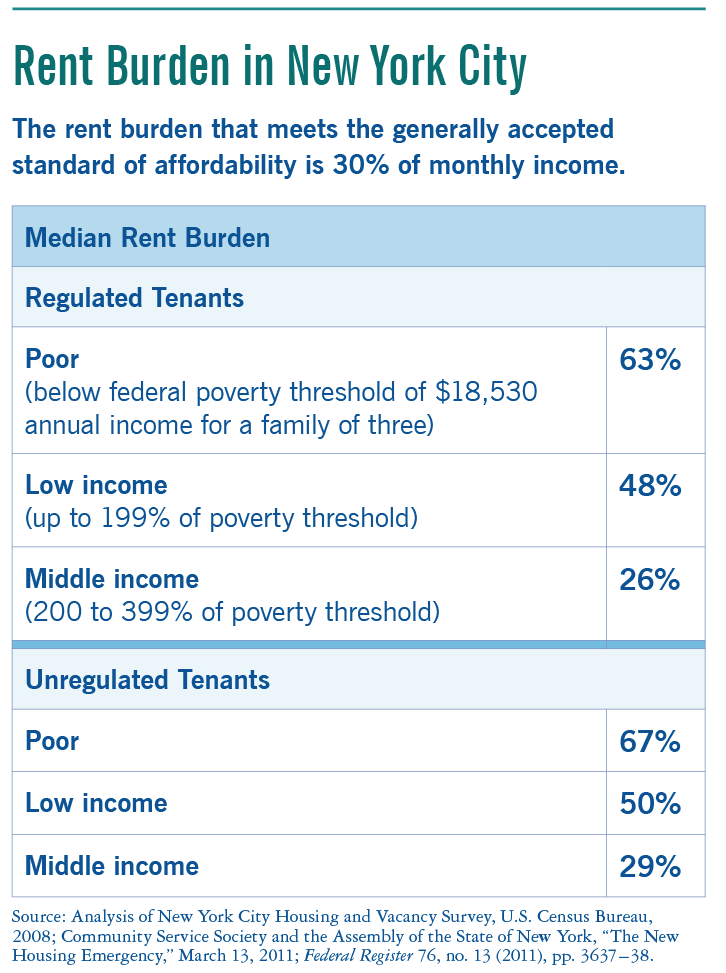

Mayor Bloomberg’s Silver Bullet Misses the Target

by Colin Asher

The first term of Michael Bloomberg’s mayoralty was a heady time. After switching political parties, and spending $73 million of his own money, the richest man in New York City had managed to win his first campaign for public office with a couple of percentage points to spare. With victory still clear in the rearview, he plunged into the most treacherous waters he could find. He took on the teachers union, instituted a $3 billion dollar tax increase and, with no threatening challengers in sight, decided to tackle one of the city’s most entrenched problems.

On June 23, 2004, Bloomberg appeared at a breakfast hosted by the Association for a Better New York, and announced that he had a plan that would dramatically reduce homelessness. With President Bush’s homeless czar looking on, the mayor described the strategy embodied within his plan, “Uniting for Solutions Beyond Shelter.”

Natalie Rizzo had been on Advantage for almost a year when she received a notice from DHS about the end of the subsidy. She runs errands on her way home noting, “Everything I need is right in this neighborhood.”

“This new plan aims to replace the City’s over-reliance on shelter with innovative, cost-effective interventions that solve homelessness,” the mayor told an audience of philanthropists, nonprofit leaders, and city movers and shakers. “And to make visible headway in reducing homelessness on the streets and in shelters during the next five years.”

Bloomberg’s strategy relied on two tactics: rapidly rehousing homeless families and deemphasizing shelters. If the City did those two things, while simultaneously improving homelessness prevention services and agency coordination, and expanding the capacity of drop-in centers, homelessness could be reduced by two-thirds in five years, he proclaimed.

Bloomberg’s plan contained all the hallmarks his early years have become known for. It broke with tradition, while claiming to be the most efficient option. It was bold, nearing hubristic—while cities across the country were planning to end homelessness in ten years, Bloomberg said he could do it in five—and, like many of the Mayor’s grand schemes, it has not aged well.

The most ambitious part of the City’s new strategy was a subsidy called Housing Stability Plus (HSP), which was designed to move homeless families out of shelter and into market-rate apartments as quickly as possible (see sidebar, page 20). There were obvious problems with HSP from its inception, and it ended after only two years. The City replaced it with a new program, Advantage NY, in 2007. When problems arose with that plan, a third, Advantage, was introduced in 2010. And now that too has ended, and the mayor will not be trying again. While housing subsidies were being created and discarded, homelessness grew. Instead of the decrease promised on that June morning in 2004, the last seven years have seen the homeless population increase to a level unseen since the Great Depression. When “Uniting for Solutions” was released, there were 36,642 people living in New York’s shelters, including 8,712 families. And in March 2011, when the last of the City’s rapid-rehousing programs went quietly into the night, the shelter census had recently reached an all-time high of 39,542 individuals, including 9,864 families.

There is irony to be found in the demise of Advantage, the last of the mayor’s housing subsidies, because the result of his efforts has been so contrary to his intentions, and because the scene of its death—room 232 of the New York Supreme Court building—was so contrary to that at its fêted birth.

Advantage Has Its Day in Court

On Thursday, April 21, 2011, ten lawyers, five representing the city and five representing Advantage recipients, sat before Judge Judith Gische’s bench waiting for her to address them. The question before her Honor that afternoon was whether New York City would be allowed to stop paying rent on 15,000 apartments occupied by formerly homeless families participating in the defunct Advantage program.

Six weeks before the hearing, Governor Andrew Cuomo cut the state’s portion of funding for Advantage from the budget. Through a spokesperson, the governor said, “regardless of this year’s anticipated cuts, New York City has the funds to support the continuation of this program if it so chooses.”

The City disagreed, loudly and publicly, and in response to Cuomo’s decision sent notices to every Advantage recipient telling them their housing subsidies would end in 12 days. Among formerly homeless families, there was panic.

Through a spokesperson, the governor said, “regardless of this year’s anticipated cuts, New York City has the funds to support the continuation of this program if it so chooses.”

The Legal Aid Society took up their cause, and sued, claiming that the City had signed contracts with the families in question, and could not stop paying their rents. The court could not force the City to hand out new vouchers, but at the very least, Legal Aid argued, they could insist they make good on existing obligations.

The case landed on Judge Gische’s docket, and when it did she issued a temporary restraining order requiring the City to pay April’s rent, and scheduled the April 21 hearing.

Attorneys for the City were forced into an uncomfortable position. The administration maintains that Advantage was a success, and claims that ending it would bring on a nightmare scenario. In late March, Seth Diamond, the commissioner of the Department of Homeless Services (DHS), told the City Council’s General Welfare Committee that ending Advantage was likely to “create a need for 70 new shelters.”

“By this time next year, we project the families with children population will grow by over 4,000 to a total of over 13,000 families in the DHS shelter system,” Diamond told the Council.

Both sides arguing before Judge Gische quoted Diamond’s assessment of the effect ending Advantage would have, but the City’s attorneys had to add the caveat that the judge should allow the predicted worst-case scenario to happen. The City could not afford to operate the program on its own, they argued.

Steve Banks, the balding and bespectacled attorney-in-chief of the Legal Aid Society, had an easier case to make. The City’s own estimation of the value of Advantage supported his arguments. He told the court that the City’s filing read like his own, and said that ending Advantage would mean disaster.

“I wonder what their Plan B is in June or July or August when these families start coming into the shelter system?”

He warned against “abandoning” formerly homeless families who are trying to make good, and asked the court, “Is this really what the social contract is all about?”

At the end of the hearing, Gische promised a decision by May 2, and extended her restraining order until that morning, meaning that the City had to pay Advantage rents for the month of May. Siding with the plaintiffs would mean that the 15,000 families currently receiving subsidies would get a few more months of rental assistance. Siding with the City would mean those families would lose their rental subsidies, and most likely their housing, if not immediately then soon. But no matter her decision, the short life of the Advantage program would effectively end in Gische’s courtroom. Even if she ruled for the plaintiffs, no new homeless families would receive vouchers.

A New York City Tale but a National Story

With no new subsidy on the horizon, homeless families have nothing to rely on now but the shelter system. There is irony to be found in that fact as well, because the idea guiding all three of the City’s housing subsidies was that shelters should be deemphasized, and that homeless families should be moved through them as quickly as possible.

That rapid-rehousing strategy is called Housing First, and it has been en vogue nationwide for several years. Studies have shown it to be very effective when focused on chronically homeless single adults, but results for the homeless families targeted by New York City’s recent housing programs have been decidedly mixed.

In the decades before Housing First gained traction in New York, the City pursued a fairly consistent policy of improving services in homeless shelters, and prioritizing homeless families for placement into subsidized housing. During that time, shelters transformed from intimidating spaces such as converted auditoriums, armories, or welfare hotels to safe private spaces.

In 1990, a consent decree outlawed the City’s practice of housing homeless families in congregate shelters. After the decision, homeless families were placed in shelters called Tier II facilities that, by law, provide private rooms, child care, housing services, and, if necessary, three meals a day. During this time, many shelters also provided job training, educational programming, and life-skills classes. While in shelter, homeless families were prioritized for subsidized permanent housing in buildings operated by the New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA), and for Section 8 federal housing subsidies.

By improving services, and offering homeless families housing options that were not subject to the exigencies of the free market, the City was able to lower the rate of families who returned to shelter after leaving from 50% in 1991 to 22% in 1999.

By improving services, and offering homeless families housing options that were not subject to the exigencies of the free market, the City was able to lower the rate of families who returned to shelter after leaving from 50% in 1991 to 22% in 1999. But both of those tactics were set aside as part of the Housing First strategy. Shelter services have been deemphasized, and shelter stays have been shortened as much as possible. In 2010, the city began financially penalizing shelters for every client who remained in shelter for longer than six months; that time period was eventually reduced to five months. When Advantage ended, DHS ended the length-of-stay-based payment system. As of press time, they were in the process of creating a new “performance-based” shelter payment system, the details of which have not been revealed.

The City’s fourth shelter-to-housing policy—after HSP, Advantage NY, and Advantage—has not yet been announced two months after Cuomo cut Advantage funding, but all indications are that the next plan is no plan. The 2012 Executive Budget, released at the beginning of May, did not include funding for a new housing program. And on May 11, DHS sent a letter to shelter providers stating, “the City has no plans to begin its own rental subsidy program.”

City Councilmember Annabel Palma, chair of the Council’s General Welfare Committee, confirms that no new housing program is being discussed. In meetings with Seth Diamond, Palma says, it was made clear that the City was not going to create a new housing voucher, or bolster shelter services before Advantage clients start returning to shelter. “There’s no plan,” she says.

Palma was a critic of Advantage before it ended, but, she says, “I would have never advocated for a complete elimination of the program.” She questions why the City was so quick to give up on the program after Cuomo cut it from the state budget. If it was as successful as the City claimed, she asks, why didn’t the City continue to fund it? “It’s only $210 million in a budget that’s $65 billion; it’s nothing,” she says.

In interviews, shelter providers expressed frustration that shelter-to-housing programs have changed so much and so often in recent years, that there is no program any longer, and that there is so much uncertainty about what might be coming next. The belief that they are being asked to do the impossible—transition homeless families with little education and few or no marketable skills into the mainstream of the city—and a sense of resignation crept into those conversations.

A Shift to Rapid Housing

Two weeks after DHS announced Advantage would end, Sheryl Williams and Frank Martarella, managers at the Saratoga Family Inn, one of the city’s largest family shelters, field questions about what the loss of Advantage would mean for the 255 families living in the Saratoga.

Williams is the shelter’s director of family services, and Martarella, an ex-NYPD officer, is shelter administrator. They sit across the room from each other, and lob anecdotes back and forth, one beginning a story about a client or a program that has fallen by the wayside, the other finishing it.

“Our numbers are creeping up, we have to move [clients] out any way we can,” Martarella says. “Family reunification, AWOL, … ” he trails off. Those phrases are euphemisms for sending homeless families to double up with relatives, and discharging families who have been absent from the shelter. Conspicuously absent from Martarella’s list of outcomes is any mention of employment, market-rate apartments, or public housing. Family reunification has been the top discharge from the shelter recently.

“We’re encouraging them to make amends [with their families],” Williams says.

And what about the families who have been saving, searching for apartments, and expecting to receive an Advantage voucher?

“They’re asking, ‘What’s next?’” Williams says.

This cycle—clients entering shelters and then exiting back to the same, or similarly unstable, living situations—has become the defining characteristic of homeless services in New York City. When the five-year plan was announced seven years ago, 24% of the families entering shelter had been homeless in the past; by 2011 that figure had almost doubled, to 47%.

This cycle—clients entering shelters and then exiting back to the same, or similarly unstable, living situations—has become the defining characteristic of homeless services in New York City. When the five-year plan was announced seven years ago, 24% of the families entering shelter had been homeless in the past; by 2011 that figure had almost doubled, to 47%.

And now, with Advantage gone, most stakeholders expect it to climb higher.

When DHS focused resources on securing housing as quickly as possible, services that had been available in the city’s shelters fell by the wayside. It was possible before the policy change for shelter residents to take GED or pre-GED classes in the Saratoga, or participate in job-training classes. Williams mentions back-to-work programs that trained residents in skills such as day care and building operations, but says they haven’t operated in the shelter since rapid housing became the top priority. Now, shelter staff creates an exit plan for every client during their very first meeting with a case manager.

“The focus changed to, ‘They just need an apartment,’” Williams says. “Then we’re hearing from the landlord two days later—they can’t maintain.”

Without additional services and training opportunities, she says, many homeless families are destined to return to shelter. “Formerly stable clients are few and far between.”

When asked what the policy change and shift away from service provision has done to staff morale, Martarella shakes his head.

“For me, it’s different. I come from law enforcement. But Sheryl went to school to help people, and basically we’re telling them to move out.

“So, morale … ” he unfolds his arms, and throws them wide, miming exasperation.

To illustrate the tension that exists between client need and programmatic demands, Martarella mentions a case manager who recently invested time in helping a family with complex issues. “He wanted to be a social worker,” Martarella says. “That was a problem. You can’t be just a social worker—you gotta move people out.”

Williams says that the time available to spend with clients is so constrained that everything in the case manager-client relationship has been reduced to discussions about short-term goals, savings plans, and exit plans. “It’s like, OK, when am I going to listen to this person?” she says.

“It ain’t what it was,” Martarella concludes.

Returning to Shelter

Even divorced from other social service demands, the mandate to move clients out of shelter quickly is difficult and about to get harder. Confusion over the status of Advantage has already sent some families back to shelter, giving providers a preview of what might be coming.

Patricia Boyar (a pseudonym to protect her identity while she remains in shelter), 38, is the head of one of those families. When Boyar received notice that her Advantage subsidy was going to end, she and her two-year-old daughter were living on Staten Island, in an apartment she could not afford without assistance from Advantage.

“They sent me a letter saying they’re not going to pay anymore,” she says weeks later, now back inside a family shelter.

Boyar had never signed a lease before, didn’t understand eviction law, and thought the letter she received from DHS meant she had to leave her apartment immediately.

Asked how she feels about the future, Boyar says, “Not good, because I don’t know where I am going to go.” She survives off a little more than a thousand dollars a month that she receives from the federal government because she has a permanent disability. Without a housing subsidy, or priority for subsidized housing, it is unlikely she will be able to move out of her shelter anytime soon. Even if she could find an apartment with rent within her means, there would be nothing left of her check to cover bills and basic necessities. “How I’m going to pay the light?” she asks.

Asked where she thinks she will be in a few months, Boyar shrugs, looks at the floor, and offers a non-answer. “There’s no program. That’s it.”

Her prognosis for the future is not far from that of some shelter providers.

“We’re going to go backwards,” Michael Callaghan says, and prophesies that clients will stay in shelter longer. “The shelter system is going to become the new permanent housing for many families with significant barriers, low educational levels, or absence of sustainable employment with a living wage.”

“We’re going to go backwards,” Michael Callaghan says, and prophesies that clients will stay in shelter longer. “The shelter system is going to become the new permanent housing for many families with significant barriers, low educational levels, or absence of sustainable employment with a living wage.”

Callaghan is the executive director of Nazareth Housing, a nonprofit that operates shelter, and permanent housing facilities. He is less than optimistic about the future when asked, but doesn’t care to be characterized that way.

“I’m not cynical, I’m a realist,” he says.

Citing the amount the City was thought to have at its disposal for a new housing program, he asks, “What are they going to do with 60 [million]?” Since he proposed this question the City has stipulated that there will be no new housing program, and the amount Callaghan cited was reduced to $30 million and still has not been finalized.

A Complex Problem

Unlike some of the administration’s critics, Callaghan does not place all of the blame for the city’s rising homeless census on the administration’s policies. He sees the problem as a product of larger social forces.

“If you want to be about honest numbers, the families coming into the system because of HSP, because of Advantage, they’re coming in because there is no living wage, because of climbing rents,” he says. “I don’t think you can say definitively that those programs caused an increase in homelessness, maybe recidivism.”

No simple housing voucher will solve the problems of homeless families, he says. Almost 70% of the clients Nazareth houses have no high school diploma or GED, 73% are unemployed when they arrive, and almost 80% of the families that the organization shelters are headed by a single woman. For that group of people, something bolder than a time-limited housing voucher is needed. Callaghan suggests a multifaceted, regional approach. “The solution in Brooklyn might not be the solution in Queens or the Bronx,” he says. And, he argues, a comprehensive strategy should be developed as part of a “Housing Summit” where all of the city’s stakeholders would craft a long-term affordable housing plan, an idea he mentions often and with obvious enthusiasm.

Advantage client Natalie Rizzo works part time at a neighborhood church while pursuing a degree in teaching.

In contrast to Callaghan’s bold proposals, the constant programmatic churn of the past seven years has prepared some shelter providers to accept whatever comes.

Iris Lebron Colon operates a small family shelter called Theresa’s Haven, housed inside a converted apartment building in the Bronx. The shelter’s administrative offices, cluttered with stacked papers, ledgers, children’s art, and curling photographs, began their life as a two-bedroom apartment, and Lebron Colon holds court in the backmost room.

“I’ve been doing this since ’85, ’84?” she says. Counting a few of those years on her fingers, she sighs. “My God.”

Since she began in homeless services, Lebron Colon says, things have not improved. When she started, there were only two thousand homeless families in the city; now there are ten thousand. The families she sees these days stay in shelter longer. They have more problems, and fewer resources.

“It’s tough right now because without Advantage,” she shakes her head, “they don’t have any options, they don’t have any work experience, they don’t have any skills.”

Of the 39 families staying in her shelter on any given day, Lebron Colon estimates that two will be headed by adults who cannot read or write, three will have no English skills, and more than half will have neither a high school diploma nor a GED. Having no work experience is a malady so normal she doesn’t bother to mention it. When asked, she says, “That’s common, very common.”

Since Advantage ended, she has been encouraging residents to move back in with their families if possible, and she has resigned herself to housing some families for the foreseeable future. By her estimation, no more than 5% of the families that stay in Theresa’s Haven will be able to afford market-rate apartments without the assistance of a housing subsidy.

Pointing a thumb over her shoulder at a building across the street, she says that studio units inside of it rent for about $1,050 a month. (Theresa’s Haven is located in the poorest congressional district in the United States, and is not filled with inordinately expensive apartments.) If a single mother were to work full time in a position that paid above minimum wage, her pre-tax income would cover only rent and bills in that building—nothing would be left for clothing, food could only be bought with food stamps, there would be no money for entertainment, and saving would be an impossibility.

… If a single mother were to work full time in a position that paid above minimum wage, her pre-tax income would cover only rent and bills in that building—nothing would be left for clothing, food could only be bought with food stamps, there would be no money for entertainment, and saving would be an impossibility.

“A client who has an eight-dollar job, three kids—how are they going to move?”

Answering her own question, she says, “They can’t move.”

That observation—that the cost of living in the city has raced so far ahead of the wages paid to the people who keep it running that they will never catch up—is at the core of the criticisms most often lobbed at the City for its homeless policies.

The Coalition for the Homeless has been among the City’s most strident and vocal critics since HSP, the first time-limited housing subsidy, was introduced. In the wake of Cuomo’s budget cut, it was one of the few organizations publicly wishing Advantage good riddance, while pushing for a more multifaceted approach that incorporates a variety of long-term affordable housing options.

Patrick Markee, the coalition’s senior policy analyst, says the group’s core critique of the City’s homeless strategy is it does not acknowledge that homelessness is primarily a housing affordability issue. If you concede that the cost of housing is driving people into shelters, he says, it becomes clear that permanent housing is the solution.

Asked about the City’s record of utilizing short-term subsidies, Markee says, “I think the numbers speak for themselves. We’ve got all-time record homelessness. City data shows more New Yorkers than ever slept in city shelters last year. Record numbers of homeless families, homeless children, all of this points to policies that have failed to address homelessness.”

Housing Stability Plus (HSP)

HSP was the City’s first housing voucher; it was launched in December 2004 and ended in April 2007.

In order to be eligible for HSP, homeless families had to be receiving Public Assistance (PA), and had to continue receiving it. If a family’s PA case was closed for any reason—including finding full-time work—their HSP benefits ended as well. The maximum term for HSP was five years, and every year benefits were reduced by 20% until they zeroed out. From its inception, advocates argued that receiving HSP was tantamount to becoming poorer every year because of benefit reductions. Predictably, families receiving HSP found it next to impossible to balance the HSP requirement to earn more every year, and the PA requirement that they not earn too much (lest their case be closed).

HSP was also criticized for the quality of housing offered to recipients. In 2007, an investigation by the Coalition for the Homeless revealed that homeless families had been housed in buildings owned by landlords categorized as major problem owners, and more than 1,000 families had been placed in buildings with two or three hazardous violations, including lead paint hazards, vermin, lack of heat or hot water, and broken ceilings or floors.

Advantage NY

When the City ended HSP they replaced it with Advantage NY, a short-term housing subsidy that eliminated the Public Assistance requirement. Advantage NY initially included five subprograms, each of which catered to a discreet portion of the homeless population: families receiving disability benefits, families that had active child welfare cases, families entering the work force, families who needed only a few months of assistance, and families in domestic violence shelters. Work Advantage, the program designed for working families, was the most direct replacement for HSP.

The City paid landlords directly for apartments leased by Work Advantage families; the families in turn paid a symbolic $50 per month. Work Advantage was a one-year program that could be extended for a second year if families met work and savings eligibility requirements, at the end of the second year families were expected to be self-sufficient.

Advantage

In August 2010, the Advantage program was altered. All of the programs save one were eliminated, the rental contributions of recipients went from $50 per month to 30% of their gross monthly income, and it became more tenuous for families to sustain their subsidy for a second year. In order to receive a second year of benefits a family had to have one member working 35 hours per week, and if renewed, rental contributions rose to 40% of gross monthly income. By the City’s own estimation, the changes made to Advantage would lower the percentage of families eligible for a second year of subsidies from 80% to 60%.

The Revolving Door of New Programs

Some critics are less strident in their critique, though maybe no less frustrated. Chris Parque, the executive director of Homeless Services United, a coalition of homeless services providers, says that the constant programmatic churn of the last few years has been damaging to providers as well as clients.

“Every time we do that [end a housing program], it breaks trust,” she says, which is problematic both for the provider-client relationship and the City’s relationships with landlords who have agreed to house shelter residents. “It creates even further barriers to landlords wanting to rent to low-income people.”

And every time the administration introduces a new program, “the slate is wiped clean,” she says. Little has been learned about the reasons why clients succeeded or failed while receiving HSP, Advantage NY, or Advantage subsidies. “We know that HSP and Advantage clients are returning [to shelter] in large numbers, but no one has evaluated these people to see why—specifically—they returned,” Parque says.

Parque argues that homelessness will only be dealt with if the city crafts a flexible plan, informed by the input of all major stakeholders. “We need as diverse a solution as we have people in the system,” Parque says.

Asked what will happen now that Advantage has ended, she says, “I think nobody knows.”

As frustrating as that uncertainty is for providers and advocates, it is doubly so for clients who had been counting on Advantage.

“I got a letter in the mail in March saying that Advantage was cut and they weren’t gonna pay our rent anymore … yada, yada, yada,” Natalie Rizzo, 31, says. “Then I got a letter saying they were gonna cover April, and nothing since.”

The mother of an 11-year-old, Rizzo is a full-time student at Borough of Manhattan Community College and a part-time employee of her church. She had been on Advantage for almost a year when she received the notice from DHS. Of the families who receive Advantage, 37% reapply for shelter after losing their subsidies, but for Rizzo, a short-term subsidy might have been all the help she needed.

“I had a plan, you know, they were going to cover my rent for two years,” she says. She is two semesters away from a teaching credential, but says she will have to drop out of school if Judge Gische allows the City to end her subsidy. Even if the subsidy continues for current recipients, knowing that the administration went to court to avoid paying has soured Rizzo’s outlook.

The city, she says, has become inhospitable for anyone just trying to get by.

The city, she says, has become inhospitable for anyone just trying to get by.

To cover rent on her $962-per-month Lower East Side studio apartment, Rizzo estimates she would need to earn $35,000 per year before taxes.

“You tell me what job is paying 35 right now?” she asks, and estimates that, given the economy and her work history, she would need to work two jobs in order to survive.

“My only other option would be to leave New York. And let’s just say it, that’s what Bloomberg wants. He wants a city for the rich,” she says.

“You can print that, put it in bold.”

Resources

The Legal Aid Society; www.legal-aid.org ■ New York City Department of Homeless Services; www.nyc.gov/dhs ■ New York City Council Committee on General Welfare; www.council.nyc.gov ■ New York City Housing Authority; www.nyc.gov/nycha ■ Nazareth Housing; www.nazarethhousingnyc.org ■ Theresa’s Haven; 718.299.6660 ■ The Coalition For the Homeless; www.coalitionforthehomeless.org ■ Homeless Services United; www.hsunited.org.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

Filling the Gap: Volunteers Provide Support and “Extras” for Homeless Families

by Carol Ward

Anne Moniz’s arrival at her day job as a state regulator for child care centers is rarely anticipated eagerly, nor is she joyfully welcomed as she walks through the door. But one evening a week, she gets the kind of greeting that makes her heart soar.

Moniz is a volunteer for Horizons for Homeless Children, a Roxbury, Massachusetts-based group devoted to providing play opportunities to homeless preschool children. She derives much satisfaction from knowing that she is making a difference.

A volunteer for Horizons for Homeless Children interacts with a toddler at a family homeless shelter Playspace program. Horizons recruits, trains, and assigns volunteers to Playspaces to supervise and encourage the children in educational play.

“I visit child care centers for licensing,” she says. “I have an okay reputation and I have lovely people that I deal with, but I’m not their favorite person to see walk in the door. But when we walk in the door at Harbor House,” she says, referring to the shelter in which she volunteers for the Horizons program, “we hear bellowing throughout the hallways: ‘It’s playgroup!’ or ‘They’re here.’ It’s like we have a fan club there. It’s just wonderful!”

Monica Aguirre, a volunteer at Center for the Homeless in South Bend, Indiana, has found a sense of community in her three years at the facility. Her role ranges from helping with toddlers to teaching adult-education classes, and everything in between. “It’s one of the most rewarding experiences I’ve ever had,” she says. “I love the community here, not only the guests but the staff and all that they’re doing.”

Aguirre and Moniz, and thousands of others nationwide, are part of a huge network of volunteers who help provide the myriad services needed to assist homeless families in finding permanent housing, from child care help to adult educational services.

Offering the Extras

Most groups that serve homeless families say much of what they are able to provide just would not be possible without the help of volunteers. Christine Achre, CEO of Chicago’s Primo Center for Women and Children, says her group is “able to offer far more” because of the work of volunteers.

“We have volunteers do everything from working with families to serving holiday meals to organizing book drives,” Achre adds. “Despite being a small organization we have between 100 and 150 volunteers who support us in one way or another.”

A youth volunteer at Thirteen Salmon Family Center, a day shelter run by Portland Homeless Family Solutions, reads a story to the children before naptime. The day center offers families staying in nearby shelters with daytime services and activities like enrichment programs for children, adult education classes, and meetings with housing specialists.

Margaret Menghini, program associate for New York’s Homes for the Homeless, has a variety of opportunities for volunteers, ranging from one-day commitments for students to long-term partnerships with specialists in individual fields. For example, volunteers have offered dental-hygiene workshops and HIV-awareness programs, a “coffee club” for mothers of small children, and many child-centric activities.

“As part of our services to our residents we always have day-care,” Menghini says. “But to do special activities—a special arts-and-crafts activity, for example—we wouldn’t be able to do that without volunteers.”

Many service organizations ask for a commitment—usually several months—for their core group of volunteers. Those individuals can offer support in certain areas like day care or literacy, or they might be specialists who can provide expertise. They are expected to show up consistently and often form relationships with the shelter residents. There are also numerous opportunities available on a more flexible schedule. Those include volunteer opportunities during the holidays or on field trips, or perhaps individuals or groups focused on specific one-off projects.

Menghini says her group takes advantage of the trend toward increased volunteerism among youth. “We see a lot of volunteers, usually starting at around age 10 or 11, through middle school, high school, and college,” she says. These are usually one-off or short-term commitments, many times performed in conjunction with a school project or service-learning requirement.

Volunteers, both temporary and permanent, are crucial to “keeping the mission alive” at Center for the Homeless, says Executive Director Steve Camilleri. In the month of March, the Center had 788 volunteers sign in, with “probably 250 distinct people” volunteering throughout the month. Some are there for just an hour or two, others commit to weekly or more often. Then there are some, such as “alternative spring break” groups, that arrive en masse and stay for a long weekend or a week to take on a major project.

Transition House in Santa Barbara, California, gets a mix of temporary and long-term volunteers, Executive Director Kathleen Baushke says. About 40 churches provide food and other support seven nights a week on a rotating basis. Longer term volunteers help with everything ranging from office work to infant care, while temporary or new volunteers typically take on cleaning or organizing efforts.

And sometimes a volunteer’s most crucial role is to simply let those in crisis know that somebody cares. Brandi Tuck, executive director of Portland Homeless Family Solutions, which relies on a network of about 500 volunteers, says that the newly homeless in particular need that support.

“The number of homeless families has increased dramatically,” Tuck says. “We’ve been seeing a lot of journeymen, carpenters and painters, union workers—people who were making good money before. It’s so hard for them and their families, but we have regular volunteers who talk to them, really get to know them, and that helps.”

Marilyn Chrzan has experienced that firsthand. A formerly homeless “guest” at South Bend’s Center for the Homeless and a recovering alcoholic, Chrzan says volunteers offer a crucial connection. “When I was a guest, dealing with volunteers was always a positive experience even if it was only as a connection to the outside world,” and with someone who could talk about simple pleasures like movies or restaurants, she says.

Chrzan adds that given the overwhelming plight of being homeless, “sometimes you just want to talk to somebody. There’s not always a staff person available so it’s good to have a volunteer who can at least listen to what you have to say.” Chrzan, who lives in transitional housing, is now a volunteer for the group. She admits that she was “initially dragged into” that position. “Now I look forward to coming because I feel I’m giving back,” she adds.

Motivations and Boundaries

There is no typical volunteer; they are a diverse group who are motivated by a broad range of reasons. Mary Solomita, another Horizons for Homeless Children volunteer, responded to a radio ad from the group about 15 years ago, and she has given a couple of hours a week since then.

“I’d never really heard about homeless children,” she says of her response to the ad. “It tugged at my heart. I signed up for the training and agreed to a six-month commitment, and now, 15 years later, I’m still there.” Solomita, an educational psychologist in public schools, has recruited family and friends to help, either through volunteering or raising funds to help Horizons and individual shelters.

Monica Aguirre, a volunteer at the Center for the Homeless, attends a volunteer training to better meet the needs of the homeless children and families she interacts with each week.

Megana Ballal is newer to the world of volunteering. She has been an AmeriCorps volunteer for the New York Children’s Health Project since September. A month or two into her commitment, she decided she wanted more. Ballal began volunteering at Prospect Family Inn, a shelter in the Bronx run by Homes for the Homeless.

Ballal plans to enter medical school in the fall, and says the AmeriCorps position has boosted her interest in family health, while the Prospect Family Inn has awakened an interest in pediatrics. “I’ve learned a lot about just how much kids living in this type of setting have to deal with,” she says. “I feel like I’ll definitely use that in my profession going forward.”

Particularly for the long-term volunteers, dealing with a vulnerable population—especially a population that includes children—can challenge their emotional equanimity. Because the shelter system requires that families and children transition quickly and often without warning, volunteers have to be compassionate and somewhat detached at the same time.

“I’ve definitely seen people come and go,” says Aguirre. “It can be heart-wrenching at times.”

Moniz says that after getting attached to children in her early months of volunteering, she now is able to view departures in a positive light. “I try to keep it in perspective but it’s hard because we don’t get to say goodbye most of the time,” she says. “These are kids who we really get to know, and who know us. But I just know there’s going to be another child waiting there who needs the support.”

Sarah Fujiwara, chief Playspace Programs officer for Horizons for Homeless Children, says she advises volunteers to view departures positively, because families are moving on to more permanent housing. “We try to prepare the volunteers that there will be turnover among the shelter families, and explain the important role they are doing by being consistent and telling the kids, ‘See you next time,’ without making any elaborate promises,” she says. “We’re there to help the child and the family start to build some new memories.”

Recruitment and Retention

There are thousands of volunteers working with homeless children and families across the country. While service organizations are always searching for new ways to attract volunteers, on a national scale that may be a bit easier these days. The recession caused the number of homeless families to rise, but it also spurred an increase in volunteering, according to Washington, D.C.-based Corporation for National and Community Service (CNCS).

In a report entitled “Volunteering In America 2010,” CNCS found that approximately 1.6 million more volunteers served in 2009 than in 2008. The volunteering rate increased in 2009 to 26.8 percent, up from 26.4 percent in 2008. “Americans have responded to tough economic times by volunteering in big numbers,” Patrick Corvington, CEO of CNCS said at the release of the study last summer. Previous research would suggest that volunteering should drop during an economic downturn, because volunteer rates are higher among jobholders and homeowners, he said. Instead, volunteering increased at the fastest rate in six years, and the volunteer rate went up among all races and ethnic groups.

Tuck says she is seeing that trend firsthand. “We seem to be increasing our number of volunteers every year,” she says. Many are spurred by compassion for the growing needs of the community, others simply have more time and motivation than before. “A lot of people may be out of work and turning to volunteering to improve their resumes,” Tuck adds. “They also realize that by volunteering first, it could be a great way to get hired.” Tuck herself was a volunteer before working her way up to director, and she has hired several volunteers over the years as well.

Camilleri started as a volunteer at Center for the Homeless, and says many of his staff did as well. Competition for jobs in all fields is fierce, he notes, and people see volunteering as a way to enhance their resumes.

Still, service providers exert quite a bit of effort to drum up community support. Dr. Peter Lombardo, director of community involvement at Center for the Homeless, says outreach is constant. “We grab every opportunity we can to speak to people—rotary clubs, churches, high schools and colleges, and even Sunday-school classes,” he says. “Those opportunities lead to a lot of volunteers in addition to the regular ones who seek us out.”

After attracting a volunteer, many service providers say they spend considerable time training the individual and making sure they effectively match a volunteer to a role. Jett Black, coordinator of volunteer services and children’s programs at Transition House, says time spent on the front end can create a happy and committed roster of volunteers, while at the same time maximizing a program’s potential. “We try to match volunteers with their talents—discovered through interviews and training—as much as by their availability,” she says. “For example, they might come in thinking they want to help with children, but we find they’d be more effective on data management. Time on the front end more than pays off on the back end.” ■

Seven Tips for Creating Powerful Volunteer Programs

Volunteers are crucial to the success of any service program, but attracting, managing, and keeping those volunteers can be a daunting task. Here, service providers offer tips on creating and sustaining a flourishing volunteer program.

1. Use current volunteers as assets in attracting new volunteers. Volunteers who feel needed or appreciated will tell others, laying the groundwork for future volunteer contacts.

—Jett Black, coordinator of volunteer services and children’s programs, Transition House

2. Seize every opportunity to tell your organization’s story in your community. Those opportunities often translate into new volunteers.

—Peter Lombardo, director of community involvement, Center for the Homeless

3. Ensure volunteers are well trained before they interact with residents. Relay specific expectations and reinforce them.

—Brandi Tuck, executive director, Portland Homeless Family Solutions

4. Make sure each volunteer has a defined job description. This helps volunteers to be more effective and confident in their service as well as prevent confusion and redundancy.

—J. Black, Transition House

5. Have activity ideas on hand. Volunteers can sometimes be at a loss for how to contribute or interact. Having some activities on hand for the various age groups you serve helps spark ideas.

—Margaret Menghini, program associate, Homes for the Homeless

6. Thank your volunteers. Constantly. Make a point to say “thank you” at the time of their service.

—J. Black, Transition House

7. Use an online volunteer scheduling tool like Volgistics. The benefits reaped make the program worth its cost.

—B. Tuck, Portland Homeless Family Solutions

Resources

Horizons for Homeless Children; www.horizonsforhomelesschildren.org ■ Center for the Homeless; www.cfh.net ■ Primo Center for Women and Children; www.primocenter.org ■ Homes for the Homeless; www.hfhnyc.org ■ Portland Homeless Family Solutions; www.pdxhfs.org ■ Transition House; www.transitionhouse.com.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

The Historical Perspective—

Lunchtime: How the School Lunch Program Began

by Ethan G. Sribnick and Rebecca Amato

The breakfast and lunch programs in public schools have become the subject of heightened political debate. On one side, high-profile advocates such as Michelle Obama have called for higher nutritional standards. “We owe it to the children who aren’t reaching their potential because they’re not getting the nutrition they need during the day,” argues the first lady. On the opposing side, former Alaska governor Sarah Palin has complained that restricted school lunch menus are another example of the “nanny state run amok,” an excessive intervention into how parents raise their children. Though this debate continues to make headlines, the issues at stake are not new. In New York City, the effort to provide relief for childhood hunger and questions over how best to feed undernourished children go back well over 100 years.

Throughout the nineteenth century in New York, child hunger was inseparable from the larger problems of urban poverty. Both private charities and the city government provided food assistance to the poor as part of broader relief programs, often in the form of temporary grants for food and fuel. On the rare occasions that food was provided on a standalone basis, it was often through government-sponsored soup kitchens, like one constructed with money from the New York City Common Council in 1806. When relief was targeted specifically at hungry and malnourished children, it was administered through the family. Child care, most reformers thought, should be under the purview of parents. Since it is the “responsibility of the family” to meet “the personal needs of children,” wrote Edward T. Devine, head of New York’s Charity Organization Society, most people “prefer to see the relief of children remain an integral part of the general relief system,” which focused on family-based, rather than individual support.

In keeping with the goal of providing highly nutritious meals, cafeteria workers were often professionally trained in the field of home economics. Here, two workers dressed in uniforms serve a group of schoolchildren. Courtesy of the National Library of Medicine.