Publisher’s Note

Dear Reader,

Welcome to the Summer 2016 issue of UNCENSORED. This issue takes a close look at both services and policies to understand where they do, can, or might have an impact on family homelessness.

Our first feature, “Working Together,” shares how a routine class assignment for a group of West Point cadets developed into a greater understanding of family homelessness while providing much-needed mentoring to a group of children in a New York City shelter. Our second feature, “In the Trenches,” examines rapid re-housing where the rubber hits the road, recounting experiences in cities and communities across the nation and taking a closer look where it works and where it does not. Our third feature, “A Better Life for the Whole Family,” explores the much talked about “two-generation approach” through the work of a Little Rock, AR, shelter that is addressing the needs of the whole family.

The topic of this issue’s National Perspective is last year’s reauthorization of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act now known as the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) as it pertains to improving the education of homeless students. In our Guest Voices essay, “Are We Creating Chronic Homelessness?,” Barbara Duffield, director of policy and programs for the National Association for the Education of Homeless Children and Youth (NAEHCY), reexamines the assumptions of current federal homelessness policy, its emphasis on chronically homeless individuals, and its impact on homeless families.

We trust this issue of UNCENSORED will give you much food for thought. We welcome your comments at info@ICPHusa.org or on social media.

Sincerely,

Ralph da Costa Nunez, PhD, Publisher

President and CEO, Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

Working Together: How a Class Project Became Much More

by Katie Linek

Located on a mountainside in New York State with beautiful views of the Hudson River, the United States Military Academy, also known as West Point, is a four-year federal academy for undergraduate studies and military training. Students there, known as cadets, receive a free, world-class education, which focuses on the development of leadership skills in the academic, military, and physical arenas. Upon graduation, the cadets are commissioned as second lieutenants in the Army.

Cadet Zachary Cothen was the liaison between the cadets and Homes for the Homeless. He found and researched the organization, helped with the planning, and attended each event.

More than 60 miles to the south in the New York City borough of Queens, just on the outskirts of the John F. Kennedy International Airport, is the Saratoga Family Inn, a Community Residential Resource Center (CRRC) serving 255 families with approximately 375 children. CRRCs combine the basic services of a traditional homeless shelter with programs for families living in both the shelter and the surrounding community.

Although these settings and their residents may appear worlds apart, one class assignment changed the lives and perspectives of all involved.

It Began with a Class

The Academy is very selective; less than one in 14 applicants is admitted each year. Candidates must be between 17 and 23 years old, have above average high school and/or previous college grades, perform strongly on standardized testing, provide written essays and letters of recommendation, receive a nomination (usually from a member of Congress), submit to a formal interview, and undergo a Candidate Fitness Assessment and a complete physical exam.

“The top 30-40 cadets at West Point go through a two semester sequence the second semester their junior year and first semester their senior year,” says Major Benjamin Summers, an instructor at West Point, explaining the United States Military Academy Graduate Scholarship Program that he and another instructor run. The program is an intensive mentorship program that prepares cadets to compete for graduate scholarships.

The most recent course the cadets took, Critical Thought, helps the cadets become better leaders, officers, scholars, and citizens. “Their focus this semester was inward and understanding more about themselves, and then also understanding how to look at the world in a more nuanced way. They learned how to look at issues through a critical thinking lens,” explains Summers.

In the class, students were divided into “leadership development groups.” Cadets Zachary Cohen, Chong (CJ) Na, Shelby Lindsay, Nathanael Thomas, and Araceli Sandoval formed one such group.

“On our first day of class we were told, ‘I do not care what you do or how you do it—give back to the community in some way and tell me how it goes on the last day of class,’” describes Cohen, one of the cadets. “That was the assignment. It was open-ended with nothing else to it—no other instructions. We have never really done anything like it before and we were excited to get started.”

“Service to the community helps instill a little dose of humility and appreciation for what others are doing for their communities and what others are doing that falls into the category of service,” proposes Summers. “It forms connections and helps share perspectives that are meaningful for both parties.”

“The skills that our group possesses are people skills,” Lindsay, another cadet, suggests. “We all really enjoy working with children, so we tried to focus our efforts on something along those lines.”

Filling a Need

Each summer, Homes for the Homeless (HFH) Summer Camps sends more than 500 homeless and formerly homeless children from New York City to sleepaway camp in the woods of Harriman State Park. Most have grown up in the city and have not spent much time in the wilderness. Attending camp offers them the opportunity to have fun, make new friends, and learn new skills like swimming—all away from the stresses of everyday life. HFH Summer Camps is run by Homes for the Homeless, the non-profit organization that operates the Saratoga Family Inn.

“When you go up to the camps while in session and see the kids in action and how rewarding it is … these kids really take a lot away from it,” says Cara Pace, vice president for planning and operations at Homes for the Homeless.

The camps are only in session during the summer months, therefore every spring HFH seeks out volunteers to assist in an exhaustive cleanup of the debris that gathered during the winter months. “It is brutal, hard, hot work with bugs,” says Pace. “It involves clearing out the leaves and picking up the ‘winter’ from the campsites.” In her search for dedicated volunteers, Pace contacted the volunteer coordinator at West Point.

At around the same time, the cadets were looking for an opportunity to help the community. “I was asking about opportunities in New York City and asking about different organizations that might be looking for help. Someone referred me to Cara,” tells Cohen. Lindsay adds, “We asked Cara, ‘What can we do? How can we make an impact?’”

‘A Day in the Life’

One Saturday in April, a group of 13 kids from the Saratoga Family Inn travelled with their chaperones up the Hudson River to West Point to experience a day in the life of a West Point cadet. The day began at the lowest part of the campus for a hike up the mountainside. Cadets Cohen and Na led and got to know the group. “The kids saw West Point and they spoke to CJ (Cadet Na) and Zach about what it takes to get there,” recollects Roy Anderson, director of recreation at the Saratoga. “The cadets were articulate when explaining they have to do well in school.”

For lunch, the group ate in the cadets’ mess hall—a site not accessible to the public. “They learned what a plebe is (a first year cadet) and what they go through—how they have to sit at the table, how they should not waste food, how to properly use their utensils, what is the appropriate tone of voice to use at the table,” recalls Pace when discussing the experience.

While youth from the Saratoga Family Inn left their day at West Point feeling inspired, the cadets were grateful to spend the day making an impact on young lives.

After lunch, the group was in for a special treat. “I have some friends on the football team and I asked them, ‘What are you guys doing? Will you come play football with some kids?’ And they were all about it,” says Lindsay. “I had asked three people and it turns out that there were over ten of them there.”

“We met quite a few football players,” says Anderson. “There were so many football players that actually turned up on their own to meet the kids that they had a pickup football game.”

The kids had the experience of a lifetime, playing football with a group of Army Black Knights (West Point’s football team) in Michie Stadium, a 38,000-seat football stadium on the West Point campus.

The youth and football players formed a bond that day. “A lot of the players actually came from similar situations as our kids—very poor backgrounds, formerly homeless, from Queens close to where the Saratoga is—and the kids really got to connect with them,” says Pace. “It was a very natural bonding experience; it was really wonderful to see.”

“One of the older kids, Julius, he is usually very quiet,” says Anderson. “He is from Florida as is one of the cadets, and that connection helped him to open up. When we played football, Julius’ favorite sport, he looked pretty good! He looked right at home playing football with these college students.”

“In an unexpected turn of events, we found out our football team was having a spring football game at West Point,” says Cohen. The group took a second trip up to West Point to attend the Annual Black and Gold Spring Game in the stadium where they had played just a few weeks prior. They cheered especially loud for their new friends. “After the game, I asked all of the football players who were there for the pickup game to stay and sign autographs for the kids,” continues Cohen.

When the football season starts, Anderson plans to watch the games as part of the recreation program so that the group can continue cheering on their favorite team.

Battle of the Board Games

The second part of the project entailed a few of the cadets making the trip down to the Saratoga to spend some additional time with their new friends.

“We set up a board game tournament at the Saratoga so that they could tour what a shelter is like, experience our recreation program, and interact with the parents,” explains Pace. “They treated us to lunch up at West Point, so the kids hosted them at a very nice luncheon afterwards.”

Players on West Point’s football team bonded with the children from the Saratoga, and invited them to attend their Annual Black and Gold Spring Game where they took the time to sign autographs for the group.

More than 40 children and some parents gathered in the recreation room at the Saratoga to play games like Connect 4, Stratego, Uno, Battleship, and life-sized Jenga with the cadets, who wore their Army White Uniform, one of the Army’s dress uniforms. “That was super impressive to the kids,” says Pace.

Not only did the friendships that formed on the hike continue to grow even further over the course of the day, but having the cadets on their ‘home turf’ was meaningful for the youngsters. Living in a shelter, they are not able to have friends over to play. However, this experience offered them a fun, stress-free chance to enjoy childhood.

“CJ and I and a couple of the kids were playing life-size Jenga,” says Cohen. “There were kids all around us and it was hilarious. It was very normal. To see how happy those kids were just to be interacting with people and each other … it was cool. It was a little, simple thing, but how hard we were all laughing together was awesome and very memorable.”

Playing games and having fun with the cadets offered a different dynamic than when the group went up to West Point. The day of fun helped the children to see the cadets as regular people with whom they could identify and look up to. “They are meeting young cadets who are future leaders, and they are saying ‘You can be that too,’” says Anderson. “A lot of parents were also very interested and began to think ‘Maybe my kids can do this.’”

Camp Cleanup

For the final part of the project, ten cadets travelled to HFH camps on a rainy Sunday to help clean it up for summer.

“We satisfied the project needs for volunteering in the community and working as a mentor with underserved kids, but we also needed volunteers to clean up at camp,” says Pace. The group was more than willing to assist.

The group raked and moved leaves, filling an entire dumpster with debris. The physically fit group proved to be an ideal pool of volunteers who played an essential role in providing homeless youth with an amazing summer camp experience.

As Major Summers explains, the importance of having West Point cadets participate in acts of service, such as helping to clean up winter debris at Homes for the Homeless Summer Camps, is to help form connections and share perspectives that are meaningful for everyone involved.

Learning about Family Homelessness

In addition to the various projects that the cadets planned and participated in, HFH offered the cadets an additional opportunity to learn more about family homelessness. HFH president Dr. Ralph da Costa Nunez travelled to West Point to serve as the final guest lecturer in a series of lectures and workshops for the cadets’ class. Dr. Nunez has dedicated his life to working on behalf of homeless families. He has done so for more than 30 years at the city and state levels of government and in the non-profit sector.

“He provided a lecture to them on the history of homelessness in New York City, the challenges faced in the operation of shelters, and what it is like to make a difference with public policy around the subject of homelessness,” explains Pace.

“Dr. Nunez coming up gave us a chance to look at a really important issue in society,” says Summers. “It tied together a lot of what we try to extract from the cadets throughout the semester. ‘What are you passionate about in life? What are the issues that mean the most to you? What is a way to think about those issues through a nuanced, critical thinking lens? And what are you going to do about it? How are you going to put forth effort to tackle that issue?’ It was cool for the cadets to see someone who has dedicated their life to an issue.”

The Power of a Positive Influence

In all, the service project provided a valuable experience for both the kids and the cadets.

Children living in poverty have a higher risk of developing a variety of social, emotional, and behavioral problems, however, the development of positive relationships can help to offset this impact. The importance of role models in the lives of these children cannot be overstated. They look to role models as an example of who they can be and role models help shape how they behave in school and relationships.

Living in a shelter, the kids are not able to have a traditional playdate where they can invite friends over. The visit from the West Point cadets for the Battle of the Board Games, however, offered the kids at the Saratoga a fun and stress-free day.

“The cadets are excellent role models—they see things through,” says Pace. “They are extremely respectful and polite, have strong integrity, incredible listening skills, and they are very purposeful in what they are doing. The quality of their character is very impressive. I think the academy does a tremendous job; we benefited greatly from the training they provide to the cadets because our kids get to be around remarkable young adults.”

“It makes an impact for the kids to have someone to look up to and to encourage them—especially someone who is not too far off in age from them,” says Lindsay. “Apparently when there are older adults the kids sometimes do not identify as easily with them, but they find that the kids respond more to interactions with younger volunteers.”

“The impact of such strong role models is immense,” added Anderson. “The kids got to have more positivity around them. The more positive influences they have surrounding them, the better.”

Even the parents recognized the important role the cadets were playing in the lives of their children. One of the moms approached Cohen to thank him for taking the time to be a positive influence in her child’s life and emphasizing how important an older brother or father figure can be. “In my life, my dad was one of the biggest influences that got me where I am today, so when the mom approached me and said, ‘The fact that you guys are here to be that older brother figure, even for an hour, a day, or a weekend or two, it means that much more to them. They need that in their lives more than they need a new pair of shoes,’ … that was very meaningful.”

The most important lesson the group learned from the cadets, however, was that college and success is within their reach if they apply themselves.

“College should be part of the plan for the children here and it is often not,” explains Anderson. “They are just trying to get out of middle school. They are not thinking along the lines of planning for their future because they understandably have other more pressing issues. We are planting the seed now that college is part of the plan.”

“The kids were inspired to see something long-term for themselves. That they could go on to higher education, that there are opportunities out there, that you can get a great education subsidized if you apply yourself and have really good grades and do community service,” added Pace. “They could end up being a West Point cadet themselves. It helped them see their future is in their grasp—that they can cultivate where they want to go.”

In fact, many of them were encouraged by their interactions with the cadets. “The kids wanted to move in with the cadets—to be their roommates,” recalls Pace.

One young boy, Giovanni, was very clearly in his element around the cadets. Although the trip to West Point was organized for the older participants of the Saratoga recreation program, he was so persistent that they allowed him to attend. He ended up leading the hike alongside the cadets. “It definitely sparked something for him,” suggests Pace. “I see this connection and I believe that he will jump at any opportunity to do these types of activities. If this one boy is inspired to do well academically and to follow his dreams, this is worthwhile.”

Developing a Passion

The cadets were also inspired and learned a lot from their time with the boys and girls. “It has been such a blessing to us to be able to interact with and learn from them,” says Lindsay. “We realize that we are given a ton of opportunities at West Point and I think it is always good to remember that we have those opportunities and that we need to consider people who may not have so much right at their fingertips.”

“While I am sure there were many benefits from the children’s perspective, there was also a huge benefit from the cadets’ perspectives,” says Summers. “They saw the struggles that others go through and felt the amount of appreciation that a child can show toward you in the five hours you spend with them throughout the day.”

“I think they developed a passion they did not even know they had,” continued Summers. “The cadets were grateful to have that experience with the children. I do not think they saw it as putting themselves out there; they saw it as being on the receiving end of something really special.”

“They were very focused on making it a rewarding opportunity for our children and I commend them for their dedication to the project,” says Pace.

The cadets emphasized that although the class sparked the project, this experience was much more than an assignment to them. They plan on continuing their work with the community and with Homes for the Homeless.

At the Academy, each cadet holds a position within his or her company (a group of about 120 cadets of all different class years). Inspired by the work with Homes for the Homeless over the past few months, Lindsay requested to be Community Service Officer for her company. “I will have the opportunity to encourage and provide ways for my company to get involved,” she says. “The relationship that we have established with Homes for the Homeless will hopefully provide an opportunity for me to encourage more of my classmates to get involved in that.”

“When you are doing something for someone else, it can ignite passions that you did not know you had,” says Summers. “When those passions surface, that can be an enlightening moment where you think ‘Now I realize this is something that makes me tick. This is something I really care about and I would like to think about more or study more or dedicate part of my life to.’”

Resources

United States Military Academy West Point www.westpoint.edu/SitePages/Home.aspx West Point, NY ■ Homes for the Homeless www.hfhnyc.org New York, NY ■ Homes for the Homeless Summer Camps www.hfhcamps.org New York, NY.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

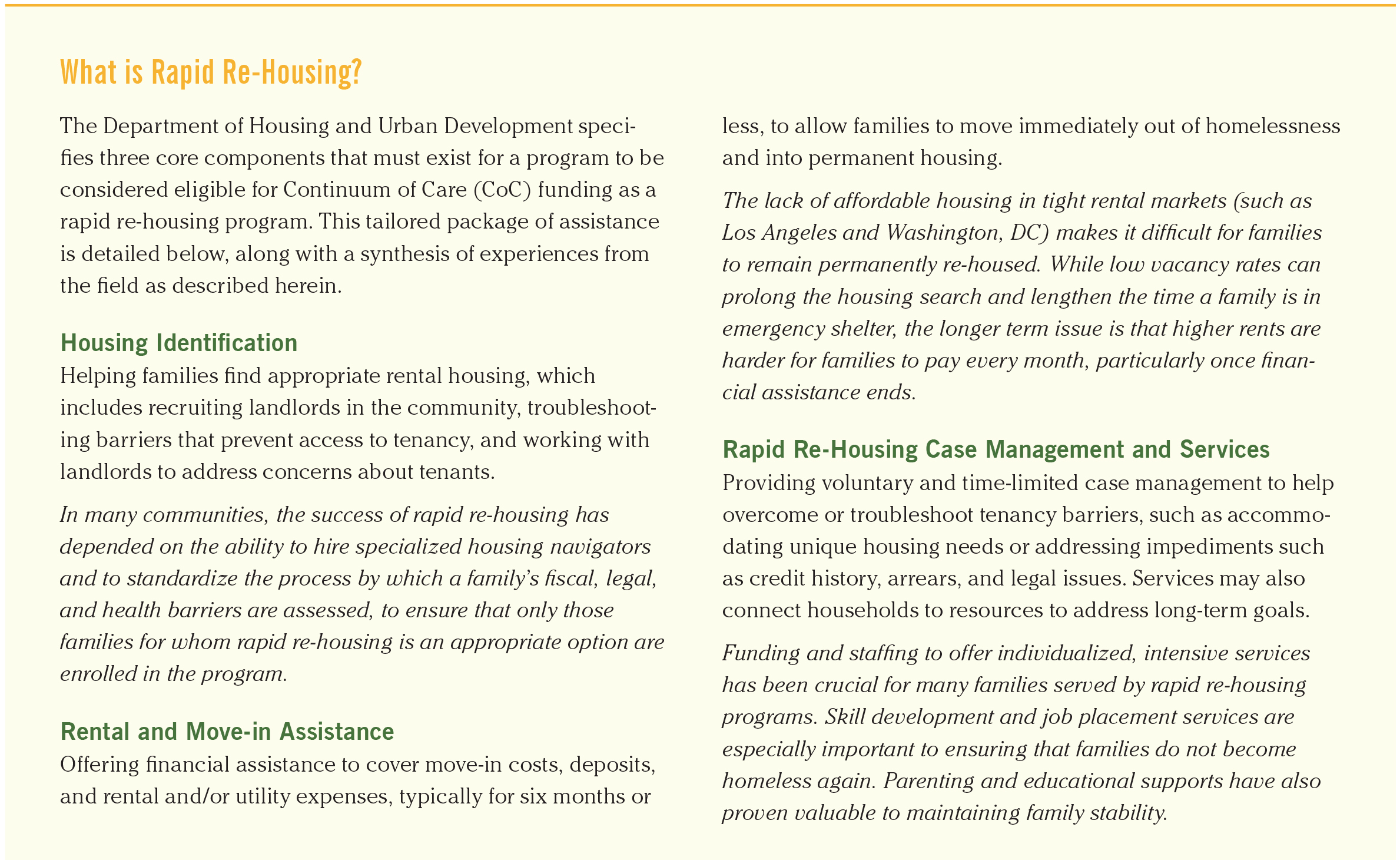

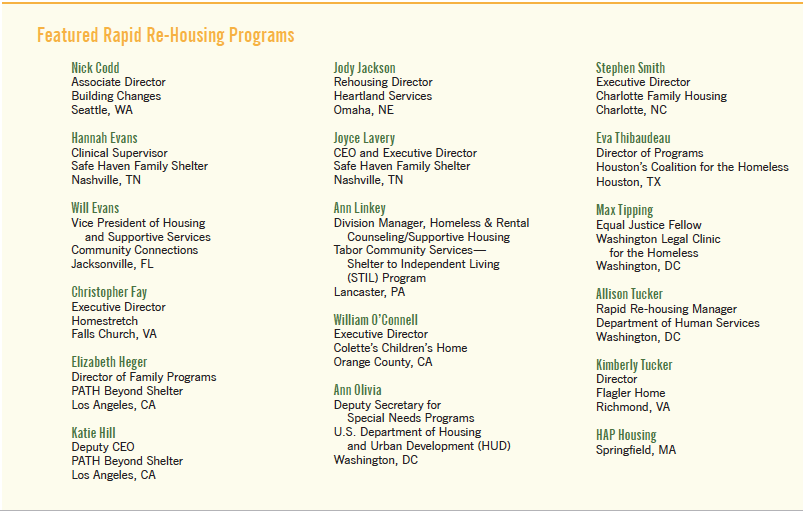

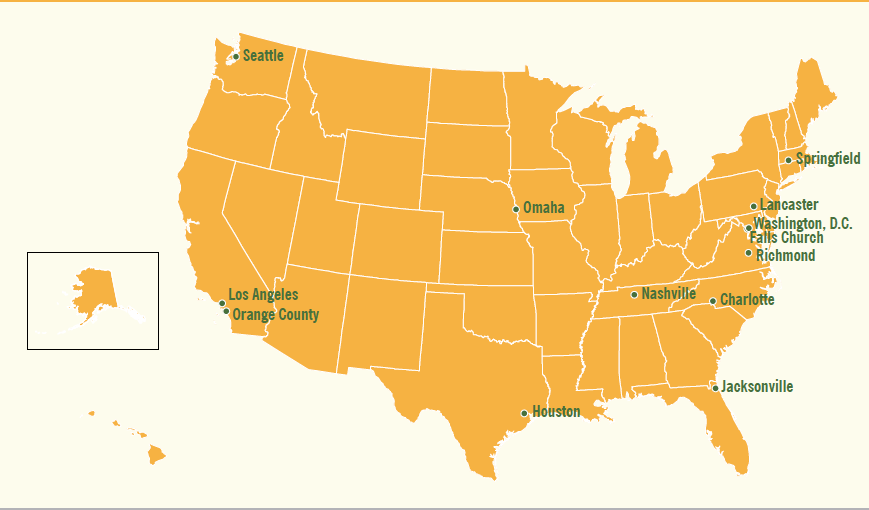

In the Trenches: How Communities Are Faring in the Era of Rapid Re-Housing

by Robin D. Schatz

with additional reporting by Linda Bazerjian

The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) has shifted its funding priority toward rapid re-housing, its chosen intervention for tackling the homelessness crisis. As HUD continues to study the effectiveness of rapid re-housing strategies through its Family Options Study, UNCENSORED wants to give a voice to those on the front lines who are navigating this transition. While the jury is still out on rapid re-housing, the experiences of service providers raise important questions about what is needed to permanently end a family’s homelessness.

In 2007, when Kimberly Tucker became director of the Flagler Home, a transitional family shelter just outside of Richmond, VA, she found herself in charge of a much beloved community institution in this historic, Southern city of about 220,000 people on the East Coast.

“We often get into our camps as if there is one option that would work for everyone. We know that is not true. With every population, we are trying to build up choices.”

—Eva Thibaudeau, Director of Programs,

Houston’s Coalition for the Homeless

Flagler Home was founded in 1989 by St. Joseph’s Villa, a large private nonsectarian multi-service agency, to provide transitional housing and support services for homeless mothers and their children. As Tucker describes it, they offered “all kinds of life skills and workshops and training and support to be able to not just help resolve their homelessness, but to hopefully never become homeless again, and for people to become self-sufficient when they get out.”

Little did Tucker know that six years later, she would recommend Flagler’s closure to her parent organization, rewriting all the job descriptions and making her entire staff reapply for their positions, as they shifted to rapid re-housing.

Growth of Rapid Re-Housing

Fueled by a wave of federal funding from HUD, communities from coast to coast have implemented rapid re-housing programs—sometimes with enthusiasm, and at other times with trepidation.*

Rapid re-housing aims to help families exit homelessness and return to permanent housing, ideally within 30 days of entering a shelter. Programs generally provide short-term subsidies, case management, and an array of support services, for anywhere from four months up to a year or longer, depending on the community. Unlike transitional programs, which may place conditions or restrictions on families for participation, rapid re-housing does not require sobriety, employment, or other conditions for eligibility.

Rapid re-housing for homeless families is not a new concept. Beyond Shelter in Los Angeles began using the approach in 1984 (the organization has since merged with the larger nonprofit PATH). In Lancaster, PA, a small city of about 55,000 in its urban center, and a metro-area of about half a million, the Shelter to Independent Living (STIL) program has been operating since 1992 and was cited in a case study by HUD on successful models for rapid re-housing.

HUD made its first foray into rapid re-housing in 2007, when Congress appropriated $25 million for a demonstration project for families, later selecting 23 communities to participate. The idea, says Ann Oliva, deputy secretary for special needs programs at HUD, was to “build our knowledge,” to learn what rapid re-housing is and how it works with different types of families. In the study, HUD looked at how 500 families in the pilot fared a year after release from the program. Among other findings, the study showed that 76 percent of families moved at least once in the 12 months after leaving rapid re-housing, and ten percent of all households experienced an episode of homelessness in that period.

Two years later, as America reeled from the effects of the biggest economic downturn since the Great Depression, Congress passed the American Recovery and Investment Act of 2009, which President Barack Obama signed into law on February 17. Embedded in that bill was $1.5 billion for the Homelessness Prevention and Rapid Re-Housing Program, or HPRP.

“After families exit rapid re-housing they experience high rates of residential instability. Many move again or double up within a year and face challenges paying for rent and household necessities.”

—2015 Urban Institute report

Oliva says that the advent of HPRP marks the first time the agency tried out rapid re-housing at scale. “We were very young in our development of what good rapid re-housing as an effective project looked like,” she says. “We learned a lot through the course of three years. We actually ended homelessness for 1.3 million people.”

Later that year, Obama signed into law The Homeless Emergency Assistance and Rapid Transition to Housing Act, better known as HEARTH, which reauthorized the McKinney-Vento programs run by HUD and legitimized rapid housing as an effective model for reducing homelessness.

In 2013, HUD released a memorandum that endorsed the use of TANF (Temporary Assistance for Needy Families) funds to pay for rapid re-housing programs. The next year, in 2014, the Veterans Administration authorized funds for rapid re-housing for veterans and their families. That same year, the U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness issued its plan for ending family homeless by 2020, with rapid re-housing a cornerstone of the efforts to make homelessness a “rare and brief occurrence.”

For Fiscal Year 2014–15, HUD funded almost twice as many rapid re-housing projects as in the previous year, says Oliva. “For several years, we have really been pushing our communities to evaluate all of their projects and look at system performance and project level performance,” she says, acknowledging that there has been a “significant decline” in funding to transitional housing and supportive housing. “As national policy, we want to provide as much housing as we can through our program. We are the only federal agency that does housing.”

HUD also shifted 15 percent of its funds, or $355 million, into Tier 2 Continuum of Care, where communities competitively bid for funding and are scored according to a formula that gives more points to programs that emphasize rapid re-housing and permanent supportive housing, over transitional housing.

Last year, HUD released the interim findings of their Family Options Study, the largest experimental study ever conducted to test different interventions designed to address family homelessness. HUD has not yet released the full results of its three-year study which began in 2010; however, the interim findings based on the first 18 months comparing permanent housing subsidies, rapid re-housing, transitional housing, and the usual care at the local level are mixed and inconclusive.

Who Does Rapid Re-Housing Work For?

Critics say that families who are rapidly re-housed will wind up back on the street if the root causes of their problems are not addressed. Christopher Fay, who runs Homestretch, a coalition of churches and community people that support programs to end homelessness in the Falls Church, VA, suburb of Washington, DC, says the requirements Homestretch imposes on participants in its two-year transitional shelter program assure greater success. “Our theory is to take time with the family to equip them with skills and pay off their debt,” he explains. “You have to address poverty. We are ultimately saving people from lives of homelessness by driving them out of poverty.”

Proponents, on the other hand, say getting a roof over people’s heads is the priority and that ending poverty is a much bigger task for society to tackle, one that requires the resolve of policymakers and politicians and a commitment to creating more affordable housing. They say that a family traumatized by homelessness and thrust into the chaos of shelter life cannot focus on turning their lives around until they get housed.

“In Los Angeles, the vacancy rate is less than two percent and it is not uncommon to find homeless families living in their vehicles. Even when families get vouchers for Section 8 subsidized housing, it is often impossible to find them an apartment.”

—Katie Hill, Deputy CEO, PATH Beyond Shelter

In Tucker’s case, she realized that the majority of people leaving Flagler Home were not moving into permanent housing. “Oftentimes they were like, ‘I have had it with the rules’ and would move out in a huff.” People were also not getting jobs, for the most part, although she had an employment specialist and an on-site childcare facility. She tried everything: making the rules more relaxed, making them less relaxed. She tried morning meetings. But nothing seemed to be working.

In 2010, Tucker launched a small-scale, privately-funded pilot project to begin rapidly re-housing “low-barrier families”—those who only have a few factors that make it difficult to obtain housing. She converted one of their case managers into a housing specialist who began working directly with landlords to find housing for their clients. The results were encouraging: “We housed about 30 people, and they seemed to stay housed,” she says.

During this time, Tucker reduced the average length of stay, first from two years down to one, and then to six months. “We said we were pretty much a shelter with a housing focus,” she recalls. “When you walked in, you did not have a case manager anymore. You had a housing specialist to help you find housing, and you had an employment counselor who could help you find income.”

In June 2013, St. Joseph’s Villa closed Flagler for good and converted all their efforts to rapid re-housing. Tucker also says that, a year after leaving the rapid re-housing program, almost 100 percent of their clients have stayed out of homeless shelters.

More than 3,000 miles away in the Los Angeles suburb of Orange County, CA, William O’Connell, executive director of Colette’s Children’s Home, tells a different tale about serving homeless mothers and their children from the Southern California towns of Anaheim, Huntington Beach, Palencia, and Fountain Valley. Very few of the single-mother families who come through the doors of Colette’s Children’s Home are low-barrier.

“Rapid re-housing will work for high-functioning folks,” says O’Connell, as he explains that the majority of mothers seen by his nonprofit transitional shelter and permanent supportive housing provider have three or more “high-risk” issues like substance abuse, mental health issues, experienced domestic violence, have long unemployment histories, felony convictions, or lack of transportation.

“We often get into our camps as if there is one option that would work for everyone,” says Eva Thibaudeau, director of programs at Houston’s Coalition for the Homeless, the Continuum of Care lead agency for three municipalities in the greater Houston area. “We know that is not true. With every population, we are trying to build up choices.”

In Charlotte, NC, a metropolitan area that includes the city proper and the more suburban Mecklenburg County that Charlotte F amily Housing Executive Director Stephen Smith calls “up-and-coming with a lot of tech companies and rents that are starting to get higher,” the issue is not rapid re-housing vs. transitional shelter; it is sustaining vs. obtaining housing. Smith’s agency typically serves working families who are experiencing homelessness.

“We are struggling because HUD is using the chronic homeless playbook for families,” says Smith. “It works for single adults but not for the population of families we are serving.” He believes the problem is not that HUD is pushing rapid re-housing but rather that it is dictating that jurisdictions, and ultimately providers, must serve families with the most barriers first because that is what worked on the single adult side.

“Family homelessness is a complex issue,” Smith continues. “HUD thinks the way they did it with singles is the answer. If it were as simple as one solution for everyone, we would have fixed homelessness a long time ago.”

In Massachusetts, rapid re-housing did not work for the Rivera family—a two-parent household with four children served by HAP Housing, which operates a rapid re-housing program in Springfield, MA, a city of about 150,000 in Western New England. After getting placed in rapid re-housing after a few months in shelter, their stabilization case manager at HAP Housing soon discovered there were underlying mental health and substance abuse issues, and she had serious concerns about the welfare of the children.

“Knowing the barriers that the family has encountered in the past with being rapidly re-housed and the potential dangers that the children faced without supervision from agency staff, it is clear that this family needs a more supportive environment that will help meet their mental health, substance abuse, and child welfare needs,” according to information provided by HAP Housing. The family is back in shelter.

Considering Local Factors

Comparing rapid re-housing programs across different communities is difficult because they can be tailored to suit local needs while still keeping to HUD’s core funding criteria. Oliva acknowledges that there is a wide variation in project models from community to community. “Rapid Housing in San Francisco or Los Angeles is not going to look the same as in Omaha. What is really, really important is that there is a housing search and placement component inside of any rapid re-housing program. Sometimes, rapid re-housing can serve as a bridge until other subsidies and programs are put into place for the family,” she says.

Many programs appoint housing navigators, who work directly with families to assess their needs and with the landlords to find suitable properties. It is important for those navigators to know what barriers the family faces, if, say there is poor credit or a criminal background, or some health issues that have not been addressed, according to Ann Linkey, division manager, homeless and rental counseling/supportive housing at Tabor Community Services, which runs the STIL program in Lancaster, PA. Then, the navigator can talk intelligently and proactively with the landlord.

In Omaha, NE, Heartland Services runs rapid re-housing in a three-county metro area that includes Polk County, IA. In the early days, when they received their first HPRP grant, the programs struggled to help their families find appropriate housing and to keep clients housed. Since then, they have realized they need to provide more intensive case management services up front.

“We have been a lot more successful after adding a housing advocate position,” says Rehousing Director Jody Jackson. Their average length of stay in rapid re-housing is about five months with a maximum of 12 months, and they are placing people in permanent housing, on average, in about 40 days. She would like to see them get that period below 30 days. Her most recent quarterly data shows that about 90 percent of the people who exited rapid re-housing a year ago had not returned to a shelter.

But, as in most communities, there is no way for Jackson to know if someone moved out of town or doubled up with relatives. “We know they did not turn up homeless again. Unfortunately, we do not have resources to follow up with people. That is one of the flaws with it.”

“We felt that rapid re-housing is most successful when you are focusing not just on getting people housed, but making sure they have the income needed to support the housing.”

—Nick Codd, Associate Director,

Building Changes

In Houston, which received the highest HUD score of any COC that applied for Tier 2 funding in FY 2015–16, the move to rapid re-housing has involved many moving parts and some missteps along the way. In the beginning, when they first received HPRP stimulus funds, the programs were run in a piecemeal fashion, with four different entitlement jurisdictions that “really did not talk to each other,” says Thibaudeau of Houston’s Coalition for the Homeless.

It took “a lot of tough meeting and working together” for all the jurisdictions within the Continuum of Care to resolve the chaos. “We came together and aligned our funding under common standards and business rules.” Thibaudeau concedes they “probably underestimated how tough it would be to implement a rapid re-housing program. As we often say to each other when we get really frustrated, we are the ones with an office and roof over our heads. We are not the ones in crisis or in a state of shock. We should be the ones doing the heavy lifting.”

Since January 1, 2015, every homeless candidate for rapid re-housing in the Houston metro area talks first with a neutral assessor, who runs them through the same sets of questions in order to determine whether someone should be referred for long-term permanent supportive housing or rapid re-housing. “We were really able to make sure that those who did not need long-term services and subsidies but have a lot of needs, including zero income, were guaranteed to get served. We standardized how all case managers act and really

brought it to a system level.”

Houston’s Coalition for the Homeless also considers good landlord relations so critical that they regularly host “landlord appreciation” events and legal clinics to attract them to meetings. The city has established a system-wide landlord-marketing group, where all the communications people from all the organizations speak with one voice to recruit landlords. “We do not talk about the family’s needs. We talk about the landlord’s need to have income,” says Thibaudeau.

When Will Evans, vice president of housing and supportive services at Community Connections in Jacksonville, FL,—a city of almost 870,000 at the northern tip of the state—started converting over to rapid re-housing, he had already established a strong network of some 60 landlords from his days of running scatter-site transitional housing. He got their support by pounding the pavement. “I had to go out to the churches and say, ‘I am trying to end homelessness. If any of you are landlords, raise your hands.’”

Evans recently calculated that families in his city needed to make $19.76 an hour in order to afford the median rent for a two-bedroom apartment. The average wage in Jacksonville? About $8 an hour. Taking inspiration from programs he has seen up north, he proposed that some families—who have been rapidly re-housed for six months but have not made enough progress toward self-sufficiency—share the rent on a home with another homeless family. The idea does not sit well with everybody, but it has worked out well for a few families so far. “It is better to share a house than to be homeless,” he says. “No one is saying it has to be permanent.”

Programs Struggle without Available Housing

Even good relationships with landlords do not solve the affordable housing crisis in many communities. A 2015 report from the Urban Institute on rapid re-housing noted that most evidence shows that the programs do help families exit homeless shelters, with low rates of return to shelter. By the same token, it said, rapid re-housing does not cure the long-term problem that plagues many communities: a lack of affordable housing. “After families exit rapid re-housing they experience high rates of residential instability. Many move again or double up within a year and face challenges paying for rent and household necessities.”

In Washington, DC, a shortage of affordable housing is putting a strain on rapid re-housing efforts. “The barriers that some of our families have—whether it is for lack of credit, poor credit, evictions, or lack of income—make it harder for a landlord to want to work with our clients when they can get someone who is a market-rate renter,” says Allison Tucker, rapid re-housing manager at the Department of Human Services for the District of Columbia.

Housing attorney Max Tipping, an equal justice fellow at the Washington Legal Clinic for the Homeless, says his client families in rapid re-housing often find themselves in poorly maintained units. “All these families are being driven into the subprime rental market, where all the units are in poor shape.” He says one of his clients has filed a complaint against a rapid re-housing landlord because he originally quoted the rent at $1,000 per month and then raised it to $1,350 when he learned she was in the rapid re-housing program. He says the landlords “know the city is desperate and they are upcharging to rent these out.”

Across the country in Los Angeles, the housing market is similarly tight. “In Los Angeles, the vacancy rate is less than two percent and it is not uncommon to find homeless families living in their vehicles,” says Katie Hill, deputy CEO of PATH Beyond Shelter in Los Angeles. “Even when families get vouchers for Section 8 subsidized housing, it is often impossible to find them an apartment.”

Los Angeles County uses a coordinated intake and assessment system, called the Homeless Families Solution System, where providers work closely together to identify resources for homeless families that go beyond rapid re-housing, such as permanent supportive housing. The system allows for “unprecedented information sharing and collaboration along different areas of Los Angeles County,” she says.

“You really have to look at a rapid re-housing program as something that is customized,” says Hill. That means having service providers who are able to look closely at each case and “do whatever it takes” to get the family stably housed. “Sometimes it is worth giving rapid re-housing a shot—even for high-barrier individuals,” says Elizabeth Heger, PATH’s director of family programs.

Overall, Heger and Hill say, rapid re-housing has been a success. A year after leaving the program, they have found over 90 percent of families stayed housed—meaning they did not show up at another Los Angeles shelter.

Best Practices Matter

While rapid re-housing programs may differ widely in their details, administrators cite best practices that are key to success. They include: a centralized, community-wide intake program; client-centered case management with an array of services that are tailored to each family; a network of community partnerships with government agencies and nonprofits; strong relationships with local landlords; and workforce development services.

“To do rapid re-housing well, you have to be a lot more nimble and a lot more creative,” says Joyce Lavery, CEO and executive director of Safe Haven Family Shelter in Nashville, TN. “You have to keep up with families and customize services.”

“For us and others who have found rapid re-housing very successful, it is not housing only,” she asserts. Rather, she says, families “have the autonomy and dignity to make certain choices without a shelter staff dictating what they are.”

Safe Haven clinical supervisor Hannah Evans cites the success story of a high-barrier, two parent family with one child at home and another on the way. Five of their previous children had been taken into protective custody because of some concerns about abuse and neglect, and they had problems with past rental arrears.

Despite those issues, in less than two weeks, Evans had moved them into an apartment with community rapid re-housing funds. Once they were housed, they were able to work with the couple on their parenting skills. She found a nurse to help the mother bond with her new baby through breast-feeding. The husband is now seeking full-time employment and they have joined a local church. Safe Haven also helped them secure a Section 8 voucher. “To keep a family in a shelter that has that much trauma is not always helpful, even in a wonderful shelter like ours,” says Lavery. “If you can get them into a permanent home where they can act as a family, it is undeniably a healthier alternative.”

Workforce development is an important component of many rapid re-housing programs. At Building Changes in Seattle, which funds rapid re-housing in three Washington counties, “one of the things we do is we identify new and emerging best practices that show promise to improve services for homeless families,” says associate director Nick Codd.

For a rapid re-housing pilot project in King County in FY 2014–15, Building Changes paired the short-term subsidies and case management of rapid re-housing with employment navigation services. “We felt that rapid re-housing is most successful when you are focusing not just on getting people housed, but making sure they have the income needed to support the housing,” says Codd.

By most accounts, rapid re-housing certainly does not end poverty as we know it, but rather ends an instance of homelessness, and is sometimes the beginning of families getting back on their feet. In Washington, DC, Tytianna Douglas had no family to turn to for help when she became homeless two years ago. The 24-year-old single mother, who had aged out of foster care, got placed in a Day’s Inn motel for a year with her kids. Then, she heard about the rapid re-housing program, and Douglas, who was pregnant with her daughter at the time, managed to get a two-bedroom unit where she pays $118.40 per month. Her now year-old daughter is in day care, while she works a part-time, minimum wage job as a hostess.

After a succession of less than satisfactory case managers, who, Douglas says, mostly just asked her about her budget and collected her rent once a month, she finally has landed on one she can really talk to and is receiving help connecting her with the services she needs.

“At the moment, me and my children are housed, so I cannot complain,” she says. “It is not permanent, so you got to think ahead. Sometimes, it can be overwhelming.”

* Editors’ Note: A sidebar to this article summarizes HUD’s definition of rapid re-housing, which outlines three program components that must be in place for funding eligibility, while still allowing for variations based on local needs and circumstances.

Resources

St. Joseph’s Villa www.neverstopbelieving.org/services/housing-homeless-services/ Richmond, VA ■ U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development www.http://www.portal.hud.gov/hudportal/HUD Washington, DC ■ Homestretch www.homestretchva.org Falls Church, VA ■ Safe Haven Family Shelter www.safehaven.org Nashville, TN ■ Houston Coalition for the Homeless www.homelesshouston.org Houston, TX ■ PATH Beyond Shelter www.epath.org/site/PATHBeyondShelter/home.html Los Angeles, CA ■ Tabor Community Services www.tabornet.org Lancaster, PA ■ United States Interagency Council on Homelessness www.usich.gov Washington, DC ■ The Washington Legal Clinic for the Homeless www.legalclinic.org Washington, DC ■ Heartland Family Service www.heartlandfamilyservice.org Omaha, NE ■ HAP Housing www.haphousing.org Springfield, MA ■ Urban Institute www.urban.org Washington, DC ■ Building Changes www.buildingchanges.org Seattle, WA ■ Community Connections www.communityconnectionsjax.org Jacksonville, FL.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

A Better Life for the Whole Family: The Two-Generation Approach

by Mari Rich

My personal obsession right now is how disconnected we are from what we really need to be talking about with poverty. We talk about work or training for parents, or we talk about early childhood for kids. But I do not see how we can help the children without trying to help their parents as well. We have to have a serious national discussion about helping families together.

—Paul Krugman

Nobel Laureate and New York Times columnist

The staff and clients at Our House in Little Rock, AR, are engaged in much more than mere discussion of the holistic, multi-faceted method—often called the “two-generation approach”—to which Krugman refers. They are putting it into everyday practice, with heartening results.

A Couple with Entrepreneurial Ambitions

Marie and Omar Rahmaan were struggling to make ends meet despite working long hours: Marie cleaned houses and dreamed of launching her own janitorial company, and Omar served as an assistant produce manager at a local supermarket with hopes to one day set up his own food truck. He envisioned serving breakfast and lunch, accompanied by cups of his special tea, which Marie always described as the best she had ever tasted.

A disproportionately large percentage of their income went to paying the rent on a home big enough for their four children—eight-year-old Lamarcus, six-year-old Jayden, and three-year-old twins Autumn and Amberlee. They might not have minded that fact quite so keenly had their landlord been willing to make desperately needed repairs. The couple had begun to fear for the health and safety of the entire family in the aging and neglected structure.

The Rahmaan Family benefits from the “two-generation” approach offered at Our House. This approach emphasizes the importance of considering a family unit as a whole, accounts for the needs of everyone in the family, and acknowledges that a child’s success is inextricably linked to their parent’s success and stability.

Add to that a vehicle urgently in need of a mechanic’s attention (they had been forced to give up a more reliable car when they could not make the payments), and it seemed like the couple might never be able to fulfill their entrepreneurial ambitions and set their children on whatever individual paths to success they might choose. Each of their offspring, it was apparent, had a distinct talent: Lamarcus possessed a formidable natural intelligence, regularly bringing home report cards that would make any parent proud; Jayden was the artist in the family; and the twins, with their ready grins and propensity to chatter, could charm anyone they met.

Marie, while frustrated and discouraged by the situation, was determined to turn things around. Strapping the girls into their double stroller one day, she set out to walk to Our House, an appealing multi-building campus with a colorful playground and a bright sign proclaiming “Hope for the Working Homeless,” about a mile from her neighborhood. She knew the current living conditions of her family’s home were uninhabitable.

An Organization with an Ambitious Agenda

If it were not for that sign and playground, it would be easy to mistake Our House—with its tidy buildings spread across a seven-acre campus—for a bustling community college. And like a college, where students can take advantage of course offerings across a range of disciplines, clients at Our House (among them the formerly homeless, currently homeless, and near homeless) have access to a range of facilities and services to meet their needs.

A newly-renovated Career Center can accommodate as many as 120 people a day for job training and employment counseling, and adults seeking to advance their educations can earn GEDs or get advice about college. Some 90 children attend after-school and summer programs geared just for them, and the campus includes Little Learners, an early learning center for the 60 youngest clients. A staggering array of other services is available, including meal programs, a clothing bank, AA meetings, HIV testing, parenting classes, financial literacy instruction, mental health treatment, and more.

Our House offers an array of facilities and services to clients on a seven-acre campus. The newly-renovated Career Center can accommodate up to 120 people per day for job training courses, while the Little Learners facility, an early learning center, provides educational day care to nearly 60 children.

“Behind the scenes, we have more than 200 agencies and organizations that partner with us,” Our House’s executive director, Georgia Mjartan, explains. “The services provided by our partners take place on-site and are fully integrated with those provided by our staff so that our clients have a totally seamless experience. We have physical and occupational therapists, social workers, employment coaches, teachers, child care providers, and case managers who meet weekly to coordinate and collaborate. A group of bakers bring birthday cakes for the children. Others contribute gifts that meet both the children’s and their parent’s needs. We are even working closely with two agencies on pilot quality improvement programs to ensure access to services meant for people like our clients who, in the past, have fallen through the cracks.”

Housing options on the campus include two bright, safe dormitories (one for women and children, the other for single men), and an apartment-style residence for families, which is where Marie and Omar now live with their children. Their unit has two bedrooms and a bathroom, and they share a communal kitchen and living room with other families.

“You might have to give up some of the privacy and freedom you were accustomed to,” Marie says, “but in return, you are getting the chance to build an entirely new life for yourself and your children.”

An Approach that Comes from Outside the Box (and Way Outside the Silo)

Ben Goodwin, the organization’s assistant director, says that Marie is hitting upon a key aspect of the two-generation approach when she speaks about a better life for both the adults and the children in her family. “It might seem obvious to consider the family unit as a whole,” he says, “but in reality, most programs focus on either the parent or the child.” He continues, “A workforce training program, for example, might be of great use to a single mother, but if she does not have reliable child care, and the program’s organizers have set it up so that participants must remain until five o’clock each evening, she may not be able to stay. Similarly, if a child attends an enrichment program whose organizers hold parent conferences during the day, those who work at jobs with inflexible hours or attend school themselves might not be able to get there and might, as a consequence, be misconceived as uninvolved or uncaring. Those scheduling pitfalls are evidence that an organization is focusing on one generation only, often to the detriment of the other.” A two-generation approach, by contrast, takes into consideration the needs of everyone in the family, acknowledging that a child’s potential is inextricably linked to parental stability and well-being.

Unchecked, a snowball effect can occur in struggling families. A parent without reliable child care may miss days of work and lose his or her source of income, necessitating a move to substandard housing. Poor living conditions can cause or exacerbate health problems (such as when an asthmatic child is exposed to mold), making it difficult for the parent, who now has the added burden of frequent doctor’s visits, to look for another job.

Whenever possible, programs for both parents and children are coordinated to ensure that all family members are engaged and learning.

“It is not effective to place issues in silos, treating them in isolation from each other,” Mjartan asserts. She goes on to describe a survey Our House recently gave to each of its employees, asking them whom they consider to be their primary clients: adults or children. “More than 80 percent of them—whether they are pre-school teachers or financial literacy instructors—feel that they are serving both generations equally. That perfectly encapsulates what we are doing here.”

The result is that at Our House, child care providers understand that working parents might not be able to attend every holiday festivity or art show, and job coaches appreciate that the aspiring employees whom they are counseling might need to take their children’s physical, social, and emotional needs into account when choosing a career. (Mjartan recalls one child who, when asked what occupation he would like to see his then-absent father pursue, movingly replied, “a farmer instead of in prison.”) Whenever possible, programs for both groups are coordinated. While an adult money-management course is taking place, for example, a similar class for children might be held at the same time, so that all family members are learning relevant skills; if a parenting class is scheduled for evening hours, child care or an enrichment activity is made available.

Because Our House staffers are not working in silos, no client does either. Marie points out that while much of her time is spent parenting, the staff members at Our House also have great respect for her as a fledgling entrepreneur. Illustrating that dual role is the fact that among the most valuable classes she has taken recently have been one on becoming an effective advocate for your child and another covering the safety of the cleaning solutions she will be using when she launches her janitorial service. (Additionally, she and Omar are valued volunteers in the Our House community, pitching in to sort donations to the clothing bank and do other needed tasks.)

“When you are asked what is important to you and what your goals are, it is natural for parents to immediately think of what they want for their children—for example, for them to do well in school and have good lives and careers,” Marie and Omar say. “But we have come to understand that our goals are just as important, because if we are not focused and successful, it will be much harder for them to grow into focused, successful adults.”

Marie Rahmaan, mother of four, is also a fledgling entrepreneur. At Our House she was able to take one class on becoming an effective advocate for her children and another class covering the safety of the cleaning solutions she will be using when she launches her janitorial service.

An Idea Whose Time Has Come

Organizations across the country are beginning to see the wisdom of taking a two-generation approach. Many are members of the Aspen Institute’s growing Ascend Network (see sidebar), which serves as a hub for breakthrough ideas and collaborations that move children and their parents toward educational success and economic security.

While not every group is able to provide services as comprehensive as those at Our House, they are endeavoring to expand their traditional missions to encompass two-generation practices. The Connecticut-based All Our Kin focuses on the child care sector, but does so in a way that benefits participants at every level: the organization trains and licenses child care providers, resulting in much higher pay to help them build better lives for their own families. (A significant number go on to earn college degrees in early childhood development or related areas.) Children, in turn, gain access to a stellar level of care and have demonstrated a marked increase in school readiness. Each provider trained and licensed by All Our Kin makes it possible for four to five parents to return to the workforce. The providers supply high-quality, flexible child care, and the program as a whole is said to generate more than $7 million per year in macroeconomic benefit to the New Haven region. Another Ascend Network member, 2Gen Equity, directs its energies towards young, single mothers in the San Francisco Bay area, inviting them to take part in an intensive 24-month career and life development program and assigning them a family “coach.”

While colleges are not typically thought of as doing the job of social service agencies, some are now acknowledging that struggling young parents comprise a segment of their student body and are taking steps to establish a two-generation approach at their institutions. Hostos Community College located in the New York City borough of the Bronx and a member of the Ascend Network, recently launched a program for low-income student-parents to accelerate the completion of their degrees through free summer courses (which are often not covered through financial aid), while inviting their children to attend an on-site learning center and summer camp.

By the Numbers

Mjartan and Goodwin are firm believers in objective measurements and hard data. The resulting figures are impressive. A recent study found that 72 percent of the clients in their housing programs leave with money in a savings account; each year some 500 homeless and near-homeless adult clients find full-time jobs with more than 275 different central Arkansas employers; 88 percent of the school-age children in Our House’s enrichment programs show improved grades in math and English; and 98 percent of those taking part in the early childhood education programs meet expected developmental milestones.

That kind of progress admittedly requires many resources. Our House has an annual budget of $2.5 million and benefits each year from $1.6 million in donations of goods and services and the work of 3,000 volunteers, who collectively contribute more than 24,000 hours.

Our House offers a wide range of services for all members of the family. These services include parenting classes, after-school and summer programming, financial literacy instruction, and an early learn center.

The members of the Rahmaan family might argue that the results are priceless. Lamarcus was recently accepted into an Our House leadership development program, and Jayden has had his paintings displayed in a show for young artists. A lucrative janitorial service and gleaming new food truck seem like distinct possibilities, rather than mere dreams. It could be that residents of Little Rock may soon get to taste Omar’s tea for themselves. “Really, it is just a matter of getting the proportions of honey and lemon right,” he admits. “Marie probably thinks it tastes so good because she knows I make it with love.”

Resources

Our House www.ourhouseshelter.org Little Rock, AR ■ Aspen Institute Ascend Network www.ascend.aspeninstitute.org/network Washington, DC ■ All Our Kin http://www.allourkin.org Bridgeport, CT ■ 2Gen Equity www.2genequity.org San Francisco, CA ν Hostos Community College www.hostos.cuny.edu Bronx, NY.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

Are We Creating Chronic Homelessness? The Past, Present, and Future of Federal Homelessness Policy

by Barbara Duffield

Barbara Duffield is the Director of Policy and Programs for the National Association for the Education of Homeless Children and Youth (NAEHCY).

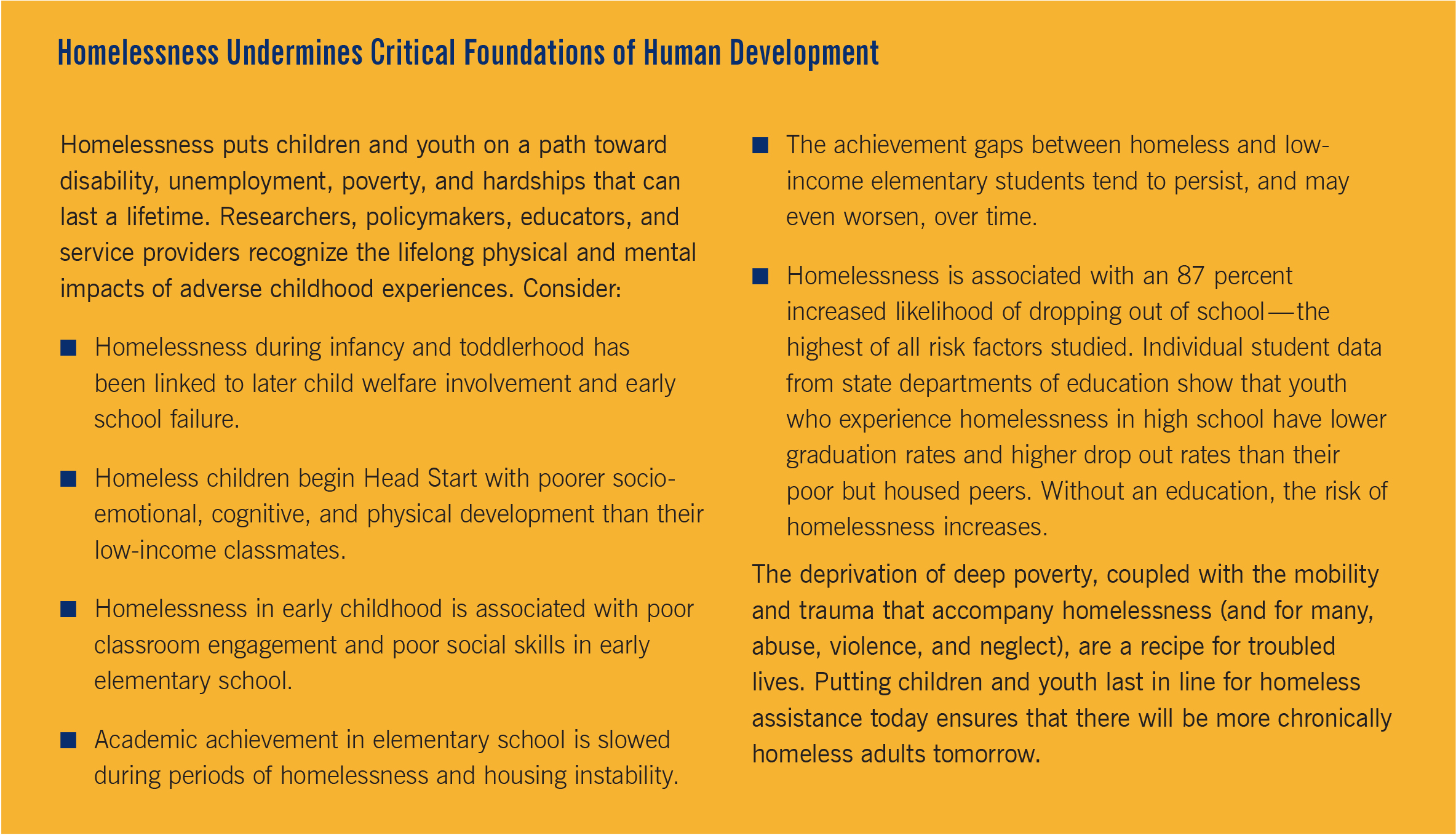

As the November presidential election inches closer, many organizations are putting the finishing touches on their “transition” plans—their vision and recommendations for the next administration. This, therefore, is an opportune time to re-examine the assumptions and the outcomes of current federal policy on homelessness. A review of available evidence makes clear that in order to address homelessness now and prevent it in the future, we must focus on the complex realities and comprehensive needs of homeless children and youth—by adopting an honest definition of homelessness, retooling homeless assistance with child and youth development at the forefront, and ensuring that early care, education, and services are linked directly to any family homelessness housing initiatives.

Evaluating the Chronic Homelessness Priority

The Obama Administration’s strategic federal plan on homelessness, “Opening Doors,” established the national goal of ending chronic and veteran homelessness by 2015. That goal, which extended the (George W.) Bush Administration’s target of ending chronic homelessness by 2012, has since been pushed back two more times, to 2016 and then 2017—despite the fact that the federal government has focused its energy and funding overwhelmingly on chronically homeless adults since 2004.

In its quest to end chronic homelessness, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) has changed the way it scored local communities’ applications for homeless assistance funding and has used its formidable administrative and regulatory power to force communities to maximize services for chronically homeless people throughout the country, regardless of local circumstances and needs. An examination of ten years of this approach reveals flawed economic logic, a failure to “end” chronic homelessness today, and a paradigm that might actually sustain chronic homelessness into the future.

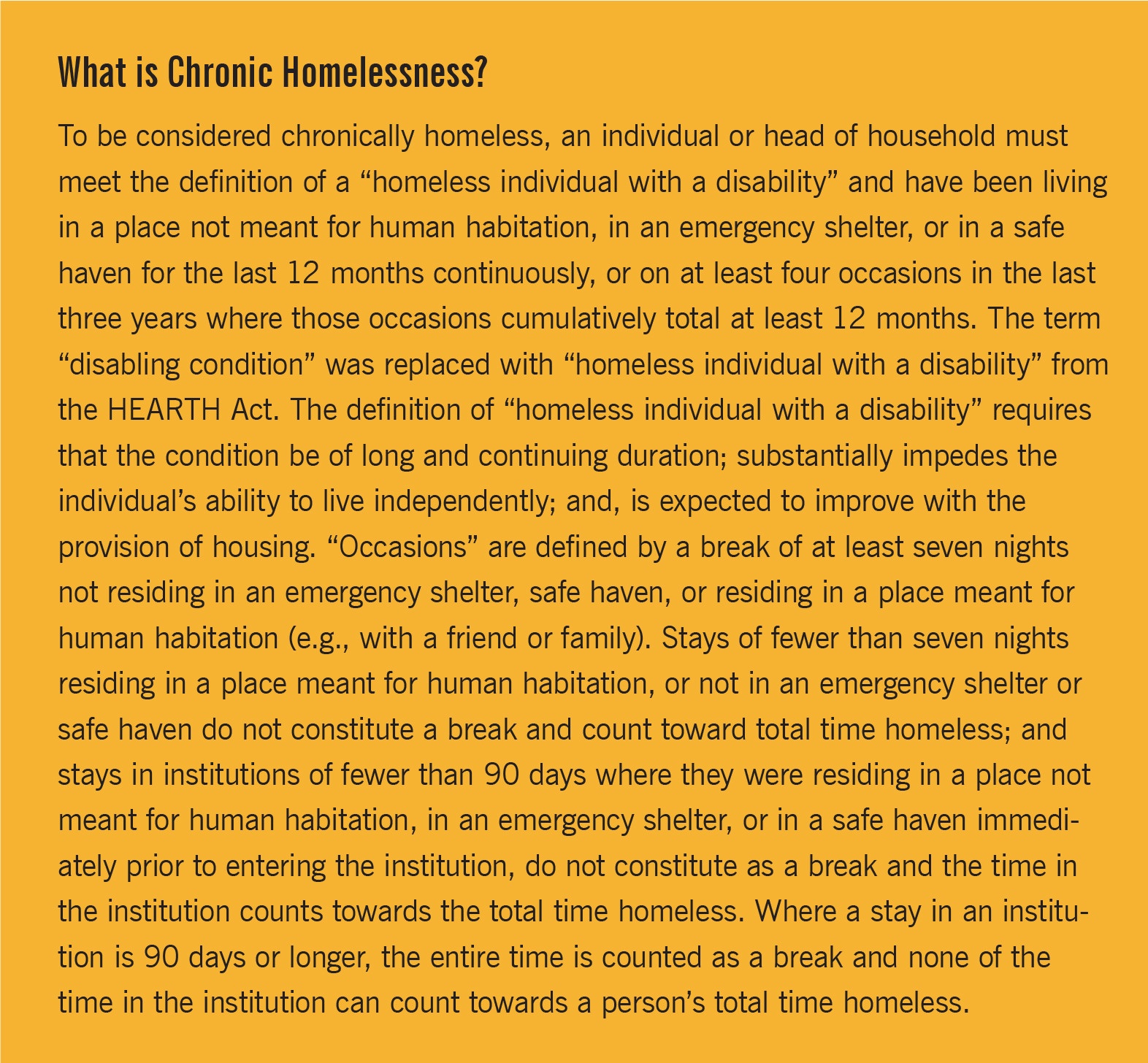

The problems with the chronic homelessness priority begin with how chronic homelessness is defined. What is meant by “chronically homeless?” HUD now considers an individual or head of household to be chronically homeless only if he or she meets the definition of a “homeless individual with a disability” and has been living in a place not meant for human habitation, in an emergency shelter, or in a safe haven for the last 12 months continuously, or on at least four occasions in the last three years where those occasions cumulatively total at least 12 months. Last year HUD promulgated regulations to further restrict the definition of what constitutes chronic homelessness, adding layers to an already complex definition (see the detailed definition, sidebar, page 25). The narrowness of this definition excludes many homeless single adults, and even more parents and children.

The economic justification for the chronic homelessness priority is equally flawed. The original argument was that targeting resources to chronically homeless people will “free up” resources to serve other homeless populations—eventually. Yet, after more than a decade of these policies, neither HUD nor the United States Interagency Council on Homelessness (USICH) has freed up resources for other homeless populations. They have not explained when or how any savings that might someday materialize will be passed on to other homeless populations. To the contrary, both agencies continue to fight efforts to allow local communities to prioritize other populations with HUD homeless assistance, even when those communities repeatedly identify other, more urgent needs.

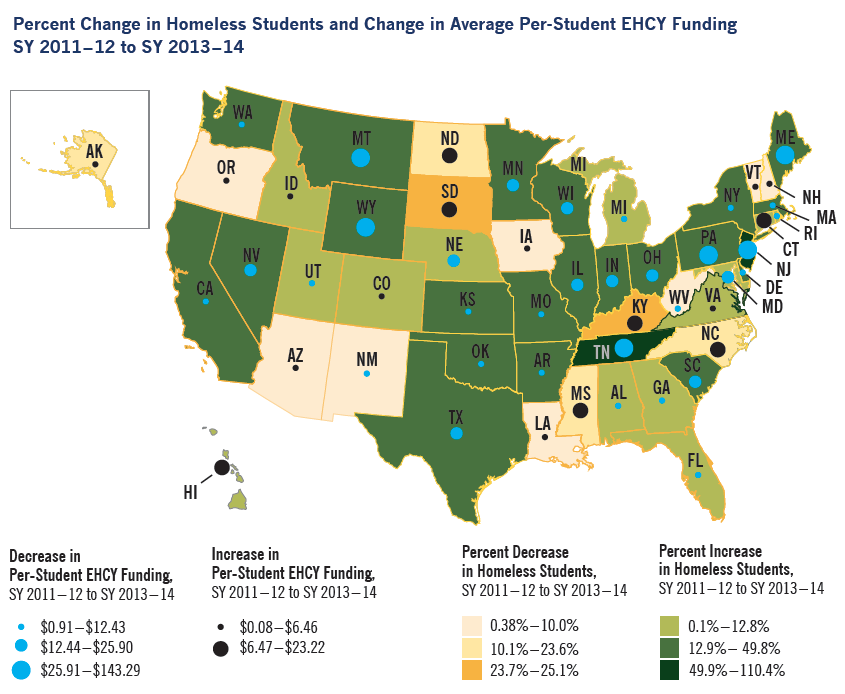

The “trickle-down” feature of the chronic homelessness priority is also absent on the ground. Programs for homeless families have not seen an increase in resources as a result of the supposed decrease in chronic homelessness. In fact, many of these programs have lost funding as a direct result of HUD’s emphasis on chronic homelessness. This loss is compounded by the fact that many private foundations and local and state governments have followed the federally-established priority on chronic homelessness. HUD’s Point-in-Time counts, which exclude large segments of the homeless population, prop up these misguided federal policies, and encourage redirection of private and local funding.

Despite the failure of the trickle-down economic justification for the focus on chronic homelessness, one still might accept the campaign to end chronic homelessness if it effectively addressed the plight of chronically homeless people. But what about those triumphant headlines trumpeting the end of chronic homelessness in various communities? Is the end of chronic homelessness in sight?

Certainly, some communities have seen significant reductions in the counts of chronically homeless people, although HUD’s creative definitions may well have contributed to the reported successes. In addition to the narrowing of the definition of chronic homelessness mentioned previously, HUD also invented the term “functional zero.” This Orwellian term does not mean that there are no more chronically homeless people in the communities that have reached “functional zero.” Instead, it means that the availability of resources in the community exceeds the size of the population needing the resources. Whether homeless people use those resources or are successful with them is not relevant. Under “functional zero,” people remain chronically homeless on the streets even after their communities have “ended” chronic homelessness.

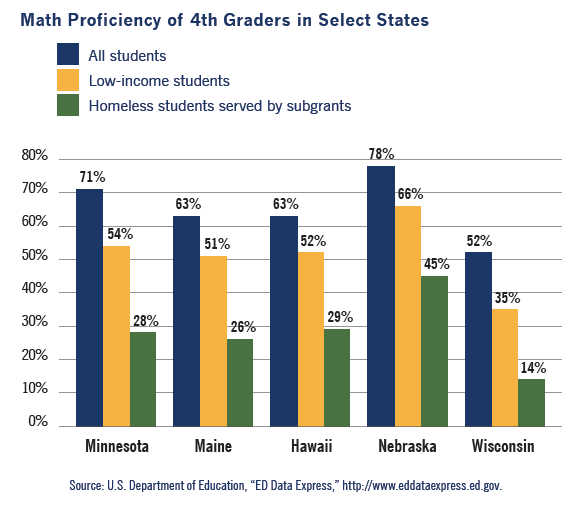

Meanwhile, other headlines on homelessness describe our national predicament more clearly and forthrightly. Family homelessness has reached record levels in many major cities, leading some officials to declare a state of emergency. Public schools are yet another barometer of this disastrous state of affairs: schools identified 1,301,239 homeless children and youth in 2013–14, a seven percent increase over the previous year, and a 100 percent increase since the 2006–07 school year. The number of young homeless children enrolled in Head Start increased by 92 percent over approximately the same period.

As some types of homelessness are declared to be dwindling while others explode, the chronic homelessness priority reveals another, more fundamental weakness. Targeting assistance to people who currently meet the definition of chronically homeless does nothing to prevent chronic homelessness from happening in the first place. While some of today’s chronically homeless adults are receiving supportive housing to end their homelessness, by relegating children and youth to the end of the queue in the nation’s plan to end homelessness, and failing to promote assistance that meets their unique needs, we ensure a continuous flow of homeless young people falling through the cracks, many to become “chronically homeless” themselves as the system continues to fail them over time.

Cartoon by Diana Bowman.

Download cartoon here.

‘Ending’ Family Homelessness by 2020?

As a secondary goal, the Administration’s “Opening Doors” plan proposed to end youth and family homelessness by 2020. Yet, it was not until this year—the final year of the Obama Administration and just four years before the deadline to end family homelessness—that HUD’s budget called for any focused effort on family homelessness. This came in the form of an $11 billion request in mandatory funding over ten years for housing assistance (mostly Housing Choice Vouchers, plus new funding for rapid re-housing) for families who meet HUD’s limited definition of homelessness.

HUD’s FY 2017 family homelessness proposal is regarded by most observers as dead on arrival, due to the size of the funding request, the limited legislative calendar, and the tense fiscal and political budget climate. The proposal therefore is being positioned as the centerpiece of family homelessness policy for the next administration. As such, it merits careful consideration.

The claim that HUD’s proposal will “end family homelessness” is based on an assumption that family homelessness is primarily, even exclusively, a problem of housing affordability, and can be remedied by the provision of short- or longer-term housing assistance. HUD supports this claim with preliminary findings from the Family Options Study, which found that families offered a housing voucher experienced significantly less homelessness, fewer moves, and better outcomes than families assigned to other interventions. Yet questions have been raised about the methodology and design of the Family Options Study, casting doubt on whether its preliminary findings are as conclusive as stated. At a minimum, the study demands more scrutiny before serving as the justification for a massive investment that purports to “end” family homelessness in the United States.

Framing family homelessness as primarily a housing problem appears to be rooted more in wishful thinking and ideology than in the reality of homelessness experienced by parents and children—a complex problem caused by deep poverty, and exacerbated by lack of education, lack of child care, lack of employment options, and a severe shortage of affordable housing.

But there is another equally significant problem: putting aside its dubious premises, HUD’s family homelessness proposal is limited to families who meet HUD’s restrictive definition of homelessness—those in shelters or in unsheltered locations. It therefore excludes over 80 percent of the homeless children and youth who are identified by public schools and early care programs, but who do not meet HUD’s definition because there are no shelters, shelters are full, or shelters restrict eligibility. These children and their parents have no other option but to stay in motels or temporarily with other people in crowded, precarious, and often unsafe situations that jeopardize children’s health, safety, and development. HUD’s steadfast refusal to acknowledge that these families, children, and youth are homeless and that homelessness fundamentally looks different for families, children, and youth bodes poorly for any hope of ending family homelessness, chronic homelessness, or any other type of homelessness.

Looking to the Future

What is needed now, in this time of reflection and transition, is a new paradigm that connects cause and consequence throughout the human lifespan—from before birth through adulthood. This new paradigm must reject the grossly mistaken assumption that homeless parents and children simply need housing—and that they are less vulnerable, easier to serve, and have fewer disabling conditions simply because they are not visible on the streets. We must contend with the complexity of family homelessness—its many layers, causes, and impacts.

To do so, we must recognize that, while housing is a critical need of homeless families, it is not their only need: housing is necessary, but not sufficient. Nor are “mainstream services” for homeless parents and children the panacea claimed by some advocates. Mainstream services are often inaccessible, not only due to lack of funding, but because homelessness itself creates barriers to accessing them: high mobility, lack of transportation, missing documentation, and lack of outreach all create barriers to accessing child care, early childhood programs, food, employment, education, and health care. We are setting families up to fail if these barriers are not addressed with the same vigor that the federal government demanded of communities in assisting chronically homeless adults. We must acknowledge that homelessness presents qualitatively different perils for children and youth, necessitating different standards for eligibility and different standards for assessing risk. Their brains, bodies, and spirits are developing now (see sidebar, page 28, on impact of homelessness on human development). They cannot wait any longer to become a priority, or for solutions that meet their unique and comprehensive needs.

What should drive the vision of the next administration? We propose a realistic, two-generational approach to family and youth homelessness, grounded in the interconnected and equally vital roles of housing, education, early care, and services.

Indeed, without early care and education, the prospect of affording any kind of housing as an adult is slim, making today’s homeless children more likely to become tomorrow’s homeless adults. A two-generational approach to ending family homelessness calls for full engagement of child care, early learning programs, schools, and other children’s services as essential and equal partners with housing agencies and homeless service providers. In addition, homeless assistance services, program design, outcomes, and policies must be built around the specific and unique needs of children and youth as clients—with needs equal to, but separate from and different than, the needs of their parents. While these measures are ultimately the best long-term approach to addressing both single adult and family homelessness, they cannot be packaged neatly into a 10-year-plan, “ending” homelessness by 2020, or in other marketing campaigns masquerading as public policy.

In sum, if the national dialogue and outline for action on family homelessness is limited to initiatives that provide housing for a narrowly and artificially defined segment of homeless children, youth, and families (that is, only those who meet HUD’s outdated definition of homelessness), minimize the role of essential services (including education), and ignore or treat as an after-thought children’s unique developmental needs, we will be generating poverty and homelessness for the foreseeable future. We will not truly end chronic homelessness, or any other kind of homelessness, until the complex realities and comprehensive needs of homeless children and youth take a front seat in federal homelessness policy. Only then will we see true cost savings and real homelessness prevention, albeit with a longer time frame than a presidential administration.

Resources