Publisher’s Note

Dear Reader,

The Summer 2017 issue of UNCENSORED looks beyond where homeless families sleep to another core issue—their health. Health plays an important role in predicting the future success and productivity of homeless children and their families. Simply put, health problems can not only lead to homelessness, but can make it difficult to escape this most extreme form of poverty.

Our first article, “Outside the Box and Inside the Shelter,” examines the avoidable tragedy of unintentional injuries among children experiencing homelessness and the increased risks they face. Safety hazard education is key to reducing these preventable injuries, and we explore an inventive method of reinforcing the facts and helping parents become their child’s greatest advocate.

Substance abuse is another health issue that disproportionately affects those experiencing homelessness, with many of the factors that lead to homelessness also contributing to the development of addiction. There can be many barriers to receiving help, with homeless families facing more than most. In “Sheltered from the Storm,” we profile a Massachusetts program aimed at reducing those barriers with a shelter-based treatment program.

Moving deeper into the arena of health lays the topic of mental health. When it comes to homelessness, the day-to-day stress and anxiety experienced by children and families leads to an increased risk of depression, anxiety, behavioral issues, and more. “Play, Art, Caring” looks at programs across the country that are committed to the mental health and stress reduction of this vulnerable population.

Our National Perspective delves into the relevant key findings of ICPH’s recent report, “More Than a Place to Sleep: Understanding the Health and Well-Being of Homeless High School Students.” The report explores differences in risk behaviors and health outcomes between homeless high school students and their housed classmates.

As always, please continue to share your ideas, comments, and stories with us at info@ICPHusa.org and via social media.

Sincerely,

Ralph da Costa Nunez, PhD, Publisher

President and CEO, Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

Outside the Box and Inside the Shelter: Preventing Injuries to Children Who Are Homeless

by Susan Fliesher, Mary Curtis, and Katie Linek Puello

The terms unintentional injury and accident are often used synonymously, but are in fact very different. The word “accident” implies an incident was random and unpredictable. Unintentional injuries on the other hand, are both predictable and more importantly, preventable—especially when it comes to children.

According to limited research, homeless children are statistically more likely to suffer unintentional injury than housed children from poorer families.

Unintentional injuries, such as suffocation, choking, poisoning, falls, fire or burns, cuts, drowning, and motor vehicle accidents, can be predicted based on a child’s age, location, behaviors, and more. For example, young children who put things in their mouths are at increased risk for choking on small objects and poisoning. Toddlers are very curious and love to run, climb, and explore, putting them at an increased risk for falls which can lead to head injuries, broken bones, and cuts.

Despite the predictability of these injuries, they continue to be a leading cause of death and disability for children and adolescents. The Child Trends Data Bank Report on Unintentional Injuries reported that over 8,000 children annually—more than 20 per day—die in the U.S. because of such injuries. The report further estimated that for every child death resulting from an injury, more than 1,000 children receive medical treatment for non-fatal injuries. Much of this data is collected by medical offices and hospitals, but how many more children are injured who do not seek medical help?

In addition to the tragedy of events that leave a child with lifelong injuries or disabilities, the cost to society is staggering. In 2012, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for Injury and Control estimated the costs related to childhood injuries at $87 billion dollars annually in the United States. The cost of an injured child’s medical care is often considered; however, many forget the secondary expenses—the lost wages of a family member staying home to care for an injured child, equipment, needed environmental changes, and more.

More than 8,000 children die annually due to unintentional injuries, many of which are predictable if a parent knows what hazards to look for in their environment. How many safety hazards can you spot in this picture?

Homeless Children and Unintentional Injuries

The risk of such injuries is even higher among homeless children. One study found that when housed, lower socioeconomic families with children were compared to homeless families with children, the rate of unintentional injury was 13 percent higher among the homeless.

Why this occurs more among homeless children is unclear. “Is it because they are poor?” asks Mary Curtis, a professor at the Goldfarb School of Nursing at Barnes Jewish College, specializing in injury prevention. “Is it because they have never been taught? Or is it because they have so many other issues on their plate they can’t even think about it?”

What’s more, this higher rate of injury does not take into account unreported injuries or patients who may not be identified as homeless. “We don’t know the real numbers of injuries because if you fall down, but you look relatively good, no one is going to report it,” explains Susan Fliesher, a pediatric nurse practitioner and assistant professor of nursing at Goldfarb School of Nursing at Barnes Jewish College. “Plus, you’re probably worried someone is going to take away your kid if they have injuries that look like you were negligent.”

While it is unknown what the true incidence of unintentional injury among homeless children is, with a staggering 2.5 million children in the United States experiencing homelessness, the prevention of injuries in this targeted population is critical.

Many mothers were never taught how to identify safety hazards like the one above, but studies show a positive relationship between child safety education and a decrease in injuries. For low-income families, home visits have proved an effective way to provide this education.

An Innovative Program

Studies have shown a positive relationship between child safety hazard education and a decrease in childhood injuries. One study reviewed parent education programs and reported fewer injuries in children of families who had received safety hazard education training. It concluded that interventions largely associated with home visits provided to disadvantaged families are effective in reducing unintentional injuries in children and improving home safety in this population. But how do you provide a home visit when the family is homeless?

Curtis and Fliesher found a solution: bring the home to them.

After seeing what she calls a “revolving door” of children coming into the emergency room with injuries that could have been prevented, Curtis knew something had to be done. “What we really noticed is that these mothers have not been taught how to identify hazards to prevent injuries from ever happening,” says Curtis. “We decided they had to be taught. It’s a skill and it’s not intuitive to many of these mothers.”

“A lot of mothers don’t realize they need to have the attention to the children that they do,” Fliesher adds. “If you haven’t had much experience, you don’t think about that safety until someone gets hurt.”

Curtis went down to the Goodwill and bought items that she had seen cause injuries to children coming into the emergency room—curling irons, marbles, etc. Piling all the items into a plastic rolling cart, she began working with women in poverty who were suffering from substance abuse issues. Getting the cart in and out of her car and to the facility proved difficult however.

Then she found the answer: “I was walking between buildings on campus and found an old College of Nursing van.” The old Winnebago had sat idle for years. “It had flat tires and it was ugly,” explains Curtis. Funded by the college of nursing research faculty grant program, the van was retrofitted to look like a home environment and outfitted with the simulated hazards.

Some of the safety hazards that were placed in the van included: electrical outlets not covered, frayed electrical cords, coffee cup on the edge of the table, space heater next to flammable material, cigarette lighter on end table, TV in position to tip over, poison cleaning agents under sink, hot plate on edge of counter, bucket of water, button batteries on a side table, beads on table (not a safe toy), medication bottle on coffee table, smoke detector without batteries, older crib with rails that were too wide, stuffed animals in the crib, and pans on the stove with the handles turned outward that a small child could easily reach.

Mary Curtis refitted a van to look like a home environment and outfitted it with various simulated safety hazards.

Working with Homeless Mothers

Fliesher adapted the program to work with mothers experiencing homelessness for her scholarly project as part of her Doctorate of Nursing Practice, a clinical doctorate for nursing. The van was parked outside a shelter for homeless mothers, who were invited to participate in the program. Participants then boarded the van and were asked to identify the various child safety hazards they noticed. The van had several areas with intentionally placed safety hazards that might be seen in any living room, kitchen, dining room, or bedroom. A checklist was used and a check was made when a mother verbalized seeing a safety hazard.

Following the initial van experience, a class was provided for mothers to talk about safety hazards that could be dangerous for their children. “This enables people to have some time where you can really dig into ‘What’s my child like? Why would he be at more risk for this? What makes it easy for a child to get hurt?” explains Fliesher.

Laminated pictures of safety hazards were shown and passed around. They talked about the age at which a child might have an increased risk from the safety hazards in each picture, discussed how children develop, and examined the risks at different stages. “You really have to know your own child,” clarifies Fliesher. “All three year olds are not the same. Some are more prone to danger than others. It depends on the temperament of the child.”

There were also discussions about the severity of the injuries and whether moms thought their child(ren) might be at risk. According to Fliesher, “If you perceive that there is a risk, that it’s a severe risk, and that there might be something you can do to prevent it, you’re more likely to do it if there aren’t a lot of barriers.”

Participants were encouraged to tell stories about their experience with childhood injuries to make the discussion more real. One mother spoke about her child’s burn on his hand after touching an electric stove burner that was turned off, but was still hot. She did not think he was tall enough to do that or that he would want to touch that surface. Another mom spoke of her child falling off the bed when she did not think the infant could roll. “Giving the mothers time to verbalize is the most essential aspect for success,” says Curtis. “Giving them the time to share stories with each other … I think a lot of them have some guilt around these injuries and it helps them process through that. They also learn from each other.”

When moms were asked about making changes in the environment or in supervision to prevent injuries, they were able to talk about what they might be willing to do differently. “You see why some people will do different health behaviors and others won’t,” describes Fliesher. “It makes a lot of sense that if you don’t perceive something is much of a risk, or that you’re at risk for it, you’re not going to do it.”

When speaking about what is required to make the environment safer, it was important to discuss the fact that homeless families are in a unique position, often staying with others, with less control over their environment. They talked about ways to advocate for making changes if they thought something was unsafe. If they were unable to get changes made, they discussed other options. “This empowers people to be an advocate for their children,” Fliesher continues. “To provide more supervision and to have the self-confidence to say this isn’t right and I have to do something about it.” When mothers were asked if they would they feel comfortable asking others to make environmental changes regarding safety hazards, sixteen out of seventeen mothers said they would. The mother who said she wouldn’t feel comfortable explained that while it wasn’t her place, she would “watch out more.”

Upon completion of the class, the mothers returned to the van and were found to identify a statistically significant increase in the number of safety hazards in the van, with scores improving by 23.9%. That shows a real improvement in women’s ability to identify safety hazards after child safety hazard education.

Mothers who participated in the program boarded the van and pointed out the hazards they noticed. The group then attended a class, discussing topics such as different types of hazards, the levels of severity of various injuries, and if they thought their child was at risk.

The Value of Safety Hazard Identification on a Mobile Van

What is the value of using a mobile van refitted for safety hazard education? Beyond the added ease of transporting simulated hazards, the van offered the ability to provide what is essentially a home visit.

Using a van also added a layer of excitement to the program. There was a lot of curiosity regarding the large van and the mothers were intrigued to be able to see what was in it. It made the education come to life. “It really gives you the idea that there’s so much more out there in terms of how you present that material that brings it to life—especially if you bring it to someone’s location,” says Fliesher.

Participants enjoyed climbing onto the van to see what was there. “Looking for safety hazards in the van reminds me of the book, Where’s Waldo?” explained one mom who thought it was fun to try to find the safety hazards. When the mothers went back onto the van for the second time, they were excited to find new hazards and wanted to know what they had missed. “The women enjoyed going into a space that was set up with safety hazards and having the challenge of finding them,” says the program director at the agency where the study was done. “They thought it was fun. Going and finding things that were a problem reinforced the need to evaluate an environment in order to make it safer for their children.”

“Now that we have the van set up—it’s mobile, it’s ready to go—we can take it wherever,” says Curtis. “So now we get invited to certain events like a health fair where we can walk people through and teach them on the spot.”

While the van is a great way to show safety hazards, the initial cost plus maintenance and insurance may be impractical for agencies with limited finances. Alternatively, service providers could set up a room with a traveling pack of child safety hazards, create a diorama with several rooms that could be taken from place to place, or simply use pictures with hazards that participants can circle.

“The bottom line is that we have to be creative in the ways that we teach people,” explains Fliesher. “Not everybody learns the same way. Practical application is the best when it comes to learning. You can talk about safety hazards and see that they get it and can apply it in real time.”

After the safety hazard education class, participants returned to the van to look for hazards they initially missed. For example, some participants may not have realized that a hot coffee pot or a pan could be within reach of a small child, but after discussing this type of hazard in class, it was easy to spot.

Conclusions

Some parents believe injuries are just a natural part of childhood—children will learn from getting injured and will avoid similar risks in the future. “The idea of the class was if you can change their perception, then they are more willing to say ‘I really need to think about this because this could be a serious injury,’” says Fliesher. “If they think it’s a ‘no-big-deal’ injury, it might not be worth it to them.” In other words, parents are more likely to adopt preventive behaviors to protect their child against injury when they perceive their child as vulnerable to a severe injury.

Less than half of the women recalled having any previous child safety hazard education. This may be due to time constraints in a busy primary care pediatric setting, with limited time to discuss topics more in depth, distractions, or too much information to absorb in such a short time. Regardless of why the mothers said they had not previously received the child safety hazard education, it is clear there is a need for more education to be offered outside of the primary care setting to homeless women whose children are at increased risk for unintentional injury.

“The beauty of this is that it doesn’t have to be a nurse that does it,” explains Fliesher. “There are a lot of professionals out there who are working with the homeless and people who are lower-income, who want to be excellent parents and just do not have the support. These professionals know a lot about safety hazards and development. They can provide wonderful education with this.”

Upon completion of the experience, the mothers who participated in the study were asked whether they found the class helpful. Many expressed that they learned a lot gained a sense of accomplishment from the class. One participant expressed, “There is a lot I didn’t know about safety.” Another mom asked for additional child safety hazard education to learn more about outdoor issues, while a different mother said she would like to learn other topics with this kind of format.

Like most parents, the mothers wanted the best for their children. According to Fliesher, “They wanted to learn. If you’re not paternalistic when you teach, but instead involve them and ask them ‘What do you think? What would you do? What would make you want to do this and what would make you not do it?’ that gives them some control. I think in life people sometimes don’t have a lot of control, so it’s neat to be able to say ‘I can do this.’”

Innovative methods of safety hazard education need to be developed to support and empower parents with and without homes to provide a safer environment for their children. “I think to really connect with people,” Fliesher adds, “they need to be able to apply it to real life. They need to see it and know that ‘Yes, that’s a problem.’” Developing a culture of safety will require those working with children and families in poverty to become more informed about childhood injury and to partner with parents, families, colleagues, and communities to create the changes needed to prevent childhood injury.

References

Centers for Disease Control. (2012). National Center for Injury Prevention and Control of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/safechild/pdf/ ■ Frencher, S. K., Benedicto, C. M., Kendig, T. D., Herman, D., Barlow, B., & Pressley, J. C. (2010). A comparative analysis of serious injury and illness among homeless and housed low income residents of New York City. The Journal of Trauma- Injury, Infection, and Critical Care, 69, S191-S199. ■ Garzon, Dawn. (2005). Contributing factors to preschool unintentional Injury. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 20, 441-447. ■ Garzon, D. L., Lee, R. K., & Homan, S. M. (2007). There’s no place like home: A preliminary study of toddler unintentional injury. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 22(5), 368-375 ■ Ingrim, J., & Emond, A. (2009). Parents’ perceptions of home injury risk and attitudes to supervision on pre-school children: A qualitative study in economically deprived communities. Primary Health Care Research & Development, 10, 98-108 ■ Kendrick, D., Barlow, J., Hampshire, A., Polnay, L., & Stewart-Brown, S. (2007). Parenting interventions for the prevention of unintentional injuries in childhood. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 4, 1-33. doi: 101002/14651858.CD006020.pu ■ Kendrick, D., Mulvaney, C. A., Ye, L., Stevens, T., Mytton, J. A., & Stewart-Brown, S. (2013). Parenting interventions for the prevention of unintentional injuries in childhood. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 3. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006020.pub3 ■ Morrongiello, B.A. & Dayler, L. (1996). A community-based study of parents’ knowledge, attitudes and beliefs related to childhood injuries. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 87, 383-388. ■ Morrongiello, B.A., & Kiriakou, S. (2004). Mothers’ home-safety practices for preventing six types of childhood injuries: What they do, and why? Journal of Pediatric to Psychology, 29, 285-297. ■ Morrongiello, B.A., Midgett, C., & Shields, R. (2001). Don’t run with scissors: Young children’s knowledge of home safety rules. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 26, 105-115. ■ Morrongiello, B.A., Ondejko, L., & Littejohn, B. A. (2004). Understanding toddlers’ in home injuries: II. Examining parental strategies, and their efficacy, for managing child injury risk. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 29, 433-446. doi: 10:1093/jpepsy/jso47 ■ National_Action_Plan_for_Child_Injury_Prevention.pdfmaq and https://www.cdc.gov/safechild/NAP/background.html (n.d.). ■ The National Center on Family Homelessness. (2017). Retrieved from website http://www.air.org/search/site/child%20homelessness%20statistics ■ Rosenstock, I. (2005). Why people use health services. The Milbank Quarterly, 83, 1-32. Reprinted from The Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly, 44, 94-124 ■ Russell, K. M., & Champion, V. L. (1996). Health beliefs and social influence in home safety practices of mothers with preschool children. Image: Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 28(1), 59-64 ■ Saluja, G.,Brenner, R., Morrongiello, B. A., Haynie, D., Rivera, M, & Cheng, T. L. (2003). The role of supervision in child injury risk: Definition, conceptual and measurement issues. Injury Control and Safety Promotion, 11, 17-22 ■ Schwebel, D.C. & J. Gaines. (2007). Pediatric unintentional injury: Behavioral risk factors and implications for prevention. Journal of Developmental Pediatrics, 28(3), 245-254.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

Sheltered from the Storm: A Shelter-Based Program for Treating Opioid Addiction

by Mari Rich

It’s hard to pick up a newspaper or magazine lately that does not have some dire coverage about the epidemic of opioid abuse raging across the country, from large urban centers to rural hamlets that might once have been described as bucolic. Officials from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimate that more than 90 Americans die each day from an opioid overdose.

While substance abuse affects those of every age, gender, ethnicity, and socioeconomic group, the problem impacts the nation’s homeless population in a particularly disproportionate way; according to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), one in five people experiencing homelessness has a chronic substance use disorder.

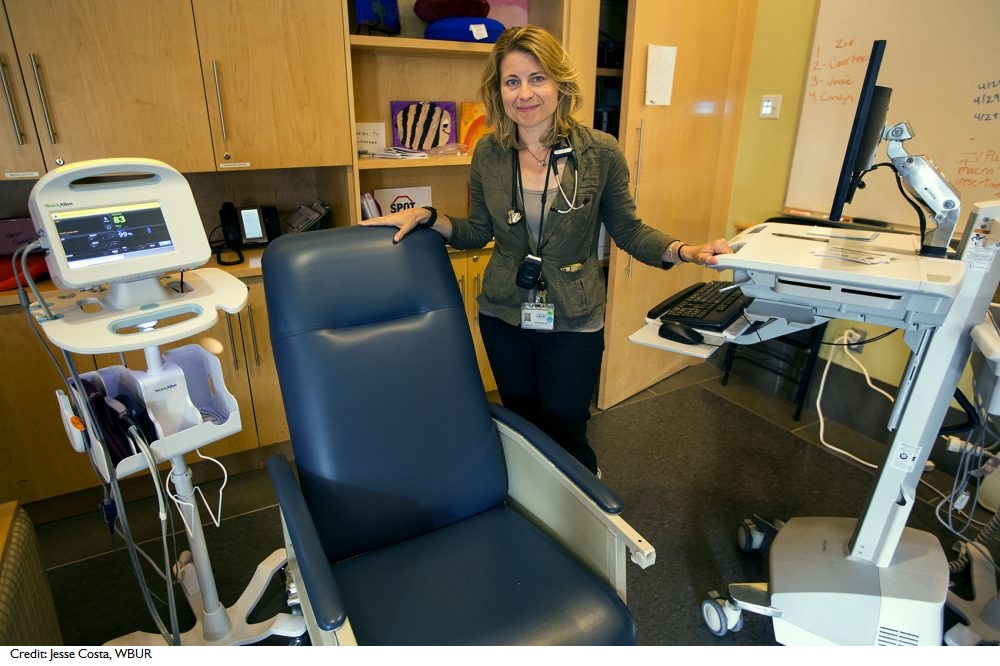

An innovative program by Boston Health Care for the Homeless Program (BHCHP) conducted on-site at a family shelter in Waltham, MA is aimed at treating those with barriers to accessing traditional office-based opioid treatments.

Boston Health Care for the Homeless Program medical director Jessie Gaeta spearheaded the development of SPOT, or Supportive Place for Observation and Treatment, a Boston drop-in center for those in need of a safe place to come after using (see sidebar). Photo Credit: Jesse Costa, WBUR

The Road to Addiction

In a study conducted of some 30,000 patients who had received care from BHCHP over a five-year period, researchers discovered that drug overdose had replaced HIV as the leading cause of death among the homeless in that city—and that prescription opioids and heroin were involved in more than 80 percent of those overdoses. People aged 25-44 experiencing homelessness were an astonishing nine times more likely to die from an overdose than their stably housed counterparts, and in one United States Conference of Mayors survey on hunger and homelessness, many cities reported that substance abuse was one of the top causes of family homelessness.

The numbers, while horrifying, are abstractions to most of us. Tracey Kinsman, a 38-year-old mother of six, can all too easily put a personal face on those harsh statistics, however. “It’s not unusual for me to log onto Facebook and find out that another one of my friends has ODed,” she says. Kinsman, who lives with three of her children and her fiancé in a family shelter outside of Boston, has overdosed twice herself. “You can boost the high you get from injecting heroin by taking another drug like Xanax, but it’s really hard to get the proportions right,” she explains. “That’s what happened to me. The first time I ODed, I took a half of a Xanax and shot up a while later. I remember falling face-first onto the bed right after shooting up, and then the next thing I remember was waking up in a cold shower with my ex standing over me. If he hadn’t been there I would probably have died. He told me I had turned totally blue.” (Heroin, when combined with central nervous system depressants like Xanax, Valium, or Ativan—a class of drugs known as benzodiazepines—can cause a user to slip gradually into unconsciousness, followed by coma, and, if they are not discovered in time, ultimately death.)

Kinsman has abstained from illicit opioid use for three years now. Before landing on the floor of that cold, life-saving shower, she had traveled a tortuous road that included being molested by her mother’s boyfriend and becoming entangled in a physically and emotionally abusive relationship with the man who is now her ex. One night, when she was in her mid-20s, she was attacked on the street, with her assailants viciously pummeling her and yanking large sections of hair from her scalp. In pain, she readily accepted the Percocet and Vicodin that her mother, who purported to suffer from a bad back, had procured via a legal prescription from a less-than-scrupulous doctor.

Kinsman soon began visiting the doctor herself, filling prescriptions of her own for the highly addictive painkillers. It was not until four years later, when she became pregnant with her third child, that the physician began refusing to pull out his prescription pad. Undergoing abrupt withdrawal, she was receptive when an acquaintance told her that cheap, easily obtainable heroin would closely mimic the effects of her prescription opioids. She was far from alone; one recent report found that four in five new heroin users started out by misusing prescription painkillers and that of those in treatment, 94 percent had made that leap because prescription opioids were pricier and harder to get.

Kinsman’s subsequent journey found her selling herself on the street to obtain drugs; watching her mother and ex also descend into heroin addiction; doing four months in prison for possession and intent to sell; and being the subject of multiple reports of suspected child neglect and abuse. While she often dreamed of getting clean, that goal seemed far out of reach, especially with her then-husband insisting they get high together and her mother regularly demanding that Kinsman help her shoot up.

At SPOT, users can ride out their high while being monitored by a nurse for overdose and later counseled about addiction-treatment options.

An Uphill Climb to Recovery

It was thus something of a step in the right direction for her when Kinsman’s husband left one day in 2014, and she went on Facebook to announce her newly single status. Much to her surprise she heard from her childhood sweetheart, Dave Ford, an aspiring chef who was then living not far away in New Hampshire. “Dave paid someone to come get me and drive me to New Hampshire to try to get clean,” she recalls. “He has been by my side ever since.”

Even with Ford’s steadfast support, the process of weaning herself from heroin was arduous. With his help, she began weekly Medication-Assisted Treatment (MAT)—the use of medications in combination with counseling to treat substance use disorders—but reaching the New Hampshire clinic he had found for her required a bus ride of more than an hour each week from her mother’s home in Massachusetts and lengthy periods in unpleasant waiting rooms, where it was not uncommon to see fights breaking out among frustrated, strung-out, or just plain combative clients. “We had to take my youngest, Nevaeh, along, and it was terrible to be bringing her into that environment,” Kinsman recalls. Still, determined to kick her addiction, she persevered despite those difficulties.

Just as her husband’s abandonment ultimately turned into something of a blessing in disguise, so, too, did the next upheaval she suffered. By 2015 Ford and the children who remained in Kinsman’s custody had all moved in with her and her mother, but when the home became unlivable and overrun with roaches and bedbugs, they were forced to enter the shelter system.

Dedicated to MAT and her new-found sobriety, Kinsman was grateful to discover that the family shelter to which they were assigned was home to an innovative program called Shelter-Based Opioid Treatment (SBOT).

Surmountable Barriers

In mid-2015, a group from BHCHP, including Harvard-trained physicians Avik Chatterjee and Aura Obando, created the state’s first SBOT program at a 120-room motel-shelter housing family groups in Waltham, a city just outside of Boston. Aimed at treating those who had barriers to accessing traditional office-based opioid treatments, the program was staffed by a physician, a nurse (who would handle the day-to-day tasks of handing out meds and getting urine samples), two case managers, and a behavioral health practitioner. The group found their services in immediate demand; an estimated 6% of the facility’s adult residents were suffering from opioid use disorder.

As Suzanne Zerger of the National Health Care for the Homeless Council wrote in her comprehensive paper “Substance Abuse Treatment: What Works for Homeless People?”: “The relationship between chemical dependence and homelessness is interactive; one condition does not necessarily cause the other, but each can exacerbate problems associated with the other. Substance abuse can be both a precipitating factor and a consequence of homelessness.”

Experts now realize that many of the factors leading to homelessness also contribute to the development of addiction—untreated mental-health problems, physical or sexual abuse, lack of social supports, and insufficient resources to meet basic human needs, among them. In a cyclical chicken-and-egg situation, those experiencing homelessness often lack access to safe, clean locations in which to use their drugs of choice, and as a result they engage in rushed and risky drug-taking behaviors. Similarly, homelessness makes it difficult for them to adhere to the regular, long-term treatment plans required to manage the chronic health problems that often accompany substance abuse, including HIV and soft-tissue infection.

In the course of their work, Chatterjee and his colleagues frequently met patients experiencing the wide variety of consequences associated with the abuse of opioids, including the loss of child custody, an inability to maintain gainful employment, and the aforementioned physical comorbidities. (Young women and their children—the major constituents of families experiencing homelessness—face especially devastating health consequences of opioid use, with both neonatal abstinence syndrome and hepatitis C among women of child-bearing age on the rise, according to Chatterjee.)

In a paper recently published in the American Journal of Public Health, Chatterjee explains that the barriers to office-based opioid treatment (OBOT) for the homeless go far beyond the sometimes-lengthy bus rides and unpleasant conditions Kinsman described. These include other patient-based issues, such as the stigma many associate with frequenting a public clinic and the competing priorities (including finding work and obtaining sufficient healthy food) faced by those navigating homelessness along with opioid use disorder; the fact that there are relatively few providers licensed to prescribe buprenorphine and other opioid antagonists (see sidebar); and system-level issues, such as restrictions on how many patients each physician can treat.

He points out that families experiencing homelessness, who comprise more than one-third of his city’s homeless population, have additional barriers to treatment that homeless adults without dependents do not face. Unlike Kinsman, who had her fiancé to keep Nevaeh safe in the waiting room until her medication was dispensed, many have no safe, reliable source of childcare. Additionally, with family shelters often situated in out-of-the-way areas, some are physically unable or simply unwilling to undertake the grueling journey by public transportation to an OBOT location.

Dispensing opioid treatment drugs onsite, within a clinic set up at the shelter, greatly decreased those barriers. Transportation and childcare concerns were alleviated, and the intensive case management that was a key component of the program helped families cope with competing priorities. Additionally, the behavioral clinician on staff helped patients address any comorbid mental-health conditions they exhibited, and if the team believed a patient needed resources beyond the scope of the SBOT program, those were found and referrals made.

Case manager Maria Peguero cautions that operating an SBOT comes with its own set of issues, including some loss of privacy for clients, whose fellow residents can be judgemental initially. “Still, once people get to know one another and realize what a good thing it is that someone is seeking treatment, they become happy that we’re here as a resource,” she says. “They begin to look out for one another and come to us for help if they see anyone struggling with their treatment plan or addiction.”

Dr. Avik Chattejee (left) created the first shelter-based opioid treatment program (SBOT) in Massachusetts, at a 120-room motel-shelter housing families outside of Boston. Tracey Kinsman (right) was grateful the family shelter she moved to offered SBOT.

A Small but Encouraging Study

Chattejee’s American Journal of Public Health article details a study he completed of 10 patients (all with concurrent diagnoses of chronic pain and anxiety) enrolled in the SBOT program that first year. He and his co-authors reviewed the charts of those who received buprenorphine prescriptions for at least three months (choosing that timeframe because a 12-week endpoint had been employed in previous peer-reviewed studies of buprenorphine). Participants had from one to five children, and half had a partner in the shelter. The Massachusetts Department of Children and Families was involved in the care of children in five families with parents previously accused of abuse or neglect.

The results were encouraging. While four had reported a history of overdose prior to SBOT, no overdoses were documented during the study period. Although nine of the 10 had unprescribed controlled substances in their systems upon initial evaluation, by the third month that number had dropped to just one, and by the final days of the study, three were employed, compared to just one at the start.

Chatterjee admits, however, that transitioning back into the community was a significant challenge to his patients—particularly when housing became available without sufficient notice, allowing too little time to devise a new treatment plan. While patients were provided with prescriptions for opioid antagonists until new providers could be found and scheduled, other vital components, like mental-health services and intense case management, were harder to come by outside of SBOT. Chatterjee believes that a team specifically tasked with transition care, including home visits, might mitigate those problems and prevent relapse.

“We demonstrated that SBOT is safe and feasible, and it definitely increases access to addiction treatment for vulnerable patients,” he says. “We have already launched SBOT at a second shelter and hope for it to be replicated widely by other groups.”

Kinsman would like to contribute to that mission one day. “I’m doing well on Suboxone, and I foresee a time when I won’t need MAT at all,” she says. “I hope to go back to school and become an addictions counselor. I truly believe that former addicts make the best counselors, because they’re the only ones who know what this struggle is really like.”

Understanding Opioid Use Disorder and Medication-Assisted Treatment

When opiates are introduced into the body, whether taken as prescribed or illicitly, they bind to and activate receptors in the brain responsible for regulating pain and feelings of well-being. Repeated use actually changes the physical structure and physiology of the brain, causing physical dependence. Opioid use disorder is clinically diagnosed when at least two criteria are met from a list that includes: opioids being taken in larger amounts or over a longer period than was intended; a persistent desire or unsuccessful efforts to cut down or control opioid use; large amounts of time spent in activities necessary to obtain the opioid, use the opioid, or recover from its effects; use resulting in a failure to fulfill major role obligations at work, school, or home; continued opioid use despite having persistent or recurrent social or interpersonal problems caused or exacerbated by their effects; recurrent opioid use in situations in which it is physically hazardous; a need for markedly increased amounts of opioids to achieve intoxication or desired effect.

Medication-assisted treatment helps to reduce withdrawal symptoms and ameliorate continuing cravings, thereby lowering the risk of relapse. Its length can vary, even being continued indefinitely if the patient is prone to regular relapse.

All medications used in MAT are approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and work to repair brain chemistry, block the mood-altering effects of opioids, and normalize body functions without the detrimental effects of the abused drug.

The most common prescribed medications include Naltrexone, an opioid antagonist, which means that it locks onto the opioid receptors in the brain and prevents the “high” typically experienced by those with opioid use disorder; Buprenorphine, a partial opioid agonist, which provides some of the same euphoric feelings the patient seeks; and Suboxone, which contains both buprenorphine and naloxone (an antagonist sold under the name Narcan to block the effects of opioids, especially in situations of overdose).

Laypeople may think most readily of Methadone, a long-acting opioid that is often mentioned in news coverage of the epidemic or in popular culture, but Chatterjee explains that his clinic is not deeply involved in its use. Methadone is itself addictive and typically requires daily visits—most often early in the morning when parents are readying their children for school. “If a patient told us that they are having trouble making it to their methadone appointments due to logistical barriers, we would probably consider helping them make the switch to buprenorphine instead,” he explains.

Although some of the same drugs have been proven to aid in treating addiction to alcohol, they are much more effective in treating opioid addiction. While they are welcome to access onsite individual and group therapy, clinic staffers typically direct those affected by alcoholism to the many Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) meetings available in the community.

The Best SPOT

In 2016, the Boston Health Care for the Homeless Program launched a new facility they dubbed the Supportive Place for Observation and Treatment (SPOT). Housed in a renovated conference room at their main building in the city’s South End, the drop-in space contains 10 reclining chairs in which those needing a safe alternative to the street can ride out their high while being monitored by nurses, prevented from overdosing, and, once they are no longer high, counseled about addiction-treatment options, if they are receptive.

In its first year of operation, SPOT personnel had logged more than 3,000 encounters with homeless patients (some of whom came multiple times). They calculate that a third of the visits would have resulted in a trip to the emergency room had SPOT not been in operation, and that ten percent of their visitors went into treatment immediately afterwards.

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention ■ Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration ■ Boston Health Care for the Homeless Program ■ Baggett TP, Hwang SW, O’Connell JJ, Porneala BC, Stringfellow EJ, Orav EJ, Singer DE, Rigotti NA. Mortality Among Homeless Adults in BostonShifts in Causes of Death Over a 15-Year Period. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(3):189–195. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.1604 ■ United States Conference of Mayors ■ Meges D, Zevin B, Cookson E, Bascelli L, Denning P, Little J, Doe-Simkins M, Wheeler E, Watlov Phillips S, Bhalla P, Nance M, Cobb G, Tankanow J, Williamson J, Post P (Ed.). Adapting Your Practice: Recommendations for the Care of Homeless Patients with Opioid Use Disorders. 102 pages. Nashville: Health Care for the Homeless Clinicians’ Network, National Health Care for the Homeless Council, Inc., 2014. ■ Avik Chatterjee et al. “Shelter-Based Opioid Treatment: Increasing Access to Addiction Treatment in a Family Shelter”, American Journal of Public Health 107, no. 7 (July 1, 2017): pp. 1092-1094. ■ National Health Care for the Homeless Council. (May 2016.) Medication-assisted Treatment: Buprenorphine in the HCH Community. (Authors: Matt Warfield, National Health Policy Organizer, and Barbara DiPietro, Senior Director of Policy.) Available at: https://www.nhchc.org/policy-advocacy/reform/nhchc-health-reform-materials/.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

Play, Art, Caring: Creating Emotionally Healthy Homeless Families

by Lee Erica Elder

A lack of stability. Frequent moves. Disrupted education. Feeling unsafe. Separation from loved ones. Exposure to violence and substance abuse. Homeless children face an inordinate amount of stress and anxiety in their day-to-day lives, and as a result, are more likely to experience problems with their emotional well-being and mental health.

Throughout the country, there are organizations committed to mental health and stress-reduction for children, parents, and families experiencing homelessness or housing insecurity. They use holistic approaches to wellness and focus on assessing clients as individuals. Care is based on distinct needs rather than a one-size-fits-all solution. Whether through trauma-informed care, expressive tools and treatments, or creative modalities, they are working to heal their communities.

The work is crucial. A recent study found that homeless high school students in New York City faced higher rates of depression and were over three times more likely to attempt suicide than their housed peers. Not only are they more likely to attempt suicide, they do so more often and more seriously (requiring medical attention) than housed teens.

Homelessness is traumatic for children and can result in a behavioral shift. Barbara Schwartz, director of the GREAT Youth and Families Program of the Housing Families organization in Malden, MA, emphasizes looking for the meaning behind a child’s behavior. For example, a child who is acting out may be a hurting child. The GREAT Youth and Families Program provides arts and expressive therapy to address the social and emotional needs of children who have experienced significant trauma.

Building Truly Caring Systems

Caregivers stress the need for systems of care rather than discrete solutions. This specialized work is engaging, encouraging, and humanizing. “We are all complex creatures,” says Jill Wiedemann-West, CEO of People Incorporated Mental Health Services in St. Paul, MN, which provides community mental health services, in-school and in-clinic resources for children and families, and homeless outreach for adults. “Add to that the potential of homelessness, mental illness, or chemical health issues, family issues, or trauma—it amps up the need for us to recognize the dynamic nature of the population.”

The caring system philosophy reaches back more than forty years. The impetus was a need that Pastor Harry Maghakian saw in 1969, when veterans who hung around his church had nowhere else to go. He opened up the basement doors for refreshments and fellowship, in what would become a legacy of outreach. “He just thought maybe they needed a sense of community and a hot cup of coffee,” says Wiedemann-West. “Ultimately it was the roots of what People Incorporated grew into as an agency. We look at ways that as a community mental health provider, we can continue to look at the gaps that exist in our communities and try to fill those,” she says.

From sharing a cup of coffee and conversation with a stressed-out parent, to making children feel safe enough to participate in childlike activities, seemingly small interventions are layered for a powerful impact on homelessness, building hope, and an opening for more progress.

The caring system is effective in Boston, MA. “We try to look at the constellation of services that best match families’ needs without overwhelming them,” says Linda Smith, manager of behavioral health services for the family team at Boston Health Care for the Homeless Program (BHCHP.) BHCHP’s family team delivers outreach services at shelters and motels throughout the area. Families have access to individual and group therapy, with family, couple, or sibling sessions as needed. “We tailor the intervention to the needs of the family based on assessment,” says Smith. BHCHP runs clinics in downtown Boston shelters, as well as hospital and walk-in clinics, and their behavioral health team gives medication assistance to those struggling with opioid addiction (See Sheltering the Storm). With these resources, they are able to service 11,00o people per year.

An essential part of creating a caring system is to take a trauma-informed approach to care. The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) defines a trauma-informed approach as one that “realizes the widespread impact of trauma and understands potential paths for recovery; recognizes the signs and symptoms of trauma in clients, families, staff, and others involved with the system; responds by fully integrating knowledge about trauma into policies, procedures, and practices; and seeks to actively resist re-traumatization.”

In Washington D.C., The Homeless Children’s Playtime Project (HCPP) facilitates trauma-informed play for children aged six months to 18 years-old. Trauma-informed play focuses on providing a consistent, safe place for children to explore and grow. This regularity and consistency goes a long way toward giving the children a sense of stability. During trauma-informed play, children get to make choices about how they want to spend their time, giving them a sense of power over their world. Clear expectations and boundaries are set and children are told what will come next, building a feeling of emotional and physical safety for children who have experienced neither.

HCPP was founded in 2003 by social worker and child advocate Jamila Larson and lawyer Regina “Gina” Kline. The first iteration was a playroom with weekly activities and snacks in the Community for Creative Nonviolence (CCNV) shelter. “The vast majority of family shelters had no programs or services for children despite the myriad risk factors associated with homelessness,” says communications coordinator Melanie Hatter. “We currently serve four sites across the District: Turning Point, DASH Cornerstone Transitional Living Program, D.C. General, and the Quality Inn motel overflow shelter.”

Lakia Barnett, an HCPP parent, found relief in these resources. “I have two kids with learning disabilities, and it was really hard,” she says. “One of my sons didn’t like to be social, but when he got to Playtime, he opened up so much. It [Playtime] helped my family, because it gave me that breath to relieve myself from whatever I was going through at that time, and for other mothers there; it’s a lot of pressure trying to keep things normal in an atmosphere like that when you’re used to being in your own home…Playtime has been very much a help to me in my fragile time.”

The Homeless Children’s Playtime Project (HCPP) provides a safe place for children to explore and grow through the use of trauma-informed play. As they play at the Turning Point facility (shown here), clear expectations and boundaries are set, building a feeling of emotional and physical safety.

Barriers to Mental Health and Wellness

Co-occurring conditions are a major barrier that must be addressed for effective interventions. Wiedemann-West from People Incorporated estimates that more than 60 percent of patients presenting primarily with mental health needs have unaddressed physical issues, as well. “The clients we serve are complex—besides mental illness or homelessness, they have health, dental, and housing needs,” she says.

Children have their own considerations in mental health assessments. “It is important to start seeing children as a special population of individuals experiencing homelessness worthy of their own intervention,” says Hatter of HCPP. “Creating trauma-informed shelter environments requires a significant culture-shift. It’s important to offer integrated medical and behavioral healthcare, developmental assessments, parenting education and supports, and family-oriented developmental supports like play groups.”

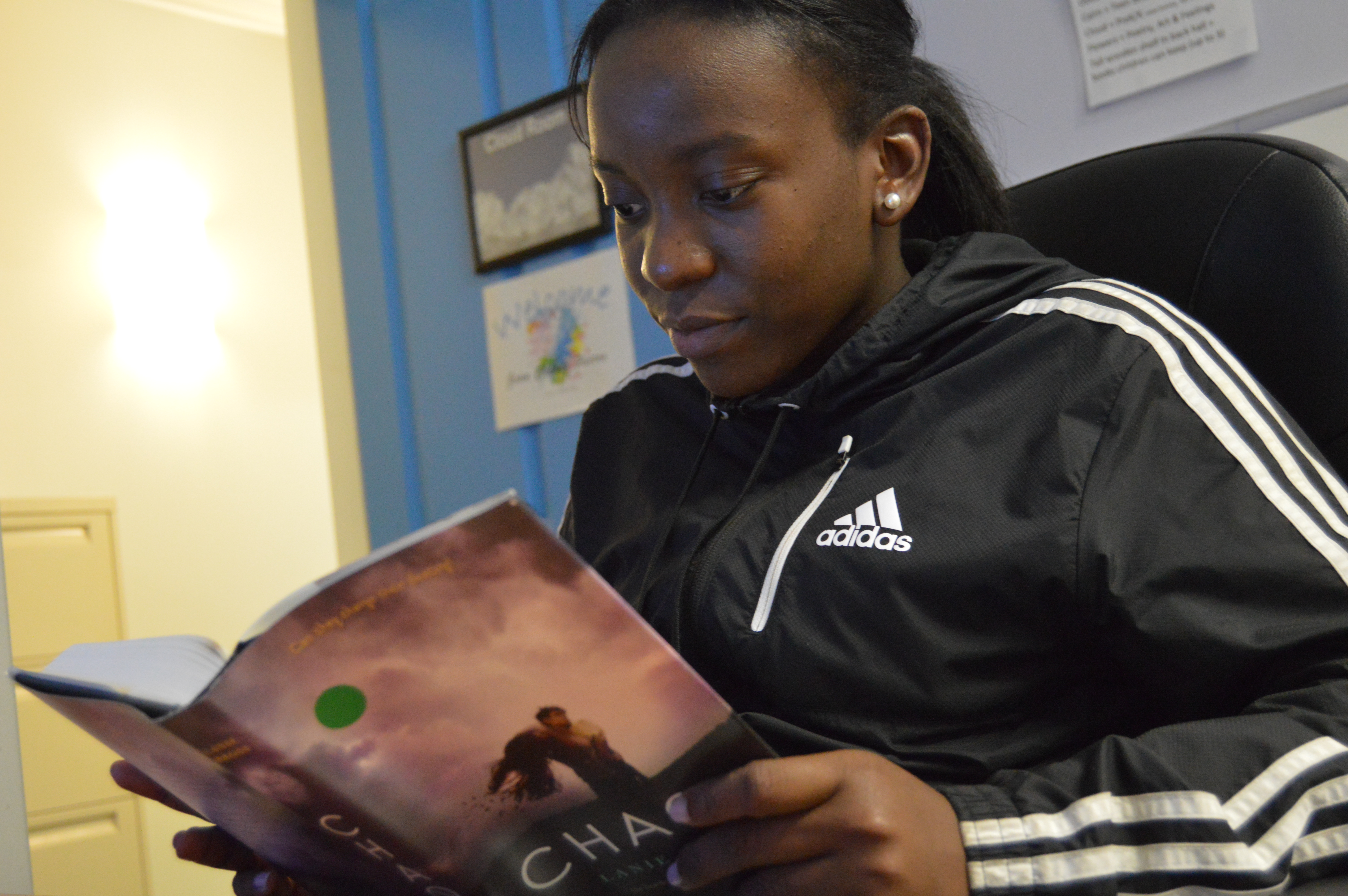

At Completely KIDS, in Omaha, Nebraska, the goal is to increase access to behavioral and mental health services for low-income students. A shelter program is a fundamental component of the organization’s mission. In 2016, 89 homeless youths received afterschool services through this programming, per Bill Heaston, program manager. “Throughout the year, it became evident that a greater focus on the social-emotional support of the children was needed,” he says. “The trauma of homelessness can be scary, lonely, and hard to articulate. Our shelter program seeks to provide a sense of security and comfort amidst the waves of hopelessness.” Free, on-site behavioral health therapy means access to services that would take weeks or months to obtain otherwise, and alleviates transportation barriers. Psycho-educational skills groups are available at various after school programs, and focus on social, emotional, and behavioral skills such as self-regulation, positive self-esteem, and stress reduction.

Parental engagement is key to bridging barriers. “Completely KIDS strongly values parental inclusion and involvement in healthy youth development,” says family program manager Beatriz Gonzalez. “The behavioral health therapists facilitate the Strengthening Families Parenting Program each semester,” she says. The ten-week program covers parenting skills, positive relationships, increasing family resiliency, and stress reduction. Families meet weekly for two-hour sessions where they learn, practice, and discuss skills, and share a meal.

Hatter from HCPP stresses the need to support parents navigating difficult systems. “Since most family shelters are far from ‘service-rich’ environments for families, motivating parents to access the often bureaucratic and under-resourced mental health system outside of the shelter is challenging,” she says. “The stigma of treating a mental health condition, transportation, insurance barriers, and the energy that it takes to face painful issues often requires superhuman strength that can be difficult for parents in crisis to summon.” HCCP’s evidence-based parenting course helps reduce stress and introduces critical communication techniques.

Entrenched stigma, trauma, and prolonged loss accompany homelessness. “I’ve been around long enough that I’ve seen intergenerational homelessness,” says Smith, who has worked at BHCHP for 20 years and practiced counseling for thirty. “At the shelter end, there are other kinds of things that go along with the experience of homelessness—you lose your home, then you’re moving and living with all these people that you don’t know. You often have to change schools, you lose your pets, you lose your toys, sometimes your pediatrician. So many losses—that’s very difficult.”

Shame is a huge barrier to receiving treatment. “The families feel ashamed and blame themselves,” says Barbara Schwartz, director of the GREAT Youth and Families Program of the Housing Families organization in Malden, MA. “Healing takes a long time. What looks like a bad or acting out child, is a hurting child. What looks like a shut down child is a scared child. What looks like a kid who isn’t trying might be someone who is emotionally overwhelmed. Look for the meaning of the behavior and assume the best of the child and you’ll have more success,” she says. Housing Families offers children—preschool aged through teens—counseling and therapeutic groups. “We also offer parent counseling, parenting groups, raising a reader, yoga and relaxation, and men’s and women’s therapy groups,” says Schwartz.

People Incorporated Mental Health Services in St. Paul, MN provides community mental health services, in-school and in-clinic resources for children and families, and homeless outreach for adults. Their Artability class, shown here, is a painting class open to anyone with mental illness, not just clients.

Healing Trauma Through Art

Part of looking at the whole person is using modalities that facilitate connection. This is essential for children who don’t have the language adults do to express feelings. Creative outlets cultivate positive experiences, making relationship dynamics more fluid and empathetic. “With children in particular we find that utilizing expressive arts is an easy way to tap into what’s going on with them and for us to help them express it,” says Smith from BHCHP. A board certified and registered art therapist, she’s rarely without a bag of puppets and toys and uses dance and music play. She recalls a mother-daughter relationship transformed by creativity. They lived in a shelter and mom was a legally blind domestic violence victim. She’d stopped attending individual therapy, so Smith tried the family route. “I shifted my work to pull mom into gaining empathy around the child’s issues because mom was kind of stuck in her own. When we cultivated the wonderful expressive side of the child, through dancing, sculpture, and singing, mom became involved and grew to appreciate her child in a different way. This created a stronger bond between the two of them and helped validate the child.”

HCPP staff is trained to infuse therapeutic principles into healing play. “Sometimes we might notice a child playing ‘eviction’ with a dollhouse or acting out a domestic violence scene,” says Hatter. “We are able to follow-up with parents who might not be aware of what their children are struggling with and provide necessary referrals or support. We offer yoga, art projects, and fun opportunities for expression and physical exercise critical for stress reduction and promoting healthy child development,” she says. Here’s a portion of a speech from a participant whose behavior was positively impacted by the program:

My name is “Carly.” I just turned fifteen years old last week. I currently live at DC General and I’ve lived there off and on since I was seven years old. Living at DC General is very stressful and complicated but I know God has a big surprise for me one day. I never planned to live this way but I have no control over things that come into my life. I do have control over how I choose to handle those situations and I try my best to stay calm and respectful.

Our rooms are nothing like the homes you have and the only fun we get to have is when we go to playtime. The teen night volunteers brighten up our days! They care about teens like us. They help us get through very hard situations, literally! Thanks to my family who does the best they can, thanks to the volunteers and playtime for taking the time out to be there for all of us.

Homeless children have their own considerations when it comes to mental health and therefore need their own unique homelessness interventions, such as the trauma-informed play groups at the Homeless Children’s Playtime Project (HCPP) in Washington, DC.

Free Arts in Los Angeles is boosting self-worth and reducing stress for more than 22,000 youth. They offer a variety of art programs for children experiencing homelessness or living in transitional housing. Their courthouse program provides a supportive arts space and distraction for kids during morning and afternoon court sessions, five days a week, servicing up to sixty children per day. The volunteer mentorship program, which works in eight-week sessions, relies on art to break down walls built by trauma and other stressors. “We do art with intention,” says programs manager Karol Hernandez. Every project has an empowering theme. Afterwards, mentors debrief the kids and ask stimulating questions about the art.

Hernandez worked with a young boy named King, about five or six years old, who was staying in an area where a body was discovered. For a dream catcher art project, the children were told to draw a favorite dream. King confided that he only had nightmares. She asked him to imagine a good dream and shared one of hers—featuring cotton candy clouds and gumball grass. He was inspired and agreed to try. A volunteer helped him step-by-step—putting on beads, weaving yarn, and attaching feathers. He asked Hernandez if she was sure it would capture his nightmares. She told him to believe, the way he believed in her, to stay positive, and he would have good dreams. By the end of the module, he gave staff a thank you card and said he couldn’t wait for the next session. Hernandez says children are in awe of the consistency of these relationships. Kids have thrown markers at her on bad days and were surprised that she returned. “I’m still here,” she told them. “I’m not going to give up.”

The GREAT Youth and Families Program provides a safe space for children and youth. Along with counseling and art therapy, they also offer homework help and afterschool tutoring to help children improve in school and build skills for future success.

Healing pain with furry friends

Therapy Dogs United offers comfort and an opportunity to build nurturing connections with pets to children and families experiencing homelessness throughout Northwestern Pennsylvania and Western New York.

“Therapy Dogs United offers multiple programs and provides visits to local homeless shelters, group homes, and rehabilitation centers. Our ‘Courthouse Comfort Canine’ program invites certified therapy dogs to the Erie County Courthouse every Monday and Wednesday to benefit children facing dependency hearings in Family Court. Studies prove a certified therapy dog can provide comfort and support during a legal hearing by helping the child to relax and better focus. Therapy dogs provide a calming presence which helps alleviate trauma and stress. We bring our ARF (At Risk Families) Program to homeless shelters and group homes to help children deal with tough emotional times. This research-based program stresses the importance of humane treatment and compassion for animals and giving back by sharing our pets with others in need.

—Kelly Van Zandt

Emergency Room Mental Health Assessment and

Associate Director for Therapy Dogs United

Self-Care for Caregivers

Caregivers have a responsibility to prioritize their own emotional wellness. Nowhere is the old airline metaphor of putting on your own oxygen mask first more applicable than when dealing with a fragile population. “Our program encourages staff to do self-care,” says Schwartz of Housing Families. “I encourage everyone as a counselor to do their own therapy and figure out a self-care routine. The only way we can do our best work is when we are our best selves.”

Caregivers are adamant that supervision, discussion, and feedback happen regularly. “Helping people doesn’t mean fixing them or having results right away,” says Schwartz. “When counseling someone, I used to beat myself up over a stupid thing I said, and now I just say, ‘did I deem care and gentleness? Was I present?’ I often talk to my interns about what they can and can’t control. Give the person control of their lives rather than telling them what to do. Offer different ways to reduce stress because there isn’t one way that everyone is comfortable with. Offer support and childcare so parents can take care of themselves and take advantage of opportunities for stress reduction.”

Fun opportunities for expression are critical for stress reduction and promoting healthy child development according to the Homeless Children’s Playtime Project (HCPP). Healing play can happen anywhere, including a Quality Inn motel overflow shelter, shown here.

Facing the Future

In an uncertain political climate, clients are afraid. Fear is especially palpable for immigrants questioning their safety and futures. They don’t know what will happen to impact their ability to seek services. This worry adds another layer of trauma to assess and heal.

Yet, the future is bright. People Incorporated is one of six pilot sites in Minnesota for a new initiative called the Certified Community Behavioral Health Clinic (CCBHC)—a program of SAMHSA—offering behavioral, chemical, and physical health care. “These are opportunities to bring individuals receiving services in our system or with similar providers into an environment where we can look at the whole person and all their needs,” says Wiedemann-West. Providers will assess living situations, support services, transportation, and other factors impacting mental wellness. “I’m excited about the data that will come out of this two-year pilot project and what we’ll learn about best practices for working with this population,” she says.

Conclusion

Despite uncertainties, there is hope. This vulnerable population is resilient, as are the programs dedicated to eradicating their pain. “I think what’s most important is that we come with a sense of hope,” says Smith. “If you do not bring hope to the table with the families, it doesn’t matter what fancy intervention you use. You’re not going to get anywhere.”

Kids from the Housing Families Program share their thoughts and experiences:

“In group I learned to talk about feelings.”

“I learned that you aren’t the only one with problems.”

“I like myself more because I don’t feel alone.”

“In counseling I learned that I’m special.”

“I fight and argue less since I’ve been in group.”

Completely KIDS recognizes that children experiencing homelessness need social-emotional support. Their shelter programming provides children security and comfort, along with service learning opportunities. Here, a child in the Completely KIDS homeless shelter program points out dangers to pets during a field trip to the Nebraska Humane Society.

Resources

People Incorporated Mental Health Services ■ Boston Health Care for the Homeless Program ■ Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration ■ The Homeless Children’s Playtime Project ■ Community for Creative Nonviolence ■ Completely KIDS ■ Housing Families ■ Free Arts ■ Therapy Dogs United ■ Certified Community Behavioral Health Clinic ■

Spotlight on …

Denise Cerreta: A Warrior for Food Justice Is Now a James Beard Medalist

One World Everybody Eats (OWEE) is a national organization dedicated to helping launch community cafes—“pay-what-you-can” establishments where patrons without money can exchange an hour of setting tables, chopping vegetables, or other needed tasks, in exchange for their meals. Unlike soup kitchens, which sometimes rely on food donations of uncertain nutritional merit and taste, community cafes offer fare of the highest quality and draw patrons from all walks of life. (Those who can afford to do so are encouraged to pay the fair market price for their meal, and many chip in extra.)

OWEE had its genesis in 2003, when Denise Cerreta noticed some of the patrons at her small café were struggling to make ends meet and decided to begin letting them pay what they could for their food. Since then, more than 60 cafes have implemented the OWEE model, and collectively, OWEE cafes have served more than 2 million meals (almost a third of which were provided to people of less means).

UNCENSORED wrote about Cerreta and her admirable mission back in 2015, and we feel proud to have been prescient: On May 1, 2017 Cerreta accepted the James Beard Humanitarian of the Year Award, a prestigious designation recognizing visionary individuals and organizations working in the food industry, on behalf of OWEE.

“I am beyond humbled and honored,” she said upon receiving the award. “My hope is that this recognition will fertilize the seed in the hearts of others who also want to eliminate hunger.”

The National Perspective—

The Health Risks and Outcomes of Homeless High School Students

When speaking about homeless high school students, we primarily discuss their educational outcomes and graduation rates. This is largely due to the body of knowledge and data available on the subject, thanks to the information mandated by the McKinney-Vento Act. When it comes to the mental and physical well-being of homeless students, however, it is much more difficult to access data on the topic—when any is available at all.

With the ever-growing homeless student population, it is increasingly important that we pay attention to the mental and physical health of this vulnerable community. It is for this reason that the Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness released More Than a Place to Sleep: Understanding the Health and Well-Being of Homeless High School Students. The report explores the recent Youth Risk Behavioral Survey (YRBS) conducted by the Centers for Disease Control. This is the first time that the YRBS data has allowed localities to opt in and include questions that distinguish homeless students from their housed peers. This data allowed ICPH to examine the mental and physical health outcomes of homeless high school students. The findings are stark.

In New York City, one out of every eight public school students has been homeless at some point in the past five years, and of those students, 26% are in high school. It is no surprise then, that homeless high school students are facing a plethora of challenges. Among those is the task of balancing their mental, emotional, and physical health needs amidst all they are experiencing.

At only 12% of the YRBS sample, homeless high school students represent a third (or more) of all students facing a large range of health risks as well as making up a large segment of students facing the most extreme health risks.

Mental health struggles are a widely-recognized outcome for people who have experienced trauma. Homeless students are experiencing trauma every day and are often unable to access the supports that they need to stay healthy, heal from trauma, and do well in school. Over 40% of homeless students struggle with depression—a significantly higher rate than their housed peers. Even more striking is that homeless teens are more likely to consider suicide and are three times more likely to attempt suicide. Experiencing depression or suicidal tendencies as a teen can have long-lasting negative impacts on academic achievement, as well as health and well-being into adulthood.

In addition to mental health outcomes, homeless teens experience three times the rate of sexual and physical violence in their dating relationships when compared to teens who are not homeless. The research shows that homeless teens were more likely to be exposed to environments that promote high-risk sexual, alcohol, and drug use behaviors. Sexual and physical relationship violence as a teen increases the risks of depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). It also increases the likelihood of experiencing ongoing intimate partner violence as an adult, or becoming the victim of sex trafficking. Meanwhile, high-risk sexual behaviors such as unprotected sex and sex while under the influence of alcohol and drugs have been shown to increase chances of teen pregnancy, as well as contracting HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs).

Without proper policy and program interventions, the future of these homeless teens will be compromised. Recognizing the specific challenges and impact of homelessness on these students’ lives is needed to increase their access to supports in school. It is ICPH’s intention that states and communities will use the key findings and data in More Than a Place to Sleep to discover what programs are doing well and to improve those that may be underperforming. For more key findings, read the full report.

About UNCENSORED

Summer 2017, Vol. 8.1

Focus on Health

FEATURES

Outside the Box and Inside the Shelter: Preventing Injuries to Children Who are Homeless

Sheltered from the Storm: A Shelter-Based Program for Treating Opioid Addiction

Play, Art, Caring: Creating Emotionally Healthy Homeless Families

EDITORIALS AND COLUMNS

The National Perspective—The Health Risks and Outcomes of Homeless High School Students

Spotlight on … Denise Cerreta: A Warrior for Food Justice Is Now a James Beard Medalist

36 Cooper Square, New York, NY 10003

T 212.358.8086 F 212.358.8090

Publisher Ralph da Costa Nunez, PhD

Editor Joanne King

Assistant Editor Katie Linek Puello

Art Director Alice Fisk MacKenzie

Editorial Staff

Contributors Mary Curtis, Lee Erica Elder, Susan Fliesher, Mari Rich

UNCENSORED would like to thank Jesse Costa, WBUR, Boston Health Care for the Homeless Program, One World Everybody Eats, James Beard Foundation, Housing Families, Homeless Children’s Playtime Project, People Incorporated Mental Health Services, and Completely KIDS for providing photographs for use in this publication..

Letters to the Editor: We welcome letters, articles, press releases, ideas, and submissions. Please send them to info@ICPHusa.org. Visit our website to download or order publications and to sign up for our mailing list: www.ICPHusa.org.

UNCENSORED is published by the Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness (ICPH). ICPH is an independent, New York City-based public policy organization that works on the issues of poverty and family homelessness. Please visit our website for more information: www.ICPHusa.org. Copyright ©2017. All rights reserved. No portion or portions of this publication may be reprinted without the express permission of the Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness or its affiliates.

![]() ICPH_homeless

ICPH_homeless

![]() InstituteforChildrenandPoverty

InstituteforChildrenandPoverty

![]() icph_usa

icph_usa

![]() ICPHusa

ICPHusa