Publisher’s Note

Dear Reader,

Summer is the season that conjures up images of fun in the sun, vacations, and a break from school. But for homeless families—parents, young children, and college-age youth—this season can offer even more obstacles to overcome when school doors are closed and so are easy access to free meals, child care, activities, and college housing. In our feature, “Summertime,” we take an in-depth look at this issue and some of the programs that are meeting these unmet needs.

In “A Safe Place for Pets and People,” we explore how a beloved pet often presents an additional obstacle to entering shelter and receiving services, and the many organizations that work hard to break down that wall. “Pull Up a Chair and Pay What You Can” focuses on a growing business model that turns the concept of a restaurant on its head, encouraging customers to pay what they can afford—be it time or money.

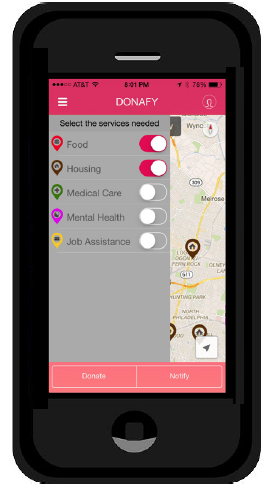

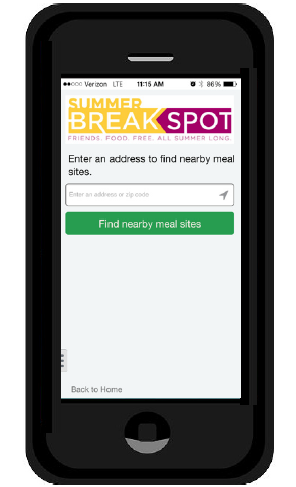

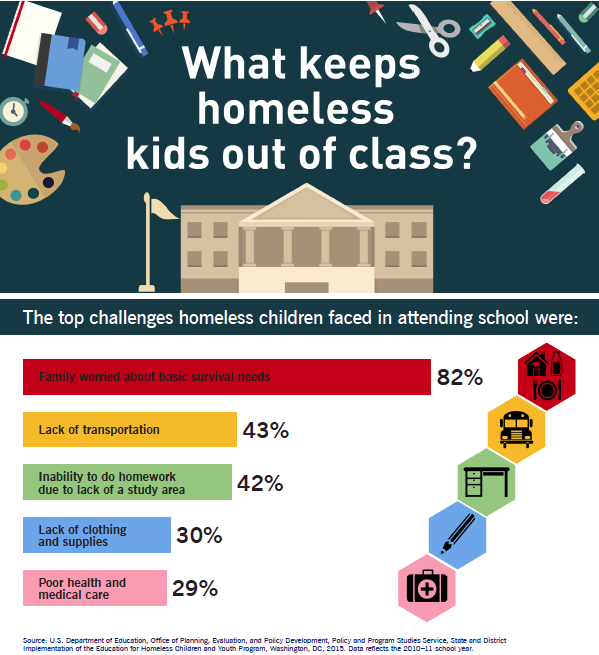

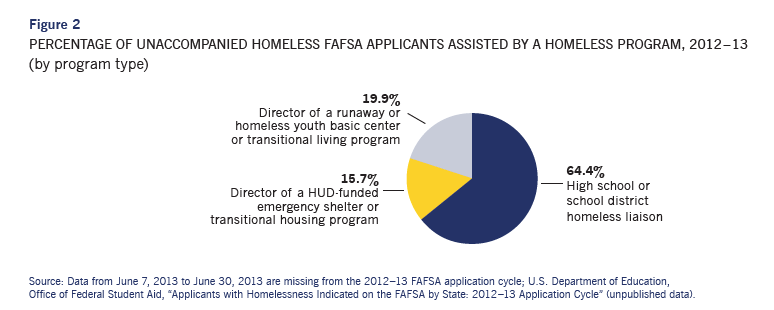

Our “on the Homefront” section offers up quick reads on innovative mobile phone apps that are making social services more accessible, a dispatch from a conference on poverty at Columbia University, an analysis that finds faults in the financial aid system’s assistance to homeless college students, and our latest “Databank” on why homeless students miss school.

We welcome your comments and ideas for future issues at info@ICPHusa.org.

Sincerely,

Ralph da Costa Nunez, PhD, Publisher

President and CEO, Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

A Safe Place for Pets and People:

Keeping the Whole Family Together

by Katie Linek

Housing. Education. Employment. These are the services that take top priority when helping homeless families achieve self-sufficiency. More and more however, service providers are noticing the existence of a large—but adorable—barrier to receiving these vital services: pets.

Nearly 70 percent of American households have pets. For many families, their animal companions are far more than just a pet—they are like a child, a sibling, or a best friend, providing unconditional love and support. Unfortunately, a majority of homeless shelters do not have the resources to house pets, leaving families with a difficult decision—give up an important member of the family or continue down the path of homelessness. In the case of people facing homelessness because of domestic violence, it can mean the choice between saving a loved one—the pet—or saving themselves. Too often, the result is families living in unsafe and unstable conditions—in their car, on the street, bouncing from couch to couch, or with an abuser—rather than sacrifice their beloved pet.

URIPALS, New York City’s first initiative to allow domestic violence surviors to enter shelters with their pets, helped Spike and Kirby’s family stay together in a safe place.

Shanna Dyott considers her mixed lab, Baby Girl, to be part of the family. Baby Girl has been with Shanna through the birth of her two sons, and is like a sister to them. When Shanna was let go from her job, the Dyotts were unable to make ends meet and were forced to leave their Arizona home, staying in a car for two weeks. “We had Baby Girl, and there was no one who would take her,” says Dyott.

That is why organizations across the country are stepping up to help keep homeless families together—including their pets. “We recognized that for the vast majority of families experiencing homelessness, if they want to receive services, they are not going to be able to keep their pets,” explains Claas Ehlers, director of affiliate services for Family Promise, a Summit, New Jersey-based nonprofit operating nationally that helps homeless and low-income families through a variety of programs. “We recognized that was an area we could have a specific impact on.”

Family Promise’s Arizona affiliate was able to provide the Dyotts a place to stay with Baby Girl. “For them to be able to help us out in this way … it kept our family together,” says Dyott.

More than 70 percent of pet owners who enter shelter report that the abuser has threatened, injured, or killed family pets. Up to 65 percent of domestic violence survivors stay in abusive situations or delay leaving out of fear of what would happen if they left their pets.

Family Promise provides shelter for families through a national network of interdenominational congregations, and has day centers where families can take showers, receive case management, and look for housing and jobs. In 2012, Family Promise partnered with pet supply retailer PetSmart to create PetSmart Promise, a program that provides options for homeless families to keep their pets while on the road to stable housing. The partnership expands existing Family Promise day centers throughout the country to include facilities for the pets of families who are temporarily homeless.

The PetSmart Promise program offers different options based on the needs of the family and the limitations of the Family Promise affiliate they are working with. The program offers on-site pet sanctuaries, free off-site boarding at PetsHotels, or a pet-fostering program for affiliates without access to a sanctuary or PetsHotel. By the end of 2015, PetSmart will have created 12 pet sanctuaries at affiliated sites across the country—ensuring that not only can families keep their pets; they will be able to interact with them every day.

“PetSmart wanted to make sure that with every one of our 182 affiliates, no family would go into shelter and have to lose their pet,” says Ehlers.

In New York City, the Mayor’s Alliance for NYC’s Animals, an animal welfare organization founded to reduce the rate at which New York City animals were being euthanized, began their Helping Pets and People in Crisis program in 2007. The program helps pet owners in difficult circumstances such as homelessness, domestic violence, illness, natural disasters, and other emergencies. They do this by offering creative solutions aimed at keeping pets with their families or reuniting them quickly once their situation is stabilized.

Jenny Coffey, a social worker who spearheaded the program confirms, “In traditional services, there is a major gap for pet owners facing crisis—we address those challenges head on.”

For homeless families, Helping Pets and People in Crisis will assist with emergency planning, such as helping to identify a friend, family member, or neighbor who could house the animal. They will also explore whether the pet is an Emotional Service Animal, a dog belonging to a person suffering from emotional or psychological disabilities, providing the pet owner with rights to have their pet nearby.

Supporting Healthy and Happy Pets

Those who do not enter shelter often still need help supporting their pet. Pets require food, toys, and often times, veterinary visits to stay happy and healthy. Individuals and families will care for pets on what limited resources they have.

Coffey explains that Helping Pets and People in Crisis provides resources for these families as well. “We can assess the animal and put in place low-cost or free veterinary care for spaying/neutering and vaccinations, as well as provide basic supplies such as a crate or pet food.”

In 2014, the Urban Resource Institute and Purina expanded the URIPALS program with the opening of the Purina Play Haven — New York City’s first dog park in a domestic violence shelter—so that dogs like Pepper can play and exercise while living with their families in shelter.

Nevada-based nonprofit organization Pets of the Homeless also provides pet food and emergency veterinary care to the homeless in communities across the United States and Canada. They have given care to over 12,000 pets, providing vaccinations, treating illnesses and injuries, as well as spaying and neutering. In addition, they have provided 355 tons of pet food and supplies to homeless and low-income pet owners.

“When faced with homelessness, what will become of a pet that you love?” asks Pets of the Homeless Founder, Genevieve Frederick. “The choices are harsh and many will not abandon or give them up. Our task, nationwide, is to relieve the anguish and anxiety of the homeless who cannot provide for their pets.”

“To have your pet sick and your hands tied, unable to get them care … that is a horrible place to be,” says Esperanza Zuñiga, program manager for Sacramento, CA-based RedRover, a national nonprofit that provides small grants to low-income families who cannot afford veterinary care for their pet, along with other life-changing grants. “We try to fill the small gap preventing them from getting the treatment to happen.”

RedRover provides financial assistance to individuals and organizations in an effort to break down the barrier pets present to families seeking help. “Our mission is to preserve and strengthen the human-animal bond and to bring animals from crisis to care, so when we learned about this barrier, we began creating programs to help pet owners during difficult times,” says Zuñiga.

For families and individuals resistant to entering shelter or receiving services for themselves, receiving help to save the life of a pet may increase willingness to receive other types of assistance. For example, once the pet is healthy and trust has developed between an individual and an organization, steps can then be taken to get them connected to the services they need. Coffey explains, “The pet is often an access point to engage with an individual—by helping the pet, a person may be more willing and able to accept help that will lead them both to safety and stability.”

Helping Families Heal, Together

Homelessness can be extremely traumatic. Along with their home, people experiencing it often lose their sense of safety and stability while facing the stigma and marginalization associated with homelessness. For survivors of domestic violence, this loss and trauma is multiplied.

“A lot of people do not realize that when you are a survivor of domestic violence and you make the really tough decision to leave, you leave everything behind,” says Jennifer White-Reid, vice president of domestic violence services for the Urban Resource Institute (URI), New York City’s second largest provider of domestic violence services. “They leave their family and their friends, their communities, their personal belongings, their computers, their books … and for those who feel like they have to leave their pets behind, it is so traumatic.” URI operates four domestic violence shelters with a total of 438 beds in Brooklyn and Manhattan, serving about 1,400 adults and children each year.

The Alle-Kiski Area HOPE Center in Tarentum, PA built on-site housing for the pets of domestic violence survivors through a RedRover Safe Housing grant and the help of Sheltering Animals and Families Together.

“In our work, we seek to save lives by offering a wide array of services including safe, confidential housing, case management, counseling, job training, children’s services, and mental health counseling,” says White-Reid. “We also provide community education and promote innovative best practices that would reduce barriers to safety.”

URI is the first organization in New York City—and one of few nationwide—to welcome pets into domestic violence shelters. “We want the family to heal together. To leave a situation where you are in crisis and to leave your pet that, for many survivors are part of the family, it is only adding additional trauma. So we offer an opportunity for them to be comforted by all of their family members while in shelter,” says White-Reid.

Essentially losing a member of the family intensifies the distress felt by survivors. Along with grieving the loss of the life they had, those who are forced to surrender a pet are also grieving the loss of a loved one.

URI is not the only organization to recognize the importance of limiting additional trauma to families. “We serve families no matter what their composition. We do not separate families. Why would we exclude the pets?” asks Ehlers of Family Promise. Homeless shelters generally serve very specific populations; while there are many places for homeless men or for homeless women with children, many shelters will not accept families with single fathers or two-parent families because adult men are often not allowed to stay in family shelters. Some shelters will not even accept teenage boys. Even more will not accept pets.

Compounding the grief of not having a beloved pet during a time of crisis is concern about the safety and well-being of the pet that was left behind. More than 70 percent of pet owners who enter shelter report that the abuser has threatened, injured, or killed family pets. Up to 65 percent of domestic violence survivors stay in abusive situations or delay leaving out of fear of what would happen if they left their pets.

The link between domestic violence and animal abuse serves as one of the primary areas of focus in the field of veterinary social work, an area of social work that concentrates on the human needs that arise in the relationship between humans and animals. “We promote awareness of the link between domestic violence and animal violence,” says Melissa Holcombe, a veterinary social worker and school social worker/homeless liaison for Catoosa County, Georgia.

Due to growing evidence of the frequent co-occurrence of animal abuse and domestic violence, 29 states, Washington, DC, and Puerto Rico now include animals on orders of protection, a legal order issued by a state court that requires one person to stop harming another person—or in this case, a person and their pet.

“Many of these families consider their pets to be like their children. The bond is that strong. Because of this, they have found that many women will simply not leave because they do not know what their pet will face without them,” explains Zuñiga from RedRover. “The pet will be a pawn in these situations. The abuser will say, ‘If you leave I am going to kill the pet’ or ‘Watch me do this to the pet and you are going to be next.’”

“Animals are often used by perpetrators to manipulate and prevent their partners from leaving,” adds Holcombe.

That is actually how the Helping Pets and People in Crisis program in New York City began. “Faced with domestic violence, a family refused to leave the situation because their dog, Maggie, would have been harmed,” says Coffey. “The Alliance accepted Maggie and found a foster home which lasted nearly nine months. The family secured a pet-friendly apartment and was able to reclaim their family dog. We believed that these situations happened a lot and felt that pet owners needed more support—especially if they were faced with circumstances beyond their control.”

Zuñiga tells the story of a woman in Kansas City, Missouri whose husband was attacking her with a hammer when the woman’s Great Dane lay down over her body to protect her and sustained the majority of the blows. The shelter she went to had a “no pet” policy, but she refused to leave him, so the shelter made a few phone calls and changed the policy that night. “It was so obvious why he had done what he had done and why she was not willing to leave him behind.” The pair will be included in an upcoming documentary titled The Deadly Link, about the connection between animal abuse and domestic violence.

Even more upsetting, many survivors will go back to an abusive relationship because of the pet. “We heard from a lot of survivors before we started this program,” says White-Reid about URI’s program, “about the grieving they experienced while they were in shelter and why some of them may have returned back to the relationship and put themselves in danger to check on their pet.”

Despite this, only an estimated five percent of domestic violence shelters have the ability to house pets on-site.

A Safe Place for Survivors

After a client of former Michigan prosecuting attorney Allie Phillips returned to her abusive husband in order keep her two dogs and goat safe, Phillips did some research and could not find a domestic violence shelter that would house pets. That is when she knew something needed to be done. She began developing guidelines for shelters to start programs for pets. In 2008, Phillips launched Sheltering Animals & Families Together, the first and only global initiative that guides family violence shelters in implementing programs to welcome families with pets.

In 2012, working with the Mayor’s Alliance for NYC’s Animals and Sheltering Animals & Families Together, URI launched PALS—People and Animals Living Safely. URI also teamed up with Purina, united by the belief that “people and pets are better together.”

Muriel Raggi, a domestic violence survivor who was previously in shelter, says she is thankful to URI and the Alliance for recognizing how important pets are in people’s lives. “I remember lying in bed at night, with so many fears and worries swirling in my head, wishing I could have my dog Jasmine next to me to provide raw affection, comfort, and support,” says Raggi. “URI-PALS will ensure that other survivors with pets will not face the heartbreaking choices I did.”

“Pets can provide a tremendous healing power. They can provide so much comfort to us. There is not only relief in knowing that you have not left your ‘child’ behind, but as a survivor you also get to benefit from your relationship with your pet.”

“Clients stay about six months to a year, which is a significant time to be away from a part of your family,” says White-Reid. “When we were exploring our options, boarding was not an option. Being away from them for that long, how are you continuing your relationship with the animal? How are they offering you comfort and support?”

RedRover also recognized the importance of providing a safe place for pets when trying to help survivors. That is why they offer Safe Escape Grants to pay for temporary boarding and/or veterinary care, enabling domestic violence survivors to remove their pets from an abusive situation and bring them to safety.

Lynn, her two-year-old daughter, and their one-year-old dog named Coco, constantly witnessed disturbing behavior from Lynn’s abuser. Lynn gained the courage to leave their abuser and fled to a nearby domestic violence shelter in Arkansas. Although the shelter was unable to house pets on site, Lynn’s case manager knew about RedRover’s emergency grant program and helped her get a Safe Escape grant that paid for 30 nights of emergency boarding for Coco and enabled the entire family to start a new life.

“My dog is everything to me, she is all I have left in my life. She is my baby,” says another Safe Escape Grant recipient from Illinois. “[RedRover is] a wonderful organization to help people in need, at a rough time in their life.”

According to Zuñiga, RedRover has provided over 6,000 nights of boarding for these pets. They soon realized however, that providing boarding was just a temporary solution. “We realized this was bringing animals from crisis to care, but it is a band-aid. We wanted to think more long-term. In 2012,” she says proudly, “we launched our Safe Housing Grant program, where we provide grants to help shelters purchase building supplies and materials in order to set up on-site facilities.”

Partnering with Sheltering Animals & Families Together, they have provided grants to 23 domestic violence shelters since 2012. In 2013, they launched SafePlaceForPets.org, a searchable directory of domestic violence shelters for families with pets.

A Sense of Normalcy

Experiencing homelessness, witnessing the abuse of a pet or loved one, or experiencing abuse themselves can have numerous negative outcomes for children and families. Research has shown that up to 76 percent of animal cruelty in the home occurs in front of children, who often intervene or allow themselves to be victimized to save their pets from being harmed or killed. Animal cruelty coincides with outbursts against human family members more than 50 percent of the time.

According to one study, “children who are exposed to domestic violence are nearly three times more likely to treat animals with cruelty than children who are not exposed to such violence.” The National Coalition Against Domestic Violence claims that 32 percent of mothers in a domestic violence shelter reported that their children had hurt or killed animals.

“It is extremely traumatic for a child to witness animal abuse. That child then has an increased likelihood of committing those acts,” explains Zuñiga. “Children who observed acts of violence in the home prior to the family leaving were already copying the abuser. In terms of coping strategies, what does this child now do when they are angry? When they are sad? And unfortunately that pet can be the first thing they use as an outlet. So many of these abusive situations are cyclical.” Fortunately, when the whole family, including the pet, is brought to safety, the child can see the value placed on the life of their pet and begin to learn the proper way to relate to and treat animals.

The chronic stress faced by children who have experienced homelessness and/or domestic violence may also lead to several problems. Prolonged stress in children has been shown to impair brain development, cause behavioral problems, negatively affect coping abilities, cause depression and anxiety, and strain social relationships. Specialized programming targeted toward this vulnerable population can mitigate the effects of this stress though, emphasizing the importance of getting families into shelter as soon as possible. Allowing pets to join their families eliminates one more obstacle to getting them there.

“We want families to receive services,” says Ehlers of Family Promise. “We want to be able to work with families, to empower them out of homelessness and if they are not receiving services they are far less likely to get on a pathway towards self-sufficiency.”

The shortage of homeless shelters that accept pets has an added layer of complexity for unaccompanied youth, points out Holcombe, who works with unaccompanied youth as a school social worker and homeless liaison. “We do things in the community to try and support these kids to make sure that they take advantage of the educational system, graduate, and become productive members of society,” she explains. “According to my research, there are a lot of kids who have pets, but will not go to get help or go to school because they do not have anywhere to keep their pets. The very thing that they need—education—they will not get.”

Concern for a pet who was left behind can also be a distraction for many children and youth when they should be learning. “The kids focus on and worry about their pets, almost to the point of obsession,” says Holcombe.

In addition, the consistency and stability provided by the presence of family pets support children’s social and emotional development, as well as providing a sense of normalcy in what is likely a chaotic life. To aid in providing this sense of normalcy, PetSmart donated and installed over 80 aquariums at Family Promise affiliates across the country. The fish are used to teach children about the care and responsibility needed when owning a pet. “It calms and centers the kids,” explains Ehlers. “It is little things like that that provide a normative element that children experiencing homelessness can often lack.”

Pets provide both children and adults with comfort and support during a very difficult and scary time in their lives. “Pets can provide a tremendous healing power,” says Zuñiga. “They can provide so much comfort to us. There is not only relief in knowing that you have not left your ‘child’ behind, but as a survivor you also get to benefit from your relationship with your pet.”

“When you talk about that bond, that unconditional love that the kids and adults get from their pets … not having that takes away a large potential for coping,” adds Holcombe.

In fact, studies show that having a pet can reduce blood pressure, heart disease, and stress, while improving one’s mood. Pets give a sense of belonging and meaning as well as a greater sense of control.

Bringing Communities Together

The building of facilities for pets and the implementation of these programs have had an unexpected, but welcome side effect: bringing communities together.

“A lot of times when it comes to the construction of these shelters, the Eagle Scouts will come do it or a construction company offers to donate their time,” says Zuñiga. “It is really neat to see how proud these communities are of their programs.”

Ehlers adds, “It is all about creating that community; creating that interaction between people experiencing homelessness and the people who want to help. Together, they can create these community transformations.”

“There are a lot of kids who have pets, but will not go to get help or go to school because they do not have anywhere to keep their pets. The very thing that they need—education—they will not get.”

“What is equally awesome is that when these communities, who previously did not have anything to do with pets, reach out to their donor pool with this new effort to help pets, their community rises up with donations and food and treats and toys so that they can sustain their programs,” Zuñiga continues. “It is really beautiful.“

Ehlers confirms that adding pets to the mix has expanded their donor base. “Our affiliates that have built the PetSmart Promise sanctuaries have had people send them checks that they have never heard of before with the subject line reading ‘Cat Lover.’”

More importantly, pet programs are changing communities’ perceptions about family homelessness. “There are people who do not understand family homelessness, but if you ask them what a homeless family is supposed to do with the dog that they have had since their child was a baby, they get it,” explains Ehlers. “It breaks down that ‘otherness.’”

The public perception of homelessness is often the idea of a man on the street, with mental health or substance abuse issues. Pet initiatives draw in new volunteers and remind them that homeless families are just like any other family.

“What you prevailingly see is people not understanding that first of all, people experiencing homelessness often have jobs; people experiencing homelessness often have an education; people experiencing homelessness are as committed to their families as families who are housed,” says Ehlers.

Overcoming Fear

Implementing these programs is far from easy though; initiatives to care for the pets of homeless families have a wide variety of factors to consider. Will pets be housed in a resident’s room, in an indoor or outdoor kennel on-site, boarded off-site, or fostered?

There are also concerns about allergies, odors, noise, pet health and medications, cleaning up waste, pet hygiene, the size and type of animals allowed, and the comfort of the pets, including physical comfort (will dogs have enough room to run and play?) and psychological comfort.

For many animals, leaving home—even an abusive one—can be extremely stressful, especially if they need to be housed in smaller quarters. This stress and/or a history of being abused or witnessing the abuse of their owner can cause aggression. Many times, shelters will actually bring in a behaviorist to address these issues. Counseling may also be provided to residents who have witnessed the abuse of their pet, which can cause significant trauma and psychological damage to both adults and children.

White-Reid tells the story of a client who came in with her seven-year-old daughter and their cat Chowder. “Her abuser did a number of things to threaten her cat including placing him in the closet, leaving him out in the cold, and tying him up, placing him in the microwave, and threatening to turn it on if she did not do what he ordered her to do. In shelter, if someone knocked on the door, Chowder would run and hide. We partnered with the ASPCA (American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals) and they brought in a behaviorist who worked with Chowder, the mom, and the daughter on several behavioral techniques to help Chowder overcome his fear. And it really worked. During the time that they were with us, we saw a radical change in Chowder’s behavior. He became more playful and he did not run and hide any longer.”

To guide organizations through the complicated process of opening their doors to pets, Allie Phillips from Sheltering Animals & Families Together created a detailed start-up manual that breaks down the factors involved. In it, Phillips recommends three essential policies:

■ Partnering with an animal protection organization for guidance on animal housing issues, local regulations and ordinances impacting the housing of animals, and to assist when difficult complications arise.

■ Working with a veterinarian to provide medical care, such as an initial examination to determine if the pet has been abused or neglected and needs treatment; general care such as updating vaccinations, flea and parasite treatment, or spaying/neutering; emergency care in the case of illness or injury; and to offer an expert opinion in court if the need should arise to verify animal cruelty.

■ Only allowing the family and designated shelter staff to interact with each pet for the safety of other residents and staff.

With the help of Phillips, URI created a model that was safe and beneficial for all involved. “We recognized the importance of partnering with animal welfare experts in order to make sure that the program was safe for everybody—the clients who had pets and those who did not, as well as the staff,” White-Reid explains. “We came up with a wonderful model that includes staff training, pet safety education, pet food and supplies, transportation—all sorts of things to make sure they are happy and healthy while they are in shelter with their family.”

“Then we work on discharge planning,” White-Reid continues, “to help families identify what needs their pet may have, and to be sure that when they transition to permanent housing there are pet-friendly options available.”

‘Why We Do What We Do’

Although the process is complicated, each organization agrees that the effort is worth it.

“I go on site visits and I see first hand the impact that we have had,” says Zuñiga. “I have had ladies run up to me in tears, crying, and hugging me saying, ‘If it was not for you, I would not be here,’ but here she is with her two cats. It reminds us that this is why we do what we do.”

“We can see real life progress in families,” says White-Reid. “We get to see the adults heal and blossom as they transition into permanent housing and we see the same for the pets.”

Resources

Family Promise, www.familypromise.org Summit, NJ ■ PetSmart Gives Back, www.petsmartgivesback.com Phoenix, AZ ■ Mayor’s Alliance for NYC’s Animals Helping Pets and People in Crisis, www.animalalliancenyc.org New York, NY ■ Pets of the Homeless, www.petsofthehomeless.org Carson City, NV ■ RedRover, www.redrover.org Sacramento, CA ■ Urban Resource Institute, www.urinyc.org New York, NY ■ Sheltering Animals & Families Together, Alexandria, VA ■ National Coalition Against Domestic Violence, www.ncadv.org Denver, CO ■ American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, www.aspca.org New York, NY.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

Summertime:

Not a Break for Homeless Families

by Lauren Blundin

Every June, kids across the United States are counting down to summer vacation. They cannot wait for the break—a time for family outings to beaches, parks, and museums, for riding bikes and going swimming.

Summer also brings a less welcome phenomenon—often called the “summer surge”—of increasing numbers of people, including families, needing shelter. There are many reasons for this increase, but at least one cause can be linked to the summer break itself; relatives and friends who have allowed homeless families to live with them during the school year are less patient with the situation once summer break has started and children are home all day.

For children experiencing homelessness, a break from school can mean a break from the one stable place in their lives. “School is a critical, normalizing part of life,” says Nan Roman, president and CEO of the National Alliance to End Homelessness. “School is a time for being with peers, pursuing interests, and being out of the stressful situation of being homeless.”

Located in Cincinnati, Ohio, the Yellow Bus Summer Camp offers young homeless children living in shelters free meals each day as well as swimming gear, and offers many exciting, first-time learning experiences.

Different Challenges and Barriers

Summer break often finds homeless students without a safe place to play and without opportunities for educational or cultural activities. Sadly, summertime for some kids also means having fewer positive interactions with caring adults.

Summer learning loss—the loss of academic knowledge and skills over the break—is a concern for all children. Homeless students in particular cannot afford to lose skills, as they are often already behind their peers academically.

With 1 child in 30 homeless every year, the public school system is the obvious choice for providing and funneling services and supports to homeless children and their families. Schools may provide free breakfasts and lunches (and less frequently, dinners), access to health care and dental care, food pantry programs, access to before- and after-school care, and enrichment activities. When the calendar flips to June, the need for food, quality educational activities, and other services does not just go away.

The Hunger Gap

“About 21 million students receive free and reduced price meals at school during the school year,” says Ross Fraser, director of national relations for Feeding America, which represents a nationwide network of member food banks. “Of those, about 10 million also get a free breakfast. So for a significant number of children there are one or two meals a day they receive free or at a reduced price.”

What happens during the summer break? There is a U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) summer food service program, but it reaches only about one in eight, or 20 percent, of the children who receive free or reduced price meals during the school year. Lack of transportation to the summer meal sites is a common barrier for children, especially those in rural areas, resulting in a huge gap between the number of children eligible for food programs and the number of students accessing those programs.

Breaking Down Barriers to Food

Feeding America’s member food banks work with national donors to move food to 60,000 different programs. Special summer programs try to reach the other seven in eight children who still need food assistance. “A lot of our food banks are finding innovative ways to feed kids during the summer,” says Fraser. “Some have retrofitted school buses to drive around and stop at different trailer parks to feed kids. Some are partnering with the public library. Innovation is the name of the game—trying to find new ways to get food to children.”

In childhood hunger, the stakes are high. Inadequate nourishment can hinder intellectual, emotional, and physical development and set a child up for failure in school later on. Add to this the phenomenon of summer learning loss. Clearly, the need for summertime academic intervention and enrichment for children experiencing homelessness is an urgent one.

Serving the Unseen

The Yellow Bus Summer Camp addresses this need head-on in Cincinnati, Ohio. For 18 years, the yellow bus has transported children ages 5 to 12 from shelters to summer fun and learning. The camp is run by the nonprofit Faces without Places and provides a free breakfast and lunch each day. The camp also provides each camper with a swimsuit, towel, and shoes. The camp is exclusively for students experiencing homelessness, and is free of charge.

“We are the only local nonprofit that exclusively serves the educational needs of students experiencing homelessness in the greater Cincinnati region [which includes parts of Kentucky],” says Mike Moroski, executive director. “That number on average is 6,000 students a year. Kentucky is ranked last in the nation regarding childhood homelessness. Cincinnati has the second worst childhood poverty rate in the country at 52 percent. That is not to paint a doom and gloom picture of the region. I just find that when I state those two numbers in the region, people seem shocked. It is literally an unseen population.”

Hands-on activities such as pizza making, provide learning opportunities and teach nutrition, the importance of healthy eating, and cooking skills. The activity is part of the GREAT Youth and Families summer camps hosted by Housing Families in the Boston area.

Faces without Places supports the educational needs of this unseen population year-round. A mentoring program pairs homeless and at-risk youth with university students, while a literacy program brings regular story times and books to homeless shelters for children of all ages. A third program, the Education Stability Collaborative, provides transportation and material supplies that students need to attend school. But the Yellow Bus Summer Camp is the flagship program.

For eight weeks, kids at the Yellow Bus Summer Camp play sports, go on field trips, and swim. They also learn. In fact, the camp’s true focus is developing children’s literacy and math skills.

“We hire real teachers for the summer,” says Moroski, “and we pay them competitively.” The camp’s investment in certified teachers has paid off. A 2014 analysis of the Yellow Bus Summer Camp found 95 percent of campers retained or increased their literacy and/or math skills. Campers also made significant gains in measures of well-being such as health, self-confidence, stability, belonging, and comfort.

Parent Kelly O’Brien found out about the Yellow Bus Summer Camp last summer when she and her three children were staying in a shelter in Kentucky. “Faces without Places helped me tremendously,” says O’Brien. “At the time I needed to focus on getting out there and getting interviews so that I could get a job and get out of the shelter. Summer programs are so expensive.”

O’Brien enrolled her school-age daughter in the summer program and was able to job hunt while her daughter had a safe place to go each day and learn. “She got to experience things she would not normally get to do,” says O’Brien. “Like go behind the scenes at the airport and see the police dogs. She also went on a boat ride up and down the Ohio River. The camp is creating these experiences for kids instead of letting them hang out in an apartment or a shelter all day. The program helps keep kids positive and not focusing on the stressful situation at home.”

Changing Lives

In Maryland, the Boys and Girls Club of Frederick County provides summer academic enrichment for students ages 6 through 14, some of whom are experiencing homelessness and living in transitional housing or shelters. Located in Frederick County—a rural, bedroom community with a large population of commuters to Washington, DC and Baltimore—the Club serves children from the city of Frederick and its surrounding suburbs. The program is not free, but the organization works hard to keep costs down and affordable, and offers some scholarships. The high-quality, affordable camp opportunity is so popular that online registration can fill within 30 minutes of opening to the public.

According to Executive Director Patrick Gunnin, the summer camp provides a critical stability and daily routine for children. The camp also provides extended hours before and after camp so that parents who are working can drop students off and pick them up after work. As with the Yellow Bus Summer Camp, this camp focuses on academics.

Schools may provide free breakfasts and lunches (and less frequently, dinners), access to health care and dental care, food pantry programs, access to before- and after-school care, and enrichment activities. When the calendar flips to June, the need for food, quality educational activities, and other services does not just go away.

“Programmatically, we are trying to reduce that summer learning loss,” says Gunnin. “Especially for students with special needs. We try to do this in a fun manner in which they will enjoy learning, but not in a structured setting.”

Parent Kafilat Akande has seen her son D’quami Brown, 10, thrive during his three years with the Boys and Girls Club of Frederick. When D’quami started with the program, he and his mother were homeless. He has attended the summer camp on scholarship each year since then, although they are no longer homeless. Akande says that the camp helped her son learn to interact with his peers. “He had been through a lot,” she says. “D’quami was one of the homeless children going to the club. He needed a place to relax and be a kid—somewhere he did not have to feel like he was taking on so much. I needed him to be in a place where he could be a child with other kids, and be happy. The camp gave him the opportunity to just relax and have fun.”

According to Akande, some of her son’s favorite activities at summer camp are basketball, science experiments, guest speakers, and field trips to museums. He has also developed an interest in history. When asked if the summer program has supported D’quami academically, Akande says, “Let us talk statistics. Last year he was a C student. After the summer program, D’quami has made the honor roll all three times.”

The day she walked into the Boys and Girls Club of Frederick County, Akande’s life changed. She herself was a homeless parent searching for a job and a quality program for her child. She found both. The same day she enrolled D’quami in camp, Akande was hired to work as the camp bus driver, where she immediately developed close relationships with each child, making a point to get to know each one individually. She later began providing enrichment activities in different club locations. Today, Akande is a program director for the Boys and Girls Club of Frederick County, and she is just as passionate about improving students’ self-esteem as she is about improving their academics. “The Boys and Girls Club of Frederick County changes lives,” she says.

Having a GREAT Time While Learning

Housing Families, a family-focused shelter in the Boston area, provides a year-round after-school program for children as well as a series of two-week summer camps to reach as many students and age groups as possible. The camps are designed to help reduce summer learning loss through fun, hands-on activities. The camps also give kids the chance to try things like horseback riding, which they otherwise would never have the chance to do.

The camp’s full name is the GREAT Youth and Families summer camps. The GREAT in the program’s name is an acronym that staff created to describe the qualities that the program nurtures in children: Growth, Resilience, Empowerment, Acceptance, and Trust. Of course, the kids just think they are having a great time while doing experiments and taking field trips.

“The program provides a lot of learning, but within activities, so the kids do not realize they are learning,” says Siobhan Malady, program manager for the shelter’s GREAT Youth and Families summer camps. “We do a lot of science activities here. Last summer, we made ‘poop’ by mixing food with vinegar and squeezing it through nylon. The children were able to explain the process of how food moves through the body. And a year later they are remembering this.”

In addition to combatting summer learning loss, Barbara Schwartz, director of the GREAT Youth and Families program, believes the camp provides parents a much-needed respite from supervising children. “Most of the parents I know are inordinately stressed because they feel like their kids are with them 24/7 in the summer, and they do not get a break.” Summer camp gives parents that break.

Homeless at College

Most programs and legislation for the education of homeless students target kindergarten through 12th grade, but students in college are vulnerable to homelessness as well, particularly in the summer. The trend of the “summer surge” of homelessness in shelters is echoed at colleges across the country each spring as students lose access to college-provided housing and/or deplete their financial aid for the year and struggle to afford housing on or near campus.

Four-year colleges generally provide housing to students, but at a significant cost, and not always year-round. “We certainly see students struggle with housing during breaks,” says Cyekeia Lee, director of higher education initiatives for the National Association for the Education of Homeless Children and Youth (NAEHCY). “Of course, in community college there is no housing at all, so those students struggle year-round. For students on campus, summer is the longest break. It can make the difference between a student coming back for sophomore year or not. Sometimes they have to go to a different state for housing with friends or family, and they might not return.”

“A lot of students have not been taught how to plan financially. They do not come from homes or places where you have conversations about how to budget—to know that if you have $2,000 in aid that is just for housing, you will still need money for food, toiletries, and those types of things.”

Many college students are reluctant to reach out for help, and try to avoid shelters. “I have had students call me from barns,” says Lee. “Some students are saying they live in 24-hour school libraries, and some are sleeping outside, but they may not say that to a lot of people.”

Marcy Stidium, director of the Campus Awareness, Resource and Empowerment (C.A.R.E.) Center for homeless and at-risk students at Kennesaw State University in Georgia, explains why students may run into trouble in the summer. “A lot of students have not been taught how to plan financially,” says Stidium. “They do not come from homes or places where you have conversations about how to budget—to know that if you have $2,000 in aid that is just for housing, you will still need money for food, toiletries, and those types of things.”

Students may fund tuition through scholarships or financial aid, but those funds are usually depleted by the summer time. Housing and food is expensive, and there may be limited availability to both during the summer. For example, a student who relied on her meal plan throughout the year may face hunger when she finds the plan does not extend over the summer. Students who rely on campus transportation systems to get to work can also find that reduced bus schedules make it challenging to get to work. While work-study is usually available, the number of hours available for students to work depends upon the department’s funding. Often, students will deplete their allotted work-study hours before the summer break, leaving them scrambling to find employment for the summer. These factors combine to create huge barriers to staying in school for homeless students. Some colleges have started to recognize and support the homeless populations on their campuses.

Unconquered Scholars

The Unconquered Scholars Program at Florida State University (FSU) is an intensive support program for students who have experienced foster care, homelessness, relative care, or ward of the state status. The program is a subset of the broader Center for Academic Retention and Enhancement, which supports FSU’s first-generation college students who have been economically disadvantaged.

“Out of the youth who age out of foster care, only about two percent ever achieve a bachelor’s degree, compared to about 28 percent of the general population,” says Lisa Jackson, program coordinator of Unconquered Scholars. “So they are extraordinarily at risk of not obtaining a degree.”

For eight weeks, kids at the Yellow Bus Summer Camp play sports, learn, go on field trips, and swim. Most importantly, the experience allows kids to be kids when summer is in full swing.

Jackson believes there is not a time when students are not vulnerable to becoming homeless, but concedes that the winter and especially summer breaks do require planning to avoid disaster. “Whenever we have a scheduled break when the dorm is closing, that is when I feel my students are at the greatest risk of homelessness. We do not have many dorm spaces available over the break, so we have to work very closely with the housing office.”

Asked why former foster and homeless students would have difficulty maintaining homes, especially during the summer break, Jackson cites what she believes are the three major reasons: “Lack of financial management, not having a ‘forever family,’ and having a strong sense of self-reliance,” which Jackson says is common among former foster children. “That can make the student not ask for help.”

In terms of financial management, Jackson is referring to the challenge most college students face in making their financial aid, loans, and any personal savings stretch far enough to cover expenses over the summer break. Most college students can fall back on their immediate and extended families if they need to, however, explains Jackson, “Many of our students do not have what we call a forever family. So when money is tight, they do not have anyone to go to.”

To avoid these situations, Jackson brings up financial issues early and often with students. “When I meet with them, we will talk about financial responsibility, and I will say let us make sure we budget. There are conversations we have to try and address these things. How each person responds to the conversation, though, varies.” She says she tries to “stay ahead” of the summer break by encouraging students to plan well ahead of time.

To further prepare students for the financial challenges that hit especially hard each summer, Unconquered Scholars will be rolling out a new financial therapy model in Fall 2015. “It is one thing to sit down with a student and say let us work on a budget to make sure you are saving,” says Jackson. “It is another to help them understand the emotional reasons of why they want to spend and why they might overspend … to really prepare them for it and to help them make more sound financial decisions.”

Caring College

Kennesaw State University recognized that students without strong home support systems were struggling to stay in school and maintain housing. The University created the Campus Awareness, Resource and Empowerment (C.A.R.E.) Center to support students who are homeless or are at-risk of being homeless. The Center provides students case management services and access to food, clothing, and emergency shelter. The Center is also the designated campus contact in a statewide network to support former foster youth.

“I was directed to the C.A.R.E. Center by my academic advisor,” says Amberlyn Hutton, a student at Kennesaw State University who recently became overwhelmed financially and lost her housing, despite working two jobs. “I was talking to her, letting her know that I had nowhere to live. I had been really stressed because I had picked up a second job to make ends meet, so I was not able to go to class. I said to my advisor, ‘Maybe I should withdraw?’ And my advisor said that instead of withdrawing, I should call the C.A.R.E. Center. Within three days they found me a place to stay on campus that will be free until the lease is up in July.”

“I get financial aid, and I have student loans as well. However, my aid was not enough to cover the entire semester for me to stay on campus. I tried to stay with my parents but that did not work, and I got put out. I went from place to place, then started to sleep in my car.” Will Hutton be able to resume taking courses again in the fall? “It depends,” she says. “Housing on campus at Kennesaw is so expensive. I do not know.”

Hutton’s situation is painful and traumatic, but not necessarily unique. Financial aid only goes so far. She is working as much as she can this summer. She works part-time as a pharmacy technician during the day, and works at Chick-fil-A in the evenings. As of July, her housing situation, and the future of her education, is in question. She says she will do her best to stay in school, but covering her expenses during the summer break is tough and has set her back. “I have another meeting on Monday at the C.A.R.E. office to talk with them to see what I should do next,” she says. (To learn more about Kennesaw State University’s efforts to help students experiencing homelessness, see “Building Bridges” in our Spring 2015 issue of UNCENSORED.)

Growing Problems with Shrinking Budgets

School districts and communities are aware of the many needs of students during the summer break from school. The challenge, however, is meeting those increasing needs with a stagnant or shrinking budget. The number of homeless students more than doubled between the 2004–05 and 2012–13 school years according to the nonprofit research center Child Trends. Funding for public schools, however, has actually decreased in at least 30 states since the national recession of 2007–09. As school districts struggle to meet the needs of increasing numbers of homeless students during the school year, budgets for existing summer programs may suffer.

Barbara Wand James is project director for the Texas Homeless Education Office (THEO), a research unit of the University of Texas at Austin. She works with the Texas Education Agency and its regional service centers to support the education of homeless children.

Snakes and lizards and turtles — oh my! In addition to year-round programming, Housing Families offers two-week summer camps designed to help reduce summer learning loss through engaging activities. Hands-on experiences, like learning about reptiles, enrich their science skills in a fun new way.

James describes the problem this way. “We are seeing increasing needs for services with stagnant dollars. Some of our projects have cut out summer programs this year as they felt they did not get enough dollars to support a viable summer program.”

“The region 12 education service center at one time had a very large summer program [geared toward homeless students],” says James, giving an example. “They brought in kids from all over the region for the summer. It was very impressive, the kids loved it, and they had great learning activities. Unfortunately, their grants kept dwindling, and they got to the point where they could not provide that programming any longer.”

“There was a lot of attention and collecting data on summer programs after the recession, finding a striking difference in funding [before and after the recession], and seeing a lot of districts cutting funding,” says Erik Peterson, vice president of policy for Afterschool Alliance, an advocacy group for summer and afterschool programs. “We have seen a little bit of that funding come back, but not to levels before 2008.”

“We are seeing increasing needs for services with stagnant dollars. Some of our projects have cut out summer programs this year as they felt they did not get enough dollars to support a viable summer program.”

“In terms of general trends, funding continues to be a challenge for programs and parents,” says Peterson. “The key piece is that the number one source of funding is parent fees, and that is even true for low-income parents.” In 2014, parents on average paid $281 per week for summer learning programs. For families experiencing homelessness, that cost is a monumental barrier.

Both the federal 21st Century Community Learning Centers (CCLC) program, which supports the creation of centers that provide academic enrichment opportunities for children who attend high-poverty and low-performing schools, and summer meals programs, provide funding for summer programs across the country. States administer more than $1.1 billion in federal funding through 21st CCLC and $461 million through summer meals programs. According to Peterson, funding for these programs remained steady this year. In terms of state funding, the picture is less clear. “Some states are putting more money back into education in general, and that is translating into summer learning,” says Peterson. “But some states are further behind.”

Moving in the Right Direction

In a move that will help stem the summer surge at the higher education level, NAEHCY is working with states to create higher education networks that will support homeless and unaccompanied youth and increase their access to higher education. Funding is an issue here too. “The state networks, except for two, do not have funding attached to them,” says NAEHCY Director of Higher Education Initiatives Cyekeia Lee. “The vast majority of state networks are volunteer, and their staff are working to connect students to resources that already exist. Those few that do have funding have very small amounts of funding. We are hoping that funders will see that there is a need for this population.”

The state of California recognizes the value of higher education support for students at risk of homelessness. This session lawmakers considered legislation that would require higher education institutions to create a point of contact for homeless students on campus. This point of contact is a person who could help students prepare for the inevitable challenges of summer ahead of time. A decision on the law has yet to be made, but the potential is encouraging.

A Future at Stake

The summer learning loss phenomenon is a concern for all children. The stakes for homeless and economically disadvantaged children, however, are much higher than those of their economically stable peers. A study of the long-reaching consequences of the summer learning gap traced high school achievement back to first grade to see how early elementary summer experiences influenced later achievement. The results were astounding. A child’s achievement gains over the first nine years of schooling were found to be the result mainly of learning during the regular school year. But the achievement gap between high and low socioeconomic statuses at the ninth grade was mainly due to differences in summer learning over the elementary years. These summer experiences substantially influenced whether a child was placed in a college prep track at the high school level, whether a child graduated high school, and whether he or she attended college.

Anyone Could Need Help

Hardworking parents like Kelly O’Brien rely on programs like the Yellow Bus Summer Camp from Faces without Places to help ameliorate the socioeconomic achievement gap for their children. She wishes people understood that these programs are valuable and worth the investment in children’s lives. “I wish people could understand it could be their neighbor and their neighbors’ kids going through homelessness,” she says. “You would want your neighbors’ kids to have a safe place to go, so you would want to support a summer program like this.”

Resources

National Alliance to End Homelessness, www.endhomelessness.org Washington, DC ■ Feeding America, www.feedingamerica.org Chicago, IL ■ U.S. Department of Agriculture, www.usda.gov Washington, DC ■ Faces without Places, www.faceswithoutplaces.org Cincinnati, OH ■ Boys and Girls Club of Frederick County, www.bgcfc.org Frederick, MD ■ Housing Families, housingfamilies.org Malden, MA ■ National Association for the Education of Homeless Children and Youth, www.naehcy.org Minneapolis, MN ■ Campus Awareness, Resource & Empowerment Center, Kennesaw, GA ■ Unconquered Scholars Program, Tallahassee, FL ■ Child Trends, www.childtrends.org Bethesda, MD ■ Texas Homeless Education Office, Austin, TX ν Afterschool Alliance, www.afterschoolalliance.org Washington, DC ■ National Summer Learning Association www.summerlearning.org Baltimore, MD.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

Pull Up a Chair and Pay What You Can:

Working to Ease Food Insecurity and Bridge Social Divides

by Mari Rich

Georgia Bowen has come a long way since 2006, when she left an abusive marriage and entered a homeless shelter with her three children. Inspired by the philanthropic organizations that helped her during that period, she is now earning a graduate degree in nonprofit management. She is also a regular patron of F.A.R.M. Café in Boone, North Carolina. “Like many people, I struggle sometimes,” she says. “Even when I have been working 90 hours a week at three different jobs, it has happened. It still happens now that I am a graduate student dependent on fluctuating levels of financial aid. But if I have only a few dollars in my pocket—or even if I have no money at all—I know that my children and I can get a healthy, wonderful meal there.” That is because F.A.R.M., Feed All Regardless of Means, is one of a growing network of community cafés set up with the help of One World Everybody Eats (OWEE), a national organization dedicated to spreading the word about a new type of restaurant.

Volunteers serve food at Fareground, a “pop up” pay-what-you-can restaurant in Beacon, New York.

Diners at a community café pay whatever they can. Although the establishments usually post a suggested price—typically $5 to $10 for a freshly prepared multi-course meal—patrons who can afford to do so are encouraged to donate a little extra. Those strapped for money can exchange an hour of labor, such as setting tables, chopping vegetables, or an assortment of other needed tasks, in exchange for their families’ food. (For those unable to work or pay, many cafés also serve a simple daily dish that can be enjoyed with nothing expected in return.)

A ‘Field of Dreams’ Moment

OWEE had its genesis when Denise Cerreta, a Salt Lake City-based acupuncturist, woke up one day only to find she had hit what she terms a “spiritual glass ceiling.” Her patients, she realized, were suffering more from loneliness than from physical ailments, and in 2002 she opened a small coffee-and-sandwich shop, meant to serve as a welcoming place where community members could gather. Despite her good intentions, the venture was not an immediate success; Cerreta soon found her car repossessed and her rent in arrears. Most people would have been tempted to abandon the project at that point and go back to their former jobs. Cerreta might have considered giving up as well, had it not been for what she calls her “Field of Dreams” moment—a reference to the iconic film of that name in which an Iowa corn farmer builds a baseball diamond on his property, certain that players and spectators will come. Her notion—which seemed equally fanciful—was to let customers pay whatever they could afford for their food.

While the idea may have seemed impractical, it was unusual enough that customers and members of the media began flocking to the location, which Cerreta renamed the One World Café in 2003. Three years later she was granted nonprofit status, and as word of her venture spread, people around the country began approaching her for advice about setting up their own pay-what-you-can cafés. The first were Libby and Brad Birky, a Colorado couple who had long volunteered at local soup kitchens and food banks but wanted to do more. Their SAME (So All May Eat) Café, which has as its motto “good food for the greater good,” opened in 2006. It was followed in later years by dozens of others across the country; there are currently some 50 cafés based on Cerreta’s model. Bob Pearson, the chairman of OWEE, estimates that at any given time there are 10 to 20 more cafés in the planning stages.

Cerreta now spends her time advising any group that requests her expertise (her original café has since closed to allow for this); she asks for no payment beyond travel expenses. “I do not own the idea of community cafés,” she says with characteristic unpretentiousness. “I do feel a deep stewardship, however, and I am thrilled that it has germinated and spread.”

Serving Up a Model Based on Experience

To help spread the idea further, One World Everybody Eats holds an annual summit with the 2016 event scheduled for January 16–18, in Denver, Colorado. OWEE also has a guide to starting a community café, “Spirit in Business,” available on its website. In it Cerreta writes, “Setting up a community café might feel to you like you are jumping off the rim of the Grand Canyon. I know that is how I felt when I first started and I was sure I would splat at the bottom. But now that I and others have done it, I suggest you take the leap. We are at the bottom looking up at you. Our experience can be your safety net. We have done it and have proved it can work.” She encourages those who are interested to build a strong team and engage with the wider community before opening. “Simply put, all roads lead to community,” she asserts, “and with strong ties in place you can overcome any obstacle or solve any problem you might face.”

Cerreta puts forth seven key precepts that she hopes those launching community cafés will follow. In addition to allowing each customer to set his or her own price for a meal and allowing patrons to volunteer in exchange for the food (a “hand up, not a hand out,” as she says), Cerreta feels strongly that diners should be able to choose their own portion size; that everything served should be healthy and seasonal; that all volunteers—both those working to pay for their meals and those who simply want to support the café’s mission—should be used to the greatest extent possible; that any paid staff should earn a living wage; and that each establishment should have at least one larger table where individuals and small groups can sit with others in order to cross social, economic, and other societal boundaries.

The SAME cafe in Denver features local artwork, like this still life that also features its name, So All May Eat.

Admittedly, naysayers have derided some of Cerreta’s goals; ultraconservative pundit Rush Limbaugh once famously deemed the notion of pay-what-you-can cafés “stupid” and “un-American” and called Cerreta and her cohorts “liberals playing games with the reality known as life.” Still, numerous establishments following her model are successfully alleviating food insecurity in their communities. The organization estimates that the currently existing cafés serve some 1.3 million meals a year.

The phrase “food insecurity” refers to a lack of access to enough food for an active, healthy life for all household members, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture. While it is often an invisible problem, it exists in every county in America. In 2013, government data showed that almost 50 million Americans lived in food insecure households.

Carefully Chosen Locations and Carefully Controlled Waste

For a community café to remain viable, most administrators agree that about 80 percent of its patrons must be able to pay the suggested cost of a meal, allowing the other 20 percent to eat for free or at a vastly reduced cost. That is possible if the location is chosen carefully, with an eye towards diversity and balance. Cerreta’s One World Café in Salt Lake City, for example, was in a central location with a college to the east, a downtown business area to the west, a relatively wealthy neighborhood just to the north, and one of the city’s poorest neighborhoods directly to the south. F.A.R.M. Café is located directly next to both a college and a popular vacation area, but is also right on a bus line, making it readily accessible to needier inhabitants of the region.

While becoming a self-sustaining enterprise is exponentially easier for cafés in thoughtfully chosen locations, those that are partnered with other organizations, such as churches or already established community groups, also tend to fare well. Mosaics Community Café, a soon-to-open café in Bartow, Florida, for example, is affiliated with Leland Family Ministries, a group that provides addiction counseling, job training for former inmates, nutrition education, and a host of other services. A pay-what-you-can eatery seemed like a natural fit to founder Libbie Combee, who struggled with addiction in her own past. “We can help someone kick a methamphetamine habit, get a job, and find housing,” she says, “and it is equally important to make sure they have access to healthy, satisfying food served in a dignified environment.” Because her group has been around for almost two decades and has deep roots in the community, Combee was able to call on a host of local resources—including a newly formed advisory board comprised of skilled chefs—for help.

The SAME cafe looks like any other restaurant and even offers outside seating.

Cerreta firmly believes in mining the community for such help. “It is funny that some people have extra money, some have extra property, some have skills, and some have good noses for great stuff. We value everything we get,” she says. “And reaching out to others reinforces our interconnectedness in a meaningful way.”

Successful cafés not only make use of everything they are offered, whether it is surplus tomatoes from a friendly purveyor or chairs from a local restaurant that is being remodeled—they aggressively cut waste wherever possible. At One World Café, Cerreta recalls, she served approximately 150 meals a day, yet all of her food waste could fit into half of a five‐gallon bucket—and even that ended up in the compost bin rather than a landfill. That type of efficiency, she points out, can be achieved, in part, by allowing diners to choose portion sizes right for them. By broad consensus, it also takes a great deal of creativity on the part of those planning the meals. At SAME, according to Libby and Brad Birky, if a farmer donates a supply of greens, Brad, who runs the kitchen, will find a way to use those greens in one of the week’s soups, salads, or pizzas.

Healthy and Tasty Food

Whether it is soups, salads, pizzas, savory entrees, or elaborate desserts, it is undeniably the food that draws most patrons to community cafés. “One of our biggest hurdles as an organization has been to convince people that these cafés are very, very different from soup kitchens,” Bob Pearson explains, pointing to the fact that soup kitchens, while performing a valuable function, are sometimes forced to rely on food donations of dubious nutritional merit and taste. “Community cafés are real restaurants, simply with a different pricing model.”

Beth Davison, a professor of sociology at Appalachian State University, volunteers at F.A.R.M. (she jokes that washing dishes takes her back to her work-study days as a college student) and eats there frequently. She concurs with Pearson that a community café can provide as fine a dining experience as any res-taurant. “Renee Boughman, the executive chef at F.A.R.M., cooked at some of the most exclusive places in the region before coming here,” Davison says. “And she could easily work anywhere she chooses.” Along with all the other community café chefs, Boughman tries to use as many local and organic products as possible to make her meals both healthy and appealing.

Community cafés, like JBJ Soul Kitchen, are regular restaurants with different pricing models. The innovative template has spread, with some 50 cafés operating based on the mission-driven, pay-what-you-can principles.

Another chef, Robert DeVito, affectionately known as Vito to those he works with at A Better World Café in Highland Park, New Jersey, explains, “Everyone, no matter what their circumstances, absolutely deserves to have delicious, healthy food. I love knowing that I am feeding people things that not only taste great but are good for them.” A Better World Café is affiliated with a nonprofit called Elijah’s Promise, which runs a catering company; a small market with to-go meals, gelato, and gourmet products; a traditional soup kitchen; and a highly regarded culinary school. DeVito, whose specialty is Italian cuisine, is himself a graduate of the school. “You might not get rich cooking at a community café,” he says, “but I cannot think of anything more rewarding.”

As befits food prepared so artfully, most of the cafés are decorated in exceptionally appealing ways, with colorful murals or framed prints on the walls and tables set with real dinnerware, rather than disposable. It is a far cry, as Pearson asserted, from the sometimes bleak and institutional atmosphere of soup kitchens.

Rolling Up Their Sleeves

Washing all that dinnerware takes manpower, however, as do prepping the dozens of pounds of vegetables a chef might go through during a lunch service, weeding the gardens many cafés maintain, explaining the pay-what-you-can system to first-time diners, and a host of other vital tasks, both large and small. Luckily, volunteers are rarely in short supply. Cafés located near schools with culinary programs or degree offerings in nonprofit management and related fields can count on a steady stream of eager, young interns. Most cafés also boast a roster of devoted community members happy to roll up their sleeves even if they are able to cover the cost of their own meals. So vital is the role of the volunteer coordinator that in many cafés, it is one of the few paid positions.

Christina M. May is a public/nonprofit management expert and the author of the doctoral thesis The Pay-What-You-Can Nonprofit Restaurant Model: A Case Study. She points out that scheduling volunteer shifts and planning for back-up can be a complex task and that all volunteers require a certain amount of training. (Some show up figuring that anyone can wash dishes or chop vegetables and are surprised to find that they, like workers in any commercial kitchen, must learn about food safety practices and procedures.) Still, May writes in her dissertation, volunteerism is an important part of the community café ethos. In the course of conducting her research, she spoke to one manager who told her, “People want to participate, but they want to do it in a short period of time and they do not want the politics that come with some nonprofits. The purpose of pay-what-you-can cafés is broad enough that you do not have to stand for any philosophy. You do not have to believe in any doctrine. It does not matter what you think about the president or about Republicans or Democrats. You can just come and work with people, side by side, so that everyone can have enough to eat. It is so simple.” When new volunteers assert that they are joining in because they admire the pay-what-you-can “concept,” the manager has a ready response: “I always tell them, ‘It is not a concept. It is real. Look. It is happening. And you are participating.’”

‘Pop-Up Cafés’

It is easy to understand the enthusiasm surrounding the pay-what-you-can model, but equally easy to see how daunting the task of launching a community café can be. Cerreta asserts that no one has to dive off the edge of the proverbial Grand Canyon right away. She points to Fareground, an operation in Beacon, New York, where a reported half of all school children are eligible for free or reduced-price lunches, but where artist lofts rent for well over $1,000 a month. Fareground’s founders, who come from social work, nutrition, and public administration backgrounds, are not yet ready to open a permanent location. Instead, they mount a “pop-up” event once a month, using the kitchen and auditorium of a local community center. “While our aim is to find a permanent space and become a full-time operation in the future, this is providing us with a great trial run,” Tara Bernstein, one of the founders, says. “Besides, it is like having a wonderful party every month because in addition to serving great food, we plan fun activities like crafts for the kids and African drumming.”

Everyone Wants to Contribute Something

A local journalist once referred to Fareground as “occupy[ing] a joyful front line in the Food Revolution,” but it does not take hosting a pay-what-you-can meal even once a month to help fight for the same cause. Sometimes all it takes is planting a single row of potatoes.

Evenlight Eagles, a North Carolina-based leather artisan, is the primary caregiver for her 87-year-old grandfather. A longtime farmer, he taught her how to garden from an early age, and she used those skills to grow food for F.A.R.M. Café. “Everyone wants to contribute something,” she says. “Tending the café’s garden allowed me to do that even when I had no money to give.” Eagles’ daughter, now 10, has eagerly pitched in with her mother, proving, it seems, that even the youngest person can harbor a similar desire to be of service. At the other end of the age spectrum is her grandfather, who has worked the soil of Appalachia for more than half a century. Last year he planted an extra row of potatoes to donate to the café.

The café gardens, such as the one at JBJ Soul Kitchen, are often tended, harvested, and pruned by volunteers, delivering fresh and healthy ingredients to the kitchen. The gardens offer a unique volunteer opportunity, allowing patrons to contribute, regardless of their ability to pay.

Even high-profile organizations such as the Jon Bon Jovi Soul Foundation want to contribute. JBJ Soul Kitchen, in the town of Red Bank, New Jersey was launched in 2009. Housed in a remodeled automotive shop, the cheerfully decorated spot, fronted by a thriving garden of herbs and vegetables, draws constant crowds.

Linda Pacotti, a retired government affairs specialist from the nearby town of Neptune, admits that she ate at Soul Kitchen for the first time hoping that the musician might be in attendance. Although he is known to visit on occasion, she has not yet caught a glimpse of him. “That quickly ceased to be important though,” she says, explaining that she immediately became taken with the idea of community cafés and now patronizes Soul Kitchen regularly. She often brings friends along, seeking to introduce them to the pay-what-you-can movement. “I tell them that although the suggested price is $10, I am not letting them up from the table unless they leave at least $15 or $20.”

A far cry from the sometimes bleak layout and design of soup kitchens, community cafés are designed with the look and feel of typical restaurants. Some, like SAME Café, feature communal seating to foster conversation and discussion among patrons.

A National Chain Gets Involved