Publisher’s Note

Dear Reader,

We are excited to present the Summer 2013 issue of UNCENSORED, and we thank you for your interest in our publication, whether you have just discovered it or regularly follow our articles.

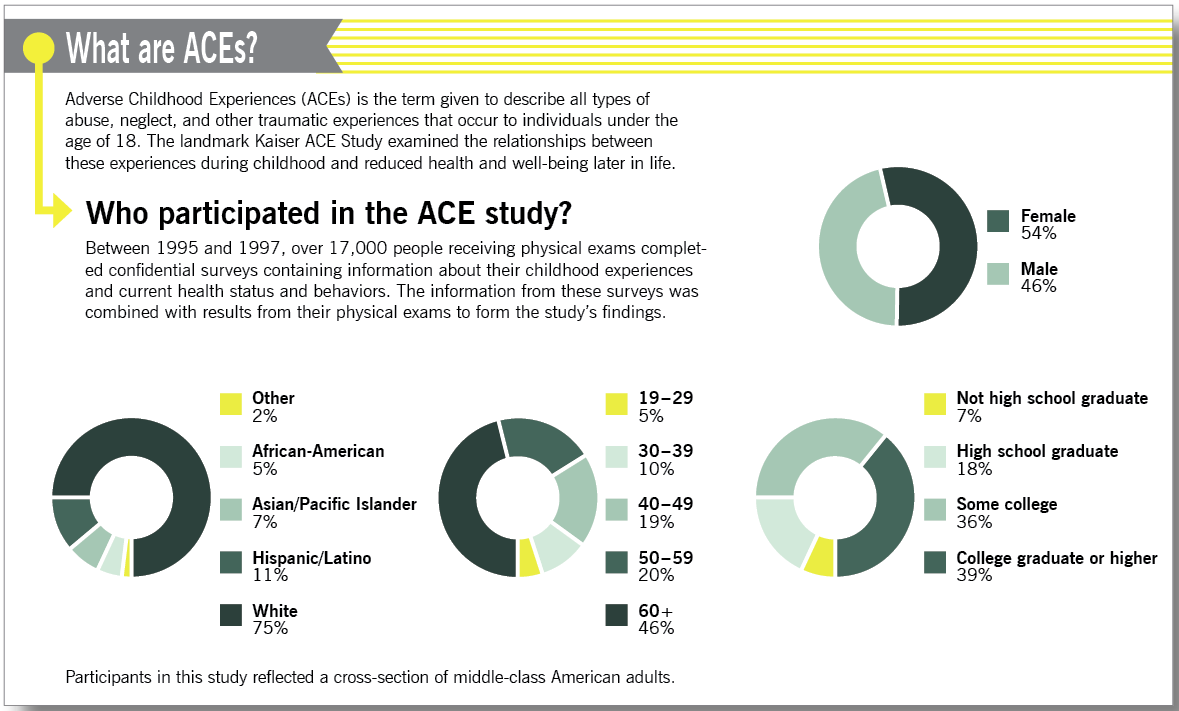

This issue’s on the Homefront section has a lot of food for thought. In “Conferring on Homelessness,” ICPH staff members explore timely topics in the world of homeless services—from the plight of homeless female veterans to a campaign to help destitute families hold on to personal property they lose after falling behind on storage payments. The essay on the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study reveals the long-lasting effects of childhood trauma, and our National Perspective article paints a sobering picture of the experiences of homeless Hispanic families.

The features in this issue offer something special as well. In “Beyond Freedom,” a moving follow-up to our Fall 2012 feature “The Unlikely Homeless,” Pearl Brownstein describes the supportive atmosphere at meetings of those who have escaped domestic violence. “It Takes McCarver to Raise a Child” looks at an innovative practice of the Tacoma Housing Authority, which has partnered with parents in a promising effort to keep families housed, improve children’s education, and invest in a local school.

Our Historical Perspective essay tracks the evolution of charitable summer camps, and our Voices column is devoted to the subject of rapid re-housing.

We at UNCENSORED welcome your comments and suggestions as we continue the conversation about the struggles of impoverished and homeless men, women, and children.

Sincerely,

Ralph da Costa Nunez, PhD, Publisher

President and CEO, Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

It Takes McCarver to Raise a Child:

The Tacoma Housing Authority’s Education-Based Fight against Homelessness

by Diana Scholl

Juilianne, Levi, and Malchi Torrella were accustomed to moving around a lot. “There was one school we went to for only six months, so I never tried to make any friends because I knew we were going to be moving again,” says Malchi, age nine.

The Torrellas are not military brats; they are not children of farmworkers or of parents with any other jobs that require relocation. The Torrella children were transient because of poverty and homelessness. And they were typical of students at McCarver Elementary School. The school has a warm environment, a gregarious principal, passionate educators, and a well-behaved, racially diverse student body of 465. But McCarver, located in the economically depressed neighborhood of Hilltop, has the highest poverty rate of any elementary school in Tacoma, Washington. In 2010 its student-turnover rate was 107 percent. (This was actually an improvement over the 2005–06 school year, when the figure was 179 percent.)

Two years ago the Torrella children would very likely have contributed to the school’s turnover. They were attending McCarver when their father, Alex, was released from prison. “I got out, my wife told me we were getting divorced, and I had the kids. I had a one-bedroom”—which was too small for him and the children—“and couldn’t live there,” Alex remembers. “I was basically homeless. I didn’t know what I was going to do. But then the lady in charge of the [rental] property told me about the project.”

She was referring to the McCarver Elementary School Initiative. Starting in 2011 the Tacoma Housing Authority (THA) gave five-year housing vouchers to 50 families whose children were students at McCarver Elementary School—families who were homeless or on the verge of becoming so. As with many voucher programs, the amount of rental assistance the family receives decreases over the course of five years, in order to promote self-sufficiency.

A student passes lockers at McCarver Elementary School, where a partnership between families and the Tacoma Housing Authority has shown promising results.

The parents also signed a pledge that they would commit to focusing on both their children’s education and their own. The program tracks parents’ participation in various activities—including helping with the children’s homework and being involved with the PTA—as well as their success at reaching certain benchmarks, such as earning diplomas and finding employment. The McCarver initiative provides these families with intensive support, including two full-time THA caseworkers who have an office in the school. The students in the program also receive additional help whenever needed, from backpacks to a summer program supported by private partners.

Many housing programs provide caseworkers and additional support. What makes THA’s pilot project different from other housing programs is that parents stay eligible for the voucher only as long as they keep their children enrolled in McCarver Elementary School. At a time when charter schools and private-school voucher programs are in vogue, for a housing authority to invest in a public school this way is highly unusual.

A more common approach to fixing a failing school would be to “give 50 families vouchers so they can escape so they can find themselves another school,” as THA’s executive director, Michael Mirra, explains. “Some of them might have done that, and that might have improved their families’ prospects. But those families would have been replaced by 50 families from the shelters, and nothing about that school would change. Our education project has two goals that are different. One is to improve the education outcomes of children we serve. And maybe we would have done that by giving 50 vouchers. But that would have done nothing for the second goal: to improve school outcomes. The McCarver project is focused as much on the school as it is on the children.”

The project is being carried out in conjunction with Tacoma Public Schools, which is also investing heavily in McCarver. The enthusiastic principal, Scott Rich, and energetic McKinney-Vento liaison and counselor, Carol Ramm-Gramenz, oversee the program’s day-to-day operations. barAt the request of the THA, the school district is undertaking a three-year process of turning McCarver’s curriculum into an International Baccalaureate Program, as a way of upping academic standards.

Ramm-Gramenz says, “It takes McCarver to raise a child.”

Using Housing for Educational Change

While THA has had partnerships with the school district before, they became more extensive when Mirra was named THA’s executive director, in 2004.

“The feeling before was, ‘We’re not social workers, we’re landlords,’” recalls Nancy Vignec, THA’s director of community services, a former teacher and a longtime THA staffer.

But Mirra is an activist in technocrat’s clothes. He wanted to use the housing authority’s status as landlord to many of the city’s low-income residents to create broader educational opportunities for the families THA serves—thereby breaking the cycle of poverty.

David McMullan, who once struggled with drug addiction, and his son, D.J., are successful participants in the McCarver Elementary School Initiative.

“I think of THA as a social-justice organization with a technical mission,” Mirra says. “If we mean to alleviate the poverty of the people we serve, education is really the solution.

“We started this education experiment with a couple of surmises. Except for the school district and the public-assistance office, the THA serves more poor children than anyone in the city. We are already deep into these families’ lives. We are their landlord, we manage these exquisitely regulated housing-assistance programs, we provide community services. That positions us to have influence. The surmise is that we can influence educational outcomes. The educational project means to find out how, and then to exercise that influence,” Mirra says.

Some of these educational fixes are as simple as giving out free books to every child who visits THA’s brightly colored offices. But the most ambitious experiment is the McCarver Elementary School Initiative.

“This isn’t a Band-Aid. It’s actually a cure.”

The project is funded by a number of sources, including the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Pierce County, the Seattle-based nonprofit organization Building Changes, and the Sequoia Foundation, as well as THA. The largest funder is HUD. In 2010 THA became a “moving-to-work housing authority,” which is a status HUD gives to 40 housing authorities. Rather than bringing more federal money, this designation allows THA flexibility in spending what it already receives. This made the McCarver Elementary School Initiative possible.

According to Vignec, “The McCarver Project proposal was a really central part to our original application to HUD and caught HUD’s eye.”

How to Measure Success

Mirra recruited former Tacoma Public Schools superintendent Michael Power to execute the McCarver Elementary School Initiative and, along with an outside contractor, design evaluation metrics and goals.

At the first yearly assessment, in 2012, the results looked promising. Because of the strongly encouraged participation of parents taking part in the initiative, the school had an active PTA for the first time anyone could remember. Families benefited from increases in education levels, job training, employment, and household income, with 13 more parents working than before the program started. Students in the project saw a 22 percent improvement in test scores—three times more than those in similar schools and cohorts. And while turnover at McCarver still remained extremely high, at 96.6 percent in the 2011–12 school year, it was down from the previous year’s rate of 107.4 percent. Among project participants the turnover rate was only 4.5 percent. School personnel say that this stability has done wonders for McCarver.

The McKinney-Vento liaison and counselor Carol Ramm-Gramenz helps oversee the McCarver initiative’s day-to-day operations.

“So often at the end of the school year, students don’t know if they’re coming back or not, and there’s really a collective sense of grief, for children as well as staff,” says Ramm-Gramenz. “Without the project, I’m sure a lot of those families would have been gone. But I really felt this last year for once there was a group of kids who absolutely knew they were coming back to McCarver. We were able to see them through the summer at the summer programs. It was just seamless as far as their progression to the next year. Having the sense of ‘I don’t know what’s going to happen next,’ of course they’re going to act out. This isn’t a Band-Aid. It’s actually a cure.”

Fourth- and fifth-grade math teacher Megan Nelson notes that having more stability in the student body has improved her classroom, with students more engaged and focused.

“It was really nice that when I did my report cards in the fall, there were the same kids in the winter. As a community it’s better when it’s stable,” she says. “And the parents are the most involved [they have] been. We had the first book fair in the first time anyone can remember.”

The students participating in the project are happier, too. Nelson’s student Juilianne Torrella, age ten, explains, “It was an often thing to move every half a year. But now we’re not moving. I like it because I still have all my old friends and don’t have to make new friends.”

Success Story

One success story is that of David and D.J. McMullan. David has had custody of his son, D.J., now eight, since the boy was very small. Their one-bedroom apartment is papered with pictures of D.J., and one wall is covered with his awards.

When D.J. was younger David struggled with an addiction to methamphetamine, which left him toothless, unemployed, and unable to care for his son. “It’s not that I was a bad dad, I just got caught up in it,” David says. D.J.’s mother is out of the picture, and D.J. was put in foster care for two years. Determined to get his son back, David enrolled in a drug- and alcohol-treatment program and visited his son in foster care every week without fail.

Once clean, he got his son back and enrolled him in McCarver Elementary School. Then the two joined the school’s project. “The program has made my life structured. Anything I really need I can go to them for,” he says. The support has included everything from help with resume writing, to enrollment in school to become a fleet mechanic, to a new set of dishes, to help with paying $2,000 in electric bills, to dentures.

David is optimistic that he will be employed and self-sufficient soon. “If I’m not self-sufficient at the end of the program, there’s a deeper problem,” he says.

Obstacles

For many parents in the program, like many poor parents overall, there are deeper problems, and finding employment for them has been one of the biggest challenges of the McCarver initiative so far.

An important part of the McCarver initiative is to involve students’ parents in the education process.

“We have to be very resourceful,” THA caseworker Sharon Fletcher Jackson notes. “Just in the economic climate we have, even for someone who has a high school or college education it can be difficult. But there are families with legal problems and employment barriers. It’s more difficult for that population.”

The caseworkers put a lot of effort into addressing these employment and legal problems. They also work to make life as easy as possible for the families. The school has invested extra resources in these families and is attempting to improve academic performance across the board. With five years free from the threat of eviction, families can better focus on these other concerns.

Trial and Error

In one fifth-grade classroom at McCarver, students tried to get a fan to move a paper boat. In the process of trial and error, the engaged and determined students were making changes to their experiment. The teacher, Ms. Haase, told her class, “Make sure you only change one thing at a time. If you change two things, you won’t know which made the difference.”

Considering that advice as it applied to a larger experiment—the McCarver Elementary School Initiative—Power observed, “We are changing so many things but don’t know what’s helping. There may be some point in the future where another school wants to replicate our success, but only has half the funding. It will be difficult to say, ‘Here’s what really worked, and here’s what was just a nice extra.’ But we don’t care as long as it’s working.”

And McCarver is being looked at as a model. Educational liaisons for housing authorities across the United States have visited the school, hopeful for success they can emulate. Power is cautious of moving too quickly but says that so far, the results have been promising.

The Torrellas

The Torrellas serve as an example of what the McCarver initiative can accomplish. The children have flourished in school, and their father has been active with the PTA. “Everyone at school knows Alex,” he says with a laugh. Alex has remarried; his bride’s son also attends McCarver and benefits from the program.

In addition, with the encouragement of his caseworker, Carlena Allen, Alex started his own company.

The Tacoma Housing Authority’s innovations include giving free books to children who visit the office and providing parents with easy access to information.

“The way I started off was, the caseworkers were moving offices, and I had a lot of time on my hands, so I helped them move furniture. Carlena said, ‘You should be a handyman.’ That planted the seed. You can only go so far looking for work. I’ve been busy nonstop,” he says.

By Alex’s account, he has become less dependent on the program. “You have to progress with everything you do, from raising the children, to being gainfully employed and all the steps that are required,” he says. “The one thing I learned is, if you communicate all the time, they will help you.”

Resources

McCarver Elementary School; Tacoma, WA ■ Tacoma Housing Authority; Tacoma, WA ■ Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation; Seattle, WA ■ Pierce County; Tacoma, WA ■ Building Changes; Seattle, WA ■ Sequoia Foundation; La Jolla, CA ■ U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development; Washington, DC ■ Tacoma Public Schools; Tacoma, WA.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

Beyond Freedom:

Survivors of Domestic Violence Learn Self-Care

by Pearl Brownstein

In the article “The Unlikely Homeless: One Woman’s Experience in a Domestic–violence Shelter,” published in the Fall 2012 issue of UNCENSORED, Pearl Brownstein wrote about what led her to seek shelter and about the value of her time there. In this article Brownstein describes a post-shelter support group for DV survivors.

From my apartment in the far corners of Brooklyn, it takes approximately an hour and a half to get to “Beyond Freedom,” and that’s if I get an express train. My weekly journey, which involves toting my 17-month-old son in his stroller up and down the subway stairs, is not unlike those of the other women who attend Beyond Freedom meetings with me—most of them residing in shelters with their families in far less desirable areas. We all come from far away, be it the outer reaches of Brooklyn, the Bronx, or Queens, and yet every Friday from 11:00 a.m. to 12:30 p.m. we manage to converge in the Freedom House community room. As my son and I walk through the building’s sliding double doors, we are immediately welcomed by staff, who still remember our names, even though we no longer reside here; it has been nearly a year since we became residents at this domestic-violence (DV) shelter serving survivors and their families.

The premise of Beyond Freedom began as a simple one: bring DV survivors together on a weekly basis to share their feelings and experiences. Through sharing, an emotional release occurs, as does the possibility of relating to others, making friends, forming a network, and becoming inspired.

Beyond Freedom participants place their hands on the drums they play during meetings. Playing drums provides mutual encouragement and emotional release.

During the hour-and-a-half meetings, our sons and daughters are placed in child care down the hall, and because they are already familiar with the shelter staff, the time apart from their moms is not one of tantrums and longing, but of shared play and fun. For the mothers, time away from our children is crucial, as a majority of us are stay-at-home single moms. This brief weekly respite from the constant demands of mothering is a huge relief and gives all of us the opportunity to focus on ourselves and speak our minds.

We each sit in one of the chairs that form a circle in the center of the room, with bongos in the center of the circle.

Drumming is an integral part of the Beyond Freedom meetings, serving as another method for self-expression and emotional release. Meetings typically start with a round-robin of check-ins, or “shares,” each beginning with one’s name and discharge date from Freedom House and concluding with an accomplishment for that week. Although the bongos usually sit unused until the last few minutes of the meetings, when we’re particularly enthusiastic about one of the shares, the beating of our hands on the tight goatskin becomes a form of exclamation and a way of relaying our congratulations. After each share, the facilitator provides feedback and suggestions on self-care, parenting, and planning for the future. There are refreshments, including coffee, juice, yogurt, and pastries—and sometimes a special treat of fried chicken served with hot sauce.

After the DV Shelter

Beyond Freedom has been up and running for less than two years. “It’s a support group,” Freedom House’s associate director, Vanessa, tells me plainly. (For privacy and safety purposes, most of the names of the people mentioned in this article have been changed.) “For people coming out of DV shelters, support is imperative. We realized that we needed a service in place that’s readily available for women and their children.” Vanessa goes on to mention the need for women to protect themselves in a variety of ways after escaping domestic violence. “During our meetings,” she says, “we always try to weave in a discussion on the importance of safety in relationships, at home and in the workplace, in managing your Facebook profile and cell phone appropriately—always making sure your GPS is turned off—as well as finances, such as keeping your bank account secure. It’s a complete change of lifestyle. It’s changing the way that you live.”

For most people, breaking the cycle of abuse doesn’t happen overnight; the possibility for change has to be ingrained, and it takes time—not only for the women who have experienced the abuse, but for their children, too. “If you are a child of domestic violence,” Vanessa explains, “the trauma you experienced impacts you when you become an adult. That’s why we talk about breaking the cycle now. A little girl doesn’t have to be controlled and degraded. A little boy can be taught to treat girls with respect. When the DV system first started out, the social services were just for women, until people started realizing that the abuse also affected the children.”

“Coming into shelter is traumatic enough—but the other crisis is when they have to leave here. We wanted after-care services for those who are getting ready to go or have already left.”

While at Freedom House, residents and children benefit from individual counseling, group counseling, and tight security, but when a family’s stay is maxed out after 135 days, those services inevitably come to an end. “We were concerned about what happens to families afterward,” Vanessa says. “Coming into shelter is traumatic enough—but the other crisis is when they have to leave here. We wanted after-care services for those who are getting ready to go or have already left. We knew it was important, and even though we didn’t have funding for Beyond Freedom, we decided to do it anyway.”

After discharge, a majority of women and their families go to the Prevention Assistance and Temporary Housing (PATH) office. Located in the Bronx, the PATH office is where New York City families with children are evaluated for eligibility for shelter and assigned shelter placements within the five boroughs. At this point, without services for DV survivors, many families can quickly become isolated or, in the worst-case scenarios, return to their abusers. Understanding this, Freedom House established Beyond Freedom as a mandatory program for all residents to attend in their final month prior to discharge, in preparation for their lives ahead, and with an open invitation to continue attending meetings after they leave.

The facilitator of Beyond Freedom is Rebecca, a domestic-violence survivor, poet, and musician who runs Freedom House’s popular drumming circle and potluck dinner every Sunday afternoon. “In choosing a facilitator,” she tells me, “Freedom House wanted someone who was a survivor, who was also an advocate and activist in domestic violence and homelessness, and who believes, as I do, that the arts—drumming and theater in particular—can instigate healing. The fact that I am a survivor offers the women hope that they won’t always be receiving aid, and that they should strive to make a livable wage.”

That is easier said than done for a majority of survivors, as many cannot find work that will support them, let alone their children. The city’s homeless population continues to swell, and with sustained funding cuts for various low-income housing programs, working one’s way up to self-sufficiency is challenging at best. In April 2012 the city stopped providing housing subsidies to homeless families and domestic-violence victims. A shortage of public housing is also a national concern, as there was a 700,000-unit decrease between 1995 and 2009, due to expired contracts and conversion to market-value rentals, according to a 2011 report from the Joint Center for Housing Studies at Harvard University. As rental costs become increasingly steep in the New York metropolitan area, it is not uncommon to spend at least half of one’s salary on keeping a roof overhead—if one can even manage to move beyond shelter, which is a huge accomplishment in itself. According to a 2012 editorial in the New York Times, 8.5 million very-low-income families without housing assistance paid more than half their incomes on housing in 2011—an increase of 47 percent from 2007. Often, people struggle after leaving the system to such an extent that they wind up back at PATH. A 2012 report by the Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness, A New Path: An Immediate Plan to Reduce Family Homelessness, cites that nearly 50 percent of families who seek temporary shelter in New York City have had at least one prior shelter stay.

Artwork adorns the walls of the Freedom House community room.

“When I was going through shelter,” Rebecca tells me, “there wasn’t anything like Beyond Freedom. First and foremost, we’re trying to prevent women from becoming homeless again. We’re empowering women to stand up for themselves through the use of journaling their feelings and experiences, by stressing the importance of maintaining strong boundaries and being aware of and acknowledging red flags. By using these tools, which for many women are completely new, their self-esteem naturally becomes elevated and in the process they become stronger. … We’re looking at self-care, and we’re looking at safety as a lifestyle rather than a moment in time when a woman and her family resided in a DV shelter.”

With a penchant for thinking outside the box, Rebecca has some big ideas that differ widely from the city’s methods for dealing with homelessness. “What we need to do,” she says, “is work toward home ownership. If we become homeowners, one house at a time, we can create the change ourselves. We need to find funders who are willing to purchase below-market multifamily dwellings. We can then rent out one of the apartments to pay off the mortgage, and rent the other apartment at an affordable price to a survivor and her family.”

Reminders to Nurture Ourselves

Vanessa is the co-facilitator of Beyond Freedom. Paul, the CEO of the nonprofit organization Barrier Free Living, of which Freedom House is a program, also occasionally attends; when introducing himself to the group he says repeatedly with a smile, “I’m here to listen and to learn from all of you, so that I can be a better advocate for what you need.” In addition to supporting former residents, the Freedom House staff hopes that by tracking survivors’ experiences they might be able to demonstrate the need for increased funding for necessary programs and, on an even larger scale, initiate policy change.

At a Beyond Freedom meeting, Lorna shares with the group that she isn’t eating properly. I nod my head in understanding, as I too am having a problem with my appetite. We joke about having bought new belts that we’ve buckled in the last hole to make our sagging jeans fit. During our stay at Freedom House, Lorna and I, who have sons born one year apart, lived in studios across the hall from each other. We have both lost 15 pounds since we entered shelter, which Rebecca says is common for women who have been traumatized by DV: “Oftentimes, a woman will focus on caring for and feeding her children, and forget to care for herself.” As a holiday gift to each Beyond Freedom attendee, Rebecca provided a plate, bowl, and drinking glass as a reminder to nurture ourselves. “It’s important for the children to see their mothers eat well,” Rebecca says, “and what better way than to do so on special plates and bowls that remind them of the self-care tools they learn about at Beyond Freedom.”

On display in the Beyond Freedom meeting room are the boots and handbag worn by a facilitator when she escaped her abuser. The items symbolize freedom and strength.

Another former resident, Tania, who is a mother of three, reports to the group that she received all A’s for the college classes she took the previous semester. She says that she hopes to become a social worker and help other women who are making the transition to independence after leaving their abusers. When she finishes sharing, we all applaud and beat on our bongo drums.

Stephanie, a mother of two who originally hails from the Caribbean, announces that she just began a ten-week self-care program for women, which includes personal training lessons at a free gym and classes in meditation. She is also studying for her GED. More applause and drumming ensue.

During these meetings there is never talk of violence—I have never once heard a lurid story of blood or bruises, broken bones or visits to the emergency room. Nobody talks about their abusers or what it was like living with daily physical, economic, or emotional abuse. I chalk it up to the fact that we are living as well as we can in the present and letting go of the past.

I share with the group that I am looking for well-paying full-time work so that my son and I can move to a neighborhood with better schools. In the meantime, I manage to support us with various freelance projects, and somehow we break even every month. With each passing week that I am no longer a resident—I left Freedom House approximately seven months ago—I see that I have many more possibilities than the other women, a majority of whom continue to live in shelter and rely on food stamps and Medicaid. I live in my own apartment; I have college and post-graduate degrees; my son’s father provides steady child support and a healthy percentage of child-care expenses; and I have prior work experience as well as some savings. At the same time, my career has never been particularly lucrative, and I know that without my advantages I would be living on the edge. According to a recent editorial in The Nation, more than half of single-mother households find themselves below the poverty line.

When I ask Vanessa what the biggest hurdle is for women leaving shelter, she says quickly, “Finances and child care.” She continues, “If a woman doesn’t have appropriate child care, how can she find employment? But if she’s not making enough money to pay for a sitter, if she doesn’t have that security, she can’t make a step forward.”

When I ask Vanessa what the biggest hurdle is for women leaving shelter, she says quickly, “Finances and child care.” She continues, “If a woman doesn’t have appropriate child care, how can she find employment? But if she’s not making enough money to pay for a sitter, if she doesn’t have that security, she can’t make a step forward.” Hearing these words, I am reminded that I am not all that different from Stephanie and Tania, who sit on either side of me. Prior to this Beyond Freedom meeting, I did some math to decide whether it was worth it to put my son in child care the following week while I look for more work. Would my job-seeking bear enough fruit to pay for those hours with a sitter? I couldn’t be sure.

The biggest hurdle for the growth of Freedom House is funding as well. “My wish would be to really expand our after-care services,” Vanessa tells me, “but in order to do that you need extra staff—a supervisor and social workers to provide the advocacy for people who need it and the continuation of support. We just don’t have the funding.”

Even without funding, the Beyond Freedom program has grown so popular that it has split into two groups, with Spanish speakers meeting on Thursdays and the English speakers getting together on Fridays. Despite the long distances that I and the other women travel to attend, when another Friday rolls around we always decide that it’s well worth it to make the journey yet again. Vanessa tells me that a few days before a snowstorm was expected, she called all of the Spanish speakers to tell them that Beyond Freedom was canceled for that Thursday; everyone showed up anyway, acting as if they had never received her message. “It was a lesson for me to see how much they really need to be here,” Vanessa says, “and how important these meetings are to them.”

On Valentine’s Day a special guest was welcomed to the group: Beluchi Jeanot, a makeup artist from the nonprofit organization Project Papillon, whose mission is to improve the self-esteem of homeless female victims of domestic violence. Beluchi tirelessly made up the faces of 18 former residents as well as shelter staff, applying false eyelashes, lipstick, rouge, and shadow. In the process he managed to bring out everyone’s inherent beauty, which is often hidden beneath masks of stress and anxiety. It is hoped that someone from Project Papillon will come to Beyond Freedom regularly.

“Beluchi told everyone that he wasn’t putting makeup on them so that they could go out and look cute,” Vanessa says. “More than anything, it’s about feeling good inside by making your outside look good. It’s about boosting self-esteem.” The development of self-esteem, which the Freedom House staff emphasizes continually, is extremely important after women have been tyrannized and beaten down in physically and emotionally abusive relationships. Poor self-esteem, my Freedom House social worker reminded me repeatedly, is often what causes women to choose unhealthy relationships in the first place.

Beyond Freedom appears to be expanding in other ways, too, as it continues to invite guests from outside the group. The next visitor will be Marcella Goheen, whose acclaimed one-woman show, The Maria Project, uncovers a particularly gruesome act of domestic violence that was a secret in Goheen’s family for generations. Marcella will lead a six-week intensive program called “Codes of Hope,” which will involve collecting survivors’ stories and will culminate in a handbook of participants’ writings. For many of the women who attend Beyond Freedom, this will be the first time they have put pen to paper about their personal lives and why they sought shelter at Freedom House. The process of self-expression promises to be both a creative and cathartic experience.

The Beyond Freedom meetings always go by quickly, and for the last few minutes we are encouraged to take part in a drumming circle, which is initially led by Rebecca. The unified mimicking of her beat brings us all together even more than the sharing we have just completed. After following Rebecca’s rhythm, each of us leads the group with a rhythm of her own.

As I beat on my drum, I think about my son, who that morning walked unsteadily through the doors into the Freedom House lobby. My social worker, who first met my son when he was seven months old and not yet crawling, exclaimed, “Wow—look at him go! I remember when he was half that size!” A similar growth, we hope, is occurring inside all of us who attend the Beyond Freedom meetings. As we bear witness to our personal transformations, I see firsthand that we all, in our own ways and despite the odds, are flourishing. At the end of our meetings, I already look forward to the following week, when I will surely hear—and tell—stories about grit, perseverance, and triumphs that are both small and large.

Resources

Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness; New York, NY ■ Barrier Free Living; New York, NY ■ Project Papillon; New York, NY ■ Joint Center for Housing Studies, Harvard University; Cambridge, MA.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

The Historical Perspective—

Fresh Air for City Kids: The Early Years of Summer Camp

by Ethan G. Sribnick and Sara Johnsen

“Thank you very much for sending me out here,” a New York City boy wrote from summer camp in 1910. “We sleep in open air tents. We had a picnic Thursday and I won a prize, we are also going to have one Monday. We are always playing ball out here … we pick blackberries and people give us pears and apples.” Similar descriptions of country life can be found in thousands of letters from campers each summer. But this young New Yorker was not writing to his parents; instead, he was thanking a sponsor whose donation had paid for him, along with a group of other poor children from his neighborhood, to attend summer camp.

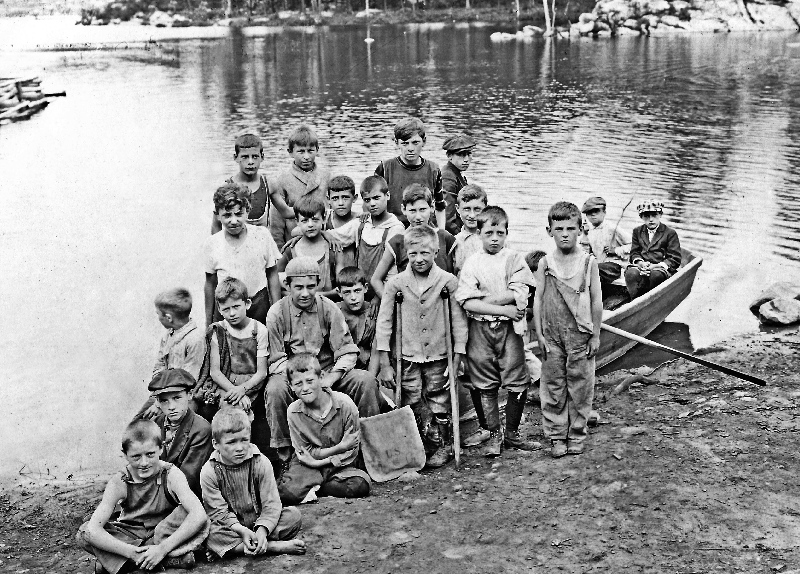

Charitable summer camps for poor children first opened in the U.S. in the 1870s and have operated every year since. Campers’ motivation for attending is not mysterious: they escape the city for a few weeks, play in nature, and make new friends. The motivation of adults running the camps, however, has evolved along with the goals of the social-services community and cultural attitudes toward the poor, the city, and rural life. Camps are still evolving. Exploring the history of camps for underserved children can help us better understand their role in promoting child welfare today.

Camp administrators tried to give poor children the leisure opportunities that their wealthier peers enjoyed. The small boys in this image—including one on crutches—wear tattered clothes and pose in front of idyllic Car Pond at Lake Stahahe in Harriman State Park. Courtesy of the Palisades Interstate Park Commission Archives.

By the end of the nineteenth century, the forces of immigration, urbanization, and industrialization had created deep rifts between the housing and lifestyle of the rich and those of the poor in New York City. Poor children usually spent the hot summer in overcrowded, poorly ventilated apartments. With no public parks to relieve the congestion of the neighborhoods, children played in dirty streets. Wealthy children, however, escaped with their families to country houses or were sent north to the modified wilderness of summer camp.

In 1877 the Reverend William Parsons, himself recently transplanted from the Lower East Side of Manhattan to Sherman, Pennsylvania, bemoaned the lack of outdoor leisure available to the children he had left behind in the city. That summer, Parsons placed about 60 children from Brooklyn slums with volunteer hosts among his new neighbors in rural Pennsylvania, where the children spent the summer playing outdoors and experiencing middle-class life. Parsons’s project, soon named the Fresh Air Fund, quickly took off. By 1888 the organization was sending more than 10,000 New York City children a year to live with host families throughout the Northeast.

Organizations with similar missions soon materialized around the country. A New York City businessman, William George, began his own fresh-air program, bringing children out to camps in the country rather than to hosts’ homes. In 1894 George organized these camps into what he called Junior Republics. Campers were supposed to develop leadership skills and a work ethic by earning food and lodging through their labor around the camp. In addition to this physical-labor regimen, George installed a system of self-governance within the camp: children served in the legislative, executive, and judiciary branches. These innovations were intended to introduce children to the middle-class economic and political values that George imagined they were missing in New York’s slums.

Eventually, Parsons’s Fresh Air Fund also opened camps as a way to provide a country experience for a greater number of children. As the fund reached out to more diverse groups of young people—including blacks and the children of recent Jewish and Catholic immigrants—finding willing hosts among the mostly white, Protestant middle class sometimes proved difficult. Camps provided an opportunity for these children to be exposed to country life while avoiding conflicts with hosts over religious, ethnic, or racial differences.

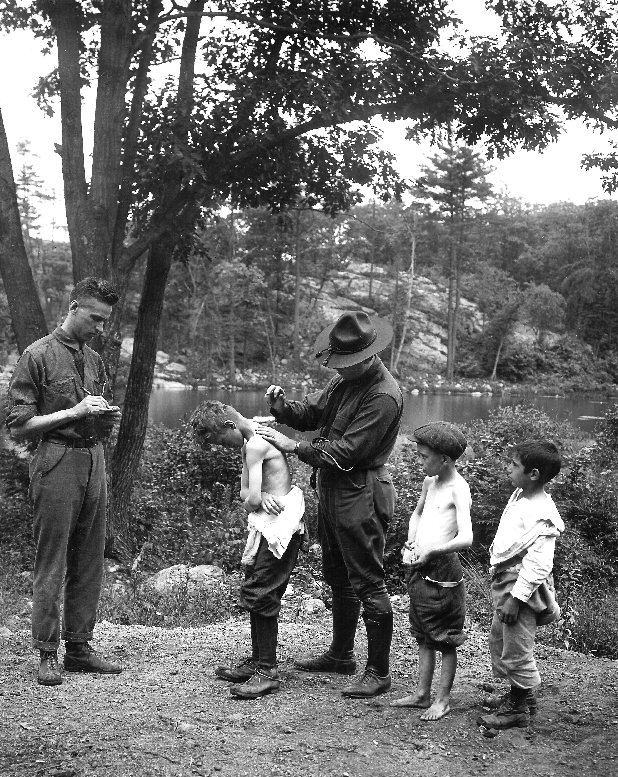

In a time when overcrowded, poor urban neighborhoods contributed to the spread of infectious disease, children’s removal from the city to summer camps served as an opportunity for medical care in addition to fresh air. Here, a doctor examines young boys at Lake Stahahe camp. Courtesy of the Palisades Interstate Park Commission Archives.

Summer camps became more popular in the early 1900s as educators rejected the rote memorization that characterized traditional learning and embraced the Progressive notion of learning by doing. In the first decade of the twentieth century, New York’s leading social-service organizations—the Charity Organization Society, the Association for Improving Conditions of the Poor, and many of the city’s settlement houses—all established their own camps. Lillian Wald, the leader of the Henry Street Settlement, framed the mission of these camps in the new scientific language of child development. “The possibility of giving direction at critical periods of character formation,” Wald explained, “particularly during adolescence, and of discovering clues to deep-lying causes of disturbance, makes country life a valuable extension of the organized work of the settlement.”

Middle-class concerns about public health served as a motivation for camps from the beginning: “fresh air” was a treatment for tuberculosis, which was rampant in tenement neighborhoods, as were cholera and polio. Camp administrators—and, in the case of the Fresh Air Fund, middle-class host families—wanted to improve tenement children’s health outcomes, but they were wary of possible transfer of disease from those children to camps and homes in the country. In order to guard against that, Fresh Air Fund representatives inspected children’s homes, investigated their medical records, and required that each child undergo two physical examinations. Once the children arrived at camp or at hosts’ homes, adults trained them to adhere to middle-class habits of cleanliness.

Early camps also aimed to introduce children to other conventions of the middle class. Fresh Air Fund camp counselors were disturbed, for example, by the food and drink that immigrant children consumed, such as coffee and organ meat. Instead, camp food included such classic American fare as jelly sandwiches, baked beans, beef stew, hot cocoa, and ginger snaps. “The offspring of the crowded city often utterly refuse to drink the milk, or eat the country delicacies,” one article on the Fresh Air Fund camps reported. “A day or two, however, generally straightens things out.” Altering the children’s taste in food was part of a larger project of Americanization. A visitor to a Fresh Air Fund camp in New Hampshire reported, “I could not have believed it possible, had I not seen, that the ‘Melting Pot’ could have done such effective work in so short a time. There was no evidence of any distinction of class, race, financial condition, or anything else.” By bringing children from different ethnic backgrounds together into a middle-class environment, administrators hoped to integrate children into the dominant culture.

The Fresh Air Fund refused to serve kosher meals, thereby excluding observant Jews from their camps, but even camps aimed at a single ethnic group engaged in programs of assimilation. At Surprise Lake, the Educational Alliance—a settlement house on the Lower East Side—ran one of the few kosher camps for New York City children. Still, more Americanized Jews complained that children wearing hats to meals gave the camp “a distinctly oriental flavor.” In the 1920s an invited lecturer instructed children in how to speak properly and how to sit with a “correct American posture.” An article in the camp newspaper, also from the 1920s, demanded that campers abandon Yiddish and instead “speak the English language, the language of America.” Camp leaders hoped that children would return to their parents not only physically cleaner and healthier but also scrubbed of some of the ethnic peculiarities that might hold them back in American society.

The men and women who organized early sleepaway camps for poor children acted on a variety of charitable and political impulses: a desire to promote the health of kids growing up in overcrowded, dirty cities, to allow them to enjoy nature and leisure, and to encourage assimilation into the middle class. As camps evolved during the twentieth century, administrators shifted emphasis away from Americanization and public health and toward play and leisure. Summer camp made vacations in nature possible for generations of urban children throughout the twentieth century, especially in New York City, where many social-service providers continued to operate summer sleepaway camps. But in the late 1980s recession and fiscal austerity forced many organizations to close or sell camps. Between 1985 and 1996, the number of nonprofit sleepaway camps decreased from 435 to 321—more than 25 percent—according to an estimate by the New York State Camp Directors Association.

A camp administrator inspects boys for neatness and posture c. 1923. Once children arrived at camp or at a host home, adults trained them to adhere to middle-class habits of cleanliness. Courtesy of the Palisades Interstate Park Commission Archives.

Despite a period of financial challenge and decline, there are still approximately 8,000 not-for-profit camps operating in the United States today, and the American Camping Association estimates that nearly one million children attend camp each summer with scholarship assistance. In the summer of 2011, Homes for the Homeless sent nearly 600 children, most of them homeless New Yorkers, to summer camps upstate. Homes for the Homeless—like the Fresh Air Fund and the Coalition for the Homeless—operates its camps in order to provide opportunities for fun and learning in nature. Since they were built, in the 1930s, the camps that Homes for the Homeless now runs have been dedicated to providing outdoor experiences for underserved youth. Connie Stine, the director of one of these camps and the grandchild of settlement workers who opened the camp in the 1930s, explains, “I see camp as a way to continue my grandparents’ legacy on the site that they founded. The children we are serving are very similar to the children that these camps have always served. And it’s just as valuable today as it was 30 or 40 or 70 years ago for children to have the opportunity to be out of the city, to be in a new environment where they can learn about nature and the wider world around them.”

But contemporary camps are also interested in measuring specific benefits for those who attend, such as improved social and problem-solving skills. Lance Ozier, a member of the American Camp Association National Committee for Advancement of Research and Evaluation, argues, “At camp, kids learn things like responsibility, self esteem is increased, they take on leadership opportunities, they take on experiences that allow them to cooperate and work with peers and adults in meaningful ways that they wouldn’t have an opportunity to do otherwise.”

Private and government funders have increasingly looked to not-for-profit groups to measure camps’ impact on learning and school achievement. Recent camp models have aimed to combat the educational achievement gap by lessening summer learning loss among low-income students. In July 2012 New York City and the Fund for Public Schools launched Summer Quest, a day camp that merges summer school and sleepaway camp models, offering students formal, traditional academic programs alongside curriculum-aligned camping trips, sports, and arts activities. Ozier notes that camps are “more crucial now than in the early days because school has become hyper-focused on academic skills, and there isn’t space for these non-cognitive, psychosocial skills that you just can’t learn from grammar exercises.”

The psychological and social benefits that children accrue from camp are difficult to quantify. But as policymakers and camp administrators work to develop programs that reflect the evolving concerns of the social-services world, campers will continue to learn and play in a natural environment that they might not otherwise have encountered.

Resources

Guarneri, Julia. “Changing Strategies for Child Welfare, Enduring Beliefs About Childhood: The Fresh Air Fund, 1877–1926.” Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era 11, no. 01 (2012): 27–70 ■ “History & Mission.” The Fresh Air Fund. ■ Ozier, Lance. “Camp as Educator: A Study of Summer Residential Camp as a Landscape for Learning and Living.” Teachers College, Columbia University, 2012 ■ “Camp as Educator: Lessons Learned from History.” The Camping Magazine. 83, no. 5 (2010): 20 ■ Paris, Leslie. Children’s Nature: The Rise of the American Summer Camp. New York: New York University Press, 2008 ■ Van Slyck, Abigail A. A Manufactured Wilderness: Summer Camps and the Shaping of American Youth, 1890 –1960. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2006 ■ Wald, Lillian D. The House on Henry Street. New York: H. Holt and Co., 1915.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

Voices—

Rapidly Re-Housing Homeless Families: New York City, a Case Study

by Ralph da Costa Nunez

Ralph da Costa Nunez, PhD, is the president and CEO of the Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness and the publisher of UNCENSORED.

A strategy known as “rapid re-housing/housing first” is currently heralded as the answer to reducing family homelessness. The concept is simple: move families immediately from shelter to permanent housing. The problem is thus solved; these families are no longer homeless. In municipalities and counties across the country, rapid re-housing is being implemented and declared an immediate success despite little long-term evidence to support this conclusion. Nowhere has this policy been practiced on such a large scale and for such an extended period of time as in New York City.

This report examines the model of “rapid re-housing/housing first” using New York City as a case study. It specifically examines the impact of this policy on the city’s shelter system for homeless families, focusing on shelter census, eligibility, and recidivism rates, along with length of stay and overall costs.

New York City Shelters

New York City currently houses more than 11,000 families with more than 20,000 children in city shelters.(1) In 2005 the city initiated rapid re-housing policies based on time-limited rental subsidies to foster permanent independent living for homeless families.(2) The prediction was that, after a limited period of time, rapidly re-housed families would become financially secure through employment and be able to maintain their living situations independent of temporary rental subsidies. In other words, instances of family homelessness resulted simply from short-term housing crises, and short-term rental subsidies would solve the problem.

For six years, beginning in the 2005 fiscal year and ending in 2011, rapid re-housing was at the heart of New York City’s effort to reduce family homelessness. Over that period some 33,000 families were moved out of shelter.(3) During that same period of time, however, the return-to-shelter rate increased significantly, indicating that lack of housing is not the only reason that people become homeless. Based on those numbers and the length of time the program was in place, it is possible to go beyond the qualitative rhetoric currently supporting rapid re-housing and quantitatively define the successes and limitations of this policy.

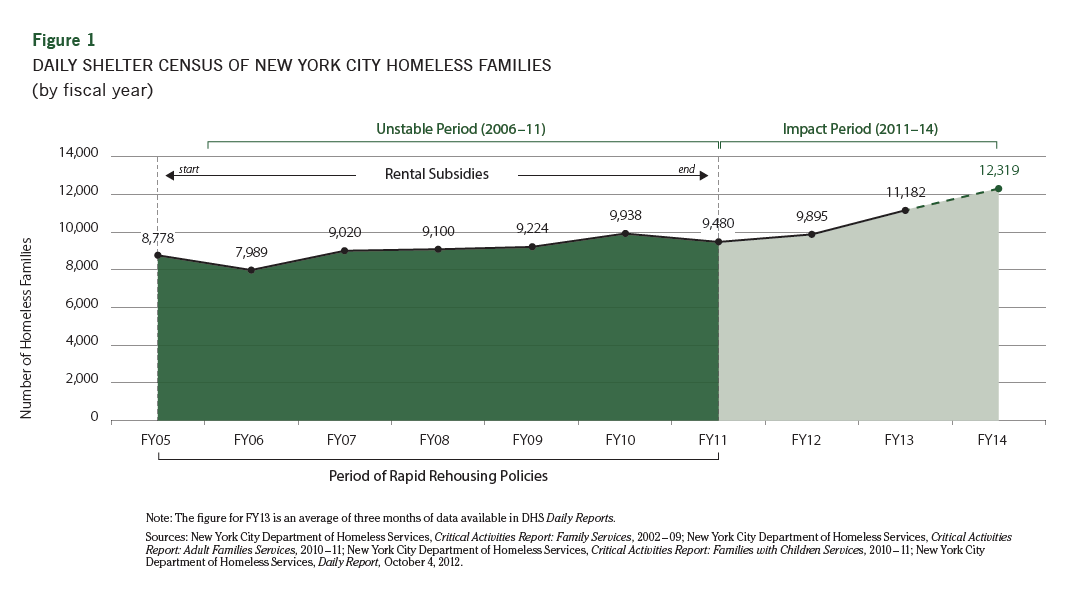

Shelter Census

Although designed to reduce family homelessness, rapid re-housing policies have actually had the opposite effect in New York City. By offering rental subsidies to sheltered families, government actually stimulated homelessness. Numerous families that were living doubled-up or in substandard housing saw an opportunity to secure new housing and entered the shelter system to get places in line. Between FY05 and FY11, when rental subsidies were in effect, the average annual census of families housed in city shelters increased 8%, to 9,480 (see Figure 1).(4) Even with the end of rental subsidies, in FY11, the number of homeless families in shelters continued to grow year-over-year: 4.4% in FY12, to 9,895, and 13% in mid-FY13, to 11,182. In all likelihood, families continuing to enter the shelter system are expecting and waiting for a new re-housing initiative to appear. Regardless, if this trend continues, the data projects that there will be more than 12,319 families in shelter by FY14, an additional 10.2% increase.

But why? Beginning here, the unexpected impact of rapid re-housing policies comes into focus.

Note: The figure for FY13 is an average of three months of data available in DHS Daily Reports.

Sources: New York City Department of Homeless Services, Critical Activities Report: Family Services, 2002–09; New York City Department of Homeless Services, Critical Activities Report: Adult Families Services, 2010–11; New York City Department of Homeless Services, Critical Activities Report: Families with Children Services, 2010–11; New York City Department of Homeless Services, Daily Report, October 4, 2012.

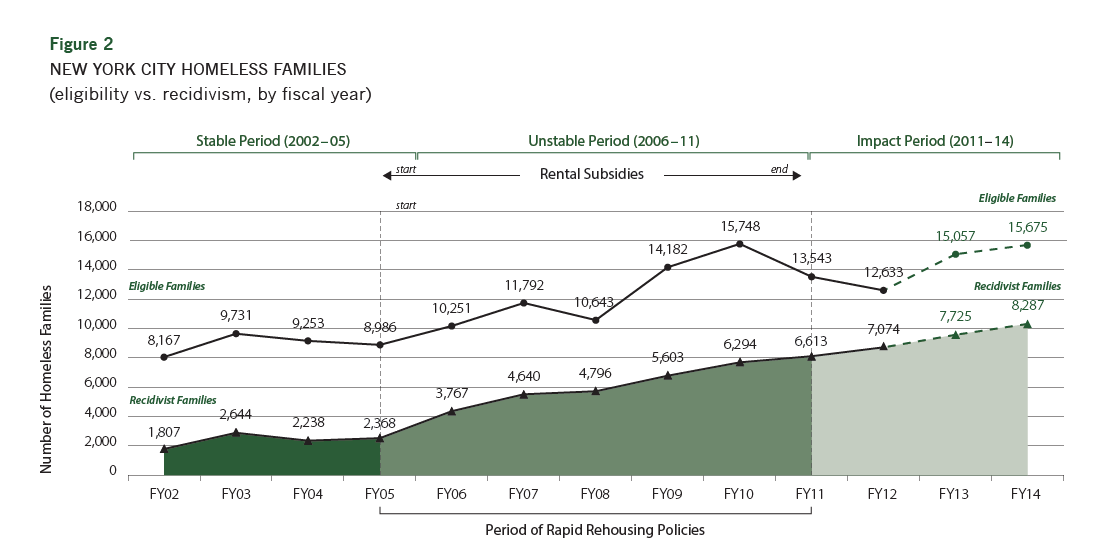

Shelter Eligibility and Recidivism

As the average shelter census in New York City was increasing, so too was the rate at which families were undergoing the eligibility-determination process necessary to qualify for shelter. Between FY05 and FY10 the number of eligible families increased 75%, putting more pressure on an already strained shelter system (see Figure 2). This increase revealed a need for shelter that was already present—one that became visible as rapid r-ehousing initiatives drew more families into the system.

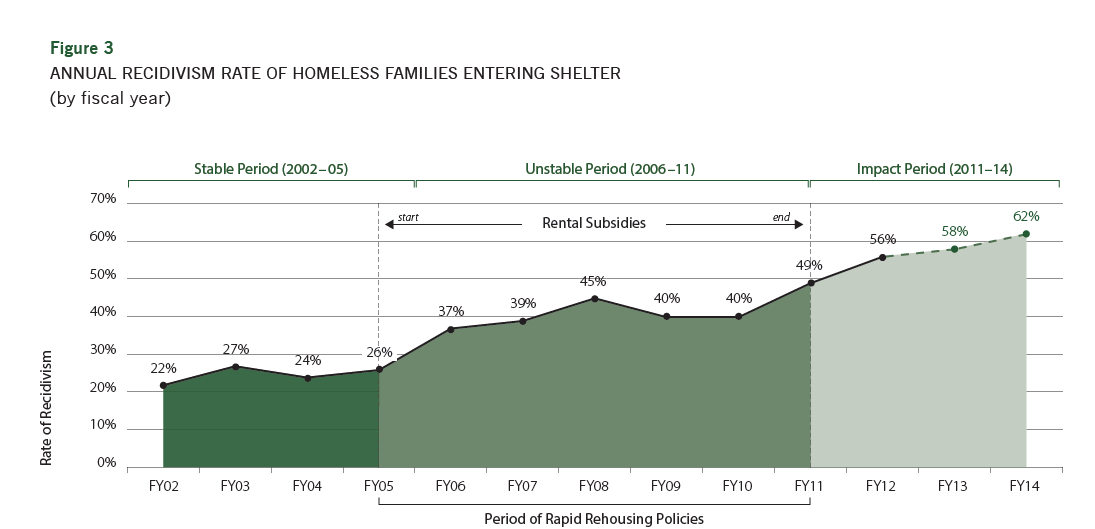

In addition, the recidivism rate, or the rate at which re-housed families return to shelter, saw an upward trend.(5) Prior to FY05 and the implementation of rapid re-housing initiatives (see Figure 2, “Stable Period,” FY02–05), recidivism in the city’s shelter system remained relatively stable, at a little over 20%. Beginning with rapid re-housing rental subsidies in FY05, this equilibrium was upset and the system thrown out of balance, resulting in a quick rise in family recidivism (see Figure 2, “Unstable Period,” FY06–11). Even taking into account other factors that contribute to family homelessness, including the economy and housing costs, this rate of recidivism indicates that families are being moved into housing before they are ready to maintain it.

Note: The drop in eligibility for FY08 is the short-term result of a shift from one rental-subsidy initiative (Housing Stability Plus) to another (Work Advantage). Selected figures reflect revisions made in a following year’s Critical Activities Report. Data for eligibility and recidivism in FY12 are calculations based, respectively, on the eight months of data available in Local Law 37 Reports and the 56% recidivism rate published by the Coalition for the Homeless in the blog post “Record Shelter Numbers Explained in One Graph,” June 29, 2012.

Sources: New York City Department of Homeless Services, Critical Activities Report: Family Services, 2002–09; New York City Department of Homeless Services, Critical Activities Report: Adult Families Services, 2010–11; New York City Department of Homeless Services, Critical Activities Report: Families with Children Services, 2010–11; New York City Department of Homeless Services, Local Law 37 Report, July 2011–June 2012.

By FY11, when rapid re-housing rental subsidies were halted, the number of recidivist families had risen an unprecedented 179%, with little sign that it was leveling off. Today, the city’s recidivism rate stands at 56% (see Figure 3).(6) Moreover, a longitudinal analysis of recidivism through the “stable” and “unstable” periods of rapid re-housing initiatives projects recidivism rates of 58% and 62% for FY13 and FY14, respectively (see Figure 3, “Impact Period,” FY11–14).

Note: The short-term declines in the recidivism rates for FY09 and FY10 are attributed to the introduction of a new rental subsidy (Work Advantage). Figures for FY 2002–11 are calculated by dividing the number of “repeat families” reported in the Critical Activities Report by the number of “eligible families.” The figure for FY12 is taken from the Coalition for the Homeless blog post “Record Shelter Numbers Explained in One Graph,” June 29, 2012.

Sources: New York City Department of Homeless Services, Critical Activities Report: Family Services, 2002–09; New York City Department of Homeless Services, Critical Activities Report: Adult Families Services, 2010–11; New York City Department of Homeless Services, Critical Activities Report: Families with Children Services, 2010–11; New York City Department of Homeless Services, Local Law 37 Report, July 2011– June 2012.

During the six years when rapid re-housing policies dominated the city’s strategy for reducing family homelessness, the demand for shelter (whether measured through a daily census or the number of families applying for eligibility) and recidivism rates both increased significantly. These trends are not projected to reverse themselves anytime soon. But that’s not all.

Length of Stay in Shelter

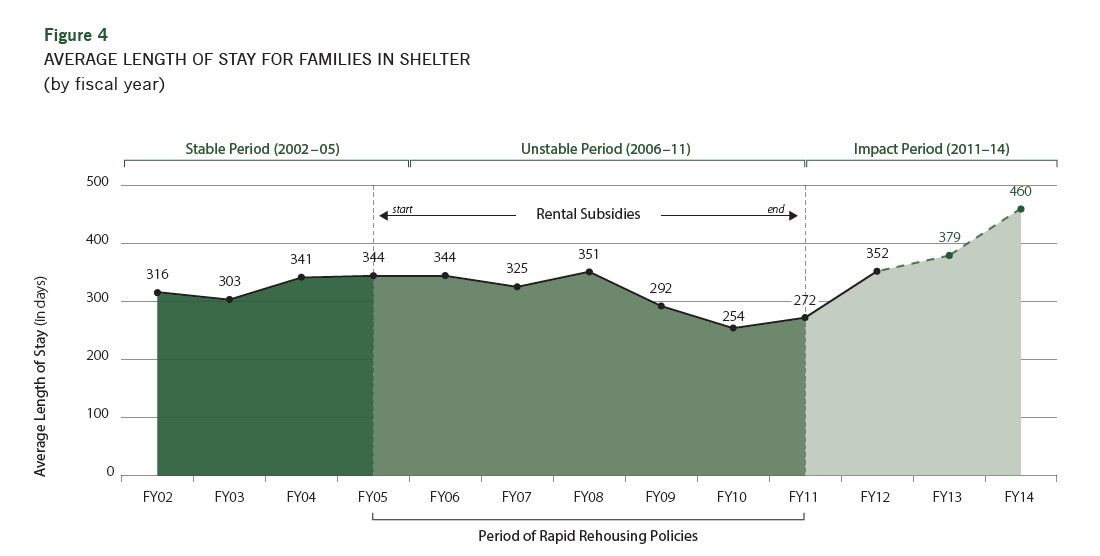

Along with the increases in shelter census, eligibility rates, and recidivism rates, rapid re-housing also greatly affected the length of time families stayed in shelter. In FY12, the year after rapid re-housing was discontinued, the average length of stay (LOS) in shelter rose 29%, to 352 days. In other words, family-shelter stays were lasting 50 weeks, almost an entire year (see Figure 4, “Unstable Period,” FY06–11).(7) Projections based on recent trends indicate a 31% increase in LOS by FY14, for an unprecedented 460 days, or 15 months. Once again, rapid re-housing not only increased shelter demand, eligibility, and recidivism, but also length of stay, thereby leading to increased costs. But how much?

Note: The significant drops in LOS for FY09 and FY10 were the direct result of intensive rapid re-housing placements during this period. However, the trend reversed in FY11. Figures for FY10 and FY11 are an average of the lengths of stay for adult families and families with children weighted to reflect the proportional size of each group. The figure for FY12 is an average of the nine months of data available in Local Law 37 Reports.

Sources: New York City Department of Homeless Services, Critical Activities Report: Family Services, 2002–09; New York City Department of Homeless Services, Critical Activities Report: Adult Families Services, 2010–11; New York City Department of Homeless Services, Critical Activities Report: Families with Children Services, 2010–11; Coalition for the Homeless, “Record Shelter Numbers Explained in One Graph,” June 29, 2012.

Cost of Shelter

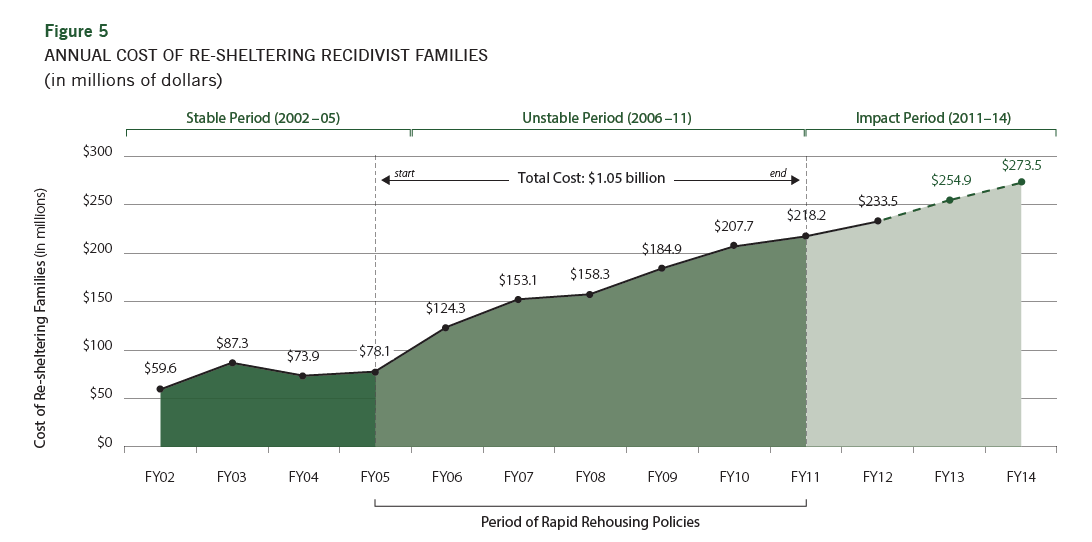

New York City’s adherence to rapid re-housing policies not only destabilized the shelter system and homeless families; it did so at an unanticipated cost.(8) Prior to the shift to rapid re-housing, the average cost of shelter recidivism was approximately $74.7 million annually. Between FY05 and FY11, when rapid re-housing was in full swing, the total cost of returns to shelter was an astonishing $1 billion, an average of $174.4 million per year (see Figure 5). This drastic spike in the cost of re-sheltering families who enter the system multiple times represents a 179% increase over the amount spent prior to the implementation of rapid re-housing policies.

Moreover, the cost of shelter attributed to recidivism continues to rise. It totaled $233.5 million for FY12 and is pro- jected to reach $254.9 million and $273.5 million in FY13 and FY14, respectively. As a consequence, the average estimated annual cost for the current “Impact Period” (FY11–14) is $253.9 million, 46% higher than during the rapid re-housing period (FY05–11; see Figure 5). This constitutes a true reversal of fortunes for the city.

Note: All figures represent the number of “repeat” families multiplied by $33,000, the annual cost of sheltering a family.

Source: New York City Department of Homeless Services, Critical Activities Report: Family Services, 2002–09; New York City Department of Homeless Services, Critical Activities Report: Adult Families Services, 2010–11; New York City Department of Homeless Services, Critical Activities Report: Families with Children Services, 2010–11.

The Impact

The purpose of this report is not to issue an indictment of New York City; the city government’s task of controlling and reducing family homelessness is a daunting one. Instead, the goal has been to take a critical look at the long-term impact of federally driven rapid re-housing policies, using New York City as a case study. Ultimately, the rapid re-housing initiatives of the last decade have, for numerous families, failed to deliver the intended long-term housing stability. In fact, by all accounts examined here, they have failed more than half of these families. This failure raises fundamental questions as to the future effectiveness of this type of policy, widely seen as the key to reducing family homelessness across the country. Rapid re-housing may appear to work in smaller metropolitan and rural localities (only time will tell regarding its continued success), but it clearly has created problems over the long run in a large-scale setting.

As this report demonstrates in the case of New York City, rapid re-housing was analogous to a temporary steroid injected into a stable system, destabilizing city shelters by creating an unnecessary demand, identifying unmet needs through increased eligibility, almost tripling the rate of family recidivism, increasing the average length of shelter stay, and driving up shelter costs. All of this, in turn, created new emergency needs for additional shelter space. Since the end of rapid re-housing in New York City, in May 2012, six new family shelters have opened, with three more in the pipeline for early 2013.(9) In fact, New York City was just forced to authorize an additional $43 million for family shelters.(10) In essence, rapid re-housing left New York with a costly hangover in the form of an overwhelmed family-shelter system.

The lesson to be drawn from all of this should be clear: “one size fits all” policies for addressing family homelessness do not work.(11) Not all families are equal. Some families successfully transitioned to permanent housing after their shelter stays, but others did not. Many have multiple needs beyond simple housing that should be addressed before their move to independent living.(12) Rapid re-housing was a failed experiment that produced unwanted incentives and unwarranted costs, all of which the city’s Department of Homeless Services must now address. In New York City, rapid re-housing became a short-term fix for a long-term problem. Whether or not it is successful in the future in other parts of the country, for now the caution light is on.

Resources

(1) Coalition for the Homeless, “Basic Facts About Homelessness,” (accessed December 14, 2012) ■ (2) From 2005 to 2011 the Department of Homeless Services (DHS) implemented two initiatives that promised to move families rapidly from shelter to permanent housing: Housing Stability Plus (HSP) and Work Advantage. HSP, introduced in 2005, offered a five-year housing subsidy to homeless families and individuals. It was replaced in 2007 with Work Advantage, which provided a subsidy with a strong link to employment and self-sufficiency; New York City Department of Homeless Services, “Housing Stability Plus, Background,” “Budget Cuts To ‘Advantage’ Program Leave New York City Homeless in the Lurch,” Huffington Post, March 20, 2011, (accessed December 13, 2012) ■ (3) New York City Department of Homeless Services, “DHS Critical Activities Report, 2005-2011,” (accessed December 5, 2012) ■ (4) New York City Department of Homeless Services, Critical Activities Report: Family Services, 2002– 09; New York City Department of Homeless Services, Critical Activities Report: Adult Families Services, 2010–11; New York City Department of Homeless Services, Critical Activities Report: Families with Children Services, 2010–11; New York City Department of Homeless Services, Daily Report, October 4, 2012 ■ (5) For the purpose of this report, families are identified as “recidivist” if they have entered the shelter system more than once. ■ (6) New York City Department of Homeless Services, Critical Activities Report: Family Services, 2002– 09; New York City Department of Homeless Services, Critical Activities Report: Adult Families Services, 2010–11; New York City Department of Homeless Services, Critical Activities Report: Families with Children Services, 2010–11; New York City Department of Homeless Services, Local Law 37 Report, July 2011–June 2012 ■ (7) New York City Department of Homeless Services, Critical Activities Report: Family Services, 2002– 09; New York City Department of Homeless Services, Critical Activities Report: Adult Families Services, 2010–11; New York City Department of Homeless Services, Critical Activities Report: Families with Children Services, 2010–11; Coalition for the Homeless, “Record Shelter Numbers Explained in One Graph,” June 29, 2012 ■ (8) New York City Department of Homeless Services, Critical Activities Report: Family Services, 2002– 09; New York City Department of Homeless Services, Critical Activities Report: Adult Families Services, 2010–11; New York City Department of Homeless Services, Critical Activities Report: Families with Children Services, 2010–11 ■ (9) Michael Howard Saul, “City to Expand Shelters Amid Jump in Homeless,” Wall Street Journal, September 25, 2012 ■ (10) Doug Turetsky, Homeless for the Holidays, and Beyond, IBO Web Log, posted January 7, 2013 ■ (11) An in-depth examination of this issue, with policy recommendations for utilizing a three-tiered system to address families’ individual needs, is clearly laid out in A New Path: An Immediate Plan to Reduce Family Homelessness, published by the Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness, February 2012. ■ (12) See Institute for Children and Poverty, Job Readiness: Crossing the Threshold from Welfare to Work, March 1994, reissued April 1999; Institute for Children and Poverty, An American Family Myth: Every Child at Risk, January 1995; Institute for Children and Poverty, A Tale of Two Nations: The Creation of American “Poverty Nomads,” January 1996; Institute for Children and Poverty, The Age of Confusion: Why So Many Teens Are Getting Pregnant, Turning to Welfare and Ending Up Homeless, April 1996; Institute for Children and Poverty, A Welfare Reform–Homelessness – Foster Care Connection?, September 1999; Institute for Children and Poverty, Children Having Children: Teen Pregnancy and Homelessness in New York City, April 2003; Institute for Children and Poverty, The Cost of Good Intentions: Gentrification and Homelessness in Upper Manhattan, March 2006; Institute for Children and Poverty, A Shelter Is Not a Home … Or Is It?, Revisited, 2010; Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness, Profiles of Risk: Education, July 2011; Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness, Housing Assistance Underfunded but Critical for Survivors of Domestic Violence, October 2011; Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness, Profiles of Risk: Maternal Health and Well-being, February 2012; Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness, Intergenerational Disparities Experienced by Homeless Black Families, March 2012; Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness, One Degree of Separation: Education, Sex, and Family Planning among New York City’s Mothers, October 2012; Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness, Little Room to Play: How Changes to City Childcare Policies Reduce Opportunities for Working Families, July 2012.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

The National Perspective—

The Struggles of Homeless Hispanic Families

by Matt Adams and Anna Simonsen-Meehan

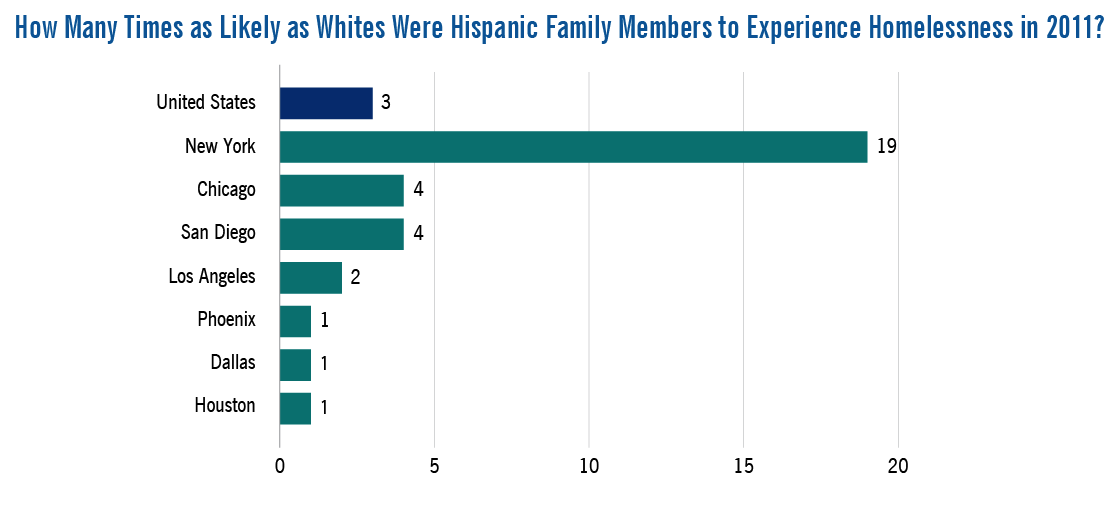

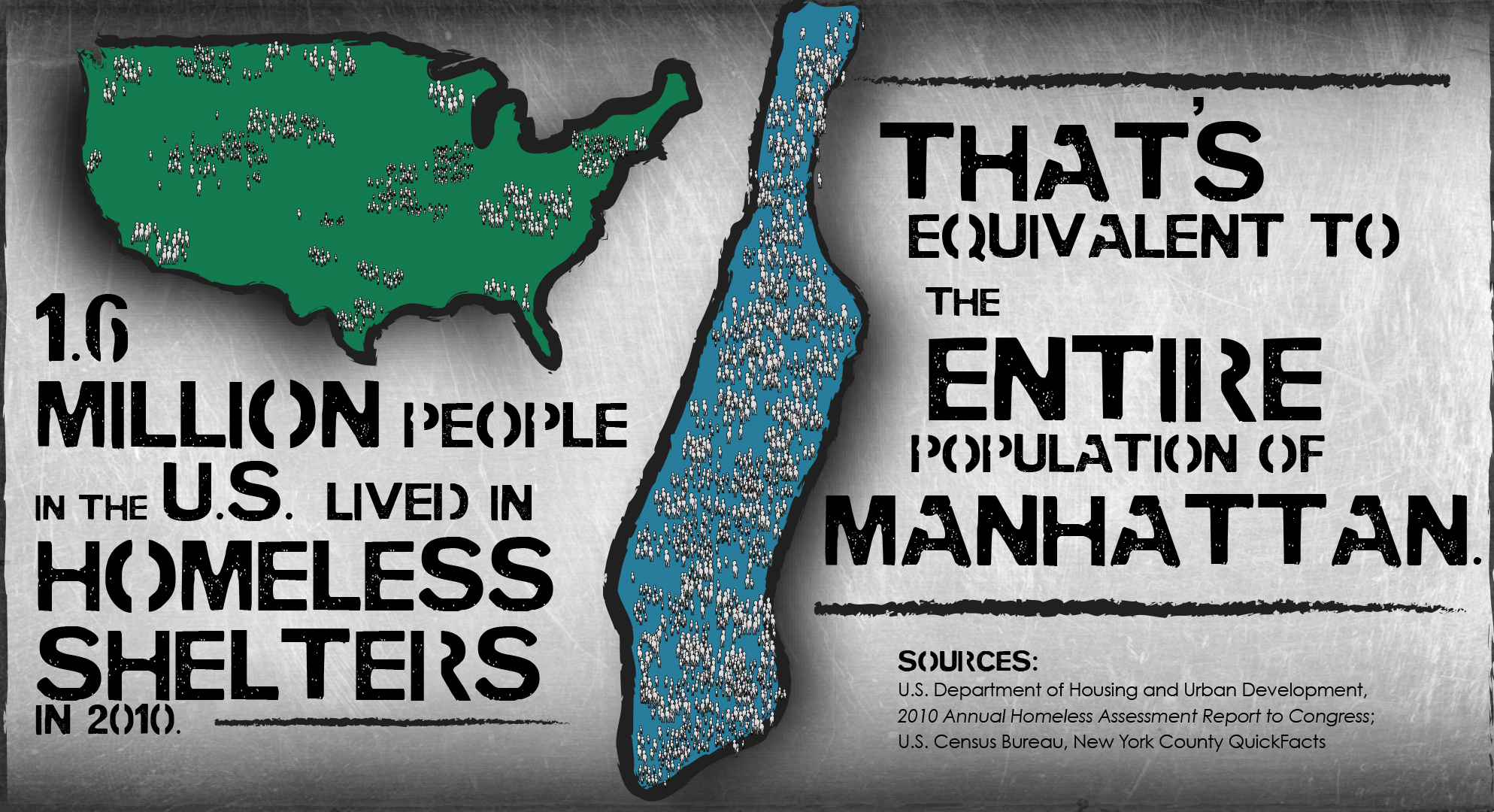

Studies over the years have continually shown that Hispanic families are overrepresented in U.S. homelessness and poverty statistics when compared with whites. In 2011 over one-quarter (29.6%) of Hispanic families with children lived in poverty, more than twice the rate of white families (12.2%). Hispanic families also experience homelessness at much higher rates. One of every 396 Hispanic family members stayed in a homeless shelter in 2011, a rate nearly three times higher than that for persons in white families (one in 1,067; see Figure 1).

Note: A value of one indicates equal likelihood between Hispanics and whites.

Source: U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, The 2011 Annual Homeless Assessment Report to Congress; U.S. Census Bureau, 2011 American Community Survey 1-year Estimates.

Such statistics may represent an undercount of Hispanics who are homeless due to factors affecting many families of Hispanic origin. Language barriers, fear of deportation of undocumented family members, and migratory labor patterns result in less use of homeless services and, as a consequence, underrepresentation in homelessness statistics. Hispanic families may rely on help from relatives over agency-run social services, reducing the rate of literally homeless Hispanics but increasing the number of doubled-up families who live in potentially overcrowded and substandard conditions and are disconnected from services. These arrangements may also limit access to employment and other opportunities, since living with relatives can reduce the time a person spends with co-workers, friends, and others outside the extended family. Some studies suggest that literally homeless Hispanics are also more likely to stay in atypical unsheltered locations, for example in abandoned buildings, thus frequently “hidden” from and overlooked by homelessness surveyors.

Issues surrounding immigration status limit low-income Hispanic families’ access to benefit programs that could keep them from experiencing homelessness. Welfare-reform legislation passed in 1996 resulted in much lower public benefit participation rates among legal non-citizen households; even qualified immigrant families living in poverty are prevented from receiving aid by complex application rules, confusion over eligibility criteria, limited English skills among applicants, and fear that participation may disqualify family members from obtaining permanent residency status (“green cards”). In “mixed-status” households, fear of deportation keeps undocumented parents from applying for assistance for their qualifying U.S.-born children. Harsh legislative measures taken in recent years by states seeking to address unlawful immigration have heightened deportation concerns among Hispanics and have further deterred eligible low-income immigrants from seeking assistance. These laws also place organizations at risk of prosecution for aiding illegal immigrant households in need of social and homeless services.

Several factors place many Hispanic families and individuals in a financially unstable position. Nearly two-fifths (38.0%) of Hispanics have less than a high school degree, a rate almost four times higher than for whites (9.6%). In 2011 a Hispanic full-time employee with a bachelor’s degree or higher earned one-sixth (16.5%) less in weekly full-time salary ($1,000) than a white worker ($1,165) with the same level of education. In 2009 Hispanic households had approximately one-eighteenth of the accumulated wealth that whites possessed ($6,325, compared with $113,149), leaving them with less to fall back on in times of economic hardship. This amount decreased by two-thirds (65.5%) between 2005 and 2009, due primarily to the housing-market crash, which strongly affected states with large Hispanic populations. (The wealth of white households saw a 15.6% decline during the same time period.)

Differences exist within the broad “Hispanic” category, which disguise factors that can increase vulnerability to homelessness—situations linked to national origin, generational status (such as being foreign-born versus being third-generation), immigration status, and level of English-language proficiency. For example, the poverty rate among foreign-born families originating in Mexico was 36.0% in 2011, as opposed to 16.4% for families born in South America. More than two-thirds (70.7%) of U.S. families born in Mexico have limited English-language skills, compared with less than half (45.9%) of South American–born families, making it even more difficult to achieve economic stability.

Like blacks and American Indian or Alaskan Natives, Hispanics face prejudice and other substantial access barriers to decent employment, education, and housing not experienced by whites. While the nature and expression of biases vary by racial and ethnic group, the effects are similar: lower educational attainment and earned income, considerable gaps in wealth accumulation, and higher rates of poverty and homelessness. At the same time, it is important to note that society is dynamic. Immigration reform under consideration by the 113th Congress may help reduce some barriers to accessing services by offering a path to citizenship for some undocumented immigrants already living in the United States.

Resources

U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, The 2011 Annual Homeless Assessment Report to Congress ■ U.S. Census Bureau, 2011 American Community Survey 1-year Estimates ■ Stephen Conroy and David Heer, “Hidden Hispanic Homelessness in Los Angeles: The ‘Latino Paradox’ Revisited,” Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences 25, no. 4 (2003): 530 – 8 ■ Susan González Baker, “Homelessness and the Latino Paradox,” in Homelessness in America, ed. Jim Baumohl (Westport, CT: The Oryx Press, 1996), 132 – 40 ■ Congressional Research Service, Noncitizen Eligibility for Federal Public Assistance: Policy Overview and Trends, August 2011 ■ Congressional Research Service, Unauthorized Aliens’ Access to Federal Benefits: Policy and Issues, September 2011 ■ Anna Pohl, et al., “Barriers to Accessing Services: The Importance of Advocates Accompanying Battered Immigrants Applying for Public Benefits,” in Breaking Barriers: A Complete Guide to Legal Rights and Resources for Battered Immigrants (2004) ■ National Alliance to End Homelessness, Changes in Laws Relating to Immigration: Impact on Homeless Assistance Providers, 1997 ■ Associated Press, “Push for Tough State Immigration Measures Could Spread if Supreme Court Upholds Arizona Law,” Washington Post, April 28, 2012 ■ Gretchen Keiser, “Catholic Conference Testifies Against Immigration Bill,” The Georgia Bulletin, March 3, 2011 ■ Pew Hispanic Center, Illegal Immigration Backlash Worries, Divides Latinos, October 2010 ■ U.S. Census Bureau, 2007–11 American Community Survey 5-year Estimates ■ U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Labor Force Characteristics by Race and Ethnicity, 2011 ■ Pew Research Center, Wealth Gaps Rise to Record Highs, 2011 ■ Pew Hispanic Center, Latino Children: A Majority Are U.S.-born Offspring of Immigrants, May 2009 ■ Pew Hispanic Center, A Portrait of Unauthorized Immigrants in the United States, April 2009 ■ Character Education Partnership, What Works in Character Education: A Research-driven Guide for Educators, February 2005 ■ Kristyn Harms and Susan Fritz, “Internalization of Character Traits by Those Who Teach Character Counts!,” Journal of Extension 39, no. 6 (2001) ■ U.S. Department of Education, WWC Topic Report: Character Education, June 2007 ■ Kafia Ayadi, “The Role of School in Reducing the Prevalence of Child Obesity,” Young Consumers: Insight and Ideas for Responsible Marketers 9, no. 3 (2008): 170 – 8 ■ Karin M. Ekström, “Parental Consumer Learning or ‘Keeping Up With the Children’,” Journal of Consumer Behavior 6 (2007): 203 –17 ■ Debbie Easterling, et al., “Environmental Consumerism: A Process of Children’s Socialization and Families’ Resocialization,” Psychology and Marketing 12, no. 6 (1995): 531– 50 ■ Border Security, Economic Opportunity, and Immigration Modernization Act, S 744, 113th Cong., 1st sess.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

On the Record—Conferring on Homelessness

Researchers at the Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness regularly attend conferences in order to keep abreast of developments in the field. Below, ICPH staff members offer UNCENSORED readers overviews and impressions of several local and national events that took place this year in different parts of the country. On February 21 and 22, 2013, in Seattle, Washington, the National Alliance to End Homelessness held its annual conference on family and youth homelessness. U.S. senator Patty Murray of Washington and Nan Stoops, executive director of the Washington State Coalition Against Domestic Violence, were among the keynote speakers. Sessions explored a range of issues, including the use of rapid re-housing as a model to solve family homelessness, strategies to end veteran homelessness, services for runaway and homeless youth, and the intersection of domestic violence and homelessness. Topics discussed during several sessions are highlighted below.

Health Care Reform: What’s in It for Families and Youth?

This session discussed the ways in which the Affordable Care Act (ACA) affects families and youth experiencing or at risk of homelessness. As part of the ACA, $1.5 billion—separate from Medicaid—was set aside for grants for Maternal, Infant, and Early Childhood Home Visiting Programs to help low-income at-risk populations; these programs have proven to be a cost-effective means of improving outcomes for mothers and their children.

Though homeless families and youth are particularly vulnerable, the parameters of home-visiting programs have often excluded them. An advocate at Heartland Health Outreach in Chicago discussed that organization’s efforts to broaden the programs. Among the suggestions were having more training for home visitors with regard to the barriers they face when working with homeless families; basing home visitors in homeless shelters; and identifying key leaders and experts able to prioritize the issue going forward.

A representative of the Annie E. Casey Foundation addressed another change enacted as part of the ACA: the expansion of Medicaid for youth aging out of foster care, who will now be covered to age 26. This population is often at great risk of becoming homeless and has high rates of acute and chronic medical, mental health, and developmental problems. Though the expansion of benefits does not, as yet, allow Medicaid coverage for this transient population to follow them if they leave the state in which they were most recently in foster care, it moves the nation toward giving these young people “medical homes,” or home bases for health care.

Emerging Research and Practices on Veterans and Their Families