Publisher’s Note

Dear Reader,

Since its inception, UNCENSORED has been home to informative articles, thought-provoking essays, and poignant photographs illustrating that family homelessness is far more complex than a housing problem. Our Spring 2015 issue further emphasizes the importance of programs and services that go beyond housing to support children and families experiencing poverty and homelessness.

“The Peace Within” examines the growing use of yoga as a supportive tool for at-risk and homeless populations, looking in-depth at inventive programs across the country such as Lineage Project, Street Yoga, and Sheltered Yoga. The challenges faced by homeless students as they continue their education at the college level are explored in “Building a Bridge,” along with the promising programs that are gaining traction to help them through this often-difficult transition. Our final feature takes us on a trip to the Midwest to profile the innovative programs of three different service providers: the resourceful culinary and janitorial training programs at Shelter House in Iowa City, the essential budget and life-skills training at Hillcrest in Kansas City, and the multiple child- and parent-focused programs emphasizing healthy childhood development offered by People Serving People in Minneapolis.

“Beyond the Mandate,” this issue’s National Perspective article, looks at the number of children under the age of three being served by McKinney-Vento subgrants, demonstrating the extraordinary efforts of homeless school liaisons across the country.

We encourage you to save the date for our fourth biennial conference, Beyond Housing 2016, which will take place January 13–15, 2016 in New York City. Visit our conference website at BeyondHousing.ICPH.org for more information on registration, speakers, and how to submit proposals for workshops and panels. We hope to see you there and to continue the important conversation about family poverty and homelessness.

Sincerely,

Ralph da Costa Nunez, PhD, Publisher

President and CEO, Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

The Peace Within:

Yoga and Meditation for At-Risk Youth

by Katie Linek

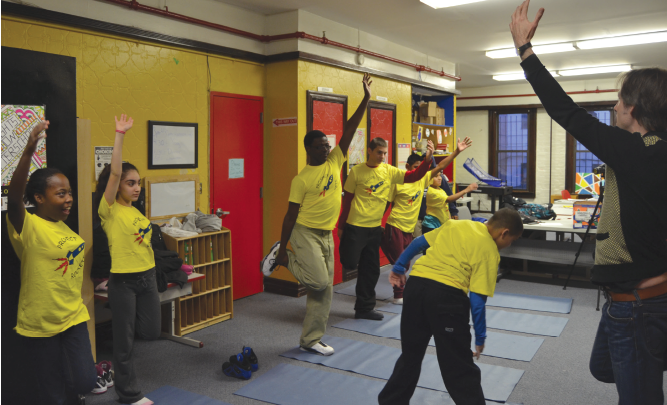

It is a Friday afternoon at an after-school program in the Bronx. A high-energy group of students, ages 12 to 17, talk and laugh excitedly amongst themselves. When Bart van Melik, an instructor for Lineage Project, calmly announces that yoga class is about to begin, he is barely audible among the cacophony of voices. Through the noise, however, the kids hear him and quickly sit on the yoga mats that line the room.

Lineage Project is a New York City–based not-for-profit that uses yoga, meditation, discussion, and other mindfulness techniques in working with at-risk youth to break the cycle of poverty, violence, and incarceration. The group’s mission is to teach alternative behavioral models that support young people in overcoming the enormous challenges of living in communities with very few resources. Today Lineage is being hosted at FutureLink, an after-school program held at the Prospect family shelter run by Homes for the Homeless, a social services provider based in New York. Some students enrolled in FutureLink come from the shelter, others from the surrounding community.

Concentration and focus are taught and demonstrated through the practice of yoga at the Prospect family shelter.

“Lineage Project is vital to our program,” explains Leo Benavides, education programs coordinator at Prospect. “The kids look forward to yoga and learn a lot of important skills, like how to breathe and concentrate.”

Previously considered an activity for New Age, spiritual types, yoga has risen to the cultural mainstream. The media and celebrities alike have touted its health benefits, leading to yoga’s now being practiced by more than 20 million people in the United States. People from all walks of life and all ages are now enjoying yoga.

Beyond the trendiness of yoga, however, lies its value as a therapeutic tool for numerous at-risk populations, from prison inmates to those suffering Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) to children experiencing homelessness.

According to America’s Youngest Outcasts, a report by the National Center on Family Homelessness (part of the American Institutes for Research Health and Social Development program), nearly 2.5 million children, or 1 child in 30, were homeless in America at some point in 2013. The impact of homelessness on children can be extremely detrimental and traumatic, with periods of prolonged stress leading to numerous cognitive and behavioral issues.

Yoga, a healthy practice for both the body and the mind, can help to counteract some of the stress associated with homelessness. It offers a gentle form of exercise that increases strength, flexibility, range of motion, and balance. In addition, stretching, controlled breathing, and meditation combine to help those who practice yoga relax. Several studies have found that regularly practicing yoga yields positive results with regard to stress reduction, mental health, increased behavioral, social, and cognitive skills, concentration, emotional regulation, and overall health—the very same areas in which children are negatively impacted by the experience of homelessness.

That is why programs like Lineage Project can be found in cities across the country, bringing the benefits of yoga to the children who need them most.

For example, Street Yoga, an organization that originated in Portland, Oregon, and is now headquartered in Seattle, Washington, has been using yoga since 2002 to help at-risk youth to “overcome trauma and to create meaningful, healthy lives.” Its goal is to help children and their families build skills like self-soothing, goal setting, and self-confidence that they can apply to their everyday lives.

Teens in the FutureLink after-school program learn balance and concentration and practice putting their best foot forward.

“Street Yoga shares yoga’s tools for healing and empowerment with youth experiencing homelessness, poverty, addiction, abuse and trauma,” says Stephanie Toby, co-executive director of Street Yoga. “We partner with sites already serving youth facing adversity, such as homeless shelters and treatment centers.”

Street Yoga holds weekly yoga and wellness classes for youth and their families at over 25 locations on the West Coast. Over 500 people have now been trained by the program to help youth overcome their struggles through yoga. In the more than 12 years since its founding, Street Yoga has served thousands of children and their families.

The main goal at Street Yoga is to provide classes that are predictable, safe, and fun. Toby explains, “Predictability allows youth to know what to expect from our classes, which creates trust and supports the re-regulation of their nervous systems. In other words, it’s easier for them to not immediately go into ‘fight or flight’ mode when faced with a stressor, or easier for them to transition from that mode to a calmer state. Safe classes allow all youth to feel successful and build resilience. Fun classes increase the likelihood that yoga will be an enjoyable experience and that youth will want to continue to participate.”

Another organization, Sheltered Yoga, located in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and Camden and Newark, New Jersey, provides instruction in yoga, meditation, and mindfulness in conjunction with strategies aimed at building wellness, self-esteem/self-worth, and tolerance as well as anti-bullying programming and curriculum. Sheltered Yoga serves people from homeless shelters, low-income schools, prisons, residences for those with disabilities, and addiction treatment facilities.

“One major aspect that we push in our curriculum in yoga and meditation is mindfulness of self. We help the kids recognize how important they are through self-esteem and self-worth mantras and mental exercises,” says Tina LeMar, executive director of Sheltered Yoga.

Mindfulness, or the focus of one’s attention on the emotions, thoughts, and sensations of the present moment, is a key component of yoga. An article in Social Work Today on the use of yoga and meditation for the treatment of anxiety explains that anxiety is regulated by the autonomic nervous system. Achieving mindfulness can actually calm the nervous system by focusing attention on the present moment and away from anxious thoughts and ruminations. Controlled breathing can also relax an overwhelmed nervous system, slowing the heart rate and putting the body into a parasympathetic state, or one of “rest and relaxation,” as opposed to the sympathetic, “fight or flight” state of a body under stress. Regularly practicing yoga can even train the nervous system to better handle stress as it comes.

According to van Melik, “Yoga teaches the children very skillful tools that they can use anytime. They learn how to relate differently to stress. Rather than pushing it away, they see what it’s like to be aware of it and notice how it comes and goes.”

Bart van Melik, an instructor with Lineage Project, guides students through a series of yoga poses while also incorporating themes such as positivity, trust, and compassion.

“A teenage girl in one of our classes wrote us a letter thanking us for bringing a ‘good medicine’ for her and the other students,” says Toby. “She said that life was very stressful and everything seemed to be moving very fast. She didn’t know how to handle everything that was happening. She said that yoga calmed her but also gave her more ‘power.’”

Experiencing stress is a normal part of development, but chronic stress, often faced by homeless children, can actually impair brain development—altering brain size, reducing cognitive skills, memory capacity, and emotional self-regulation, causing behavioral problems, and negatively affecting coping abilities and social relationships, explains America’s Youngest Outcasts. In addition, studies show that children who have experienced homelessness have greater difficulty in concentrating. Control over one’s attention, including the ability to focus, shift attention, self-regulate behavior, and ignore irrelevant stimuli, impacts both academic and social outcomes. Problems with attention have been linked to antisocial behavior and rejection by peers.

Amazingly, yoga and meditation can actually change the brain. A study published in the Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association found that meditation increases gray matter concentration in the brain, which is involved in learning, memory, the regulation of emotions, self-referential processing, and the ability to maintain perspective in a given situation. Practicing yoga can actually improve cognitive functioning, boosting focus and working memory. In a University of Illinois study, participants performed significantly better on brain functioning tests after doing yoga than after vigorous aerobic exercise.

“We now have scientific evidence that mindful practices can rewire the brain,” explains Toby. “These practices reduce suffering, such as symptoms of depression, anxiety, and PTSD.”

“It’s like I tapped into some part of my mind that I didn’t know I had. That’s what I like about yoga. That’s what yoga does for me,” explains Tyrik, one of the teens participating in the Lineage Project yoga class at FutureLink.

Yoga gives the kids tools to help them focus, gain insight, and have more control over their impulses. Yoga techniques have been shown through research to enable young people to stop and take a breath before they expose themselves to risky situations.

Not only do homeless children experience chronic stress, but youth who have experienced traumatic situations often overreact to stress. In an interview with Integral Yoga Magazine, Dr. Bessel van der Kolk, one of the world’s leading authorities on PTSD, explains that yoga offers a way to reprogram these automatic physical responses that are triggered by intense emotion. Neuroimaging studies of people in highly emotional states revealed that emotions such as anger, fear, or sadness cause reduced activity in parts of the brain related to feeling fully present. Therefore, learning to be present may hold the key to regulating emotions and controlling one’s response to stress.

Lineage Project is teaching the FutureLink class to do just that. The children sit with their eyes closed as van Melik guides them through meditation, inviting them to be aware of what is happening in their minds and to be mindful of thoughts instead of getting lost in them. “Remember that everything is constantly changing. When we’re okay with that, we feel a sense of freedom. When we no longer hold onto things, we feel free,” van Melik tells the children.

Problems with aggression and emotional regulation are common among children experiencing homelessness. According to Profiles of Risk: School Readiness, a report by the Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness (ICPH), children who experience homelessness at a young age are more likely to demonstrate behavioral problems such as aggression, social withdrawal, depression, and anxiety, which can in turn affect academic, social, and economic outcomes.

“A lot of kids come here with stress and the yoga helps them to relax,” explains Benavides. “One child in particular had anger problems and yoga provided him with a safe environment where he could relax, reset, meditate, and find a better outlet for his anger.”

Van Melik continues, “The kids have learned how beneficial it can be to pause, especially when kids are about to fight. We talk a lot about how to defend yourself in a skillful way, without using violence. They learn to pause in the moment when they are about to, out of habit, lash out.”

Beth Navon, executive director of Lineage Project, adds, “Yoga gives the kids tools to help them focus, gain insight, and have more control over their impulses. Yoga techniques have been shown through research to enable young people to stop and take a breath before they expose themselves to risky situations.”

“I learned that violence is not acceptable behavior. If you’re feeling stressed, just pull out a mat and do yoga,” says Jazmine, a young girl participating in yoga at FutureLink. “When I come home to my mom, she asks why I’m so calm and I tell her it’s because I did yoga today. She thinks I should do yoga every day.”

Lineage Project classes foster three primary skills: self-awareness, which is non-judgmental awareness of the body and mind; self-knowledge, which is the ability to recognize what creates stress and what relieves it, to see the repercussions of negative emotions and behaviors, and to understand the benefits of positive emotions and behaviors; and compassion for oneself and others, including cultivating and expressing kindness and empathy. Students who have participated in Lineage Project classes report an increased capacity for these skills, a sense of calmness and relaxation, and the ability to bring those feelings into other aspects of their lives—helping them to sleep better, prepare for sports, avoid fights, and show more patience toward themselves and others. Additionally, they report feeling less helpless, more able to calm themselves, and more trusting of others.

Lineage Project classes teach self-esteem, tolerance, and mindfulness.

Contributing to this success are the discussions that begin each Lineage Project class. Instructors present questions about universal themes such as compassion, gratitude, trust, and judgment, and the children are invited to contemplate those concepts while listening to and learning from one another’s answers.

“The discussion teaches the kids that they are not alone in this human experience,” explains van Melik. “When we were talking about self-judgment, one little boy said, ‘I never knew other people judged themselves too. I thought I was the only one.’”

Tyrik admits, “Yoga helps me to reflect on myself and makes me a better person.” Benavides agrees. “The meditation and discussion helps the kids learn a lot about themselves.”

The theme of today’s FutureLink class is lying. About ten students take turns telling stories of times they lied and why they did so. Van Melik asks them a series of questions prompting them to think further about the impact of lying on themselves and others. “When do you think lying is okay? How do you usually feel after you lie?” The class then considers the theme as it relates to the body; the kids are invited to move and to be conscious of how the body feels. Van Melik explains to the kids, “This is the truth of your experience. We’ve been talking about lying, but the body never lies to you. If you want to find the truth you can always find it in your own body.”

Those who practice and master yoga movements and poses can develop a positive relationship with their bodies, boosting their feelings of empowerment and control over the body and building self-esteem. Van Melik tells the story of one young girl: “She announced in front of all of her peers that yoga had helped her to stop hating her body.”

Many are aware that yoga is a healthy form of exercise, but the physical benefits of yoga extend far beyond a toned body. Yoga has been shown to improve cardiac functioning, lower blood pressure, increase lung capacity, reduce chronic pain, steady blood sugar levels in people with diabetes, strengthen bones, lower the risk of heart disease, strengthen the immune system, and help maintain a healthy weight.

Most importantly, though, practicing yoga helps to provide a sense of order in what may otherwise be a chaotic life. At the end of yoga class at FutureLink, the cacophony has completely quieted. Students calmly open their eyes, stretch, and share how they are feeling.

“The biggest lesson I try to transmit is that it’s possible to find peace within,” says van Melik. “It’s there, but we have to look for it.”

Resources

Lineage Project http://www.lineageproject.org New York, NY ■ Homes for the Homeless http://www.hfhnyc.org New York, NY ■ American Institutes for Research, National Center on Family Homelessness http://www.familyhomelessness.org Waltham, MA ■ Street Yoga http://streetyoga.org Seattle, WA ■ Sheltered Yoga http://shelteredyoga.org Columbus, NJ ■ Social Work Today Magazine http://www.socialworktoday.com Spring City, PA ■ Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association, Falls Church, VA ■ University of Illinois https://www.uillinois.edu Urbana, IL ■ Integral Yoga Magazine http://integralyogamagazine.org Buckingham, VA ■ Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness, New York, NY.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

Focus on the Midwest:

Shelters Designed for Lasting Success

by Suzan Sherman

More than a century ago, immigrants fled the squalor of East Coast urban centers in droves to put down roots in the Midwest, which in its relative emptiness provided the possibility for families to own homes and vast plots of land. The Children’s Aid Society’s “orphan train” program brought hundreds of thousands of homeless youth to the Midwest to be taken in by farm families, sparking a movement that lasted well into the 20th century. A new and better life in the Heartland was lovingly rendered in Laura Ingalls Wilder’s classic children’s book Little House on the Prairie, but this wholesome pioneer story is far removed from what the present-day Midwest looks like—particularly in its more industrialized cities. The collapse of the family farm, along with the rapidly shrinking manufacturing sector, has caused huge gulfs in regional employment options, and, not surprisingly, there’s been a concurrent rise in family homelessness. To get a better sense of what’s currently going on, UNCENSORED honed in on three small-, middle- and large-size cities in the Midwest—Iowa City, Kansas City, and Minneapolis, respectively—and the key agencies that serve families there, to learn more about the programs being utilized to get people back on their feet.

Preschool students learn about the date, day of the week, and weather in their morning lesson at People Serving People.

From Marginalization to Membership in Iowa City

Five years ago, Shelter House in Iowa City, Iowa, was just a small organization operating out of a single-family home, with a makeshift collection of cots, recliners, and bunk beds for serving up to 29 homeless individuals. Crissy Canganelli, who has been the organization’s executive director for 17 years, knew that if Shelter House was going to meet the needs of the growing homeless population without running her skeleton staff of 15 ragged, they had to make some changes—namely, immediately increase state and federal funding. The only homeless shelter in all of Iowa City, Shelter House has managed to do just that, and is now a 70-bed facility with a 40-person staff and a standing annual budget of $2 million. Despite its growth, the shelter consistently runs at capacity, with applicants often turned away or placed on waiting lists.

Shelter House offers an impressively diverse range of services to the men, women, and children who stay there, including 15-day emergency stays; 90-day stays for those taking part in STAR, a vocational-training program; and long-term housing for up to two years for homeless veterans, the vast majority of whom served in the Vietnam War. In addition to its 70-bed temporary facility, it also provides permanent supportive housing for up to 18 adults with serious and persistent mental illness at its Fairweather Lodge, with a preference given to veterans.

Left: Mike Rickettes, a line cook in the Culinary Training Program, prepares a fish dinner for both residents at Shelter House and families in need served by other local nonprofits. Right: Shelter House kitchen manager, Kimberly Blumer, helps prepare loaves of fresh bread for both shelter residents and clients of other local nonprofits serving individuals in need.

Genia, a former Shelter House client, had seriously questioned the possibilities for her future; caught in a cycle of poverty, she’d been living with a drug dealer. Yet she had the desire and courage to make changes through the support she received at Shelter House. Up until recently, Genia worked for Shelter House, serving as the organization’s administrative assistant, a position she held for a decade before leaving to work as a child care provider out of her home. Before coming to Iowa City, Genia lived in Chicago. “There was this commercial [on a billboard] that said, ‘Where will you be in the next five years?’” Genia recounts. “I had no idea where I would be in the next five years—let alone if I would be dead or alive. … That’s just crazy in and of itself. But whatever she [Genia’s Shelter House case worker] saw in me, I’m just glad she saw it, and I’m glad to be here and where I’m at today.”

Thomas first came to Shelter House with nothing but the clothes on his back. Of his time living on the street, he says, “It’s a horrendous feeling. Displaced, alone, where am I going to take a shower, how am I going to eat today? I came to the shelter the first day a little shaky, sick … and just with the realization that I didn’t want to do it anymore. If things were going to change, I needed to change my actions.” Thomas got involved with the Community Stories Writing Workshop, a Shelter House program affiliated with the renowned Nonfiction Writing Program at the University of Iowa (UI), and his book of poetry and prose, The Bullfrog Dreams of Flying, has since been published and can be found at the Iowa City Public Library.

Jerry Stevens, a Fresh Starts crew member, puts his new janitorial skills to work at Shelter House in Iowa City.

The Community Stories Writing Workshop is facilitated by Rossina Liu, who co-founded it five years ago and is currently writing her PhD dissertation on the program, a “kind of writing home” that has been built among its members. “Writing is self-discovery—it’s about uncovering new aspects of who we are in a narrative and revising how we see ourselves and our possibilities,” Liu says. The culmination of this yearlong program, which meets once a week, is the production of a journal printed in partnership with UI’s Center for the Book and a public reading at Prairie Lights, a local bookstore. As Liu writes in her dissertation, “In this space [the workshop], writing is transitional, a tool for crossing environments from the streets to the classroom, from marginalization to membership.”

For those interested in working in the food industry, Shelter House provides a 12-week Culinary Training Program, which offers skill building for employment in restaurants and industrial kitchens. While some meals prepared in the shelter’s kitchen are provided to Shelter House residents, a percentage are given to other area nonprofits and businesses for a fee as part of the Culinary Starts program, a resourceful revenue-producer for the organization. Another revenue builder is the Fresh Starts program, which provides low-cost janitorial services—performed by Fairweather Lodge residents—to seven local businesses.

Meg Jacobs, a long-standing Shelter House volunteer, shares story time with a child. Meg works with the resident children and guides them through a variety of fun and educational activities.

Among those who have taken part in Shelter House’s STAR (Support Training and Access to Resources) program—which works with residents to provide life-skills and vocational training, educational assistance, and child care services—75 percent have moved on to permanent housing. And yet, remaining economically stable and employable can be difficult. Iowa’s City’s current housing vacancy rate is 1 percent, with the national average typically 5–7 percent. “There’s no incentive for landlords to reduce rents, and our families are competing for housing with university students who are subsidized by their parents,” Canganelli says. Another obstacle to finding affordable housing, Canganelli notes, is “the current technology—which allows for quick and easy background checks—making it much more difficult for the people who come through Shelter House to move forward beyond their pasts.”

For those who live outside major urban centers and far from reliable transit systems, the added cost of a car, gas, and insurance can be crippling. And although Iowa City has an excellent public transportation system, it has the highest housing costs in the state. “The more affordable towns of Coralville and North Liberty do not have as good of a transit system, and with the rise of more service-sector jobs with weekend needs, when transit is not running as often, it’s tough for people to get around,” Canganelli says. These jobs, paying $8 to $9 per hour, often force households to double up with friends or relatives or work multiple jobs.

It’s a Hand Up, Not a Handout, in Kansas City

Chuck Arney, the COO and interim director of Hillcrest Transitional Housing, which has locations in seven counties in the Kansas City metro area of Kansas and Missouri, also finds the lack of public transportation to be a huge burden on the population he serves: homeless families, individuals, and youth. Fifty percent of Hillcrest’s programming, which Arney describes as “employment based,” is about the importance of saving money. With a rigor not unlike that of the 12-step Debtors Anonymous program, Hillcrest requires each resident to account for every penny spent and earned and to open a savings account, with the end goal being that those who graduate will have socked away $5,000 on average—enough to purchase a car.

Adults attending the Hillcrest 90-day program are required to find and maintain 35–40 hours of work per week and attend 4–5 weekly life-skills sessions, which are scheduled around their work and educational programs—an intense and rigorous schedule that keeps people focused on positive end results. An impressive 95 percent of Hillcrest graduates are self-supporting one year after completing the program, and 80 percent will have remained self-sufficient five years later.

A student at People Serving People works one-on-one with a volunteer tutor. The organization hosts 4,600 individuals who volunteer their time, skills, and services to families in need. (Photo courtesy of Jay Larson)

“Generational poverty is typical here—we’re seeing people in their 30’s and 40’s who have struggled their whole lives, using survivalist practices that are not good for self-sufficiency, or else a marriage has broken up and the mother can no longer afford housing,” Arney explains. Families and individuals generally arrive at Hillcrest after being referred by a caseworker at an emergency shelter or by a social worker at a local school. Arney’s staff have observed that “people are coming into the program underemployed with fewer and fewer benefits.”

Hillcrest’s youth program is comprised of teens ages 16–20. With 10 youth in residence at a time, the average stay at Hillcrest is one year. “First and foremost, we provide a safe, loving, and secure environment,” Arney explains, “and then stress the importance of continuing with their education”—be it a GED, high school diploma, college degree, or vocational training—as well as finding part-time employment. “Three recent graduates of the youth program,” Arney says with evident pride, “just moved on to college.”

Hillcrest offers rent- and utility-free housing with individual kitchens so that all residents learn to cook healthfully and on a budget rather than relying on fast food. In addition, Hillcrest’s community garden provides thousands of pounds of fresh produce and herbs to its residents free of cost, and is staffed by a network of volunteers who plant, tend, and harvest. Through community support, residents also receive items and services such as glasses, haircuts, work uniforms, dental work, and medical assistance.

A Shelter House volunteer helps a child with arts and crafts.

To be eligible for the Hillcrest program, a person must fill out an online application, with self-revealing questions such as, “Is there a warrant out for your arrest at present?” and “Have you been a battered person?” The person must also list all unpaid bills and other debts, but honest answers have never hindered Hillcrest’s intake staff from considering an application, as the only requirement to take part in the program is a willingness to work hard and make life changes.

An applicant is immediately placed on a waiting list, and to move to the top, he or she must call the Hillcrest office daily to check for openings—another way for intake staff to gauge an applicant’s tenacity and initiative. Upon the applicant’s acceptance into the program, a Hillcrest caseworker determines the primary cause of crisis—be it domestic violence, generational poverty, crime, divorce, or medical bills—a process Arney describes as “triage to find out where lives have been sabotaged.”

Back in the spring of 2014, James, a father of two, had been couch-surfing with friends and relatives and struggling to make ends meet as a janitor. A six-year custody battle had drained him of finances, and he owed several thousand dollars in back child support. James filled out an application for Hillcrest and had an appointment for an interview the following day, after which he was given 24 hours to consider whether or not he was up for taking part in the program. “I knew they were going to track every penny I had,” James says. “I knew there were rules that I had to follow—I had to be home by a certain time; I had to have inspections, and make sure that everything was clean.” But the rigor of the program, which also contained plenty of positive reinforcement, was just the right fit for James, whose motivation for succeeding was being able to see and care for his children and making sure he had his own place to spend time with them during his weekend visitations.

A young mother shares a bedtime story with her two girls. The family is staying at the residence operated by People Serving People in Minneapolis—the region’s largest and most comprehensive shelter provider. (Photo courtesy of Jay Larson).

James has since remarried and lives in a two-bedroom apartment five miles away from Hillcrest. “I still work at the same place I did before, but now I don’t have to worry if I’m going to have enough money to make rent, because now I budget. I’ve learned that I can purchase good, quality food at a grocery store rather than spending five times more in a restaurant. I’m not a millionaire, but I’m not worried if I’m going to have a roof over my head for my children.”

On his last night at Hillcrest, James wrote a letter to the resident who would be filling his room after he left. “If they took it to heart, or read it, I have no idea, but I tried to express that they had led themselves into something that could change their life if they wanted it to.”

Investing in the Youngest Homeless in Minneapolis

Not unlike its Midwest neighbors Kansas City and Iowa City, Minneapolis also finds itself challenged by a poor public transportation system and a lack of affordable housing. Despite being a progressive and wealthy city, it has the greatest educational achievement and income disparities between whites and people of color in the nation. Between 9 and 11 percent of children in Minnesota Public Schools are homeless or highly mobile, and in some schools, more than 95 percent receive free or reduced-price lunch.

Daniel Gumnit, the chief executive officer of People Serving People (PSP) in Minneapolis, the largest and most comprehensive shelter provider in Minnesota, hopes families can end their homelessness in one visit to PSP. What distinguishes his 99-room emergency shelter from many others is its plethora of on-site programs and services designed to address the specific barriers that homeless families face, with housing, employment, education, and emotional and life-enrichment needs all addressed.

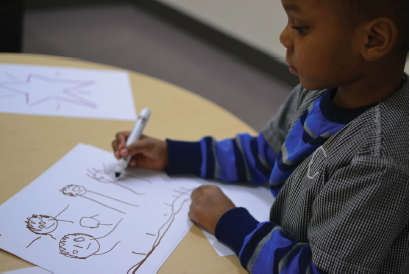

A boy living at Shelter House draws a picture of his family during a children’s art activity night.

The average stay at PSP is only 39 days, a negligible amount of time compared with New York City shelter stays, which average 400 days. Some families remain at PSP for just two to three days, though these families most likely experienced a one-time catastrophe such as a fire or health emergency, while other families, facing more deeply entrenched challenges, such as generational poverty, chemical dependence, or mental health issues, might remain at PSP for six to seven months.

Drew, Jill, and their two children found themselves homeless after suffering a job loss—at any given time, one parent hadn’t been working due to the high cost of child care—and falling behind on rent. They ended up at a local hotel before connecting with PSP. Says Drew, “When we got the phone call that we were accepted into the housing program, she [Jill] thought that it was a joke. She was like, ‘Are you serious?’ And then she started to cry. It was a dream come true. … I don’t think we could have gone through all those hardships without having a place like People Serving People to help us out.” Drew continues, “I mean, who knows, we could be under a bridge somewhere. I see people all the time that are just sleeping outside, and that’s scary when you have two children.” Since their stay at People Serving People, he and his wife have found steady employment, working together in a local café.

“Hennepin County has a ‘shelter-all’ mandate, which does not allow homeless families to remain out on the street,” says Gumnit. “Here in Minneapolis we have a profound and unique level of cooperation between state, city, and local nonprofits working together to end homelessness.” This level of cooperation and care extends far beyond those working in civil service and the nonprofit sector. All of the programs PSP provides are funded by philanthropy—be it donations by corporations, private foundations, or individuals. Its powerhouse board of directors come from Regis Corporation, Xcel Energy, UBS Financial, Best Buy, and General Mills, among other well-known firms. In addition, PSP has a monumental number of volunteers—4,600—who come from all walks of life, from nursing students to investment bankers to retirees, and offer their services as meal servers, tutors, tech mentors, and readers.

One of many volunteer tutors at People Serving People works with a preschool student to decorate her Summer Learning Packet.

“There’s a tremendous reward that comes out of working here,” Gumnit says, with volunteer slots filling up months in advance. Because of the shelter’s proximity to large Fortune 500 company offices in downtown Minneapolis, professionals often pitch in before and after work, or during lunch. A team from U.S. Bank comes every Wednesday morning to serve breakfast, and Ameriprise Financial serves food to residents seven times per month. Second Harvest Heartland, which is part of Feeding America, a national network of food banks, provides 450,000 pounds of food annually. In addition, PSP’s truck picks up pallet loads of fresh fruit, vegetables, and meat from Cub Foods/SuperValu two or three times per week.

To Gumnit, the greatest “return on the investment” comes from providing services to the youngest and most vulnerable in the population. Therefore, PSP’s Early Childhood Development Program—a licensed weekday preschool serving infants, toddlers, and preschool-age children and offering a trauma-informed curriculum focused on executive functioning skills and social/emotional development—is high on his priority list. So is the Parent Engagement Program, which provides support for parenting, behavioral management, and healthy childhood development. “If children are not properly prepared for kindergarten, they’re probably not going to be reading at grade level by third grade. Statistically, these children are four times less likely to graduate from high school by age 19 than a child who is reading-proficient in third grade. If you add in the factor of poverty, the student is 13 times less likely to graduate on time,” says Gumnit.

A teacher leads her preschool classroom at People Serving People, guiding young learners through an enriching, trauma-informed curriculum.

Like Shelter House, PSP has a long-standing Culinary Arts Training Program to help former residents and others facing challenges achieve self-sufficiency. The program offers classroom and hands-on training in the areas of sanitation, food preparation, roasting, baking, sautéing, equipment, and soups. Upon completion of the rigorous 13-week program, each graduate is given a uniform, a cookbook, a set of industrial kitchen knives, and a certificate. One of the Culinary Arts program’s graduates, Faduma Hashi, a native of Somalia, opened up her own café, Starlight Café, in downtown Minneapolis.

After exiting PSP, some families participate in a pilot program with a home visiting advocate who will assist the families in areas essential to maintaining self-sufficiency, such as employment, child care, transportation, and health care. The progress of these families is carefully monitored so that no one falls through the cracks. That is part of achieving People Serving People’s ultimate goal, one shared by Iowa City’s Shelter House and Kansas City’s Hillcrest Transitional Housing: that families who come through its doors will never return, and that those whom the organizations have served will find permanent homes and the means to maintain them.

Resources

Shelter House, http://www.shelterhouseiowa.org Iowa City, IA ■ Hill-crest Transitional Housing, http://www.hillcresttransitionalhousing.org Kansas City, MO ■ People Serving People, http://peopleservingpeople.org Minneapolis, MN.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

Building a Bridge:

From Homelessness to Higher Education

by Lee Erica Elder

Transitioning from high school to college often marks many firsts—the first time away from home, the first time living on one’s own, and the first time making decisions independently on a constant basis. It is an intense, unique time in life, when a young person is surrounded by peers with similar goals, exposed rapidly to new experiences, and given often-unprecedented freedom to learn and explore. Entering this phase of life while homeless, or unstably housed, means that the ensuing challenges can quickly become barriers to progress.

Here, UNCENSORED looks at organizations and individuals around the country working to analyze, address, and alleviate these challenges, and talks to scholars who have overcome homelessness to pursue higher education.

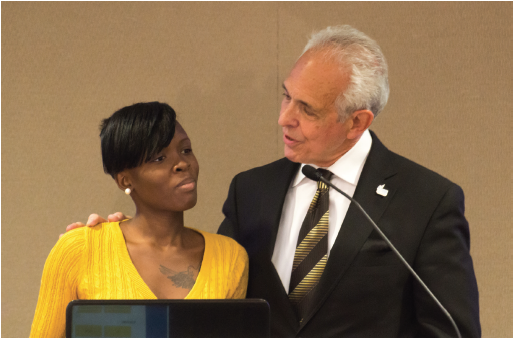

Joe Lagana, founder and CEO of Homeless Children’s Education Fund, joins Tierra Moses at the Bookends event in October 2014. Tierra spoke at the event, sharing her triumph over homelessness and other adversity.

Kat’s Story

Kat Allison, 21, is a junior at Lawrence University in Appleton, Wisconsin.

Her childhood was turbulent—she spent time in foster and group homes and was homeless, all before turning 18. “I struggled to finish high school,” she says. “Although I was highly energized and motivated to continue my education and pursue a college degree, the year after my 18th birthday was spent living on couches and relying on friends.”

Allison pays for her college education through full-time work and with the help of scholarships. “I have worked extremely hard to overcome the adversities of my recent past and work towards a successful future. I faced challenges in working and focusing on my studies while preoccupied with the looming issues accompanied by breaks and vacations. I’ve had very little housing stability—I once moved five times in an academic year. It’s very hard to find places to store my belongings, let alone move them, as I have everything I own with me.” She has received help with housing and financial aid thanks to Lawrence staff, but is concerned about those flying under the radar. “There is little known about the community of homeless students that exists within every larger community,” she says. “I am one of a handful of Lawrence students with a homeless status; however, there are thousands of homeless students within the greater Appleton community. I sincerely hope that more resources, especially scholarships, will become available in the near future.” Allison hopes to attend law school and funded her own study-abroad trip to Argentina, where she will be living until September of 2015.

Understanding Barriers to Higher Education

Allison’s experience illustrates why supportive services are critical. Many children who have experienced homelessness are determined to do well in high school and attend college, but lack of familial support increases the difficulty of accessing resources. The Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) and other official forms often require information that students do not have. “Imagine being a 17-year-old whose parents didn’t attend college, and you have to figure out FAFSA paperwork on your own,” says Carrie Pavlik, education services manager at Homeless Children’s Education Fund (HCEF) in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. “You might especially need these college loans because homelessness had a negative effect on your attendance and grades in high school, making it difficult for you to get an academic scholarship. You may not ask your guidance counselor for help in this area because you don’t want them to find out you are homeless.”

HCEF piloted a new scholarship last year, the Hope Through Learning Award. “We designed our award to help students overcome barriers to transitioning into post-secondary education, such as covering child care or transportation expenses,” says Laura Saulle, HCEF’s assistant executive director. “We’re also envisioning a support network that provides students with mentoring from peers and educational experts to help them transition to higher education.”

Nikkiya is all smiles as she celebrates her graduation from the Dorsey Schools/Penn Foster’s high school completion program. Nikkiya dropped out of school by age 12 but found the resources she needed to achieve lasting success.

For 16 years the National Center for Homeless Education has run the United States Department of Education’s technical assistance center for education for homeless children and youth. “Initially our work focused on K–12 education, specifically with the implementation of the McKinney-Vento Act, but there has been a natural evolution of the focus to homeless youth transitioning to and attending post-secondary education,” says Diana Bowman, the center’s director. “We work very closely with the National Association for the Education of Homeless Children and Youth (NAEHCY) on this issue, including developing a toolkit for supporting the needs of homeless youth in college.” The two groups collaborate on a helpline (1-855-446-2673), which launched in 2012. Cyekeia Lee, NAECHY’s director of higher education initiatives, has helped students find food, housing, and financial aid assistance through the helpline. Since its inception Lee has heard from more than 400 students, 75 percent of whom had already been admitted to or were attending college. “The higher education barriers and struggles start when they get there,” she says. “My goal is to build a bridge between the higher education world and the homeless education world. I help facilitate conversations about the definitions of homeless youth and outline the barriers they experience so these two systems can work together.” She also cites the importance of identifying a single point of contact on a college campus, a person who operates similarly to a McKinney-Vento liaison for a school district, identifying resources and advocating on students’ behalf. “They connect students to on-campus supports (housing, financial aid, academic advising, and counseling) and off-campus supports (food and clothing banks, shelters, transitional housing, and community mental health and social services),” says Lee.

Since 2011 the National Association of Student Financial Aid Administrators has collaborated with NAEHCY for the purpose of training financial aid administrators to work with homeless students. The group’s director of training initiatives, Jennifer Martin, chairs NAEHCY’s Higher Education Services Committee. “These students’ circumstances tend to exacerbate and amplify issues that other students may find easy to resolve. A relatively small issue, such as a $55 housing deposit, could be enough to keep a homeless student from enrolling in college,” says Martin.

Even if services are available, many students won’t identify as homeless for fear of stigma. “It’s not easy for students to disclose they are homeless,” says NAEHCY’s Lee. “That comes with many assumptions about them and their families. Identity is a challenge—a lot of colleges don’t want to admit that they have young homeless students on their campus, so many students don’t want to share their status.”

Tierra and TiAnn Moses share a prized moment with Pittsburg Steeler Troy Polamalu at the Homeless Children’s Education Fund’s Bookends event. Troy spoke to the audience about his Superbowl experience while Tierra shared her journey through homelessness at the “friendraiser” hosted by former Steeler Andy Russell.

Tierra’s Story

Tierra Moses is a 21-year-old certified medical assistant at Allegheny General Hospital in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Moses recently moved into an apartment of her own and plans to become a registered nurse. When she was a child, she and her family were often homeless, moving from shelter to shelter, and two of her older brothers were killed as a result of street violence. She graduated third in her class from both high school—with a 4.0 grade point average—and Pittsburgh Technical Institute, where she earned an associate degree. “I never let being homeless, moving around, not having a stable place, or living in a shelter—break me down,” she says. “I knew I wanted to go to college. I’ve been on the honor roll my whole life. I studied every day in college. It was a once in a lifetime experience.” In 2013 she was honored with the Homeless Children’s Education Fund Resiliency Award for her determination with regard to her education and future.

Programmatic Interventions Around the Country: Community-based Organizations and Educational Liaisons as a Bridge to Higher Education

When young people have to choose between helping their families—by working and seeking shelter—and going to school, community-based organizations and educational liaisons can step in to bridge the gap between homelessness and higher education. Such groups are integral components in making post-secondary education possible, mobilizing support to meet students’ basic needs and creating the space and freedom necessary to explore higher learning. “I have worked with quite a few students over the years who stopped coming to school because living was the priority,” says Shaun Rasmussen, educator and associate director of Something Positive, a New York City–based performing arts and education organization. “Trying to get into shelters, protecting themselves, or finding friends or relatives to stay with is their focus,” he says. “Some students engage in risky behavior—selling drugs, gang activity, prostitution—to secure a roof over their heads and a meal for a night.” Rasmussen, who has worked for a variety of community-based organizations, believes exposing students to options is half the battle. “It’s really important for students to know what’s possible.”

New York City–based Good Shepherd Services’ Young Adult Borough Center (YABC) programs offer alternative options focused on post-secondary planning, whether for college, vocational programs, or the workforce. These programs go beyond the classroom to provide resources and stability for students in transient housing situations. “In order to maximize their experience, they need to feel a sense of belonging,” says Pascale Larosiliere-Solon, program director of the YABC at Franklin K. Lane High School in New York City. “We often refer students to Good Shepherd’s Brooklyn LifeLink Program, which works as a bridge to assist students transitioning to college through academic and social support. Students participate in Life After High School workshops that familiarize them with resources offered on campus, and the role of their academic advisors. An additional resource is Good Shepherd Services’ mentoring program, where mentors work with young adults living in Good Shepherd group residences, supportive housing programs and foster boarding homes across New York City,” she says. Larosiliere-Solon, whose background is in social work, believes that working with students on time management is an important part of preparing them for college, given these students’ added responsibilities of maintaining housing and financial support. “Many people underestimate the mandatory appointments that students must attend in order to sustain themselves in housing and maintain good standing,” she says. “The process of going from one appointment to another, going to school, and maintaining a curfew (required in certain housing situations), can be undeniably overwhelming to the young person.”

Two colleagues join volunteers, students, and staff to honor the most recent high school and college graduates from Students Rising Above at the annual GRADWalk barbeque in San Francisco.

In Austin, Texas, Project Pathway is in its second year of service to 50 students transitioning to post-secondary education. “Students write and practice presentations, learn rules of etiquette and financial best practices, and acquire life skills,” says Cheryl Myers, education specialist at the Homeless Education Program at Education Service Center Region 13, which offers Project Pathway. “Through our education program and support from the Texas Homeless Education Office, we also offer assistance to the homeless liaisons from 17 school districts in our region. The liaisons invest in students—they take them on college tours, help with FAFSA awareness, plan college night at high schools, and help with credit recovery for graduation.”

Massachusetts’ Special Commission on Unaccompanied Homeless Youth estimates that there are 6,000 unaccompanied homeless youth in the state. YouthHarbors helps these students become stably housed and graduate from high school. The program began when homeless students at Malden High School, in Malden, Massachusetts, who were not affiliated with the channels through which interventions are often made—foster care or state and federal systems—needed services. “We had a group of students that were homeless that no one knew about,” says Executive Director Danielle Ferrier. “We opened our first site in October 2009, and essentially have added one each year. In our first year, 96 percent of the students in our program were housed at the end of the year, and the same percentage had either graduated or were on track to graduate.” Sixty percent of YouthHarbors’ population has an Individualized Education Plan (IEP). Developed with school staff and specialists, IEP’s outline special learning needs and mandate necessary educational assistance; staff work carefully with students on applications to make sure colleges are aware of their needs. Through their alumni program, YouthHarbors encourages students to remain engaged with the organization after graduation, helping them coordinate college housing and granting $50 checks for keeping in touch with staff on an annual basis.

San Francisco, California–based Students Rising Above serves 1,100 students, all low-income—61 percent live below the federal poverty line—through college prep workshops, mentoring, financial assistance, literacy programs, health care services, career guidance, and leadership development. One hundred percent of Students Rising Above’s high school graduates are accepted into four-year colleges or universities, and 98 percent enroll in those schools, from which 90 percent graduate within 4.5 years—eight times the national average for low-income, first-generation college students. “One student told us that he knew more people in his neighborhood who had been shot than who went to college,” says Lynne Martin, executive director. “Students are living without electricity, food, or running water—in garages, or in cars, or like one student, with 17 other people in a two-bedroom apartment. Many suffer from Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, but can’t afford counseling. They are living without functioning parents, or their parents died, or abandoned them. You can’t learn when you’re hungry or emotionally grieving.” Their Colleges2Career Hub—an online community for first-generation college students—serves 750 young people. Students Rising Above also assigns every student an advisor. “For many students, their advisor is the first consistent adult in their life, and this relationship extends well beyond college graduation,” she says.

Two attendees enjoy the annual GRADWalk event hosted by Students Rising Above. Every June, more than 300 students, volunteers, and staff gather in San Francisco for the annual barbeque, which honors the organization’s most recent high school and college graduates.

Nikkiya’s Story

By age 11, Nikkiya Gentry, of Detroit, Michigan, was living on the streets. She had dropped out of school by age 12. Eventually she was able to move in with a cousin and enrolled in Dorsey Schools/Penn Foster’s high school completion program. After receiving her high school diploma, she completed Dorsey’s culinary arts program. “I have something I can say is mine,” she says. “Without words, you are able to taste and feel what I achieved. I want to be able to build something, to leave a mark.”

Some students engage in risky behavior—selling drugs, gang activity, prostitution—to secure a roof over their heads and a meal for a night.

Risks Facing Homeless Students

Young adults experiencing homelessness are very likely to be food-insecure. These students may not meet a strict definition of homelessness, but their lack of resources still means they are in great danger. While there are not exact numbers detailing food insecurity among college students nationwide, a 2014 Oregon University study showed that more than half (59 percent) of all students surveyed were food-insecure sometime during the previous year. “They may have housing, but have to make decisions about buying food now vs. books for the semester,” says Jennifer Martin of the National Association of Student Financial Aid Administrators.

The Campus Awareness, Resource & Empowerment Center (C.A.R.E.) at Kennesaw State University in Kennesaw, Georgia, helps students who are homeless, housing-insecure, or food-insecure or who are or have been in foster care. Services include case management, food, clothing, and emergency shelter. “Our pantry through the C.A.R.E. Center offers food to any student who requests it,” says Kennesaw’s associate director for counseling and psychological services, Marcy Stidum, who is also the C.A.R.E. coordinator. “If they need additional provisions, we also offer linens and personal support items.”

Significant changes in a young adult’s life—such as transitioning from high school to college—can often trigger emotional and mental health issues. Ferrier, from YouthHarbors, believes that in addition to traditional mental and emotional health support, strong communities and networks are vital to stability. “I think that what is equally important and as therapeutic is a network, a community for homeless students,” she says. “When they get to college and are stably housed, but they still don’t have that person they call when they are not sure what to do—their risk is still really high. We reduce risk factors for trauma by focusing on communities and networks, so when they leave us, they have that person whose house they go to on a holiday, and the person they call in crisis.”

Continuing Education

There is still much to do to ensure that students are stably housed and able to pursue higher education. “Locally, we need campus awareness of homeless students and better ways to identify them and link them to services; statewide, more networks that include a coordinated approach between single points of contact and local school district homeless liaisons and youth service providers; and nationally, advocacy for laws and policies for strengthening supports and access to financial aid for homeless students,” says Bowman from the National Center for Homeless Education. “Awareness is key for understanding their unique needs. It’s important to remove the barriers they face so that they can continue in college and be successful academically.”

More than 125 students, volunteers, and staff gathered at the Orinda Country Club for the Students Rising Above Garden Party.

Interventions are integral to keeping students in college once they matriculate. “Our research tells us that the same challenges that prevent youth from graduating from high school can also spill over into their college years,” says Jonathan Zaff, executive director of Center for Promise, the research arm of America’s Promise Alliance—a partnership of national organizations dedicated to improving the lives of youth—in Washington, D.C. “We must remember that while getting economically and socially disadvantaged youth through the high school graduation door is an important milestone, we must be diligent in putting the resources and support in place that will help keep them moving to the next doors, of college, work, and life.”

Whether a student pursues a two- or four-year college or a vocational program, a successful transition into higher education establishes a sense of ownership and agency. Thanks to the many organizations and individuals dedicated to improving the lives of homeless students through both programming and policy, more young people are managing the challenges of housing insecurity and achieving their dreams of attending college. “These young people struggle to have the basics (food, water, shelter, and clothing) while trying to do their very best,” says NAEHCY’s Lee. “They need all the support they can get along the way. Some of them have indicated that there was a special teacher, mentor, counselor, or social worker that really pushed them because they could see their potential. Others may have already been affiliated with a college access program or bridge program that encouraged higher education access. I have had homeless students get accepted to prestigious private colleges, some [who] transition from community college to really great universities. Some have received their bachelor’s degrees and are going to graduate school. I have seen some students go from living in a car to getting their first apartment. They know that education is the key to getting them out of poverty.”

Resources

Homeless Children’s Education Fund, http://www.homelessfund.org Pittsburgh, PA ■ National Center for Homeless Education; Greensboro, NC ■ National Association for the Education of Homeless Children and Youth, http://www.naehcy.org Minneapolis, MN ■ National Association of Student Financial Aid Administrators, http://www.nasfaa.org Washington, DC ■ Something Positive, http://www.somethingpositiveinc.org New York, NY ■ Good Shepherd Services, https://www.goodshepherds.org New York, NY ■ Project Pathway Region 13 Education Service Center; Austin, TX ■ YouthHarbors; Waltham, MA ■ Students Rising Above, http://studentsrisingabove.org San Francisco, CA ■ Center for Promise, http://www.americaspromise.org Washington, DC ■ Dorsey Schools, http://www.dorsey.edu Madison Heights, MI ■ Oregon State University; Coravillis, OR ■ Campus Awareness, Resource & Empowerment Center; Kennesaw, GA.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

Conferring on Homelessness—

Beyond Housing: A National Conversation on Child Homelessness and Poverty—Are You In?

Every two years, hundreds of service providers, policymakers, and practitioners from across the United States come together in New York City for ICPH’s biennial conference, Beyond Housing: A National Conversation on Child Homelessness and Poverty. They discuss, learn about, and share innovative programs, solutions, and policies aimed at addressing this crisis. At ICPH’s 2014 conference, more than 450 people chose from among 40 interactive workshops and sessions, participated in in-depth discussions and networking opportunities, viewed the poignant images by photographer Craig Blankenhorn of children and families experiencing homelessness, and listened to three rousing keynote speeches.

ICPH president and CEO Ralph da Costa Nunez kicked off the conference with a keynote speech looking at the history of family poverty and homelessness, discussing the importance of the government safety net, and stating that the U.S. needs neither “big government” nor smaller government, but good government. According to Nunez, “Our job isn’t to get homeless people off the street. It’s to get homeless people on their feet.”

Author, educator, and MSNBC host Melissa Harris-Perry gave a humorous yet powerful lunch keynote, noting that race is “strongly determinative” when it comes to suffering from poverty and pointing to structural barriers to success for many minorities. Addressing those barriers, according to Harris-Perry, requires political will.

Nikki Johnson-Huston, who recalled her journey from childhood homelessness to a successful career as an attorney, delivered the final keynote. She compared her path with that of her brother, who had to enter foster care as a child and ultimately passed away at an early age. Johnson-Huston emphasized that her success was the result of both her grandmother’s efforts and the social safety net.

Sessions and workshops delved into themes including approaches to education, skill building, employment, research, policy, and advocacy. Other sessions looked at the work of successful programs, collaborations among organizations, and effective program strategies. Intelligent discussions were plentiful, new connections were made, and countless ideas were shared at the 2014 conference. With the 2016 conference less than one year away and registration now open, this is the time to make your plans to attend. Are you in?

You are also invited to submit proposals for sessions, workshops, and panels at BeyondHousing.ICPHusa.org. Conference sessions should provide new ideas and address topics and themes within the field of family homelessness, as well as offer opportunities to build bridges between professionals from various backgrounds. Participants are encouraged to make sessions interactive and explore the issues from innovative points of view.

Beyond Housing 2016 is sure to leave attendees refreshed and inspired to continue their work in the fight against child poverty and homelessness.

“My first but not my last!”

“Thank you for the quality of presenters and information.”

“I always look forward to the ICPH conference; it’s a great learning experience.”

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

The National Perspective—

Beyond the Mandate: Many States Report Serving Homeless Infants and Toddlers with McKinney-Vento Funds

by Matt Adams, Martha Larson, and Alyson Silkowski

In 2013, children under the age of six made up over half (51.2%) of all homeless children in families living in shelter, and one in ten (10.4%) were less than one year old. The McKinney-Vento Homeless Education Assistance Improvements Act (McKinney-Vento) provides critical protections for children old enough to attend school and authorizes funding to support their academic success. The law directs homeless school liaisons to ensure that young homeless children have access to available public preschool programs but does not specifically mandate services for children under three. Beginning with the 2011–12 school year, however, states were given the option to report the number of children ages 0–2 served with McKinney-Vento subgrants. Analysis of U.S. Department of Education data reveals that over half of states report serving infants and toddlers, indicating that many homeless school liaisons are reaching these young children, exceeding their programmatic requirements.

Compared with housed children, homeless children face a higher risk for poor health and developmental delays; gaps in socio-emotional and cognitive skills have been found to exist between homeless and housed low-income children as early as age three. Homeless infants and toddlers must be connected to health and educational services to overcome these gaps, and homeless school liaisons can support that process.

Local educational agencies (LEAs) may use McKinney-Vento funding to provide a range of services that can improve homeless children’s developmental outcomes, including early childhood education; referrals for medical, dental, and mental health care; and assistance with needs that arise due to domestic violence. LEAs that receive funding must report the number of students who are served through program dollars. Homeless children do not have to be enrolled in an LEA to be served; McKinney-Vento-funded referral services, for example, may support not only a homeless student in kindergarten but also a two-year-old sibling.

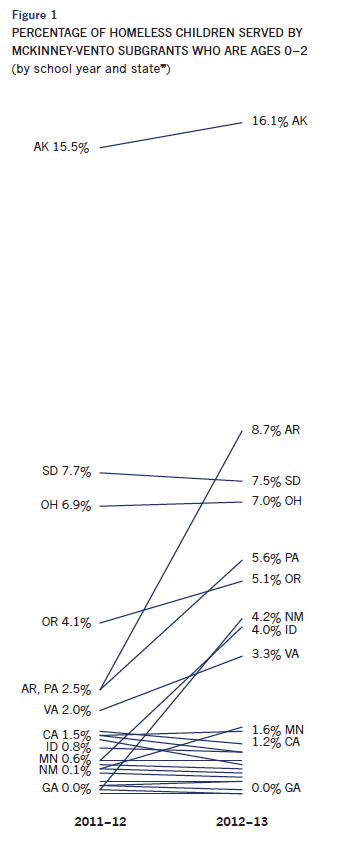

During the 2011–12 school year, 28 states reported serving a total of 10,591 children under the age of three, with California (4,903), Ohio (1,211), and Alaska (695) serving the greatest number. The following school year, 30 states and the District of Columbia reported serving 11,569 children ages 0–2. Among the 24 states that provided data both years, the percentage of children ages 0–2 served was generally low; in 14 states, children under three comprised 1.5% or less of all homeless children assisted through McKinney-Vento subgrants (Figure 1). However, Alaska, South Dakota, and Ohio served a high percentage (6.9% or more) of homeless children ages 0–2 both years. While the percentage of homeless children served who are ages 0–2 changed little in the majority of states, Arkansas, Pennsylvania, New Mexico, and Indiana reported much higher rates during the 2012–13 school year than in 2011–12.

*Only states that reported serving homeless children ages 0 –2 are displayed. Some states reported serving so few children that the results total 0.0% due to rounding. Note: Twelve states are not labeled on the graph due to spacing. For those states that are not labeled, data for the 2011–12 and 2012–13 school years, respectively, are: MD (1.4%, 1.5%), CO (1.4%, 1.0%), MT (1.3%, 0.7%), MI (1.1%, 1.0%), NY (0.8%, 0.8%), NV (0.7%, 0.6%), IL (0.6%, 0.5%), NE (0.5%, 0.4%), DE (0.3%, 0.3%), FL (0.2%, 0.3%), KY (0.2%, 0.1%), and KS (0.1%, 0.0%). Source: U.S. Department of Education, Consolidated State Performance Reports, School Year 2011–12; U.S. Department of Education, Consolidated State Performance Reports, School Year 2012–13.

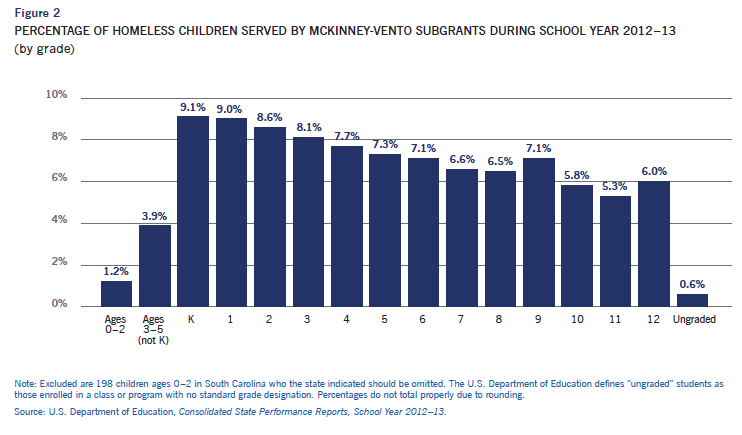

Nationwide, far fewer homeless children under three than school-aged homeless children are served with McKinney-Vento subgrants; at 1.2%, the percentage of homeless children ages 0–2 who were served during the 2012–13 school year was one-third that of children ages 3–5 (excluding five-year-old children in kindergarten [Figure 2]). Given that not every state reported data and that homeless school liaisons are required to assist homeless children only in preschool and above, the low rate of homeless infants and toddlers served is not surprising. Because providing the number of children ages 0–2 served is a new reporting option, more young homeless children are likely being served through McKinney-Vento than are documented.

The states that did not report serving any children ages 0–2 may be supporting these vulnerable children in other ways. As an example, Massachusetts did not report either year but prioritizes homeless children for child care subsidies and has used competitive grant funding from the U.S. Department of Education to improve collaboration between the state’s early education system and homeless service agencies. Additionally, young homeless children can be connected to services through other state and local entities. Head Start programs, for example, are directed to identify and prioritize homeless children for enrollment, and states receiving Individuals with Disabilities Education Act grants are required to locate and assess all homeless infants and toddlers with disabilities.

That a majority of states report serving children ages 0–2 with McKinney-Vento subgrants indicates that, despite limited resources, many homeless school liaisons are going above and beyond the program’s legislative and regulatory requirements to assist homeless infants and toddlers. If they are not already doing so, all homeless school liaisons should determine if the school-aged homeless children they identify have any young siblings and should consult early childhood and special education providers in the LEA to refer these children to programs such as Early Head Start and early intervention services. Cross-program and -agency collaboration can improve identification of homeless infants and toddlers, expedite the referral process, and ensure that gaps in services are filled.

The capacity of homeless school liaisons to serve homeless children under three, an especially vulnerable but difficult-to-identify group, gives more cause to increase investments in McKinney-Vento. Currently, less than one-quarter (22%) of LEAs receive subgrants; this lack of funding constrains homeless school liaisons’ ability to fulfill even the basic requirements of McKinney-Vento. The Obama administration requested a 10% increase in funding for subgrants in Fiscal Year 2016, which would raise the program’s annual appropriations from $65.0 million to $71.5 million. However, more funding is needed to reach all homeless students and to enable more homeless school liaisons to invest the time and resources necessary to make vital connections with their early childhood education colleagues.

Resources

U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, The 2013 Annual Homeless Assessment Report (AHAR) to Congress ■ Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness, Head Start and Housing (In)stability: Examining the School Readiness of Children Experiencing Homelessness, September 2013 ■ Title X, Part C, Sec. 723 of No Child Left Behind Act of 2001, Public Law 107–110, U.S. Code 20 (2001), § 6301 et seq. ■ National Center for Homeless Education, McKinney-Vento Law Into Practice Brief Series: Early Care and Education for Young Children Experiencing Homelessness, Fall 2013 ■ Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness, Meeting the Child Care Needs of Homeless Families: How Do States Stack Up?, July 2014 ■ U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Promising Practices for Children Experiencing Homelessness: A Look at Two States, July 2014 ■ National Center for Homeless Education, Best Practices in Homeless Education Brief Series: Early Care and Education for Young Children Experiencing Homelessness, November 2013 ■ Patricia Ann Popp, “When Two Laws Go Walking: IDEA and McKinney-Vento Serving Students with Disabilities Experiencing Homelessness” (conference presentation, NAEHCY Annual Conference, Kansas City, MO, October 25–28, 2014) ■ National Center for Homeless Education, Education for Homeless Children and Youth, Consolidated State Performance Report Data, September 2014 ■ U.S. Department of Education, Fiscal Year 2016 Budget Summary and Background Information.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

Databank

Resources

U.S. Conference of Mayors, http://www.usmayors.org Washington, DC.

To download a pdf of Databank, click here.

About UNCENSORED

Spring 2015, Vol. 6.1

FEATURES

The Peace Within: Yoga and Meditation for At-Risk Youth

Focus on the Midwest: Shelters Designed for Lasting Success

Building a Bridge: From Homelessness to Higher Education

EDITORIALS AND COLUMNS

Conferring on Homelessness—Beyond Housing: A National Conversation on Child Homelessness and Poverty

Databank

The National Perspective—Beyond the Mandate: Many States Report Serving Homeless Infants and Toddlers with McKinney-Vento Funds

Cover: FutureLink after-school students strike a pose during a class that fosters physical and mental well-being.

50 Cooper Square, New York, NY 10003

T 212.358.8086 F 212.358.8090

Publisher Ralph da Costa Nunez, PhD

Editors Linda Bazerjian, Joanne King

Assistant Editor Katie Linek

Art Director Alice Fisk MacKenzie

Editorial Staff Matt Adams, Martha Larson, Alyson Silkowski, Mary Kate Hannan

Contributors Clifford Thompson, Lee Erica Elder, Suzan Sherman

UNCENSORED would like to thank Students Rising Above; Nikkiya Gentry; Homeless Children’s Education Fund; East End Studios; People Serving People; Jay Larson; Shelter House; and Homes for the Homeless for providing photographs for use in this publication.

Letters to the Editor: We welcome letters, articles, press releases, ideas, and submissions. Please send them to info@ICPHusa.org. Visit our website to download or order publications and to sign up for our mailing list: www.ICPHusa.org.

UNCENSORED is published by the Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness (ICPH). ICPH is an independent, New York City-based public policy organization that works on the issues of poverty and family homelessness. Please visit our website for more information: www.ICPHusa.org. Copyright ©2015. All rights reserved. No portion or portions of this publication may be reprinted without the express permission of the Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness or its affiliates.

![]() ICPH_homeless

ICPH_homeless

![]() InstituteforChildrenandPoverty

InstituteforChildrenandPoverty

![]() icph_usa

icph_usa

![]() ICPHusa

ICPHusa