Publisher’s Note

Dear Reader,

UNCENSORED aims to convey the urgency of child and family homelessness and to shine a light on promising efforts to fight it. I think you will find that the feature stories in our Spring 2014 issue do just that.

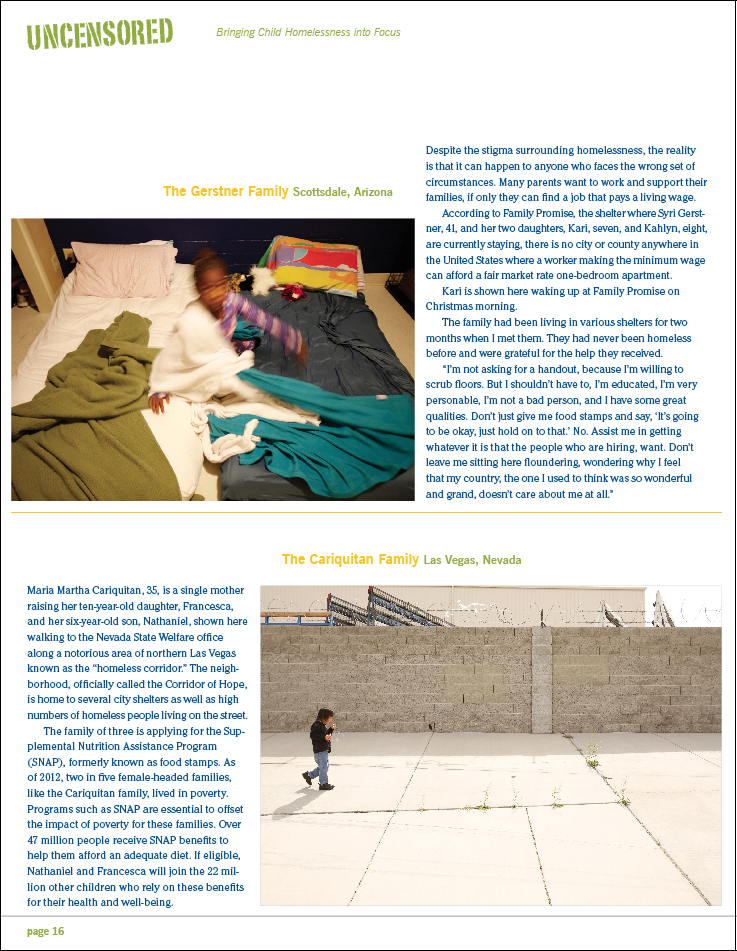

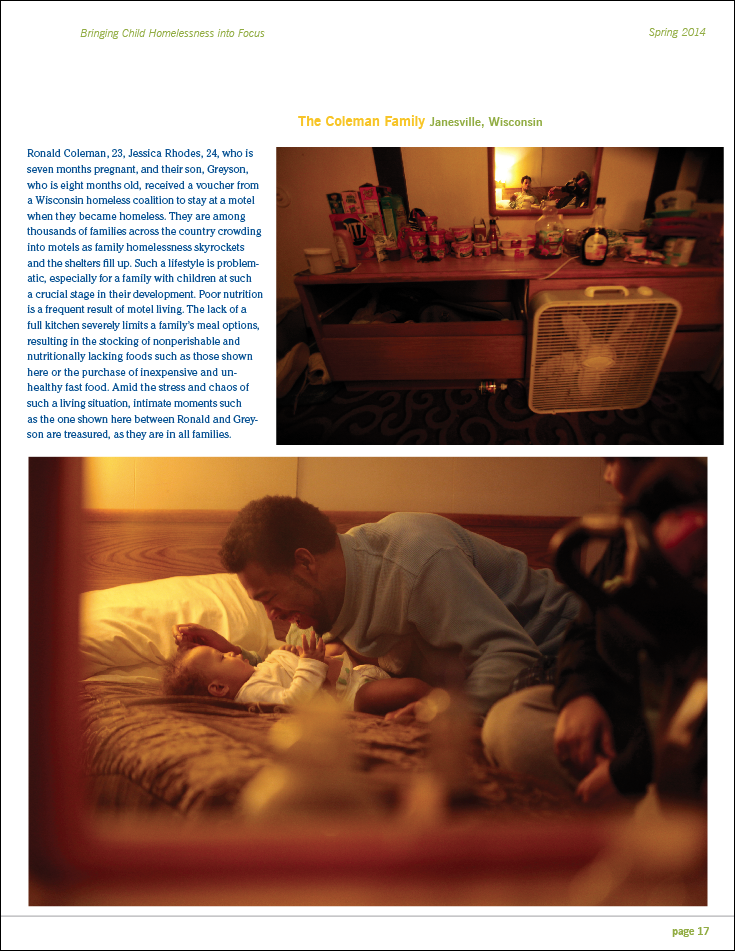

In “Bringing Child Homelessness into Focus,” the internationally renowned photographer Craig Blankenhorn shares the work he began two years ago, when he set out to document the heartbreaking experiences of families around the country with one thing in common: lack of a place to call home. Through their stories, we see the determination of these families—from the mother and father both studying to become medical technicians to the educated mother hoping for work even if it means scrubbing floors; in their faces, we see the pain and weariness of ordinary people facing the instability and uncertainty that are increasingly common in America.

But there are also increasingly innovative and promising ways of addressing the problem. And perhaps only in America would an aeronautical engineer and two ice-cream magnates come together to help impoverished individuals and families help themselves. That is the story told in “A Sweet Mission,” about the Yonkers, New York–based Greyston Foundation, with its open-hiring policy for the Greyston Bakery and its programs to employ, train, support, and encourage struggling adults who are trying to provide for their children.

These stories are just two components of our Spring issue, whose many perspectives on a growing problem offer a wealth of information, insights, and challenges.

Sincerely,

Ralph da Costa Nunez, PhD, Publisher

President and CEO, Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

A Sweet Mission:

The Greyston Foundation Bakes Brownies and Builds Lives

by Mari Rich

Dion Drew had plenty of time to think during a four-year prison sentence, which he received for selling drugs in his struggling neighborhood in Southwest Yonkers, New York. There, close to a third of all residents live below the poverty line and more than 40 percent of all adults lack high school diplomas. “I had been dealing since I was 14 and in and out of jail since I was 19,” Drew recalls. “So during that long four-year term I decided I was finally going to stay off of the streets and get a real job when I got out.” Drew knew that upon his release it would be difficult to find legitimate work because of his criminal record. Then he remembered hearing about the Greyston Bakery, a Yonkers-based facility with an unusual policy its management calls “open hiring.” An applicant need only walk in and put his or her name on a list; as soon as a post opens up, the applicant is hired—with no questions asked about work experience, criminal history, substance abuse problems, or past mental health issues.

Soon after leaving prison, Drew, now a youthful-looking 36, put his name on the list, and he was hired as a bakery apprentice two weeks later. He recently celebrated five years with the company and has been promoted several times. “You could say I’m in middle management now,” he says proudly. “I help with research and development, and I’m engaged in training new workers, many of them neighborhood people I used to hang around with.” He continues, “I think it’s ironic in a way that I once took so much from the community by selling drugs, but now I’m giving back to that same community in a very positive way.”

Asked if he might still be dealing drugs if he wasn’t working at the Greyston Bakery, Drew replies, “There is no question I would still be out there getting into trouble. This job has allowed me to take part in what I call a ‘real’ life. I get up every day and come to work, and I earn a living wage that lets me support my family.” The only sad part: after five years on the bakery floor, the naturally thin Drew doesn’t even smell the aroma of brownies anymore. “I take them home sometimes though,” he says, laughing. “The kids love them.”

The Greyston Bakery Story

Greyston’s motto is: “We don’t hire people to make brownies, we make brownies in order to hire people.” But hiring—and the visionary way the company goes about it—is only one of the objectives of the Greyston Foundation, the umbrella organization that oversees the bakery and several other programs. The motto could be: “We make brownies in order to hire people, offer high-quality day care for their children, help them find affordable housing, provide services for those living with HIV/AIDS, teach them to garden, and foster their personal growth in a holistic way.” While that might make for an excessively long motto, it only begins to describe the scope of the group’s mission.

How that ambitious mission began to be fulfilled involves a cast of characters that even the most creative Hollywood screenwriter might have difficulty imagining. Among them are a former aeronautical engineer turned Buddhist master, a pair of ice-cream magnates, and an award-winning architect.

Dion Drew, who once served prison time for selling drugs, has been promoted several times in his five-year career with the Greyston Bakery.

In 1982 Bernie Glassman, a Brooklyn, New York, native and former aeronautical space engineer who had given up that career for the serious study of Zen Buddhism, borrowed $300,000 and opened a small bakery in the New York City borough of the Bronx. He hoped that the bakery would provide jobs and income for members of the Zen Community of New York; that group, which he had founded a few years earlier, originally operated out of a run-down donated mansion in the Bronx called the Greyston Estate. (In preparation for the new venture, the aspiring bakers had traveled to the San Francisco Zen Center, whose members ran the popular Tassajara Bread Bakery, to learn about commercial food production.) Glassman, believing that employment was the first and most critical step in solving issues of homelessness and poverty, also recruited local homeless people to work in the bakery. The business was soon supplying a line of cakes and desserts to high-end retail outlets and restaurants—whose owners sometimes intimated to diners that the selections had been made by their own pastry chefs. While it might have been equally profitable to produce basic, less-upscale confections, Glassman was determined to prove that his employees could not only work at a skilled profession but excel at it. (He was particularly proud when Greyston’s cheesecake was named the best in the region by Zagat.)

Glassman later moved his base of operations to an abandoned 1920s-era lasagna factory in Southwest Yonkers. While some Yonkers residents were initially skeptical, thinking that the Buddhists would prove to be proselytizing nuisances, Glassman and his charges slowly won them over, donating food to local soup kitchens, engaging in community service, and—not incidentally—baking decadently delicious desserts.

“I think it’s ironic in a way that I once took so much from the community by selling drugs, but now I’m giving back to that same community in a very positive way.”

In 1987, at a meeting of the then-fledgling Social Venture Network, a group dedicated to connecting business leaders and social entrepreneurs who shared the goal of creating a just and sustainable economy, Glassman met Ben Cohen and Jerry Greenfield, the founders of the thriving ice-cream business Ben & Jerry’s. The pair were developing a new ice-cream sandwich and looking for a bakery to provide a thin, chewy brownie for it. Glassman agreed, realizing that a commercial account the size of Ben & Jerry’s would allow him to offer work to many economically disadvantaged job seekers.

The first shipment of brownies that arrived at Ben & Jerry’s Vermont headquarters in 1988, however, had become stuck together in unwieldy hunks. An attempt to excavate individual brownies from the 50-pound blocks only resulted in a crumbled mess. Frantically trying to salvage something from the shipment, workers stirred the crumbled pieces into batches of chocolate ice cream, serendipitously creating one of the most popular flavors in the history of Ben & Jerry’s—Chocolate Fudge Brownie.

Today, some 90 percent of the bakery’s brownies are used by Ben & Jerry’s as “mix-ins” for the Chocolate Fudge Brownie flavor and for Half Baked, a best-selling variety that combines chocolate and vanilla ice creams with brownies and bits of chocolate chip cookie dough. Additionally, the brownies can be purchased via the Greyston Web site, and the company recently partnered with Whole Foods to make the baked goods for that company’s Whole Planet line.

Open Hiring Requires Open Hearts and a Pragmatic Mind

The brownies—30,000 pounds a day of them—are produced by more than 80 people who, like Dion Drew, faced significant barriers to employment before coming to Greyston. Mike Brady, the president and CEO of the bakery, which brought in revenues of $10 million in 2012, explains, “No matter what mistakes someone has made in the past, everyone deserves a second chance. That’s the philosophy behind our open hiring.” He realizes that the work is not for everybody: for one thing, jobs in the bakery—which can require lifting enormous sacks of ingredients and withstanding excessively hot temperatures—are physically arduous. New hires are also sometimes unprepared for the demands of showing up for work on a regular basis and adhering to certain standards of workplace behavior. For that reason, all must undergo a rigorous training program, and their attendance, punctuality, and performance are monitored closely during six- to eight-month apprenticeships. “We are exceptionally serious about quality, safety, and cleanliness,” Brady asserts. “So, as you can imagine, we have very strict requirements for our bakery employees.”

Jessica Alicea, a Greyston child care worker known to her charges as “Miss Jessica,” is currently earning a college degree.

Some don’t come in for a second day of work, and others stop showing up after receiving their first paychecks. Brady takes that phenomenon in stride. “Of course, people like Dion, who remain with us for years, are enormous successes,” he says. “But in some respects, everyone who walks in our door and puts their name on our list is a success. They’re taking steps to change their lives and we’re happy to help them, whatever stage of readiness they’re at.” If an employee stays at the bakery for the entire apprenticeship period, he or she is eligible to join a union and to receive periodic raises as well as generous benefits. Some 35 percent of those hired successfully complete the apprenticeship process, and Greyston estimates that its open-hiring system saves Westchester County, where Yonkers is located, more than $1 million a year, thanks to reduced recidivism in the prison system.

The Greyston Foundation, which Glassman founded in 1992, operates with the support of public and private donors including the Detroit-based Kresge Foundation; New York’s Gary Saltz Foundation; the May and Samuel Rudin Family Foundation, also headquartered in New York; and the financial services giants Bank of America and Wells Fargo. The Greyston Foundation—which oversees the bakery as well as programs for both employees and nonemployees—also engages in workforce development, training aspirants for a variety of jobs in fields known to have consistent need for employees, such as medical billing, customer service, and building maintenance. Greyston then provides job-placement assistance. Since the workforce-development program was implemented, in 2009, it has helped more than 200 participants enter the work world.

Making a Path at Greyston

While Glassman knew that having a job is an important element of a meaningful, productive life, he also knew that it is just one element. As a result, Greyston has instituted a program called PathMaking, which involves assessing employees’ strengths and challenges to help identify specific issues, habits, and life experiences that aid or hinder positive movement along their individual paths. The PathMaking program helps employees set long- and short-term goals and encourages them to develop unity of body, heart, mind, spirit, and self.

While that may suggest New Age idealism, PathMaking is a decidedly real-world program with tangible results, providing guidance in continuing education, physical and mental health, nutrition, literacy, and personal finance, among other important areas. The Ruth Suzman PathMaking Center at the bakery, named in honor of one of its most devoted board members, features a library and several new computer workstations. “Our goal in PathMaking is to help people become more self-sufficient and self-assured, so they can become stronger participating members of the community,” Steven Brown, the president and CEO of the foundation, explains. “And—whatever you care to call it—that can only benefit the entire community.” An example of the program’s benefits is Celia, who has two young children and has worked at the bakery for nine years. Celia was embarrassed about not being able to read well and wanted to read to her children. Through the support of the PathMaking women’s group, Celia was paired with a volunteer reading specialist, who came to the bakery to meet with her for several months during her work shift (on company-paid time). Celia was able to register for classes to receive her Servsafe Certification at Westchester Community College the following year. She is one of four bakery employees currently enrolled in a bakery-sponsored PathMaking/Workforce Development GED pilot program.

The Other Stepping Stones

The remnants of a bagel and muffin breakfast buffet are spread out near the entrance to the Greyston Child Care Center, located just a few blocks from the bakery. “That’s left from the parents’ meeting we just had,” Jessica Alicea (or “Miss Jessica,” as her young charges call her) explains. “We don’t just provide day care and after-school programs. We have general meetings for parents where they can voice their concerns, parenting classes especially for fathers to encourage them to be a part of their children’s lives, sessions where everyone can get advice on child development … really, anything we can do to increase parent involvement, we’ll do.”

Alicea not only works at the center—which is free of charge to all bakery employees and provides affordable care to other Yonkers residents—she is the mother of two preschoolers who attend it and a seven-year-old who arrives in the afternoon for an after-school program. All three have been coming since infancy to the center, which is accredited by the National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC). “This is like a second home for them,” Alicea says, “and it’s that way for many of the children. I’ve been here since 2000, and I’ve gotten to see several of our students grow up. Some of them I met originally in the infant room are teenagers now!”

The center is licensed to accept 96 children, from ages six weeks to five years, and it provides a variety of programs, including art and music and movement. The vast majority of those who attend go on to pass the Creative Curriculum Assessment, which gauges their readiness for kindergarten.

“Knowing that their children are in good hands makes it much easier for parents to find and keep jobs,” says Alicea, who is earning a college degree in addition to working and raising her own brood. Greyston estimates that in 2012 alone, parents who were able to work because their children attended the child care center earned almost $800,000 collectively.

In addition to jobs and child care, the foundation is active in the movement for affordable housing and now has almost 300 units in its portfolio, including a new $32 million, multifamily development with 92 modern, energy-efficient apartments. Half of Greyston’s housing stock is reserved for the formerly homeless, who receive ongoing support services whenever needed. As of 2012, more than 200 formerly homeless tenants had been housed in Greyston units for longer than two years.

Preschool children participate in Reading Time at the Greyston Child Care Center.

The organization has also taken on the mission of serving and housing those living with HIV/AIDS at its bucolic Maitri Adult Day Health Center and Issan House complex, located on the site of a former convent overlooking the Hudson River in Yonkers. The Maitri program, which takes its name from the Sanskrit word for “loving kindness,” is the only adult HIV program of its type in Westchester County; its wide range of services (meals, counseling, and educational programming among them) has resulted in vastly better medical outcomes for attendees, including reduced viral loads and fewer infections. The apartment units in the Issan House are fully handicapped-accessible, and its residents have access to comprehensive medical treatment that encompasses both traditional and complementary therapies. Greyston estimates that having a health care facility directly onsite saves more than $100,000 a year through avoided emergency room visits for Issan residents, many of whom suffer from substance-abuse or mental health issues in addition to HIV/AIDS. There are also other, less tangible benefits. “Meditation at Maitri cleans my mind, counteracts the damage my meds do, gives me calmness in the midst of a storm,” says Lloyd. “I am calm because I know that Maitri has my back,” he adds. “The nurse answers all my questions and reminds me of questions I need to ask my doctor, and the Health Education and Nutrition groups teach me everything I need to know about my condition and my body.” Lloyd also attends the Coping With Loss group run by Brad Fritz and a clinical staff member every week. “It helps me to deal with the murder of my sister by her son,” he explains, “because it gives me a safe place to vent, a safe place to cry, and a place to cry out. I am comforted. Everything I learn at Maitri makes me stronger and more able to face the world outside.”

Can Brownies Be Green?

The bakery, which needed to expand because of steadily increasing demand for its goods, is now located in a 23,000square-foot facility—not far from the Yonkers waterfront—that was designed in 2000 by Maya Lin, the architect best-known for creating the Vietnam War Memorial in Washington, D.C. It was built on a former brownfield site contaminated by decades of industrial waste and pollution, which Greyston chose in large part because of the role the cleanup would play in revitalizing the entire area. The building, which officially opened in 2004, features several innovative energy-saving features, as well as a rooftop garden where employees can go to relax. Plans are underway to incorporate the vegetables that are grown there into employee lunches as a way to encourage good eating habits. Extending that mission to the general community, Greyston also runs an ambitious community-gardens project, which has resulted in the greening of several formerly empty lots.

Certifiably Beneficial

In February 2012 New York State began to authorize Benefit Corporations (sometimes referred to as “B-Corps”), entities that are required by law to create a “general public benefit,” which is defined as “a material positive impact on society and the environment.” That month Greyston Bakery became the first business in the state to register for the new designation.

“We don’t claim to be healing the entire world,” Mike Brady says, “but we do try to help every person who walks through our doors, and that seems like a very good start.”

Resources

Greyston Foundation; http://greyston.com/ Yonkers, NY ■ San Francisco Zen Center, San Francisco, CA ■ Social Venture Network, San Francisco, CA ■ Ben & Jerry’s, Burlington, VT ■ Kresge Foundation; http://kresge.org/ Detroit, MI ■ Westchester Community College, Valhalla, NY ■ National Association for the Education of Young Children; http://www.naeyc.org/ Washington, DC ■ Social Enterprise Alliance; https://www.se-alliance.org/ Minnetonka, MN ■ Delancey Street Foundation; http://www.delanceystreetfoundation.org/ San Francisco, CA ■ Gulf Coast Enterprises, Pensacola, FL ■ Homeboy Industries, Los Angeles, CA.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

To download a pdf of this photo essay, click here.

Bringing Child Homelessness into Focus:

A Photo Essay

by Craig Blankenhorn

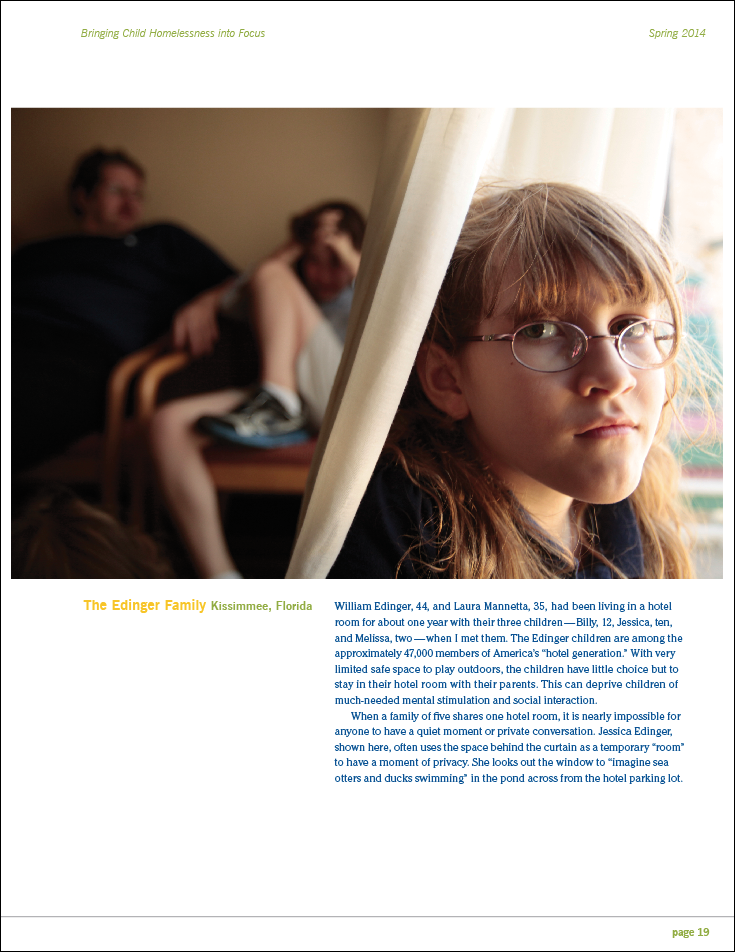

Internationally published photographer Craig Blankenhorn may be best known for his work photographing the stars of hit television shows such as Sex and the City and The Sopranos. Two years ago, however, Craig came across a very different subject—homeless children. It was then that he embarked on a personal journey to document the unseen and little-discussed phenomenon of family homelessness. Wanting to put a face to the devastating statistics he learned about the number of homeless children, and to shine a spotlight on this growing problem, Craig began spending his free time as a fly on the wall, chronicling the daily struggles of families trapped in the seemingly endless cycle of poverty and homelessness. Through this journey, Craig has learned about the experiences, determination, and struggles of homeless families. His aim is to chronicle, in every state across the country, the lives of families experiencing homelessness.

Craig continues his documentation of the crisis of child and family homelessness in America. The following photo essay is an expansion of a blog post featured on the Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness Web site, in which Craig shares his insights on the issues faced by homeless families. To learn more about his project, visit his Web site at www.ChildHomeless.org.

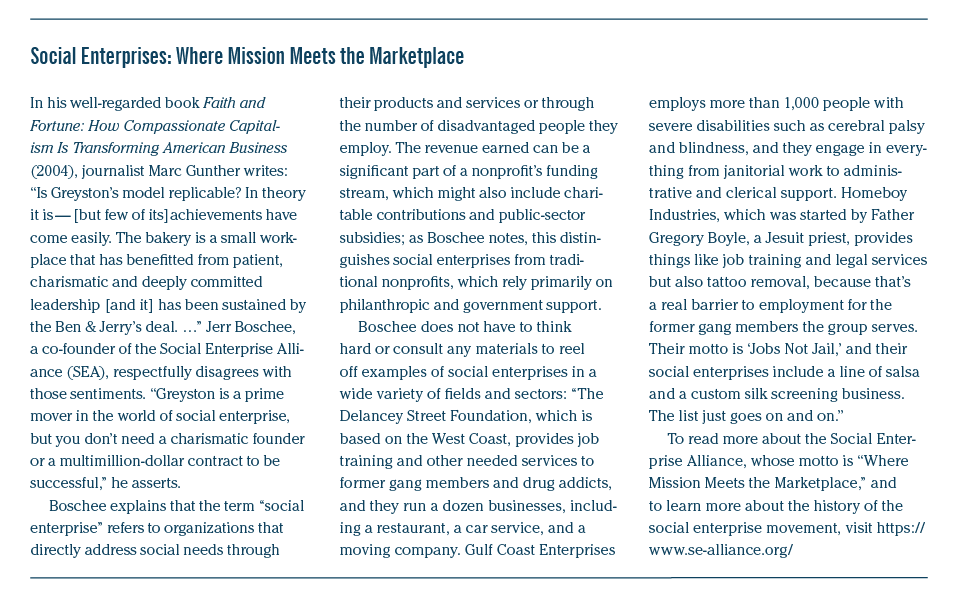

The tables are turned when photographer Craig Blankenhorn—shown here documenting the lives of a Las Vegas family experiencing homelessness—becomes the subject of a photograph. Blankenhorn follows consenting homeless families through typical days, snapping photographs that highlight the struggles they face, as part of a project that aims to draw attention to the plight of child homelessness. Photo courtesy of Las Vegas Sun News.

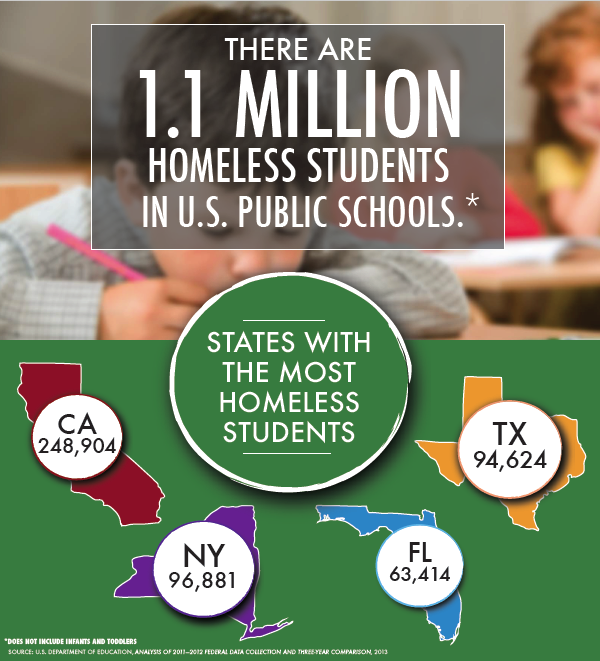

There are 1.6 million homeless children in the United States.

That one statistic was all it took to change my life.

I began taking pictures of homeless families in January 2012, hoping to put a face to the often invisible and forgotten people combating this growing issue. By documenting their daily struggles, I try to show the real people and real suffering that make up the much broader issue of homelessness.

Over the past two years, I’ve gained a lot of respect for these families. Being homeless is far from easy; it’s a 24/7 job that involves moving constantly from one shelter to another, looking for a job, and taking care of children.

There’s also the stigma surrounding poverty. Many people would like to believe that the situations of these families are their own doing. The reality, however, is that bad things happen to all of us, be it a job loss, illness, etc. The difference I’ve seen is that those who become homeless don’t have family or a social network to turn to for support when things go wrong. Many don’t know how or where to find the resources that are available to them or have barriers in the way of options they do know of.

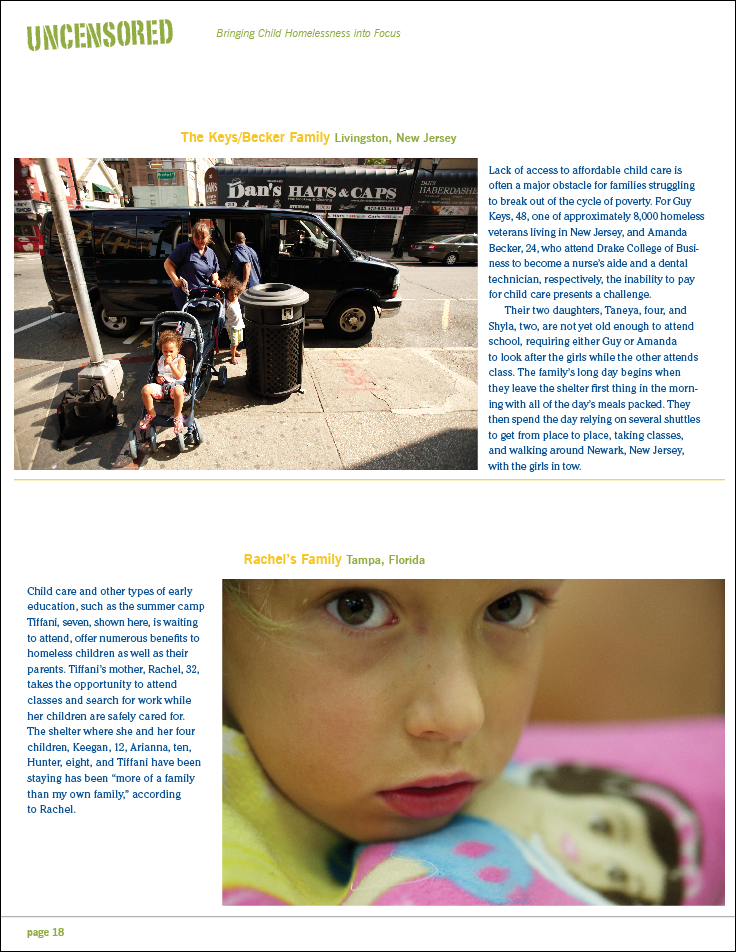

One of the issues I hear about most frequently from parents is the lack of affordable child care. You can’t get a job with kids in tow, but you can’t afford child care without a job, creating a Catch-22.

The result is tragic. The choice comes down to remaining unemployed and continuing a life of poverty and homelessness or leaving the children in the care of people they barely know, risking their safety in the process. I’ve been told stories of children who suffered physical and sexual abuse by the strangers taking care of them.

For the safety of these children, a lot of parents keep them holed up in motel rooms away from danger. Unfortunately, this tactic deprives children of necessary social interaction and mental stimulation.

The age before children even attend school is crucial in their development and future success, but oftentimes young homeless children are stunted in this development. How can children keep up with their peers academically when they face stressful living situations, have little parental involvement, and are continuously switching schools or missing days?

Homeless children are in need of positive role models in their lives. Many of these parents grew up poor or homeless themselves and are teaching their children the same behaviors and attitudes that kept them in poverty, continuing the cycle. One woman I met was never taught proper hygiene. She lost all of her teeth at a young age, adding to her difficulties in finding a job. How many other valuable lessons could she have learned with the right person to look up to?

Legislation to provide federal funding for universal pre-K has been introduced into Congress, following a plan touted by President Obama earlier in the year. (Although the legislation is currently stalled in Congress, the president recently proposed a budget for fiscal year 2015 that allocates $750 million in funds to pre-K programs.) This seems to be the best and most immediate solution available for the benefit of homeless children across the country. The option to send children to pre-K provides safe child care for parents and offers positive role models, education, social interaction, and development opportunities at a critical age for children—especially the vulnerable population of homeless children who need it the most.

We have a moral obligation to take care of the poor. My primary concern is to bring awareness to the plight of child homelessness and to allow others to witness the pain these children are dealing with on a day-to-day basis as well as their perseverance. My ambition is to create a sociological chronicle of this devastating moment in history through this visual endeavor—and for the world to recognize the unimaginable grief of child homelessness.

To download a pdf of this photo essay, click here.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

The Historical Perspective—

A History of Inequality in New York City

by Ethan G. Sribnick

Bill de Blasio, the new mayor of New York City, has made fighting New York’s poverty and inequality a focus of his young administration. While the percentage of the country’s wealth concentrated among its top earners has been on the rise for four decades, New York is one of the most striking examples of American inequality: among the nation’s 30 largest cities, it is home to the biggest income discrepancies. In 2011 the median household income in New York’s richest area, the Upper East Side, was $247,200. By contrast, in the city’s most impoverished neighborhood, the Coney Island section of Brooklyn, the figure was $9,500. The numbers speak for themselves.

De Blasio’s efforts seem aimed at undoing the policies of his predecessor, Michael Bloomberg, who, according to his harshest critics, turned Manhattan into a preserve of tourists and the wealthy. The inequality and poverty that de Blasio hopes to alleviate, however, have roots much deeper in New York’s past. The recently published book The Poor Among Us: A History of Family Poverty and Homelessness in New York City, which I coauthored with Ralph da Costa Nunez, documents the presence of poverty and inequality in New York from the eighteenth century up to today. A companion Web site, www.PovertyHistory.org, provides interactive maps, timelines, stories, and images so the user can explore the nature and experience of poverty in the city’s past.

A foreman in a box factory teaches a worker, Carmen Zapata, to operate a stamping machine in 1960s. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress.

There are many periods of inequality addressed in the book and Web site that suggest parallels to the scenario de Blasio faces. A look at the chasm of inequality created over the nineteenth century by the process of industrialization might reveal telling similarities to circumstances seen in the city today. Instead, this article will discuss a period of relative equality in the city’s past—the period beginning after World War II and extending through the 1960s—and explore the makeup of that more equal city. The “tale of two cities” that de Blasio now cites has its first chapter in the deindustrialization that ended the postwar boom and resulted in the service industries that still form the core of the city’s economy.

In the postwar era, that economy was based on manufacturing. As the city’s manufacturing base developed in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, New York did not come to resemble other industrial centers; the giant plants that were typical of Pittsburgh or Detroit, for instance, were never built in the city. Instead, with limited space, New York was peppered with many small-scale manufacturing shops. The secret to New York’s industrial success was its ready supply of labor and its flexible production capacity.

The apparel business, also known as the garment industry, formed one of the largest manufacturing sectors in the city and exemplifies the nature of production. Production of clothing required changes that would accommodate the new trends of each fashion season. It also called for highly skilled craftsmen to work closely with less-skilled and lower-paid workers. In New York, small firms, each specializing in a particular aspect of apparel production, were able to make limited quantities of garments at a fairly low cost. In 1947 the average-size garment-manufacturing shop in the city employed only 20 people. When more production was required, manufacturers culled more workers from the city’s ready supply of low-skilled labor.

Robert Moses and Mayor Robert Wagner take a housing tour. Moses’s plans to redevelop much of New York led to dislocation for many poor and working-class New Yorkers. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress.

For this system to be economically viable, a large pool of low-wage workers was needed. As the city’s garment industry grew, these workers were often recently arrived European immigrants looking to gain a foothold in the United States. In the 1940s the children of these immigrants still made up the majority of the city’s blue-collar workers. Yet, black migrants from the South who had begun arriving in New York in the 1910s and Puerto Rican migrants who had started to show up in large numbers in the 1940s were quickly joining the ranks of the working class.

With manufacturing dominating New York’s economy, the large number of workers involved in production dominated the city’s politics. Of the 3.3 million employed people living in New York City in 1946, 2.6 million could be considered part of the working class. With their husbands, wives, and children included, this working class formed the majority of the city’s population. The presence of powerful, politically engaged unions further increased the strength of the working class. As a result of all this, New York became a city with extensive publicly funded services, one described by the historian Joshua Freeman as a “homegrown version of social democracy.” This included an extensive transportation system, tuition-free colleges, hospitals, and even a radio station. The labor movement, with public support, created new cooperative housing complexes for workers and their families. New York City unions even built their own health clinics and, with government encouragement, helped oversee prepaid medical plans that covered workers’ health care.

The future of all of these public and semipublic programs depended on continued widespread employment and steadily increasing tax revenue. Unfortunately, at the same time that many of these programs were being put in place, manufacturing centers were beginning to move out of New York City. At first they relocated to suburban areas, where property was less expensive. In 1953, 56 percent of the metropolitan region’s manufacturing took place within the city limits; by 1966 the majority of those jobs were elsewhere. Many of the jobs lost were in the apparel industry, whose workforce shrank by 29 percent between 1950 and 1965. In an effort to keep work in the city, the unions made concessions that lowered salaries in this key industry. In 1950 garment workers made 10 cents per hour more than the average manufacturing employee in the city, but by 1965 they made 22 cents less per hour. The quality of life of people in these low-skilled positions began to decrease. Much of the burden of this economic decline fell on the black and Puerto Rican communities. As relative newcomers to New York, blacks and Puerto Ricans often had less union seniority and were frequently the first to be laid off.

The James Weldon Johnson Houses, a New York public housing project, is seen being built in 1947. When complete, the Johnson houses would cover the blocks from 112th to 115th Streets and from Park to Third Avenues in East Harlem, rapidly becoming a predominantly Puerto Rican neighborhood. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress.

The decline in manufacturing in the city was largely the result of national and global economic forces that made it less expensive to produce goods of similar quality outside New York. But choices made in urban planning and redevelopment, especially with regard to Manhattan, also contributed to the flight of production out of the city. The New York area’s first regional plan, developed in 1929, envisioned a Manhattan virtually free of industry, with manufacturing and port facilities moved to New Jersey and the outer boroughs. In the period after World War II, this vision for the city began to become reality. The urban redevelopment along the East River that occurred between 1945 and 1955—which included the construction of the United Nations, Stuyvesant Town, Peter Cooper Village, and, on the other side of the river, the Brooklyn Civic Center—led to the loss of 18,000 manufacturing jobs. This trend in urban renewal would continue. From 1954 to 1965, years that encompassed Robert Wagner Jr.’s tenure as mayor, 200,000 manufacturing jobs left the city.

The redevelopment of New York and the changing economy also had consequences for where New Yorkers lived. Urban renewal projects frequently failed to build the number of housing units they destroyed, and many of the units they did provide were more expensive than those they replaced. For example, according to Robert Caro’s biography of Robert Moses, the urban planner who oversaw many of these developments, the Lincoln Square urban renewal project, which built the Lincoln Center complex, destroyed 7,000 low-income units and built only 4,400 dwellings, 4,000 of which were luxury apartments. The movement of poor and middle-class communities out of most of Manhattan and into the upper reaches of the island and the outer boroughs had begun in the early twentieth century. But in the postwar era, projects such as urban renewal helped to push more struggling families to the outskirts of the city. A 1953 study found that 150,000 people, more than half of them black or Puerto Rican, would be dislocated by public works projects. While it is difficult to say in every case where those people ended up, the city saw a general movement of poverty out of Manhattan and other core areas and into neighborhoods in eastern Brooklyn and the South Bronx. As the maps on www.PovertyHistory.org demonstrate, this movement has continued in recent years. At the same time, neighborhoods in Manhattan have grown more affluent, with only a small number of poor residents.

The dislocation in work and housing experienced by many New Yorkers was the result of an economic transformation from a manufacturing economy to a service economy. This transformation would continue into the 1970s; between 1969 and 1977 the city lost an additional 600,000 manufacturing jobs, leading to declining wages for many who had once worked in that sector. The loss of work decimated many of the city’s working-class communities, leaving neighborhoods with high concentrations of poverty. The housing in many of these areas was destroyed by arson and neglect, and the safety of residents was threatened further by the drug trade and gang conflicts. Declining tax revenue, along with the city’s efforts to maintain the extent and quality of its services in transportation, education, and housing, would lead to the New York fiscal crisis of the 1970s and the eventual peeling back of social programs.

Boys play catch in a vacant East Harlem lot in 1954. Many of New York’s poorer neighborhoods would see an increase in abandoned properties and demolished buildings, especially over the 1960s and 1970s. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Today, the service economy is firmly in place in New York City. Of the 3.77 million New Yorkers in the workforce, only a little over 155,000, or 4.1 percent, work in manufacturing, and about 188,000, or 5 percent, have jobs in construction. The vast majority of the remainder are employed in some aspect of the service industry. The term “service industry,” however, encompasses a wide range of jobs. The fast-food worker is hardly in the same economic class as the Wall Street attorney. New York’s service economy is largely divided into low-skill, low-pay service jobs that often do not allow families to exceed the poverty threshold and high-paying jobs held by some of the wealthiest New Yorkers. This fact, which is at the root of the inequality in New York City, is what makes de Blasio’s challenge so difficult.

Some observers view the development of this bifurcated service economy as a tradeoff. They see the city’s choice to replace manufacturing and working-class housing with world-class political and cultural institutions in Manhattan—the U.N., Lincoln Center—as prescient; they view the subsequent efforts under Giuliani and Bloomberg to make the city accessible and welcoming as at least part of the reason that New York has not gone the way of Detroit. At the same time, as de Blasio has made clear, there are consequences for these choices, among them inequality and pockets of deep poverty. The Poor Among Us and www.PovertyHistory.org document this poverty, demonstrating its long history in New York City. As the de Blasio administration takes its first steps toward confronting this enormous problem, it would be wise to heed the lessons from the city’s past.

Resources

Poverty History Web site; www.PovertyHistory.org ■ Caro, Robert A. The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York. First Edition. Vintage, 1975 ■ Freeman, Joshua Benjamin. Working-Class New York: Life and Labor Since World War II. New York: New Press, 2000 ■ Noah, Timothy. “The United States of Inequality.” Slate, September 3, 2010 ■ Turetsky, Doug. “The More Things Change, the More They Stay the Same: Richest and Poorest NYC Census Tracts, 2000 & 2011 < IBO Web Blog.” ■ Warren, James. “Annual American Community Survey Shows New York City Has the Largest Gap of Income Inequality in United States.” New York Daily News, September 19, 2013. ■ Zipp, Samuel. Manhattan Projects: The Rise and Fall of Urban Renewal in Cold War New York. Oxford University Press, USA, 2010.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

Guest Voices—

Homelessness and the Law: A Community Comes Together to Defend Homeless Citizens of the Nation’s Capital

by Marta Beresin, Amber Harding, and Nassim Moshiree

The writers are staff attorneys at the Washington Legal Clinic for the Homeless, a District of Columbia nonprofit organization that advocates for the legal protection of those struggling with homelessness and poverty.

In the spring of 2013, District of Columbia mayor Vincent Gray proposed dramatic changes to the local laws governing homeless services. These changes threatened to turn back the clock on the rights of D.C.’s homeless residents and represented a troubling shift to an outmoded philosophy about the causes of and solutions to homelessness.

The Washington Legal Clinic for the Homeless (hereafter “Legal Clinic”), along with numerous allies who included both professional advocates and those who would be directly affected by the changes, succeeded in scaling back the most drastic elements of the mayor’s proposal, many of which were based on negative stereotypes and prejudices about people experiencing homelessness.

In this article, we examine the strategies employed, challenges faced, and lessons learned as a community came together quickly to stop a local government from infringing on the rights of its most vulnerable residents.

The Rise of Family Homelessness

From 2000 to 2012, D.C. lost half of its affordable rental stock, or 35,000 of its 70,000 units of affordable housing. The fair-market rent for a two-bedroom apartment in D.C. rose from $840 per month to $1,506 per month. The changes were due primarily to a combination of gentrification and federal and local cutbacks in funding for affordable housing.

At the same time that the cost of housing was rising, the Great Recession struck, causing D.C.’s poverty rate to rise to nearly 20 percent by 2010. Among children, the rate was even higher. By 2011, nearly one in three children growing up in D.C. was living at or below the federal poverty line.

The proposed laws reflected a shift backward to a view that the causes of poverty and homelessness are poor behavioral choices rather than structural forces beyond an individual family’s immediate control.

As a result of steeply rising housing costs and increasing levels of poverty, family homelessness rose 73 percent in D.C. from 2008 to 2012. But funding for homeless services and housing programs did not keep pace with demand during this period. Tax revenues were down, and the D.C. government’s resulting cuts most deeply affected programs that serve low-income residents, its least powerful constituency.

One example was the narrowing of families’ year-round access to shelter. District law mandates a right to shelter for all D.C. residents who are homeless when the temperature falls below 32 degrees Fahrenheit. Until the spring of 2011, the District’s policy was to shelter families who had no other safe place to stay, regardless of the temperature. Citing budgetary pressures, the District ended this policy, leaving families already in crisis without a safety net for much of the year, including on winter days when temperatures teetered close to freezing but were not below freezing, as required to trigger the legal right to shelter.

Family homelessness continued to grow. From 2009 to 2012 the number of families at D.C. General Emergency Family Shelter, the largest family shelter in D.C., soared. While just 53 families stayed there in April 2009, by April 2013, 285 families with nearly 600 children were residing at the shelter.

During this time, the Legal Clinic and other community allies increased the pressure on the District to resolve this crisis by highlighting stories of parents and children left outside or in other dangerous situations because they could not access emergency shelter services. In the winter of 2012–13, local media began to focus on the problem of family homelessness as well, highlighting both the magnitude of the need and the administration’s failure to respond to it with either shelter or housing resources.

It was in this climate that, in March of 2013, the Gray administration introduced a package of amendments to the Homeless Services Reform Act (HSRA) of 2005, the law governing homeless services in D.C., as part of its proposed FY 2014 Budget Support Act.

A Punitive Approach

The mayor framed these proposals as a way to stabilize families and help them move out of homelessness, but the amendments were almost entirely punitive in nature. They proposed to roll back many of the rights of homeless families and individuals and to increase the number of ways the government could deny access to emergency shelter services.

For example, the amended law would have allowed the District to place families in shelter “provisionally” while the D.C. Department of Human Services (DHS) determined the families’ eligibility for shelter or sent them to places other than shelter. The deputy mayor for Health and Human Services, Beatriz “B.B.” Otero, wrote that these provisional placements were meant to “keep families safe while they complete their assessment and explore alternatives to shelter,” “quickly reconnect or rehouse families using emergency or rapid rehousing funds,” and “allow the District to place families in shelter even during non-hypothermia periods.” Notably, nothing in the existing law prevented the District from sheltering families in non-hypothermic weather, and nothing in the proposed law guaranteed a right to such placements.

Many proposed changes to the District of Columbia’s policy were based on negative stereotypes and prejudices about people experiencing homelessness.

Moreover, “provisionally placed” families would stand to lose many legal rights that had protected families in shelter for years. According to the amendments, these families could be terminated from shelter or housing for rule violations with only 24 hours’ notice and without due process of law. They could lose other protections as well, among them the right to 15 days’ notice of termination or transfer, the continuation of shelter services during the appeal process, and all rights granted to those in temporary shelters—including the right to receive case-management services.

Another key feature of the amendments was that families could be terminated from shelter for turning down two offers of “rapid rehousing,” or housing with a short-term rental subsidy, regardless of whether the program or the particular unit was appropriate for the family. In other words, a family would not have been able to turn down two units—even on the grounds that they were unaffordable, were not wheelchair accessible, had egregious housing-code violations, were not the right size for the family, or were unsuitable for any other reason—without facing possible termination from shelter.

The amendments also proposed eliminating several important rights of tenants in supportive housing. Providers could create arbitrary time limits and terminate participants once they reached those limits, no matter the reason. The amended law also would have permitted D.C. to terminate supportive-housing tenants from the program for being hospitalized or otherwise institutionalized for 60 days or more.

Finally, the amendments proposed giving the mayor authority to mandate that shelter residents contribute to escrow accounts as a condition of receipt of shelter. That measure had been rejected in favor of a voluntary system when the Homeless Services Reform Act passed because of the high administrative costs, negative impact on staff/resident relationships, and inability of many shelter residents to contribute to escrow and still meet their basic needs. Under the proposed amendments, programs could terminate residents from shelter if they failed to place money in escrow each month.

Creating Meaningful Process Where There Isn’t Any

One thing was for sure: we needed to act quickly. The normal legislative process would have allowed plenty of opportunity to respond to the proposed changes. Normally, we would have had a chance to educate the community—including our advocate peers, providers, and, most importantly, our clients, who would be directly impacted—about the harm these amendments would do if enacted into law. By putting the amendments in the budget, however, the administration was assured a truncated review process, and there was a real danger that the amendments would be passed into law without a full public vetting: there would be no separate hearing on the proposed legislation, just one hearing on the entire Budget Support Act. The attention of those focusing on the budget would already be spread too thin for them to take in the amendments.

Faced with such a short time frame (a few months instead of up to two years), we saw that the proposed measures had to be taken out of the budget and put through the regular legislative process before we could address their substance.

In late April, the Legal Clinic and several key partners, including the D.C. Fiscal Policy Institute (DCFPI) and the D.C. Coalition Against Domestic Violence (DCCADV), drafted a sign-on letter to the mayor and D.C. Council citing our objections to the inclusion of such far-reaching proposals in the Budget Support Act without public vetting. We requested that the mayor withdraw the amendments from the FY 2014 Budget Support Act and allow the public a chance to have input. Councilmember Jim Graham, chair of the D.C. Council’s Committee on Human Services, agreed to hold a separate hearing on the proposed legislation if the mayor would remove it from the budget. The District’s own chief financial officer had certified that the proposed amendments would have no fiscal ramifications, and we argued that they were therefore not germane to the budget.

Nearly 200 organizations, including service providers, legal aid offices, and other advocacy organizations, signed on. The letter sent a clear message to the D.C. Council that there was broad community support for taking a careful look at these amendments.

Fighting the “Culture of Dependency” Myth

The administration’s official response to the sign-on letter was less than conciliatory. Otero issued a statement on behalf of the administration, arguing that the amendments were necessary to motivate families to leave shelter. She wrote, “Because families in shelter today pay no rent, no utilities, receive most of their meals for free, keep the full amount of their income, including TANF and food stamps, and receive many other supportive services, such as transportation and child care, there is a significant incentive for families to stay in shelter.”

Perhaps what was most disconcerting about the mayor’s proposals and the deputy mayor’s response was that they reflected a shift backward to a view that the causes of poverty and homelessness are poor behavioral choices rather than structural forces beyond an individual family’s immediate control, such as the steep rise in housing costs or the recession. During this period, the term “culture of dependency” became commonplace in policy discussions with the Gray administration. Officials claimed that the “cycle of poverty and dependence” was at the root of D.C.’s growing family-homelessness problem. The idea was that homeless parents were to blame for their own situations, and that if they were not making progress, they were probably not trying hard enough and they shouldn’t be rewarded with continued assistance.

A community came together quickly to stop a local government from infringing on the rights of its most vulnerable residents.

The deputy mayor’s response also attempted to pit homeless families against homeless individuals without children, a strategy that ultimately failed. She claimed that the administration would save $5.3 million by passing the amendments, and threatened that if they were not passed, “DHS will be forced to close these [three large singles] shelters outside of hypothermia season, beginning October 1, 2013.”

Both of these statements proved to be major missteps for the administration. First, there was the depiction of D.C. General—the District’s largest family homeless shelter—as a place where families are so comfortable that they have little incentive to leave, which struck us, our clients, and our allies as both laughable and offensive. For years, local media had detailed the poor conditions in which families were living at D.C. General, from overcrowding to heat and elevator outages to mold to inedible meals and more. And many of the “perks” that the letter mentioned, like free transportation and child care, did not exist at the shelter or elsewhere. Otero’s explanation of why there were so many families left at the shelter was based on harmful myths rather than the reality of the affordable-housing crisis and suppressed wages in the District. When families at D.C. General learned of the deputy mayor’s characterization of them, they began to organize and became committed to making sure their side of the story was heard.

Similarly, homeless individuals without children were tired of being threatened and pitted against families. The homeless advocacy group SHARC (Shelter, Housing and Respectful Change) began organizing shelter residents to attend meetings and rallies with the message that they both supported families and opposed shelter closures.

At the large hearing on the Budget Support Act a week after the sign-on letter was sent, a group of parents staying at the D.C. General shelter, several with kids in tow, read a statement of opposition to the proposed legislation on behalf of families at the shelter. They testified that they had not been afforded an opportunity to weigh in meaningfully on proposed changes to the law that would directly affect them, and they challenged the negative stereotypes on which the changes were based. The mothers insisted that families had every incentive to leave the shelter, but that many were encountering obstacles for reasons that were out of their control. They implored the council to remove the proposals from the budget and to invest in affordable-housing programs as a real solution to the families’ plight.

Councilmembers seemed sympathetic, and those whom we had already briefed about our concerns asked the mayor’s budget director pointed questions about why the amendments had been put in the budget when D.C.’s chief financial officer had certified that they had no budgetary impact.

The following Monday, the D.C. Council voted to remove the mayor’s proposal from the Budget Support Act. Councilmember Graham introduced it as stand-alone legislation—Bill 20-0281, the “Homeless Services Reform Amendment Act of 2013.” He announced that a hearing on the bill would be held in early June.

Mobilizing the Community

As a community, we had won a more open and transparent legislative process via a public hearing, but we had no time to celebrate, because the bill was still on a fast track under mayoral pressure. Along with some key partners, we continued our outreach to people who were homeless or in supportive-housing programs to inform them of the key provisions of the amendments. We encouraged them to voice their concerns via the upcoming June hearing and visits to the D.C. Council.

At an open informational session a week before the scheduled public hearing, we shared the Legal Clinic’s analysis of each proposed amendment, heard additional concerns about the substance of the amendments from the perspective of service providers and affected community members, and, together, developed a strategy.

The fight could not have been won without the active engagement of families and individuals who would have been directly affected by the regressive proposed policies.

At the June 3 hearing, which lasted for ten hours, more than 60 public witnesses testified against the bill and offered alternatives to the proposals.

The affected community in particular came out in force. Representatives of SHARC were very vocal and persuasive. Their message was clear: the proposals did nothing to solve homelessness and, worse, were based on unfounded stereotypes about people who are homeless, such as that people are poor because they don’t know how to manage their money. The message was one we had all espoused, but it had added resonance coming from them.

Most advocates, providers, and community members testified that the amendments should be withdrawn completely—that the proposed law would hurt, not help, people experiencing homelessness. Some testified that the underlying assumptions and premises of the proposals were flawed. Experts noted that some provisions violated basic constitutional due-process protections and federal antidiscrimination laws. For instance, the section proposing termination of tenants for stays in hospitals or institutions would have violated the civil rights of tenants with disabilities. (This legal testimony prompted Councilmember Graham to request that the District’s attorney general, Irv Nathan, look into the constitutionality and legality of some of the proposed bill’s provisions.)

The administration had made its own efforts to mobilize providers to support the bill at the hearing but had failed to educate them adequately on details of the provisions. For instance, several providers testified that escrow programs were helpful and therefore important to the residents of their shelters or housing programs. But upon further questioning, they admitted that they were in favor of escrow programs only if they were voluntary, and that they would not expel people from their programs for missing escrow payments, as the proposed amendment stipulated.

The public pressure worked. After the hearing, we were approached by representatives of the administration about setting up a meeting to explore whether there was any room for agreement between the two sides. A series of meetings with the D.C. Department of Human Services ensued, and large parts of the bill were dropped. Yet soon we reached an impasse.

We were able to obtain a meeting with the chairman of the D.C. Council, Phil Mendelson, at which we shared our remaining concerns and our impression that the mayor would not budge any further. Chairman Mendelson listened to our specific proposals and suggested that we try once more to reach agreement, intimating that only after significant additional effort on our part to reach an agreement would he intervene in the matter.

At the final meeting with the deputy mayor, representatives of the Department of Human Services, Councilmember Graham, and members of our coalition, we presented our positions and suggested possible compromises. A SHARC representative spoke eloquently about the hundreds of homeless people he had talked to about the misguided nature of the bill. He asked why, if the mayor was invested in solutions to homelessness, he was proposing only policies that left people out on the street instead of working to create good-paying jobs and affordable housing. The deputy mayor dismissed those comments, stating that there would be no further negotiation and that the mayor was personally committed to seeing the bill, as it stood, pass. The SHARC representative walked out of the meeting, while the rest of us wondered why we were there if no further work was to be done.

The deputy mayor’s complete dismissal of the community’s concerns and proposals left us free to realign our course in two significant ways. First, we were able to go back to our original positions on the provisions instead of proposing compromise language. Second, we could now report to Chairman Mendelson that we had done our very best to work out a compromise but had found the administration to be unyielding. Probably noting our good faith efforts, the broad coalition we had amassed, the substantive concerns we had raised, and the positions of D.C. councilmember Graham and other councilmembers, which were more progressive than those of the mayor, the chairman redlined the bill himself and took out or ameliorated every one of the sections with which we still had concerns.

In another stroke of good of luck, three days before the scheduled vote on the bill, the District’s June revenue forecast revealed a surplus of $92.3 million for FY 2014. This disproved the administration’s claim that it would have to close singles shelters if the legislation did not pass.

A Triumph of Community Teamwork

The bill that was passed at the June 27 council hearing was a vast improvement over the original. Many of the most punitive sections of the mayor’s proposed law were removed entirely from the final version, including the provisional-placement scheme, time limits for housing, and an expanded list of grounds for termination from supportive housing.

Other sections of the original bill were greatly improved. The law now gives the mayor authority to develop a mandatory savings program, but an individual cannot be kicked out of shelter for failing to save money. Similarly, a shelter resident cannot be threatened with termination for failing to accept a rapid-rehousing unit that does not meet his or her household’s specific needs. Finally, the section that would have allowed terminations of participants in supportive housing was altered to protect the rights of people with disabilities and to extend the right to return to housing after absences.

This process was an example of the power of communities to safeguard the rights of their most disenfranchised members. At the start of this journey, the administration had the advantage of power, influence, and, at the beginning, control of the message. We faced setbacks along the way, but it was a testament to the strength of our relationships with our allies that we were able to adapt and shift strategies in a timely way. Finally, this fight could not have been won without the active engagement and participation of those residents, both families and individuals, who would have been directly affected by the regressive policies in the mayor’s original proposal.

Resources

Washington Legal Clinic for the Homeless; http://www.legalclinic.org/ Washington, DC ■ DC General Emergency Family Shelter, Washington, DC ■ DC Department of Human Services http://dhs.dc.gov/ Washington, DC ■ DC Fiscal Policy Institute; http://www.dcfpi.org/ Washington, DC ■ DC Coalition Against Domestic Violence; http://www.dccadv.org/ Washington, DC ■ SHARC (Shelter, Housing and Respectful Change) Washington, DC ■ DC Fiscal Policy Institute, Disappearing Act: Affordable Housing in DC Is Vanishing Amid Sharply Rising Housing Costs, May 7, 2012 ν U.S. Census Bureau, Income, Poverty and Health Insurance Coverage in the United States: 2010, September 2011 ■ DC Action for Children, DC Kids Count Report, February 2012 ■ Petula Dvorak, “600 Homeless Children in DC and No One Seems to Care,” Washington Post, February 8, 2013 ■ Brigid Schulte, “DC Council Strips Controversial Homeless Proposals from Budget,” Washington Post, May 13, 2013 ν Mike Debonis, “Another Revenue Windfall for DC Government,” Washington Post, June 24, 2013.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

Conferring on Homelessness—

Beyond Housing: The ICPH 2014 Conference

by Clifford Thompson and Elizabeth Ezratty

ICPH’s 2014 conference, Beyond Housing: A National Conversation on Child Homelessness and Poverty, took place in New York City from January 15 to 17. The conference’s approximately 450 attendees were able to choose from among 40 “breakout” sessions, with topics ranging from outreach for LGBTQ youth, to collaborations between homeless-services departments and day care centers, to the participation of homeless individuals in advocacy efforts.

The conference featured three stirring keynote speeches. ICPH president and CEO Ralph da Costa Nunez gave the first, on January 16, citing history to make the case for what he called “a regulatory system for poverty.” The programs that grew out of President Lyndon Baines Johnson’s Great Society, he noted, alienated many people who saw them as intrusions into their lives—with children bused to schools in other neighborhoods in efforts toward integration, for example, or low-income housing built in middle-class neighborhoods. That alienation set the stage for the election of Ronald Reagan, who presided over a dismantling of social programs that, despite their shortcomings, constituted much of the safety net in the U.S. That dismantling, Nunez said, contributed heavily to the current homelessness problem. Discussing the importance of that government safety net, Nunez pointed out that without such programs as food stamps, Medicaid, and Medicare, the current poverty rate of 16 percent would be closer to 32 percent. The lesson to be drawn from this, according to Nunez, is that while some programs have been flawed, the solution is not to end all programs—that the U.S. needs neither “big government” nor smaller government but good government. Nunez also argued that homelessness is a multidimensional problem with numerous causes and therefore cannot always be solved through rapid rehousing; he stressed the need not only to house families but to help them improve their overall circumstances to the point at which they are self-sufficient. He drew applause with the line, “Our job isn’t to get homeless people off the street. It’s to get homeless people on their feet.”

Author, educator, and MSNBC host Melissa Harris-Perry gave a very well-received, humor-filled but trenchant lunch keynote on January 16. Posing the question “Why are people poor?”, Harris-Perry noted that race is “strongly determinative” when it comes to suffering from poverty. Discussing her own success, she explained that she came of age in a time of “high-quality, integrated public schools” and benefited from “aggressive affirmative action” programs. She pointed to historical as well as contemporary structural barriers to success for many racial minorities, from the decision to let states choose who received housing loans—a policy that worked against southern blacks—to a judicial system that in some states leaves up to ten percent of black adults incarcerated, because “the real crime is being poor.” Structural barriers, she said, are as much a cause of poverty as individuals’ life choices. Addressing those barriers, Harris-Perry added, requires political will. She also pointed out that a political coalition between blacks and middle-income whites would serve both groups, since those whites have more in common with blacks, economically speaking, than they do with higher-income whites. In addition, she set out to puncture myths, explaining, for example, that there is little demonstrated connection between poverty and the so-called marriage dearth, since the marriage rate has seen a steady drop while the poverty rate has been much more erratic.

On January 17 Nikki Johnson-Huston gave the final keynote, recalling her journey from homeless child to successful Philadelphia-based attorney. She told her spellbound audience that she had entered the shelter system at age nine, and that she had learned the importance of service from her grandmother, who had later taken care of Johnson-Huston when her own mother could not. Johnson-Huston described herself as “the legacy of [her] grandmother” and of “the social safety net.” She recalled that during her time in shelter, she loved to visit libraries—warm, comfortable places where books fed her imagination and her dreams. Johnson-Huston went on to college, and though she struggled there, due to a low self-image from having been homeless, she later worked as a live-in nanny for a kind family who helped her to pursue her ambitions. Johnson-Huston’s brother, she revealed, had not been as fortunate, having entered foster care because his grandmother could afford to take in only one child. The path her brother took as a result contributed to his early death. While grieving for him and carrying a burden of guilt, Johnson-Huston discovered a community of people who had greatly valued her brother, which led her to realize how much human life and potential are wasted when families are broken up because of poverty. She urged advocates and government officials to “please try to keep families together.”

Conference breakout sessions included “Working to End Homelessness: Best and Promising Practices of Employment Interventions for People Experiencing Homelessness.” In this session, Chris Warland and Caitlin Schnur of the Chicago-based National Transitional Jobs Network explained that employment is a significant determinant of health and that people need not be “100 percent employable” to begin working. For example, if an alcohol-dependent person can refrain from drinking while on the job, that person can be employed, even if he or she is not yet ready to stop consuming alcohol at other times. The philosophy behind transitional jobs, Warland and Schnur explained, is “meeting people where they are.” Another session was titled “The Role of Emergency Housing in Promoting Stability and Sustained Recovery in a Housing-First World.” During that session Elizabeth von Werne and Holly Woodbury of Miami’s Chapman Partnership recalled the organization’s founding by Alvah Chapman in the early 1990s, and they described its continuing, successful work in enlisting employers, local government, volunteers, and faith- and community-based organizations to provide an “ecosystem of support” for homeless individuals and families. A network of local organizations is also integral to the work of the COMPASS Community College Collaborative, a Massachusetts program that was the focus of another breakout session. Jodi Wilinsky Hill of COMPASS for Kids and Susan Leger Ferraro of Inspirational Ones, which serves disadvantaged youth, described their success in promoting education and job-readiness training for parents who are homeless or at risk of homelessness.

In a departure for the Beyond Housing conference, on January 17 ICPH staff led separate, hour-long breakfast discussions, each devoted to a different question regarding poverty and homelessness. Conference attendees were free to participate in discussions of their choice. Deb Ellis, executive director of the New Jersey Coalition to End Homelessness, and Jan Edgar Langbein and Jon Edmonds of the Dallas-based service provider Austin Street Center were among the participants in a discussion focusing on the questions, “With respect to national and local plans to end homelessness, what does the end of homelessness actually look like? What are the goals, and are they realistic?” The discussion yielded agreement that the “end of homelessness” would mean that all who wanted to access homeless services could do so, and that there would be no unsheltered homeless individuals or families. Ellis argued that ending homelessness could not be done solely by government and that communities must be involved, which led Edmonds to suggest the term “community first” as a slogan emphasizing the importance of shared responsibility for individuals, families, and neighborhoods. Another breakfast discussion centered on community experiences with rapid rehousing programs for families. Conference attendees from Nashville, Tennessee; Lowell, Massachusetts; Arlington, Texas; Ann Arbor, Michigan; and Des Moines, Iowa, discussed the challenges of rapidly rehousing families in their respective communities as well as successes some had seen through that approach. Those finding fault with rapid rehousing noted that providers were often required to have significant liquid assets on hand to cover the lag time between rent payments to landlords and reimbursements to providers. They also expressed frustration with the shift in funding priorities in favor of rapid rehousing at the expense of transitional-housing providers. Proponents of the strategy felt that in their communities, rapid rehousing allowed providers to do more for their families with less money. Participants in the discussion agreed that under the right circumstances and with appropriate targeting of funding and case-management resources, rapid rehousing can work for some families.

Another special feature of the Beyond Housing conference was the exhibit on January 16 by the internationally published photographer Craig Blankenhorn. The photographs document the experiences of some of the 1.6 million homeless children in the U.S., in regions as disparate as Las Vegas, Florida, and New Jersey. Blankenhorn’s often heartbreaking images depicted children of different races, all suffering the effects of housing instability. For conference attendees who saw the exhibit, the photographs were a poignant reminder of why they were gathered in New York City, and whom they had come together to serve.

For videos, presentation footage, and additional information related to the Beyond Housing conference, see the ICPH Web site at www.ICPHusa.org.

Resources

National Transitional Jobs Network; http://www.heartlandalliance.org/ntjn/ Chicago, IL ■ Chapman Partnership; https://www.chapmanpartnership.org/ Miami, FL ■ COMPASS for kid;s http://www.compassforkids.org/ Lexington, MA ■ Inspirational Ones; Lawrence, MA ■ New Jersey Coalition to End Homelessness; http://www.njceh.org/ Roseland, NJ ■ Austin Street Center; Dallas, TX.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

On the Record—

The State of Children’s Mental Health and Associated Costs of a Fragmented System

UNCENSORED: Given the dangers that mental health problems in childhood pose for success in adulthood, what is being done to address the issue?

WOODLOCK: There is little in the way of an overarching national public policy concerning mental health among children. This is in spite of the fact that while one out of ten children has a serious emotional disturbance, only 20 percent of those kids ever receive treatment. Children with mental health issues have the highest school-dropout rate among all disability groups, and only 30 percent graduate with a standard high school diploma. Sadly, more children suffer from psychiatric illness than from leukemia, diabetes, and AIDs combined.

Progress has been made to address the needs of these troubled children more comprehensibly. Spurred by the Systems of Care initiative introduced by SAMHSA (the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration) in the mid-1980s, states now recognize that emotionally troubled children often face a multiplicity of issues:

- Up to 75 percent of children in juvenile justice settings suffer from mental illness.

- 50 percent of kids in the child welfare system have mental health problems

- 21 percent of low-income children suffer mental health problems

UNCENSORED: What else should be done?

WOODLOCK: Several government organizations have evolved to deal with these so-called “cross-system kids,” in areas including substance abuse, education, child welfare, child development and heath, and juvenile justice. But the truth is all troubled children are cross-system kids, and the very systems created to address their multiple needs separately do so ineffectively. Departments operate in silos and rarely interact with each other, resulting in a fragmented approach that is both costly and inefficient. Efforts such as the Family Movement have exposed the overwhelming task that parents and caregivers face in having to deal with so many organizations just to get minimal help.

Today, with the move to Medicaid Managed Care to contain costs, we should be concerned lest we take a giant step backward in our thinking about public policy with regard to troubled children and the funding to address their needs.

UNCENSORED: Considering the need to contain costs, what approach should be taken?

WOODLOCK: Yes, it is expensive to treat a cross-system child when you consider the breadth and the depth of fragmented and often duplicative services whose practitioners don’t necessarily communicate with one another. Until substantive changes are made to address the lack of integration, we will continue to see a rise in the number of youth becoming adults who need services. Many continue to view the systems for adults and children as separate and distinct; however, the same initiatives that work so well in the adult system—coordinated care among agencies to address multiple difficulties—should be applied to the whole children’s system. Early behavioral interventions can improve health care and save money. When these approaches are applied to children, the improvements are ten-fold.

Dealing effectively with children’s multiple issues while they are still young can go a long way toward preventing future problems such as homelessness, substance abuse, unemployment, and crime. More than half of adults who were in foster care have an Axis I diagnosis [for example, a diagnosis of schizophrenia or a mood disorder], an employment status well below that of their peers, and a rate of post-traumatic stress disorder, or PTSD, twice that of combat veterans. Imagine what could have been done with effective early treatment.

Rather than turning to Medicaid expenditures alone, states should look more broadly with regard to children’s mental health. Targeted behavioral health interventions can improve outcomes and reduce expenses for child welfare, education and special education, juvenile justice, and more. For example, Maryland, New Jersey, Oklahoma, and Rhode Island have all employed a “wraparound” approach to customizing services for troubled kids. These states have implemented changes in policy, services, financing, and training in order to expand their systems of care so that more children and their families can benefit.

Resources

Institute for Community Living; New York, NY ■ National Center for Children in Poverty, Children’s Mental Health: What Every Policymaker Should Know, 2010 ■ National Technical Assistance Center for Children’s Mental Health, Expanding Systems of Care: Improving the Lives of Children, Youth, and Families, 2012 ■ New York State Children’s Plan 2007.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

Databank

Download the Databank here.

U.S. Department of Education; http://www.ed.gov/ Washington, DC.

To download a pdf of this article, click here.

The National Perspective—

Preventing Homelessness among Foster Care Youth through Discharge Planning

by Matt Adams and Anna Simonsen-Meehan

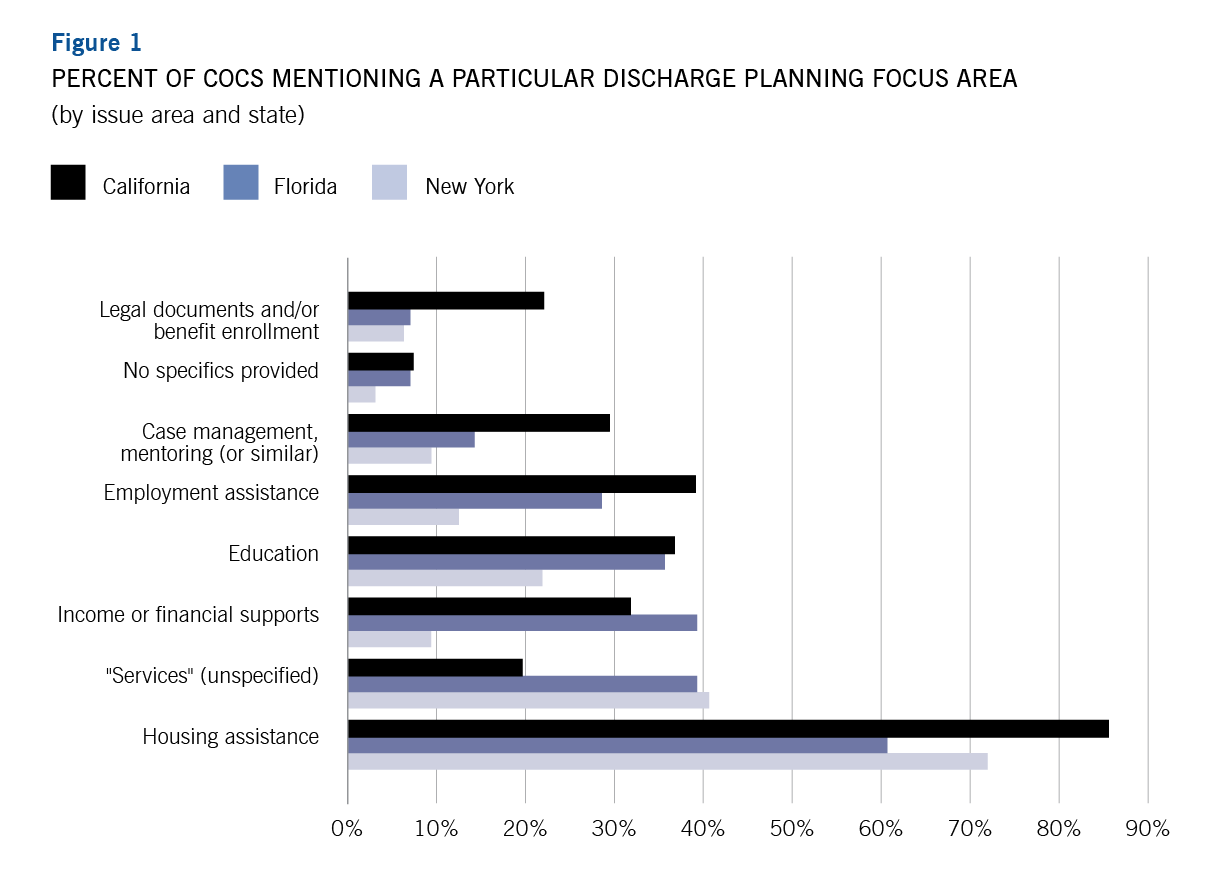

Each year, approximately 23,000 to 30,000 youth across the country “age out” of the foster care system, also known as “emancipating.” Unprepared for independent living and lacking the social supports afforded to youth living in stable families, many become homeless immediately following exit and are also at risk of experiencing housing instability later in life. In one large-scale study, two-fifths (42%) of youth were homeless within two years of exiting the system, while researchers estimate that anywhere from 10% to 40% of homeless adults have formerly been in foster care. Preparing foster care youth for stable independent living is an essential component of curtailing both youth and adult homelessness.

“Aging out” and “emancipating” refer to the process of leaving the foster care system upon reaching the age of majority—most commonly age 18—instead of receiving placement in a permanent home through reunification with parents, adoption, or placement with relatives.