a policy report from ICPH

December 2015

At present, more than 12,000 families and about 23,000 children reside in New York City homeless shelters. These are some of the highest numbers ever recorded, despite efforts under several mayoral administrations to stem the tide. New York City has built more affordable housing, has dispersed more rental vouchers, and has established more prevention programs than any other city in the country. So, why, after 30 years, do the number of families residing in shelters continue to grow?1

For decades, city government combated family homelessness with a singular approach—short-term access to low-income housing. This approach does not effectively address the needs of the majority of homeless families who struggle with barriers of poor educational attainment, domestic violence, chronic health conditions, or lack of work experience, among others. The city’s one-size-fits-all approach has resulted in many of these families returning to the shelter system. Despite increased spending and resources over time, the demand for shelter has only increased. Unless policymakers confront the multi-faceted problems that lead families to enter and return to the shelter, their numbers will continue to rise, as will the costs associated with caring for them. This report reviews twenty-five years of family homelessness in New York City and the various policy initiatives instituted to combat it. In conclusion, it suggests an alternative path to reducing what has been one of the city’s most intractable social problems.

The Growth of Family Homelessness in New York City

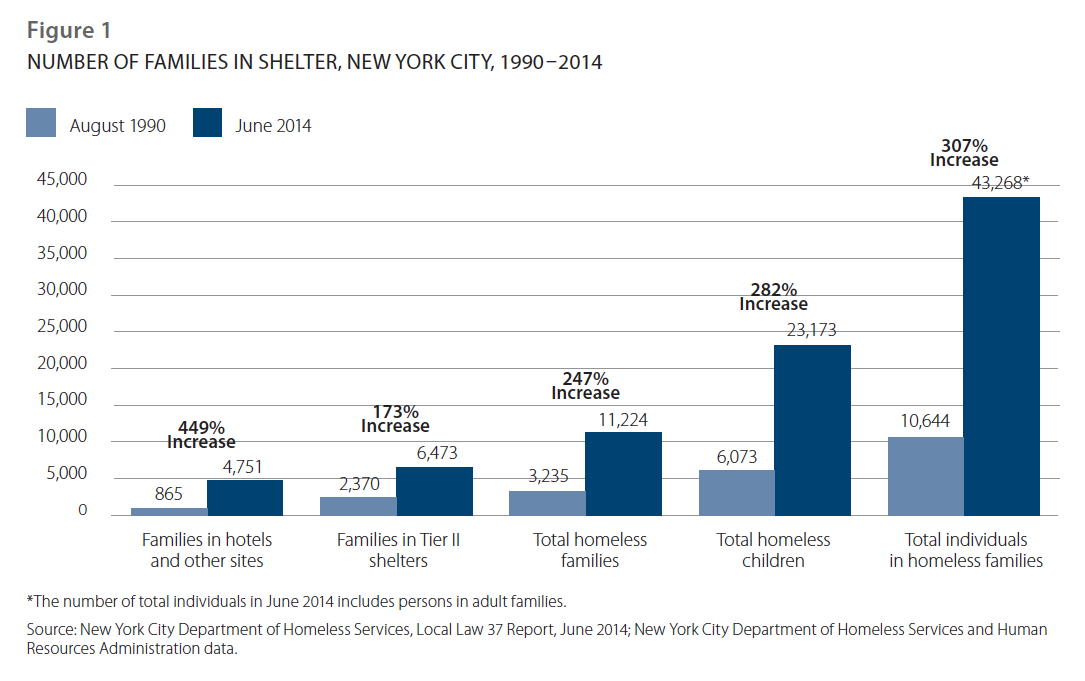

Family homelessness has more than tripled in New York City since 1990. Families with children residing in shelter increased 247% from 1990 to 2014 and the number of children in shelter grew even faster, jumping 282% (Figure 1). Families are now the largest segment of New York’s homeless population, with over 43,000 adults and children residing in city shelters.2

As the number of homeless families has risen, so too has the number of facilities serving them—150 in May 2014, including transitional (Tier II) shelters. In 1988 there were 33 Tier II shelters; by 2014 that number had risen to 90. In addition, a greater percentage of homeless families than ever before are being housed outside family shelters. In 1990, 26.7% of homeless families with children were staying in hotels and other non-shelter locations; by 2014 that proportion had grown to 42.3% and included families living in private apartments leased through the city at above-market rates. This type of housing, known as “cluster site” apartments, is often criticized as expensive, but efforts to reduce payments have met with resistance from participating landlords, some even going so far as to close down their cluster-site facilities in response.3

Affordable Housing, Rental Vouchers, and Prevention Efforts: Good but Not Enough

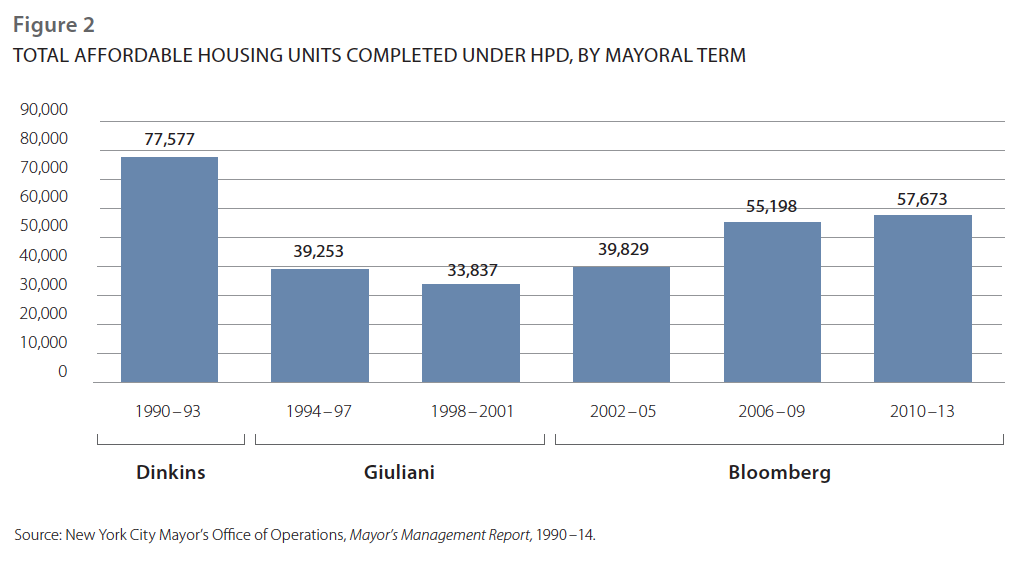

Over the last 20 years, the city has tried to alleviate homelessness by increasing the amount of affordable housing. The Department of Housing Preservation and Development’s (HPD) rate of construction and preservation dipped after a high of 77,577 units were brought on-line in the early 1990s, but was reinvigorated under the Bloomberg administration’s 2005 New Housing Marketplace Plan (Figure 2). Despite this effort, the benefit to families struggling with homelessness was limited, as 68% of the new housing was intended for low-income households—who under the plan included families of four making up to $56,700. With the bar for “affordability” set so high, Bloomberg’s housing push ended up excluding many extremely low-income renters, such as families exiting shelter.4

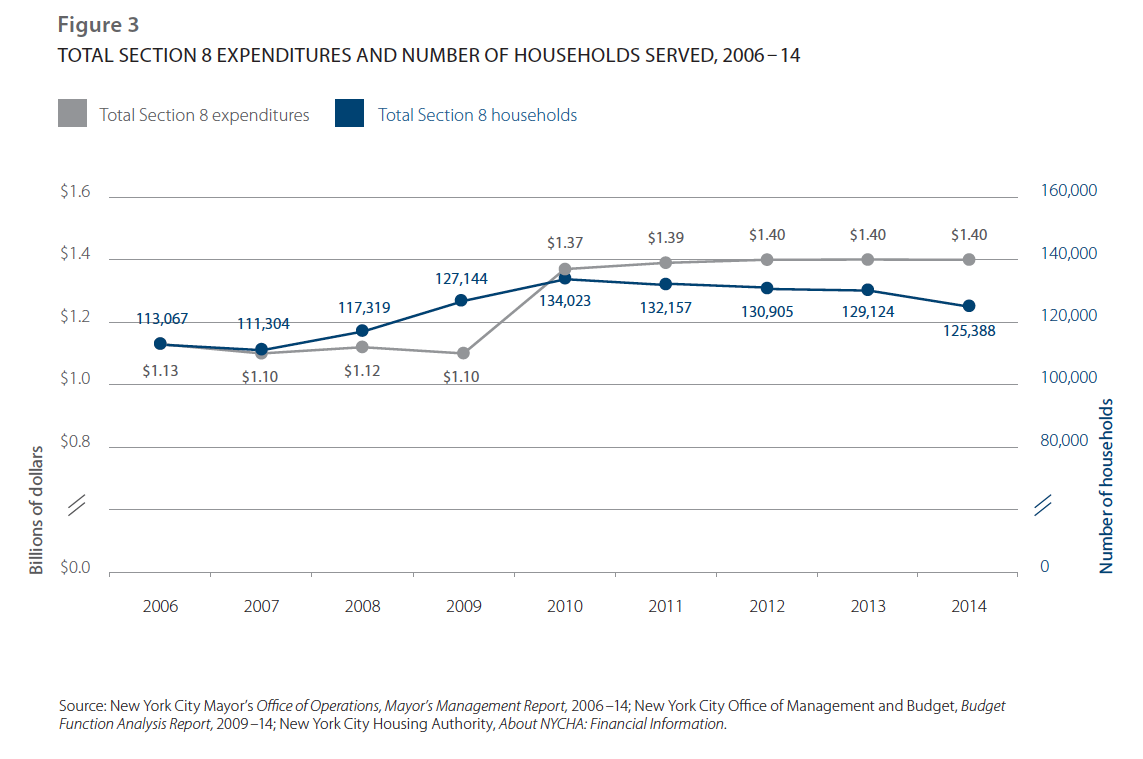

While these families would be eligible for Section 8, the federal rental-subsidy program, this program has seen its costs increase faster than the number of people it is able to help. Between 2006 and 2014, the total expenditures on vouchers increased by 24%, while the number of households utilizing Section 8 rose by only 11% (Figure 3). The waiting list in New York currently has almost 122,000 households and is closed to new applicants. Re-prioritizing homeless families for Section 8 was part of the de Blasio administration’s 2014 housing plan, but the already-full program has yet to show that it could accommodate the thousands of families in shelter. In FY 2015, the New York City Department of Housing Preservation and Development issued 500 new vouchers to homeless households, which helped to slow the growth of the family shelter population to 2% by July of 2015.5

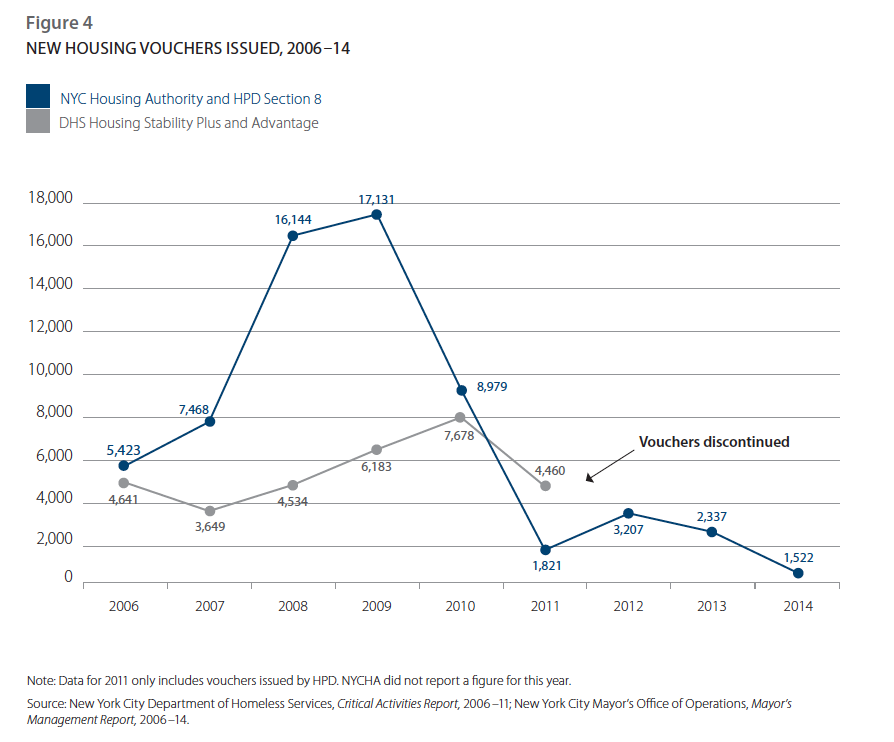

Starting in 2005, the Department of Homeless Services (DHS), began providing short-term rental vouchers to homeless families, first through Housing Stability Plus, and then through the Advantage programs, all of which have been discontinued. At its height, Advantage helped 7,678 families exit the shelter system annually (Figure 4), although the number who had entered shelter specifically hoping to receive a voucher is unknown. Even at the height of their availability, more housing vouchers were insufficient to curb homelessness, and 5,105 more families entered shelter in 2010 than in 2008. Since August 2014, the city and State have implemented a series of short-term voucher programs, dubbed Living in Communities (LINC), aimed at specific homeless groups, such as working families, families who have been chronically homeless for at least two years, and victims of domestic violence. While LINC was better-targeted than its predecessors, whether or not it will be able to keep families from returning to shelter and maintain housing long-term remains to be seen.6

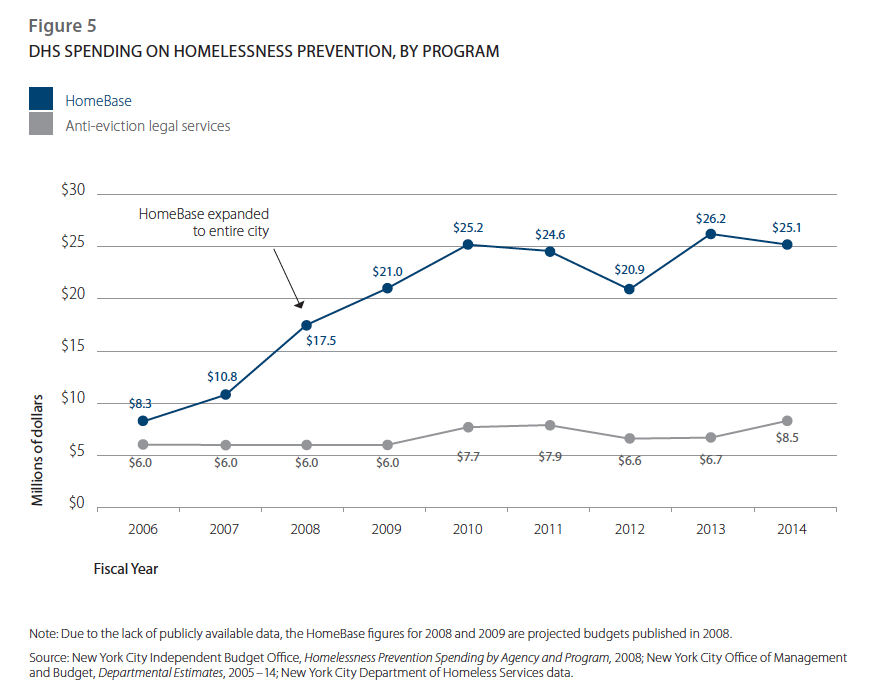

In addition to its efforts to create affordable housing, the city spends millions of dollars each year on prevention programs to keep at-risk families from entering shelter. During FY 2015, the DHS’ HomeBase program (which offers cash-management and financial assistance to eligible families) expanded to nine new locations (for a total of 23 sites) and increased funding to $42 million. In FY 2014, 12,131 individuals enrolled in HomeBase. That same year, the family shelter population increased by 3%.7

The Consequences and Costs of Past Efforts

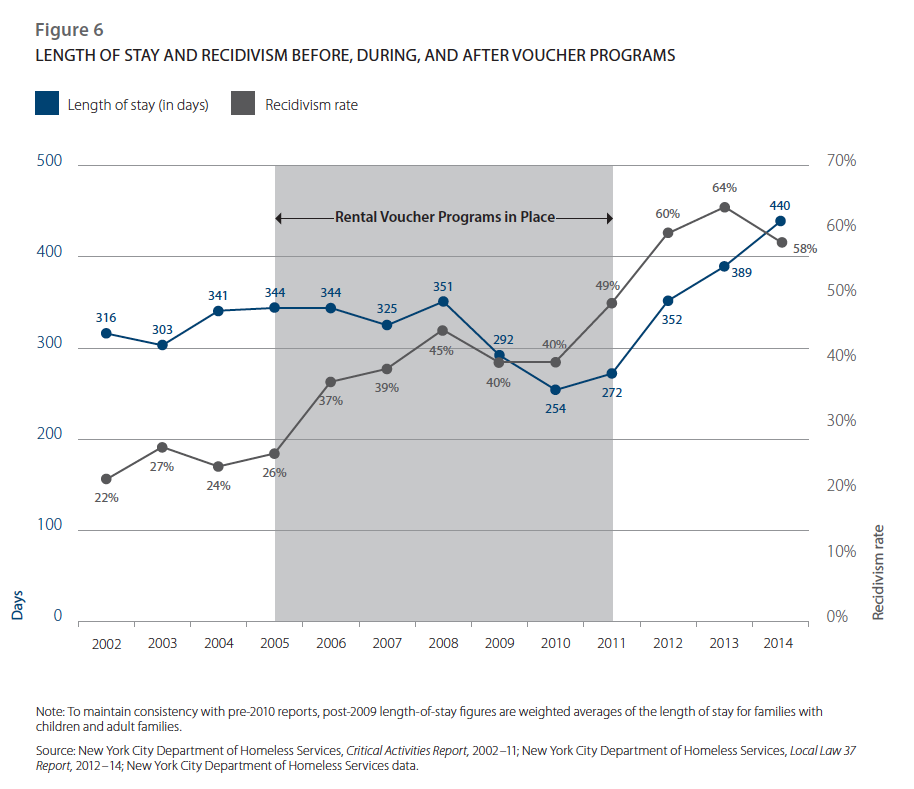

Some of the programs discussed earlier have led to negative consequences for families in shelter over the last decade. Since 2002, the average length of time a homeless family spent in shelter has increased by 39%, from 316 days to 440 (Figure 6). The rate at which families return to shelter has also gone up, with 58% of those applying for shelter in 2014 reporting a previous episode of homelessness. In 2002 this “recidivism” rate was only 22%. Both the average length of stay and the recidivism rate improved temporarily with the availability of short-term rental subsidies, but these decreases did not survive the end of these programs.

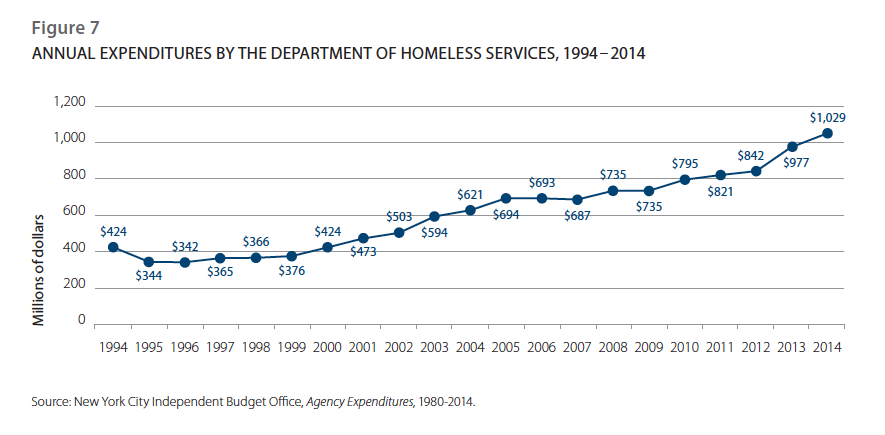

With trends continuing in the wrong direction and more families entering shelter, the cost of these strategies has been high, with New York City now spending more than a billion a year on homelessness. From 1994 to 2014, the city spent $12.8 billion on homeless services. Since its inception in FY 1994, the total budget for DHS has risen by 143%, with an average annual increase of $30.2 million (Figure 7). In FY 2014, 51.1% of all departmental spending went toward family shelters (including both families with children and adult families with no minor children). The rate at which the city is spending money to combat homelessness may be holding off an even worse increase.8

“A New Path” to Reverse Historic Trends

This report demonstrates that past attempts that focus only on housing to address family homelessness have led to rising shelter numbers and increasing costs. With no sign that the current crisis will decline on its own, it is time to recognize that family homelessness is more than just a housing issue; a one size policy does not fit all when it comes to solving the homelessness crisis the city is facing. Homelessness is a multi-faceted issue that requires a multifaceted solution, one with services targeted to families’ specific needs. For decades, the city has tried to make families fit the system; now we need to make the system fit the special needs of families.

To truly break the cycle of family homelessness, a fresh strategy is needed that redefines the role of shelters in helping homeless families return to their communities permanently. The city has the opportunity to transform the current shelter system into a single, comprehensive network of support services, capable of addressing families’ specific needs with a view toward their long-term housing stability and independence. Understanding that not every family faces the same challenges, a triaged family-shelter system could be instituted to provide a range of service-delivery options.

Level 1 of this system would consist of short-stay facilities. If rapid-rehousing strategies are used appropriately and rental-subsidy programs intelligently, families who simply need a chance to get back on their feet can do so within an approximate 30- to 60-day window. This step alone would immediately take pressure off the system, by rapidly rehousing families who can transition from shelter successfully.

Level 2 would comprise an array of more specialized facilities with lengths of stay up to six months. A transitional program would allow those families who need more structure a little extra time to learn or relearn valuable skills and stabilize their situations. Those families would be readied for re-employment and independent living and moved out of shelter as soon as they were ready to go.

Level 3 would consist of a network of highly technical facilities to serve the chronically and long-term homeless, the most frequent users of public assistance, and the hardest to help. These facilities would provide intensive, specialized services to help families tackle the complex causes of their own homelessness, such as domestic violence, insufficient education and employment skills, and the effects of child welfare and neglect, among others. The lengths of stay at these sites could be as long as 12 months or more, if need be. The increased length of stay and its cost will in the long run be more cost effective than simply rehousing families because they will be equipped to maintain their housing permanently without a government subsidy.

Such a restructuring of family shelters would result in a system that is more manageable, cost-efficient, and successful in permanently moving homeless families into housing. If services are targeted according to need, families will not move out of shelter faster; they will be more likely to remain out of shelter permanently. The housing-only strategies of the past 30 years have had limited success in reducing family homelessness. It is up to the city to seize this opportunity and use its power to transform its homeless family policies and move an antiquated shelter system into the 21st Century. The time for bold new action is now.