a policy brief from ICPH

April 2015

Homelessness is now so pervasive in New York City that it directly affects roughly one out of every 13 public school children. Over 83,000 students enrolled in city public schools in school year (SY) 2013–14 were identified as homeless—on average, every classroom has at least one homeless child.1 However, homelessness is not only confined to those students living in shelter. More than half of those 83,000 homeless students are living doubled up in someone else’s apartment due to loss of housing or economic hardship. This brief examines the growth in doubled-up students across the boroughs between SY 2010–11 and SY 2012–13 and the significance it has for city policies.2

Growing Off the Chart

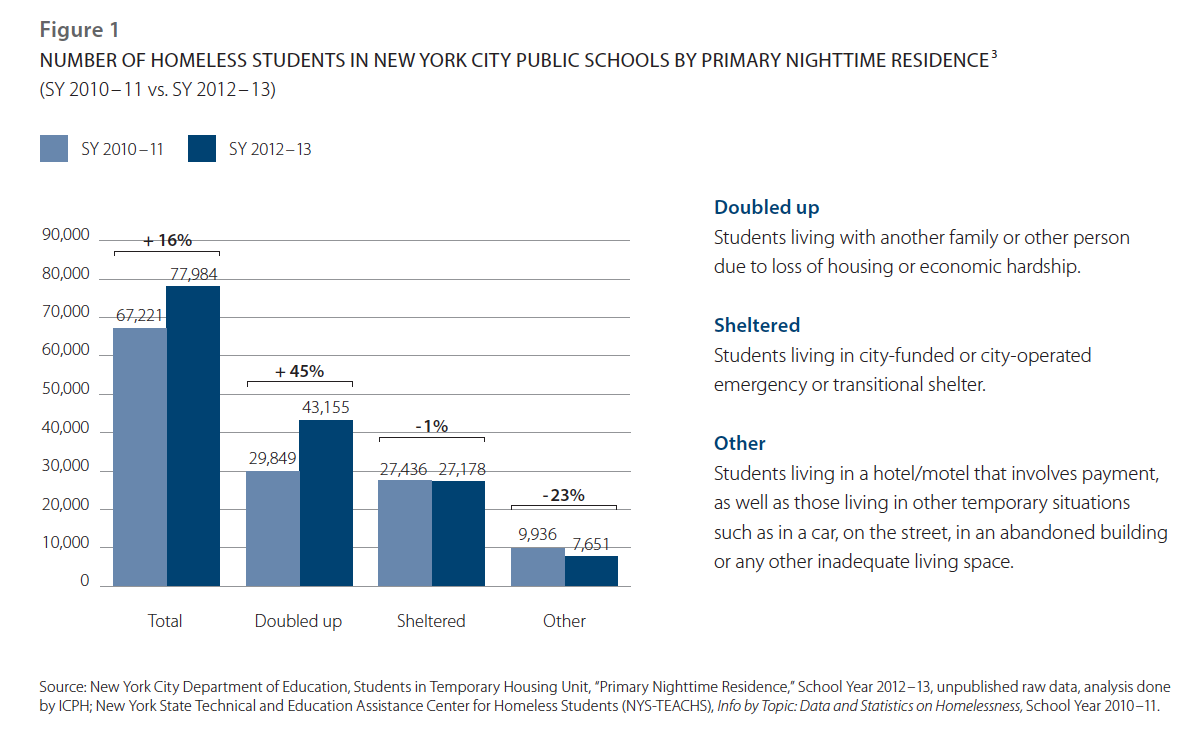

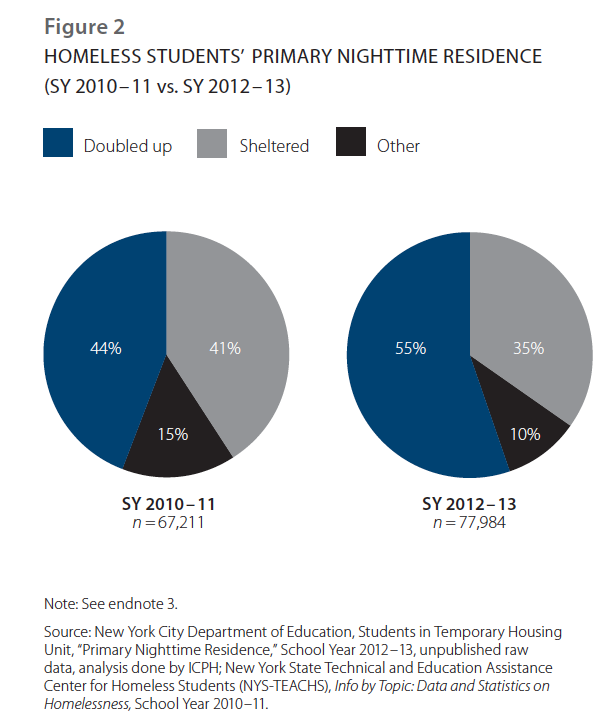

Every year, more of New York City’s school children experience homelessness. It is a reality that impacts families in every school district and borough across the city, with the number of homeless students increasing by 16%, from 67,221 to 77,984, in just two years. This growth is not necessarily the result of an increase in the public school population overall; during the same period, total student enrollment remained roughly the same. Likewise, an increase in the number of students living in shelter does not necessarily explain the trend. Between SY 2010–11 and SY 2012–13, the number of homeless students who reported their primary nighttime residence as a shelter remained almost the same, at 27,436 versus 27,178. This is reinforced by the fact that very little capacity was added to the family shelter system, so the number of homeless students living in shelter remained essentially the same. Growth during this time period was primarily the result of a significant increase in the number of homeless students living doubled up, with a net increase of more than 13,000 doubled-up students attending school in SY 2012–13 than in SY 2010 –11 (see Figure 1). This increase occurred not only in number, but also in the proportion of homeless students living doubled up; roughly 44% in SY 2010–11 compared to 55% in SY 2012–13 (see Figure 2). While some of this growth is likely due in part to increased efforts by the New York City Department of Education to more accurately identify students’ primary nighttime residence, together these changes highlight a significant trend across the city: rapidly growing child homelessness driven by a rise in families living doubled up.

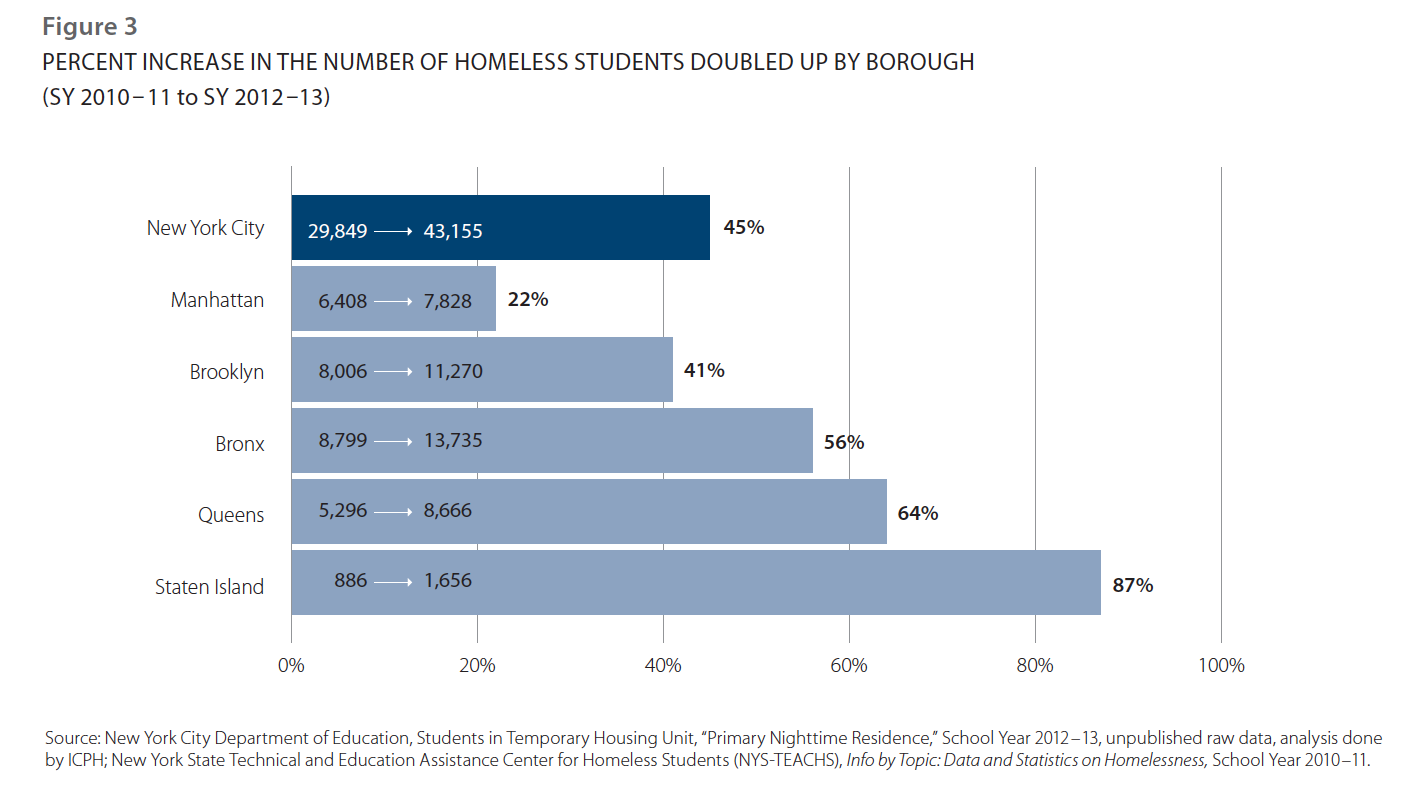

All boroughs saw a rise in the number of doubled-up students between SY 2010 –11 and SY 2012–13; however, a great deal of variation existed in both number and rate of growth across the city. The Bronx saw the greatest increase in the number of students, with an additional 4,936 who were living doubled up attending the borough’s public schools. Staten Island saw the smallest increase in number (770 students), though also the highest rate of growth (87%). Manhattan had the lowest growth rate at 22%. In three out of five boroughs, the total number of homeless students living in doubled-up arrangements grew by more than half, while citywide, the increase was 45% (see Figure 3).

A Doubled-Up Crisis

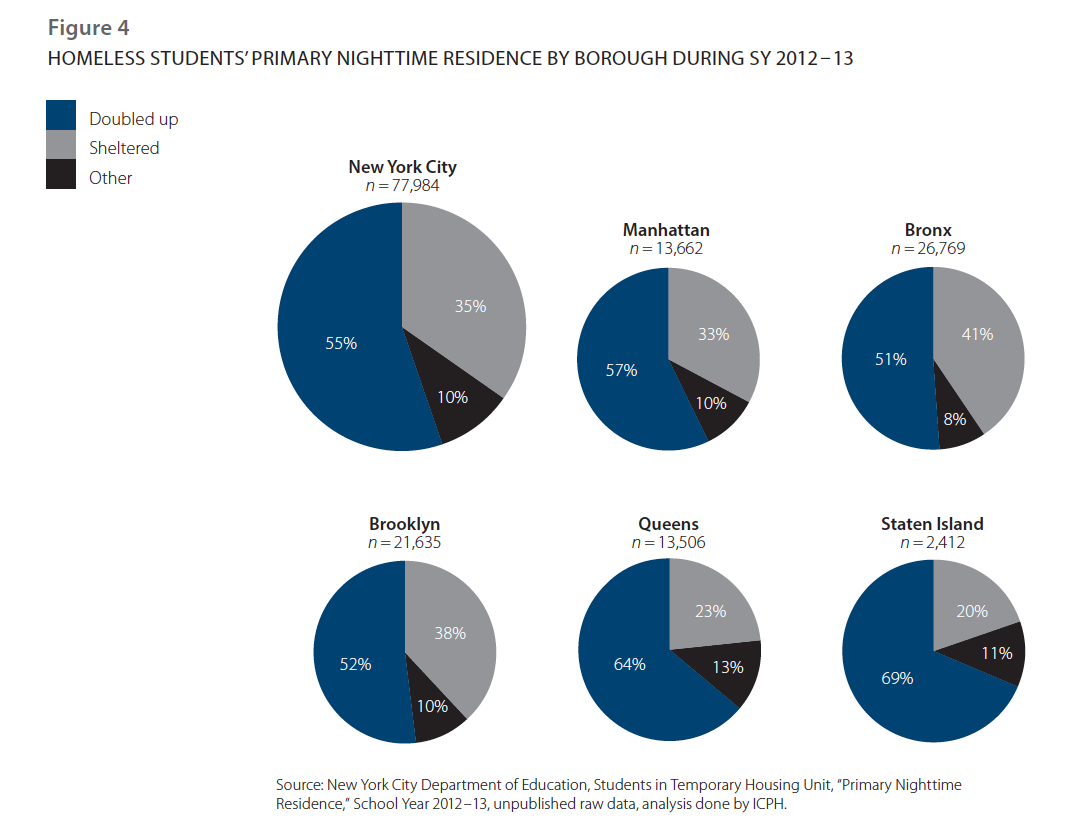

The number of doubled-up students in New York City is not only increasing significantly, these students also represent the largest proportion of homeless children enrolled in public schools. Just over a third (35%) of homeless students resided in shelters during SY 2012–13 and more than half (55%) lived doubled up with family or friends. In the Bronx, Brooklyn, and Manhattan, home to 90% of the city’s 157 family shelters in 2013, the proportion of students living doubled up was 51%, 52%, and 57% respectively. In Queens and Staten Island, boroughs with fewer shelters, the percentage of homeless students living in doubled up arrangements was higher, or 64% and 69% respectively (see Figure 4).4

While all homeless students face educational barriers, students living doubled up may be at even greater risk for instability and its harmful effects on education than their peers living in a family shelter. Compared to the uncertainty inherent in frequent moves and not knowing when a welcome might be overstayed, family shelters (where the average length of stay is well over a year) offer relative stability to homeless children. The rapid rise in doubled-up students may also be a weathervane for the city’s shelter system: the most common living situation prior to entering shelter is unstably doubled up with family or friends.5

Understanding Trends and Meeting the Needs of Homeless Children

The increase in doubled-up students across the city raises a number of questions for policymakers, educators, and advocates. While doubled-up students now make up more than half of all homeless students, little is known beyond the anecdotal about whether or how the needs of these students differ from those of students living in shelter. Education is often the difference between overcoming childhood poverty and succumbing to its effects as an adult. Knowing more about doubled-up students’ educational experiences is a critical step in addressing their needs and mitigating the negative impacts of housing instability.

The dramatic growth of doubled-up students in New York City also has far-reaching implications for the city. More and more families with children are facing homelessness, the most extreme form of poverty, and numbers are much higher than present shelter totals suggest. For every child living in shelter, there are roughly two homeless children who are not in shelter. Given the strong link between those who are homeless living doubled up and reasons for shelter entry, these data suggest that the number of families who are vulnerable and one small crisis away from entering New York City’s family shelters is growing. The increase in the number of doubled-up students is a reminder that the family homelessness crisis in New York City is far from contained and will continue unchecked unless the city looks beyond housing to address the education and employment needs of families struggling with instability.