a policy opinion brief from ICPH

April 2013

A strategy known as “rapid rehousing/housing first” is currently heralded as the answer to reducing family homelessness. The concept is simple: move families immediately from shelter to permanent housing. The problem is thus solved; these families are no longer homeless. In municipalities and counties across the country, rapid rehousing is being implemented and declared an immediate success despite little long-term evidence to support this conclusion. Nowhere has this policy been practiced on such a large scale and for such an extended period of time as in New York City.

This report examines the model of “rapid rehousing/housing first” using New York City as a case study. It specifically examines the impact of this policy on the city’s shelter system for homeless families, focusing on shelter census, eligibility, and recidivism rates, along with length of stay and overall costs.

New York City Shelters

New York City currently houses more than 11,000 families with more than 20,000 children in city shelters.1 In 2005 the city initiated rapid-rehousing policies based on time-limited rental subsidies to foster permanent independent living for homeless families.2 The prediction was that, after a limited period of time, rapidly rehoused families would become financially secure through employment and be able to maintain their living situations independent of temporary rental subsidies. In other words, instances of family homelessness resulted simply from short-term housing crises, and short-term rental subsidies would solve the problem.

For six years, beginning in the 2005 fiscal year and ending in 2011, rapid rehousing was at the heart of New York City’s effort to reduce family homelessness. Over that period some 33,000 families were moved out of shelter.3 During that same period of time, however, the return-to-shelter rate increased significantly, indicating that lack of housing is not the only reason that people become homeless. Based on those numbers and the length of time the program was in place, it is possible to go beyond the qualitative rhetoric currently supporting rapid rehousing and quantitatively define the successes and limitations of this policy.

Shelter Census

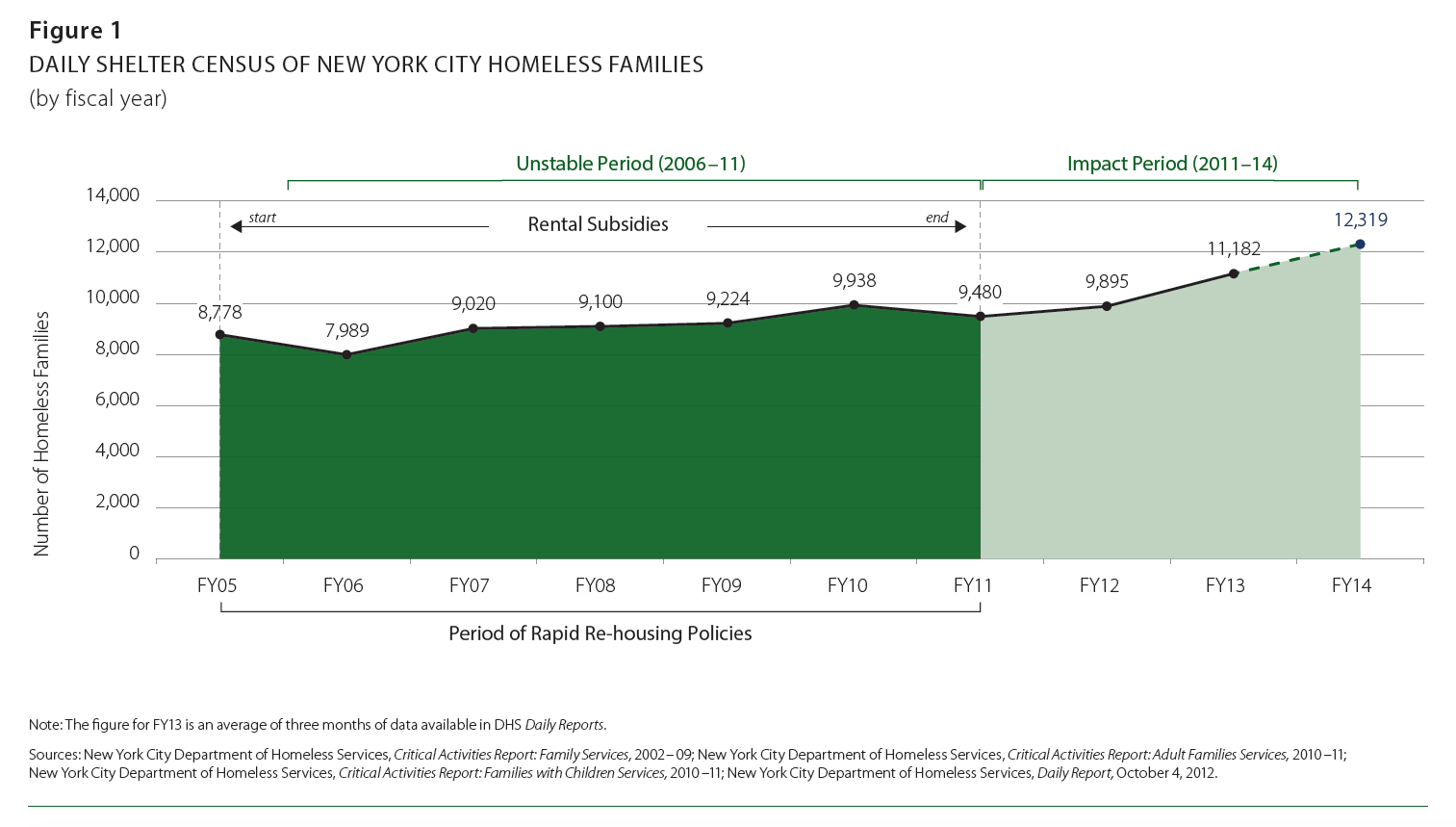

Although designed to reduce family homelessness, rapid-rehousing policies have actually had the opposite effect in New York City. By offering rental subsidies to sheltered families, government actually stimulated homelessness. Numerous families that were living doubled-up or in substandard housing saw an opportunity to secure new housing and entered the shelter system to get places in line. Between FY05 and FY11, when rental subsidies were in effect, the average annual census of families housed in city shelters increased 8%, to 9,480 (see Figure 1).4 Even with the end of rental subsidies, in FY11, the number of homeless families in shelters continued to grow year-over-year:

4.4% in FY12, to 9,895, and 13% in mid-FY13, to 11,182. In all likelihood, families continuing to enter the shelter system are expecting and waiting for a new rehousing initiative to appear. Regardless, if this trend continues, the data projects that there will be more than 12,319 families in shelter by FY14, an additional 10.2% increase.

But why? Beginning here, the unexpected impact of rapid rehousing policies comes into focus.

Shelter Eligibility and Recidivism

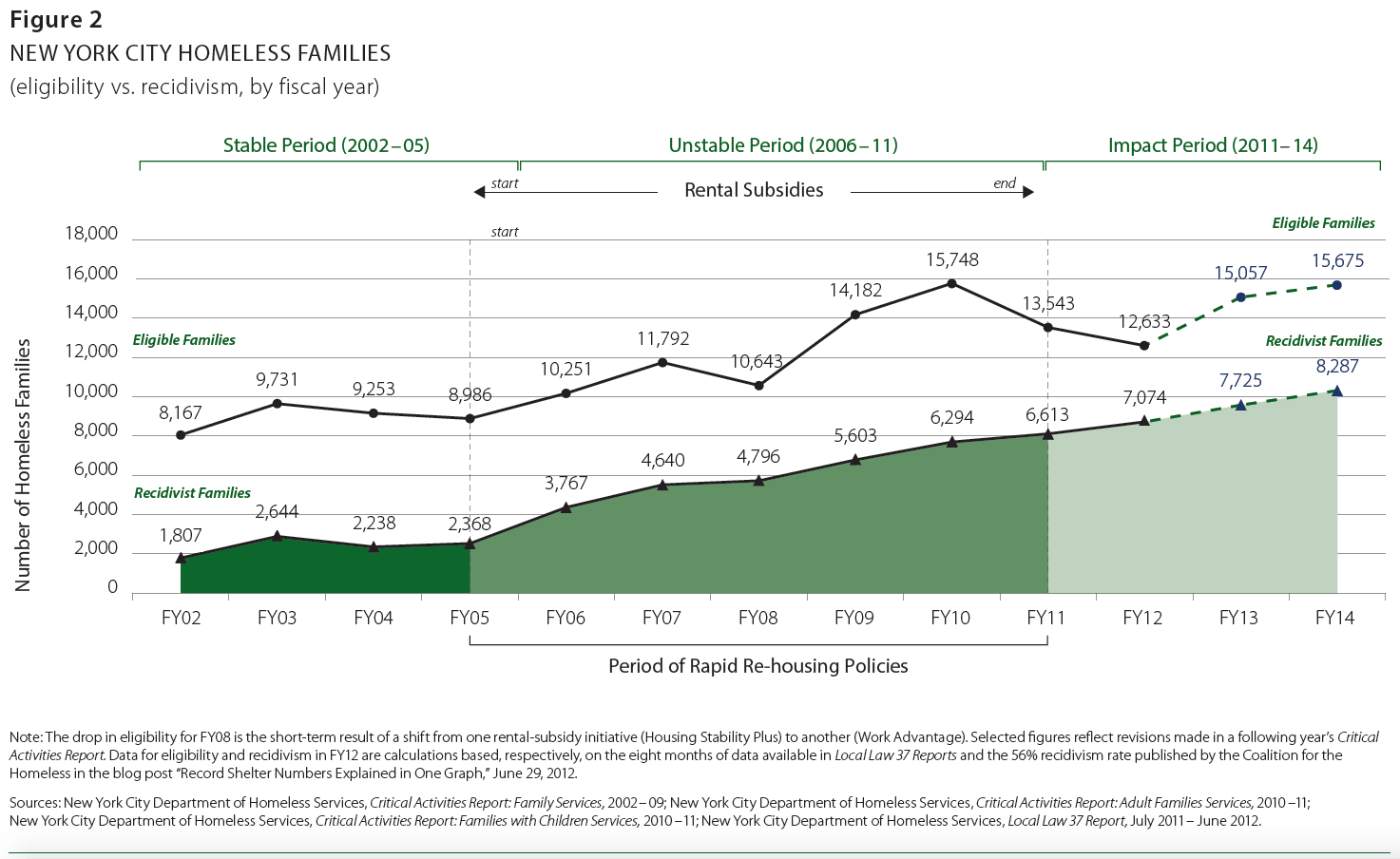

As the average shelter census in New York City was increasing, so too was the rate at which families were undergoing the eligibility-determination process necessary to qualify for shelter. Between FY05 and FY10 the number of eligible families increased 75%, putting more pressure on an already strained shelter system (see Figure 2). This increase revealed a need for shelter that was already present—one that became visible as rapid rehousing initiatives drew more families into the system.

In addition, the recidivism rate, or the rate at which re-housed families return to shelter, saw an upward trend.5 Prior to FY05 and the implementation of rapid-rehousing initiatives (see Figure 2, “Stable Period,” FY02– 05), recidivism in the city’s shelter system remained relatively stable, at a little over 20%. Beginning with rapid-rehousing rental subsidies in FY05, this equilibrium was upset and the system thrown out of balance, resulting in a quick rise in family recidivism (see Figure 2, “Unstable Period,” FY06 –11). Even taking into account other factors that contribute to family homelessness, including the economy and housing costs, this rate of recidivism indicates that families are being moved into housing before they are ready to maintain it.

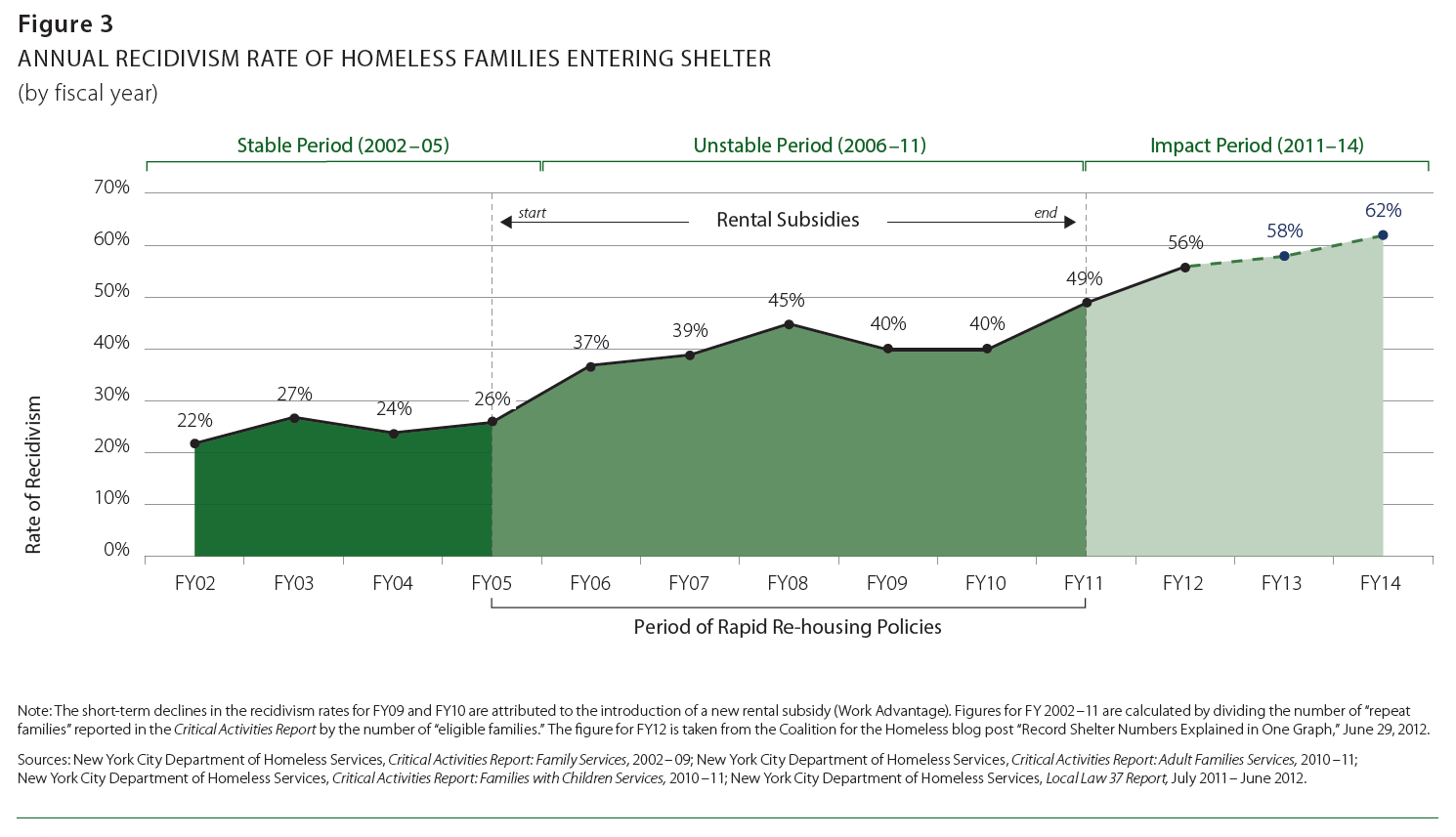

By FY11, when rapid-rehousing rental subsidies were halted, the number of recidivist families had risen an unprecedented 179%, with little sign that it was leveling off. Today, the city’s recidivism rate stands at 56% (see Figure 3).6 Moreover, a longitudinal analysis of recidivism through the “stable” and “unstable” periods of rapid-rehousing initiatives projects recidivism rates of 58% and 62% for FY13 and FY14, respectively (see Figure 3, “Impact Period,” FY11–14).

During the six years when rapid-rehousing policies dominated the city’s strategy for reducing family homelessness, the demand for shelter (whether measured through a daily census or the number of families applying for eligibility) and recidivism rates both increased significantly. These trends are not projected to reverse themselves anytime soon. But that’s not all.

Length of Stay in Shelter

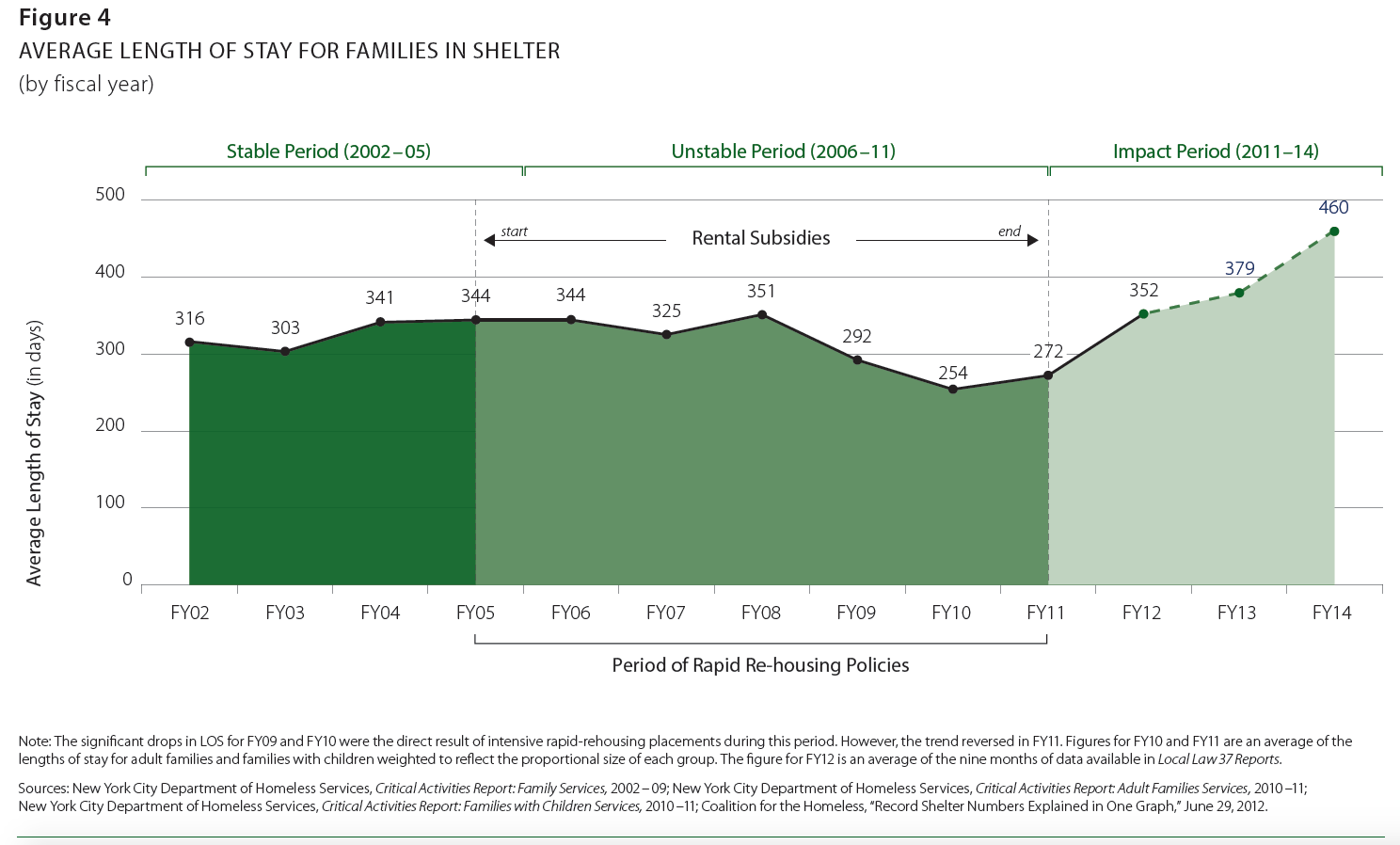

Along with the increases in shelter census, eligibility rates, and recidivism rates, rapid rehousing also greatly affected the length of time families stayed in shelter. In FY12, the year after rapid rehousing was discontinued, the average length of stay (LOS) in shelter rose 29%, to 352 days. In other words, family-shelter stays were lasting 50 weeks, almost an entire year (see Figure 4, “Unstable Period,” FY06–11).7 Projections based on recent trends indicate a 31% increase in LOS by FY14, for an unprecedented 460 days, or 15 months. Once again, rapid rehousing not only increased shelter demand, eligibility, and recidivism, but also length of stay, thereby leading to increased costs. But how much?

xxx

Cost of Shelter

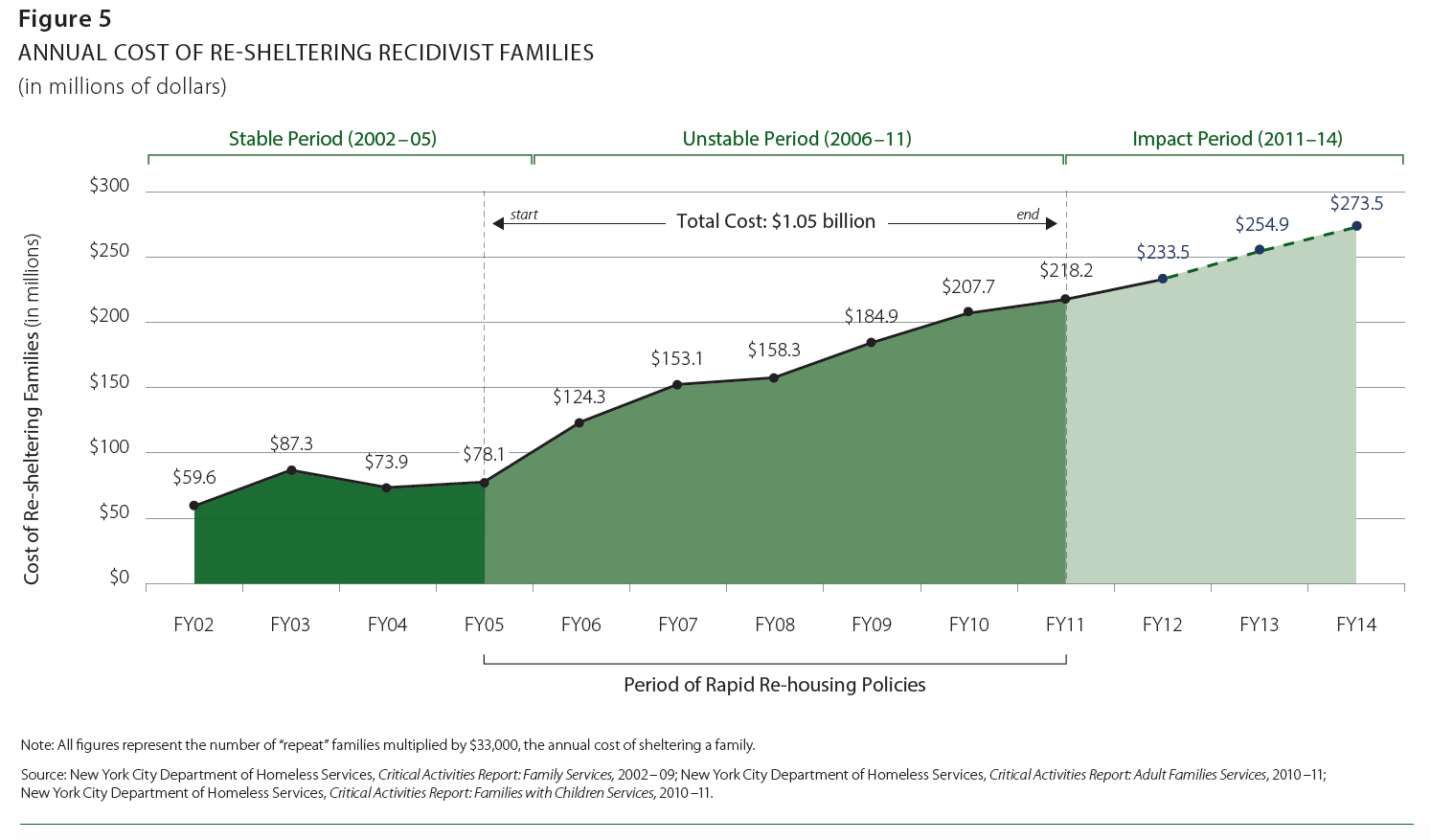

New York City’s adherence to rapid-rehousing policies not only destabilized the shelter system and homeless families; it did so at an unanticipated cost.8 Prior to the shift to rapid rehousing, the average cost of shelter recidivism was approximately $74.7 million annually. Between FY05 and FY11, when rapid rehousing was in full swing, the total cost of returns to shelter was an astonishing $1 billion, an average of $174.4 million per year (see Figure 5). This drastic spike in the cost of re-sheltering families who enter the system multiple times represents a 179% increase over the amount spent prior to the implementation of rapid rehousing policies.

Moreover, the cost of shelter attributed to recidivism continues to rise. It totaled $233.5 million for FY12 and is projected to reach $254.9 million and $273.5 million in FY13 and FY14, respectively. As a consequence, the average estimated annual cost for the current “Impact Period” (FY11–14) is $253.9 million, 46% higher than during the rapid-rehousing period (FY05–11; see Figure 5). This constitutes a true reversal of fortunes for the city.

The Impact

The purpose of this report is not to issue an indictment of New York City; the city government’s task of controlling and reducing family homelessness is a daunting one. Instead, the goal has been to take a critical look at the long-term impact of federally driven rapid-rehousing policies, using New York City as a case study. Ultimately, the rapid-rehousing initiatives of the last decade have, for numerous families, failed to deliver the intended long-term housing stability. In fact, by all accounts examined here, they have failed more than half of these families. This failure raises fundamental questions as to the future effectiveness of this type of policy, widely seen as the key to reducing family homelessness across the country. Rapid rehousing may appear to work in smaller metropolitan and rural localities (only time will tell regarding its continued success), but it clearly has created problems over the long run in a large-scale setting.

As this report demonstrates in the case of New York City, rapid rehousing was analogous to a temporary steroid injected into a stable system, destabilizing city shelters by creating an unnecessary demand, identifying unmet needs through increased eligibility, almost tripling the rate of family recidivism, increasing the average length of shelter stay, and driving up shelter costs. All of this, in turn, created new emergency needs for additional shelter space. Since the end of rapid rehousing in New York City, in May 2012, six new family shelters have opened, with three more in the pipeline for early 2013.9 In fact, New York City was just forced to authorize an additional $43 million for family shelters.10 In essence, rapid rehousing left New York with a costly hangover in the form of an overwhelmed family-shelter system.

The lesson to be drawn from all of this should be clear: “one size fits all” policies for addressing family homelessness do not work.11 Not all families are equal. Some families successfully transitioned to permanent housing after their shelter stays, but others did not. Many have multiple needs beyond simple housing that should be addressed before their move to independent living.12 Rapid rehousing was a failed experiment that produced unwanted incentives and unwarranted costs, all of which the city’s Department of Homeless Services must now address. In New York City, rapid rehousing became a short-term fix for a long-term problem. Whether or not it is successful in the future in other parts of the country, for now the caution light is on.