a policy report from ICPH

June 2016

New York City’s Department of Education spent approximately $3 billion on special education for close to one in five public school students in SY 2013–14.1 Each of these almost 200,000 students had an Individualized Education Program (IEP), a mandated plan outlining the special education services they will receive to support their learning while facing challenges within one of 13 disability categories such as speech/language impairment and learning disabilities.2 Meeting the special education needs of students is critical to their academic success; meeting the special education needs of homeless students, who already face so many challenges, is paramount. While in both policy and practice, students’ needs should be identified as early as possible, homeless students are significantly more likely to receive an IEP later than their housed peers. This report demonstrates the disparity in identifying homeless children for special education and presents data suggesting that late identification has significant impacts on retention, suspension, and academic proficiency. Timely identification and intervention is fundamental to ensure homeless children do not needlessly fall behind in school.*

xxx

Key Findings

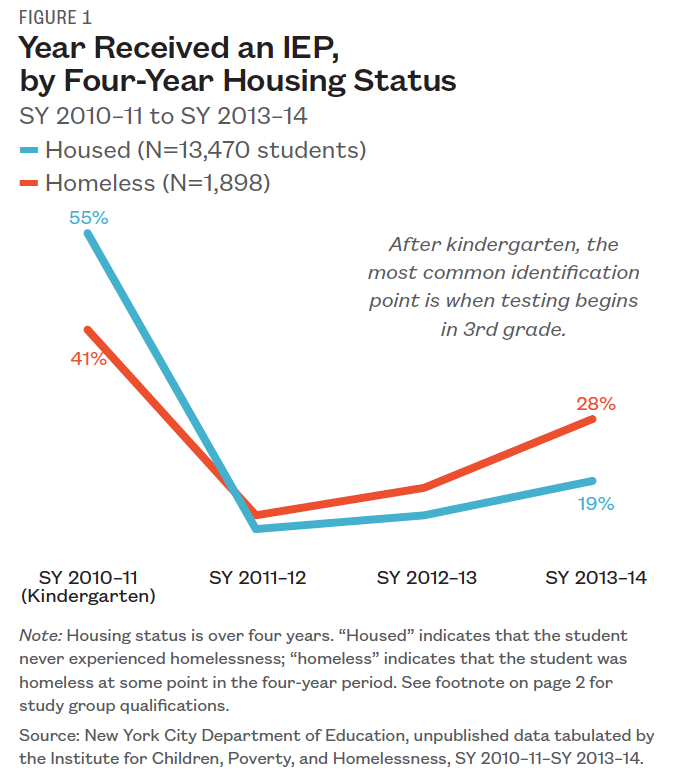

Homeless students with special needs receive IEPs later than housed students. Just 41% of homeless students with special education needs had an IEP by the end of Kindergarten, compared to 55% of housed students.

Homeless students who receive IEPs early are more likely to remain with their age and grade-level peers and to achieve grade proficiency. Homeless students who had IEPs by the end of Kindergarten were held back at half the rate of those who received IEPs later. They were also twice as likely to score proficient on 3rd-grade State assessments (17% compared to 9%).

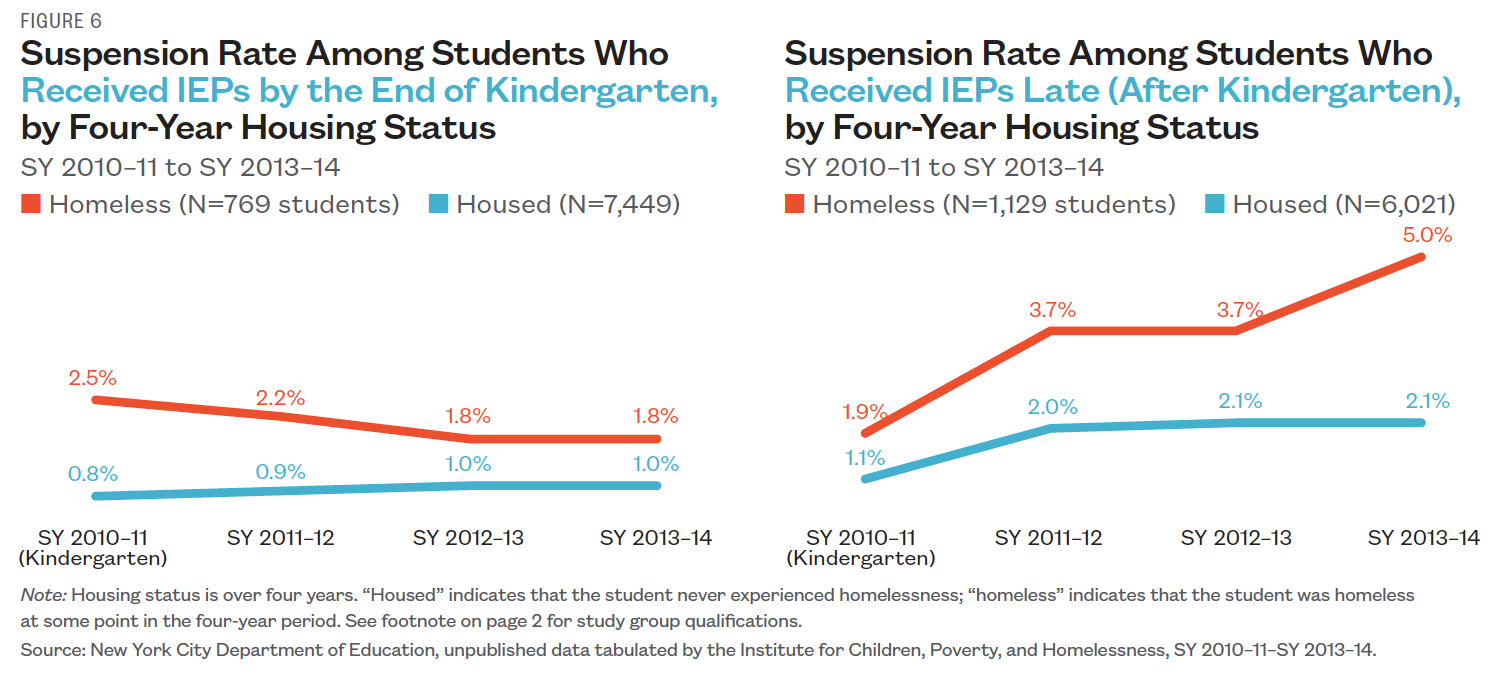

Homeless special needs students who receive IEPs early are suspended less. Less than two percent were suspended in their 3rd-grade year, compared to five percent who received their IEP after Kindergarten.

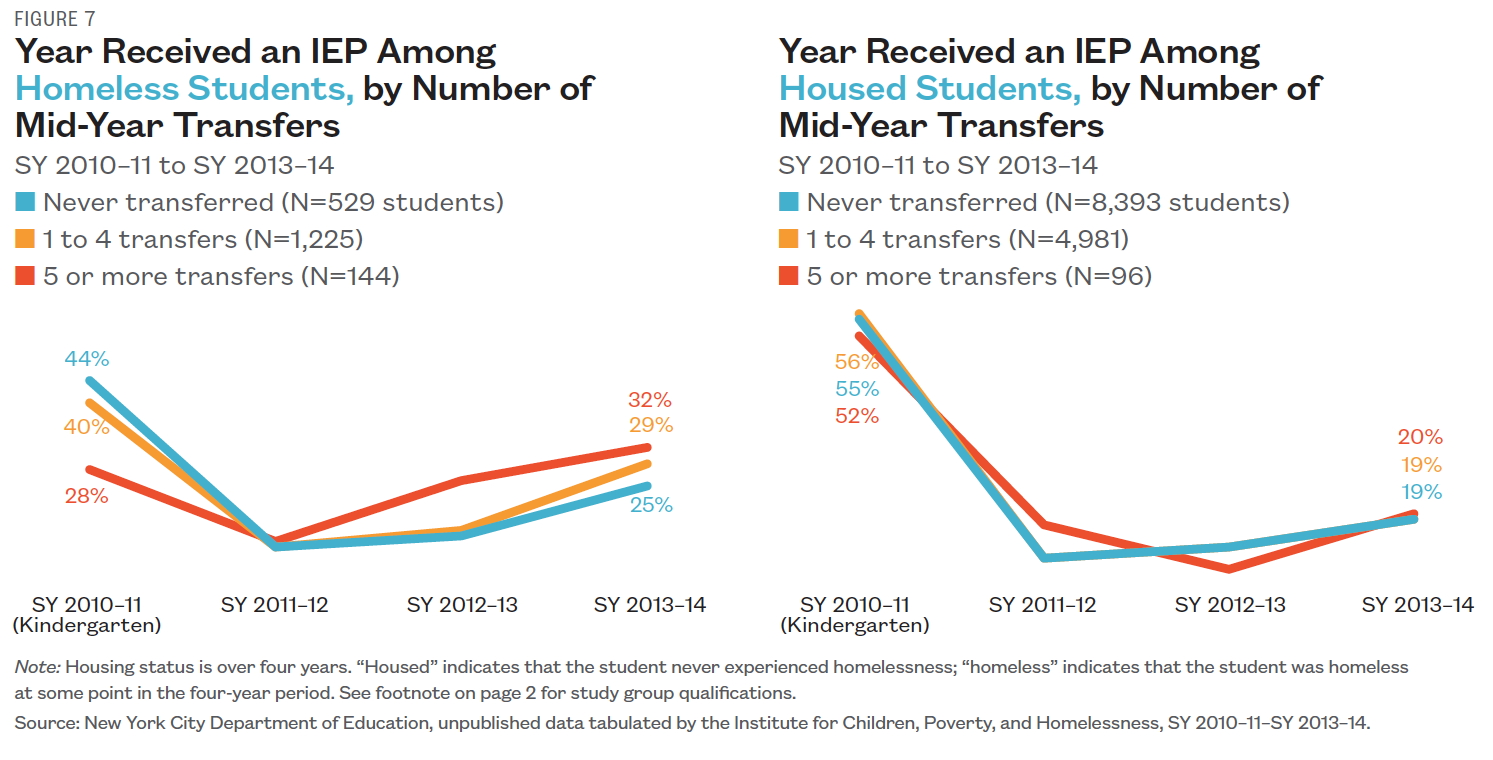

School stability helps homeless special needs students connect with IEP services earlier. Close to half (44%) of homeless students who remained in the same school each full school year received IEPs by the end of Kindergarten, compared to less than 1 in 3 (28%) homeless students who transferred more than once per year on average.

xxx

What Are Individualized Education Programs (IEPs)?

Every child with a disability has the right to a free appropriate public education supported by necessary special education services, and districts are legally required under the Child Find law to identify and evaluate all children with disabilities. The IEP is the mandated document outlining the specific individual supports and services that the child will receive, created through a team process involving parents, teachers, administrators, and others.3

*The data presented in this report looks at a group of 15,368 students who met the following qualifications: (1) enrolled in Kindergarten in SY 2010–11, (2) of eligible age to enter Kindergarten for the first time that year (turned age 5 between January 1, 2010 and December 31, 2010), (3) enrolled in a New York City Department of Education (NYC DOE) public, non-charter school for all four years between SY 2010–11 and SY 2013–14, and (4) received an IEP at some point over the four-year period. Receiving IEP services and being identified for an IEP both refer to the point in time at which the student first had an active IEP in the NYC DOE computer system.

xxx

Later Identification of Special Needs

Only 41% of homeless special needs students had IEPs by the end of Kindergarten, compared to 55% of housed students (Figure 1). Not only were homeless students less likely to have an IEP in Kindergarten, but they were also more likely to get their IEP in third grade, considered quite late by any measure.

xxx

Over 31,000 students with special education needs experienced housing instability between SY 2010–11 and SY 2013–14.4 These students face many challenges, and key among these is the early identification and receipt of services to meet their individual educational needs. The federal Individual with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) requires each state to establish “child find” regulations as to how schools will identify all children, including those who are highly mobile such as homeless children, as children with disabilities.5 In New York City, school districts must refer students for evaluation when educators notice anyone failing to make adequate progress in regular classroom instruction.6 Nonetheless, homeless special needs students were less likely to receive timely IEPs than their housed peers—only 41% of homeless special needs students had IEPs by the end of Kindergarten, compared to 55% of housed students (Figure 1). Not only were homeless students less likely to have an IEP in Kindergarten, but they were also more likely to get their IEP in third grade, considered quite late by any measure. In virtually every City school district where data was available, the majority of homeless special needs students received their IEP in their 1st-grade year or later. The same was true for housed students in only eight (or 30%) of those 27 districts.7

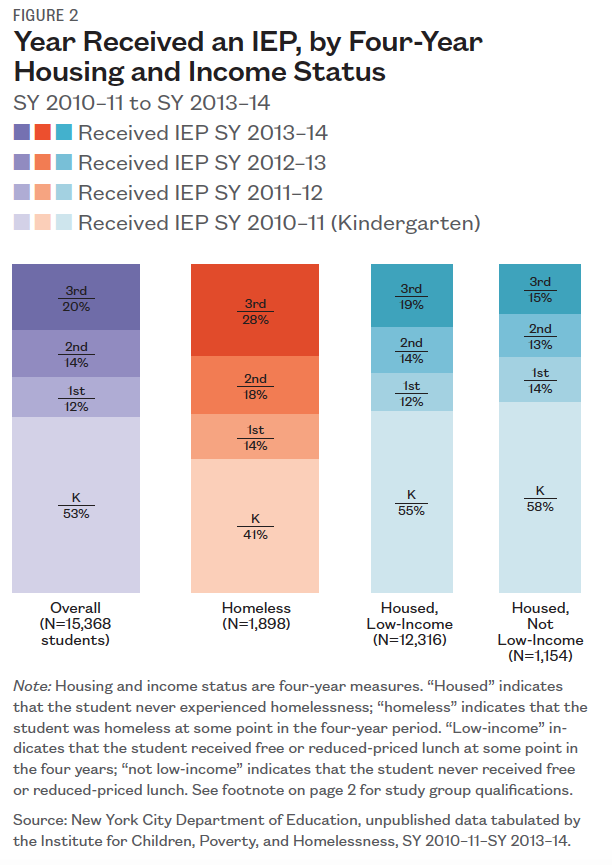

This inequality exists beyond the poverty and resource-stretched schools that are so often blamed when explaining why children are underserved. As shown in Figure 2, more than one in every four (28%) homeless students did not receive an IEP until their 3rd-grade year (SY 2013–14) compared to 19% of low-income housed students—highlighting the unique struggles and educational consequences of housing instability. For too many young homeless students, this meant going without the educational supports needed to succeed for the first three years of school.

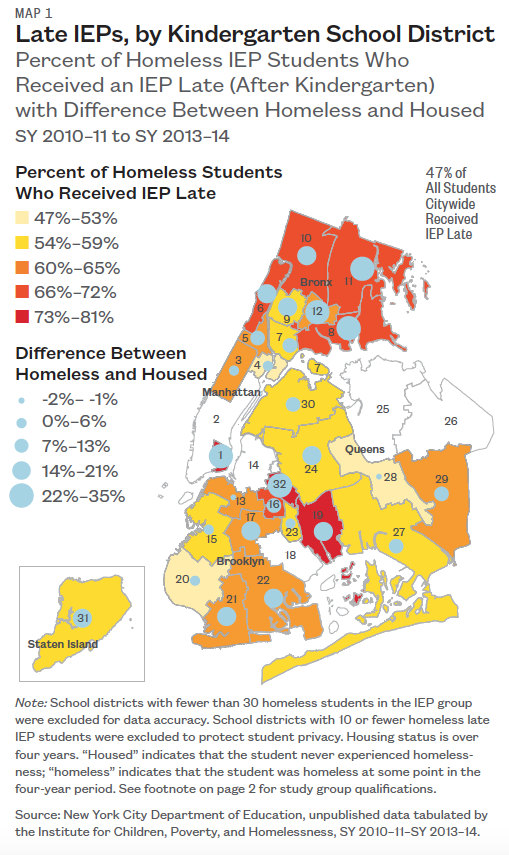

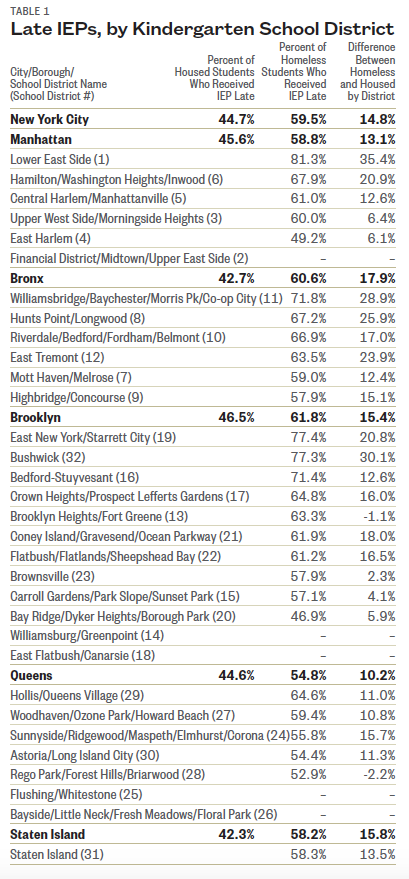

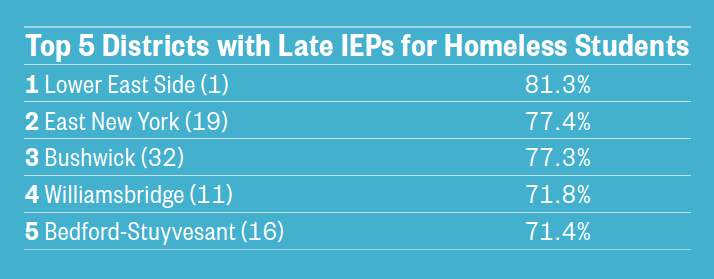

New York City’s school districts vary in their support of homeless students’ disability needs. As shown in Map 1, the percentage of homeless special needs students that received IEPs after Kindergarten ranged from 47% in School District 20 in Brooklyn to a staggering 81% in Manhattan’s District 1. School District 1 also saw the greatest disparity by housing status: while housed students were roughly following the citywide average trend, the proportion of homeless students who received IEPs after Kindergarten was 35 percentage points higher. Meanwhile, School Districts 13 and 23 in Brooklyn and Queens District 28 identified homeless and housed students at the same rates (±2%). These differences highlight important opportunities for improvement and learning across districts.

xxx

Timing of Services Matters

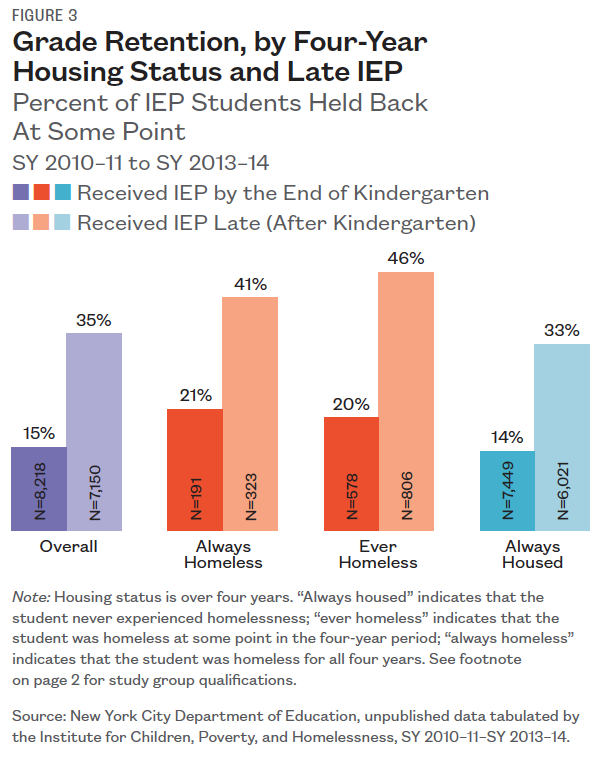

Close to half (46%) of ever-homeless students were held back at some point if they did not receive IEP services by the end of Kindergarten, compared to 33% of those who were always housed.

Grade promotion setbacks

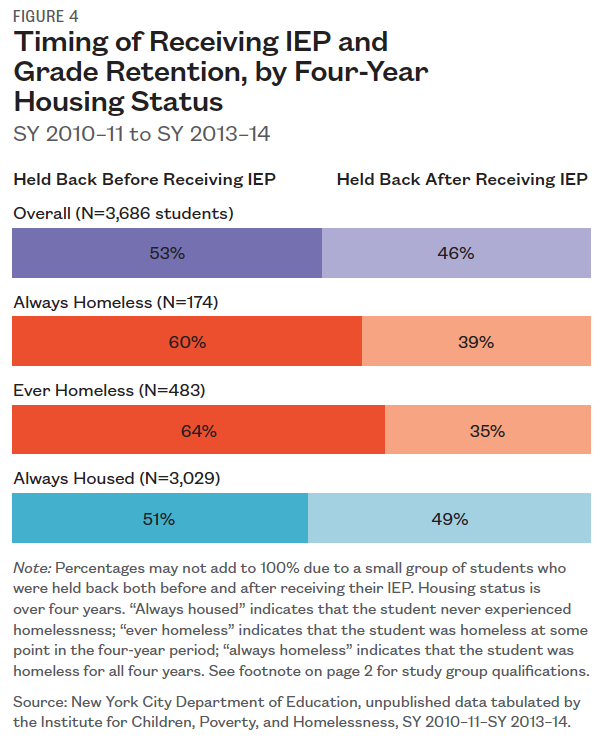

For those homeless children who received their IEPs early, the effect was dramatic. These students were more likely to remain with their age and grade-level peers over time. Homeless students with IEPs in Kindergarten were held back half as often as those who got their IEP later (Figure 3). This was also true for housed students with early IEPs—early identification is important for all students. However, the impact of timely identification on homeless students remains even greater. Close to half (46%) of ever-homeless students were held back at some point if they did not receive IEP services by the end of Kindergarten, compared to 33% of those who were always housed. Furthermore, Figure 4 shows that among homeless special needs students who were retained at some point, the majority received their IEP after they had already been held back a grade. This timing suggests a missed opportunity to support those young students before they must repeat a grade. Moreover, it is likely that behavioral problems and other issues contributing to the retention of these students are linked to the failure to properly identify and serve these students. While this is precisely what the “child find” requirements of IDEA are designed to prevent, far too many homeless students are slipping through the cracks.

Timing can matter even more for certain types of disabilities. For instance, one in three IEPs (31%) issued last year in NYC focused on speech or language impairments—needs that, if identified at the beginning of a child’s education, can be addressed before the student experiences the educational consequences of falling behind.8 For homeless students, these consequences further compound the emotional trauma and other challenges they already face.

xxx

Academic setbacks

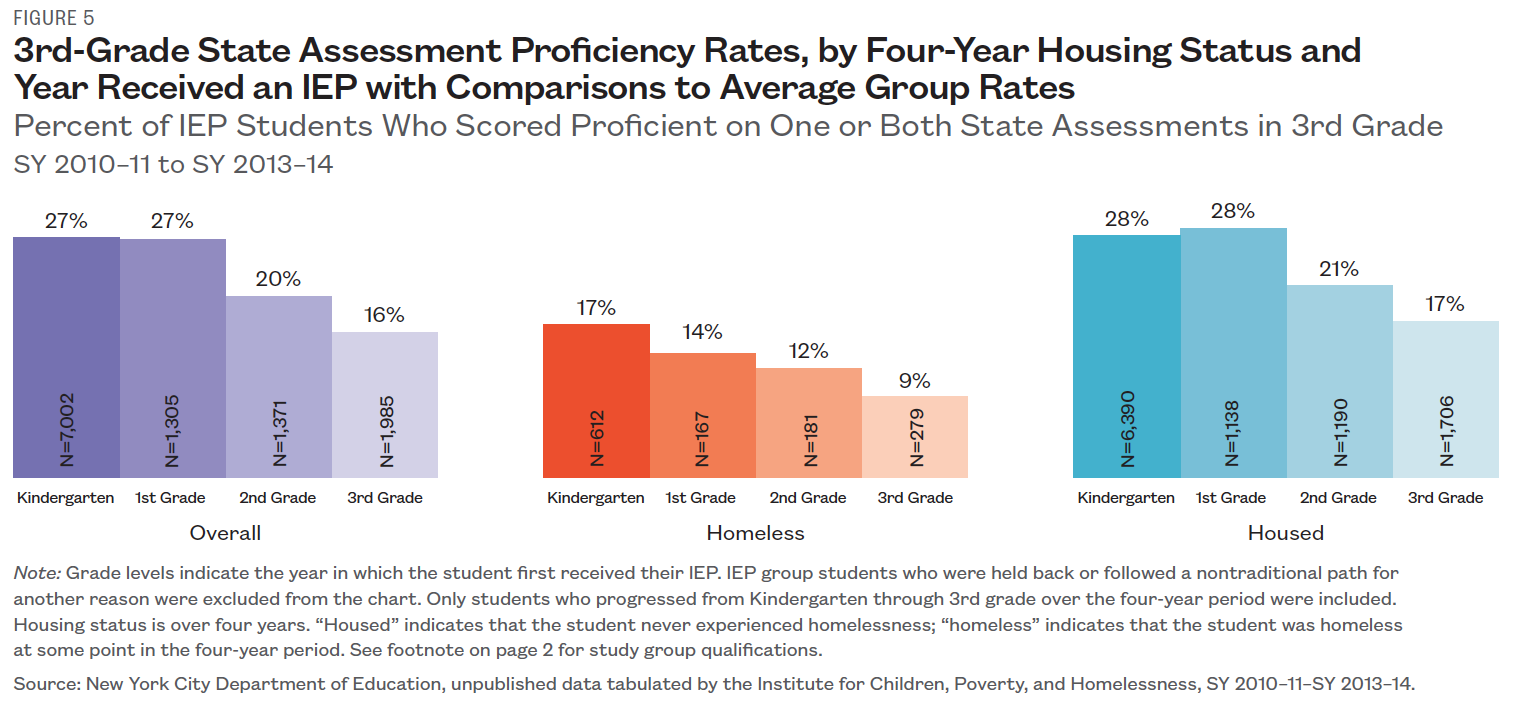

Examining State assessment scores provides another useful benchmark for understanding why early IEP intervention is critical. While proficiency rates for all IEP students were far lower than for the overall student body, homeless students who had an IEP by the end of Kindergarten were more likely to be grade proficient by 3rd grade. These students scored proficient on State assessments at roughly twice the rate of homeless students who did not receive an IEP until 3rd grade (Figure 5). This doubling of the proficiency rate highlights the potential impact of early IEP identification for students during these early years when they are gaining skills and knowledge crucial to academic achievement for the rest of their lives. Without the appropriate supports, these students are needlessly prevented from learning all they could in these years, the effects of which may ripple into their middle, high school, and even college education.

Behavioral setbacks

Children with special needs face social and behavioral challenges as well as academic. Overall, New York City public school students with IEPs experience more suspensions than their peers: 2.1% of 3rd-grade special needs students were suspended in SY 2013–14, three times the rate of those without IEPs (0.7%). Homeless students saw an even wider disparity: 3rd graders with IEPs were suspended four times as often as non-IEP students (4.3% compared to 1.3%). While this gap is troubling, Figure 6 shows that early intervention helped for homeless special needs students: just 1.8% of those who had an IEP by the end of Kindergarten were suspended in their 3rd-grade year (SY 2013–14). Meanwhile, homeless students who received their IEP later saw an increasingly higher likelihood of being suspended each year. By those students’ 3rd-grade year, 1 in every 20 was suspended (5.0%). Outlining children’s support needs in IEPs during early developmental years is critical to help school administrators and teachers prescribe appropriate behavioral solutions that benefit homeless children’s progress and keep them in school.

xxx

School Stability Matters

Housing instability undermines school stability, with one out of every four homeless students transferring schools at least once during SY 2013–14, compared to fewer than one in ten housed students.9 Discrepancies are found in special education identification as well: homeless special needs students who spent each full year in the same school had a better chance of receiving an IEP early. As shown in Figure 7, 44% of homeless students who never transferred mid-year received IEPs by the end of Kindergarten compared to only 28% of those who experienced high levels of school instability—transferring mid-year more than four times over the four-year period. Among those who transferred more than once per year on average, students were most likely to receive an IEP in their 3rd-grade year (32%). With all homeless students far more likely to experience this level of school turnover, we must ensure that special needs children who transfer schools due to housing instability receive the same attention and supports as their peers.10

xxx

Resolving the Disparity

Addressing the disparity in the receipt of special education services for homeless students will require multi-faceted solutions, from programs that strengthen school engagement to an emphasis on early screening and evaluations. Helping young students remain in the same school for the full year and connecting them to additional programs, whether after-school services, English language learning programs, or others, can ensure that children who have special education needs are not overlooked. Schools are not the only place where students can receive support, however; staff at shelters or other public agencies can also request that homeless children be evaluated for an IEP or connect them to services before they even enter school.11 These additional supports and others can ensure that special education needs do not impede the educational path of the already-marginalized group of children whose families struggle with housing instability.

xxx