a policy spotlight

February 2017

The preschool years are crucial to a child’s physical, intellectual, and socio-emotional development. They also represent a window of opportunity for identifying developmental delays that may negatively affect a child’s education if left unaddressed. Early identification of special education needs improves long-term educational and social outcomes for children and is mandated under the federal Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA).1,2 It has also been shown to decrease economic burdens through improving academic success and reducing the need for special education as children age.

The Committee for Preschool Special Education (CPSE) in New York City is charged with providing special education services to eligible children ages three to five.3 While all preschool-age children in NYC should have equal access to special education supports, children who are homeless are dramatically underrepresented in the CPSE program. This leaves young homeless students more vulnerable to falling behind their peers socially and academically when they enter elementary school and can have long-lasting educational impacts. This report looks at Preschool Special Education program enrollment data and finds that more efforts are needed to identify and reach homeless children ages three to five who have special education needs. New York City’s family shelter system—including its single point of entry, PATH4—could be utilized to increase the identification of homeless children in need of special education services.

Underrepresentation of Homeless Children Ages 3 to 5 in Special Education

Experiencing homelessness at a young age negatively impacts early childhood development. Lack of safe places to crawl and play as a toddler can delay fine and gross motor skill development, and the trauma of homelessness can affect speech and social skill acquisition. The instability and unique challenges faced by homeless children put them at a greater risk for experiencing developmental delays and early identification of special education needs is crucial. Homeless students, however, are dramatically underrepresented in NYC’s Preschool Special Education program.

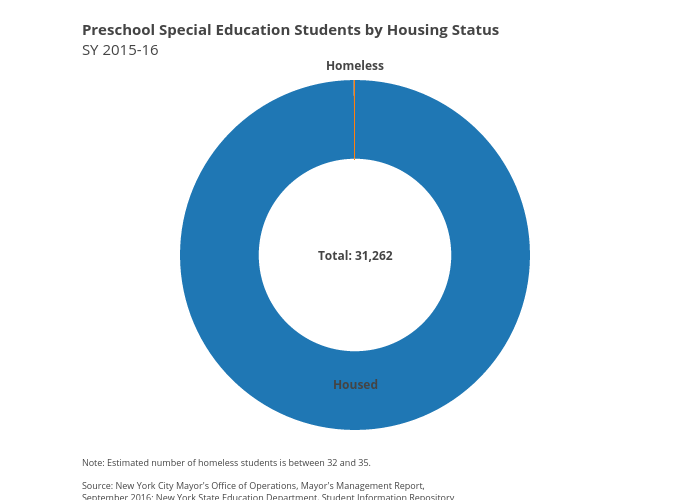

Only 35 out of the 31,262 children enrolled in Preschool Special Education were homeless (0.11%). This is much lower than the citywide rate of student homelessness (8%).5

Magnitude of the Problem

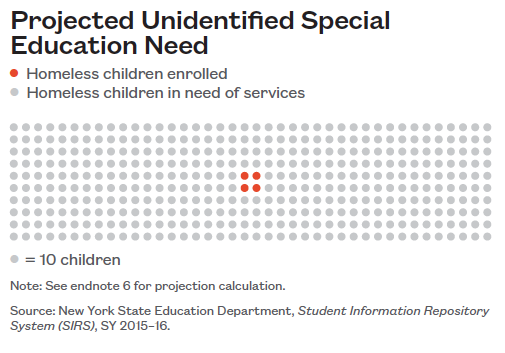

With an estimated 20,000 homeless three- and four-year-olds citywide, there are likely over 4,000 homeless children in need of services through the NYC Preschool Special Education program who are not being reached.7

The Unrealized Impact of Universal Pre-K on Special Education Services for Homeless Students

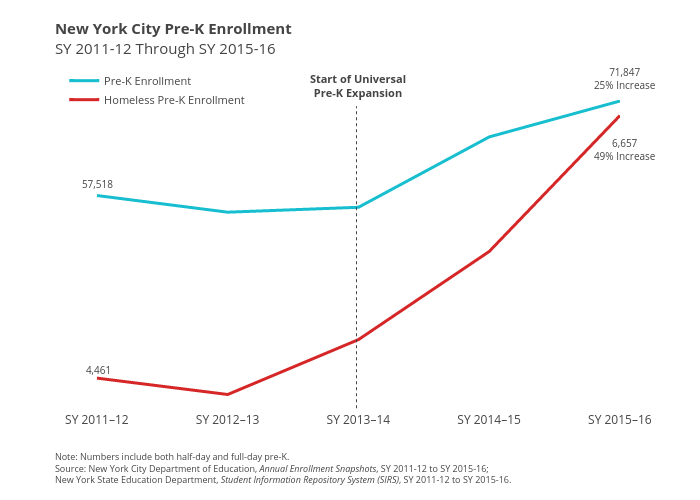

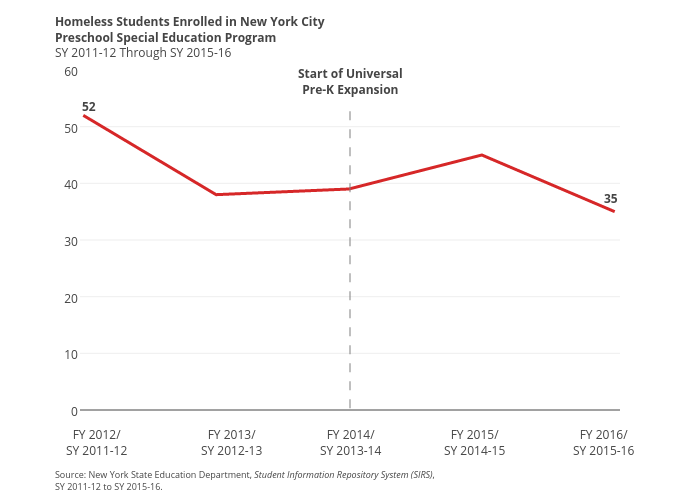

All children who turn four by December 31 are now eligible for New York City’s Universal pre-K program. With the expansion of the program beginning in SY 2013–14 enabling more homeless children to participate in preschool, it would be expected that the number of homeless children identified for Preschool Special Education would increase. That, however, has not been the case.

Pre-K enrollment increased by 25% from SY 2011–12 to SY 2015–16. Enrollment of homeless pre-K students increased by 49% in the same time period.

During this same time overall enrollment in the City’s Preschool Special Education program increased by 13%, yet enrollment of homeless students in the Preschool Special Education program declined by 33%.

Decline in Preschool Special Education forHomeless Children Despite Overall Pre-K Growth Policy Considerations

Policy Considerations

There is a need for greater recognition of the special education needs of homeless preschoolers. An estimated 20,000 homeless three- and four-year olds live in New York City and it is likely that at least 4,000 of these children have special education needs that are not being met.

If allocated, additional resources for existing City agencies, such as the Administration for Children’s Services (ACS), the Department of Homeless Services (DHS), and the Department of Education (DOE), as well as community-based social service organizations could be leveraged to increase identification for this vulnerable group of children.

The family shelter system could assign dedicated staff to both identify and help parents complete the Preschool Special Education program evaluation— a process that can often be difficult to navigate. These services could be provided to both parents living in the shelter and families living in the surrounding community, transforming shelters into community residential resource centers.

Universal developmental screenings could be implemented at PATH—the City’s central entry point for the family shelter system—for homeless children under the age of five whose families apply for shelter.

PATH could serve as an informational resource for homeless parents to raise awareness about the free Preschool Special Education services that are available through the City and how, if needed, they can be vital to healthy child development and school success.

Schools could provide developmental screenings for younger siblings of homeless students identified as living doubled up. This could help to reach homeless children who are the most likely to be disconnected from City agencies.

Early identification of children for special education services has been shown to decrease economic burden through improving academic success and reducing the need for special education as children age. In other words, it is not only the right thing to do but it will save the city much needed dollars in the long run. Reaching homeless preschoolers requires some effort and up-front cost. This investment, however, will pay off with savings from the additional services that older children identified with special needs will otherwise require. Doing nothing will be costly in the long term and will negatively impact the education of thousands of children.

While experts agree that this report provides accurate analysis of available data, they also raise the question of whether children served under preschool special education are not properly identified as homeless. Data collection requirements, along with special education funding and policy priorities, have not considered the size of the homeless preschool population, nor the magnitude and cost of the challenges they face.

Establishing clear reporting protocols could better target government funding so that children would get the earliest opportunity to level the educational playing field; moreover, taxpayers would avoid greater expense to the public coffers as the unmet needs of these children cause them to fall further behind.