By Caroline Iosso, Senior Policy Associate, HFH and Max Rein, Policy Assistant, HFH

Introduction

At the close of FY22, there were 9,181 families with children living in Department of Homeless Services (DHS)-run shelters in New York City.1 What brings families to shelter varies, from loss of income to eviction, from domestic violence to seeking asylum in the United States. No matter the precipitating factor(s), every family who seeks shelter in New York City follows the same basic process to be deemed eligible for shelter by DHS.

A family seeking shelter must apply for it at the Prevention Assistance and Temporary Housing (PATH) intake center in the Bronx. Intake may involve several hours of waiting, and several hours of speaking with PATH employees and filling out forms. Families are required to share where they lived for the previous two years and provide proof of each address. After these interviews, families receive a “conditional placement” at one of the City’s shelters. There, they will wait for DHS investigators to determine whether they are eligible for shelter. Each eligibility determination is supposed to happen within 10 days, theoretically giving investigators 10 days to reach out to the client’s contacts, verify their two-year housing history, and confirm that they have no viable housing options. For many clients, this process is inefficient, lengthy, and takes a significant toll on their emotional and socioeconomic well-being. Clients can repeatedly be found ineligible for over a year.

The following report will detail both the inefficiencies in the process of determining eligibility as it stands and the damaging effects of the continual denial of eligibility on families and on shelter staff. As many organizations and elected officials have previously reported,2,3,4 the process is harmful and rooted in a fundamental mistrust of families experiencing homelessness; the two-year housing history and investigations by PATH employees are, in part, meant to determine who is “gaming the system.” Regardless of whatever proportion of families do have viable housing options other than shelter, it is clear from this research that PATH’s eligibility process forcefully discourages all homeless families who are in need of services and housing. This report seeks to continue the public discussion5,6,7 of the eligibility process’ flaws, share the real-life consequences of these flaws, and highlight opportunities for reform.

Note: Citations and sources for data are included in the PDF version of this document available by clicking Downloads underneath the Table of Contents.

A Background on Shelter Eligibility

After the landmark case Callahan v. Carey granted a right to shelter for all single men in New York City, litigation to determine whether this right extended to single women and to families with children soon followed. In 1983, the Legal Aid Society filed McCain v. Koch to determine whether homeless families with children could be entitled to emergency shelter. In 1986, a preliminary ruling was issued that barred the denial of emergency shelter to homeless families, though the lawsuit wouldn’t be settled and an official decision issued until 2008. In the interim, the policies surrounding eligibility for shelter have been negotiated and renegotiated by mayoral administrations. In 1993, the Dinkins administration responded to continuous growth in the shelter population by creating eligibility standards for shelter. In 1996, the Giuliani administration tightened these standards significantly, shifting the model to one of investigation rather than assessment. This change led to a 15% decrease in the family shelter census between 1996 and 1998.8 In 2004, the eligibility process changed again, as the Bloomberg administration introduced preventative supports and assessment as part of the intake process for families. New York State’s Office of Temporary and Disability Assistance (OTDA) loosened eligibility requirements in 2015 through a rule change, which led to many more needy families being found eligible on their first application. The rule was suddenly reversed, however, in 2016, closing the front door to services once again.9 Throughout the years, these changing standards have not necessarily quelled the need for shelter but have instead reflected the attitudes of mayoral and gubernatorial administrations10 regarding the importance of driving down the shelter census at certain times.

The current New York City administration under Mayor Eric Adams has indicated a desire to retrain the Department of Social Services’ workforce in customer service; the Department’s Commissioner Gary Jenkins recently noted in a forum hosted by New York Law School that historically their charge has been narrowly focused on determining eligibility.11 This shift in modality may address some of the issues outlined in the forthcoming sections.

Note: Citations and sources for data are included in the PDF version of this document available by clicking Downloads underneath the Table of Contents.

Conditionality at HFH and in NYC Shelters

In order to assess the scope of the issue of families trapped in conditional status, ICPH worked with the four family shelters operated by its sister organization, Homes for the Homeless (HFH), to interview families and shelter staff and to analyze data. All families who participated in interviews did so voluntarily, and the data and opinions included here are de-identified. This section is an examination of the nature of conditionality at HFH shelters and an analysis of the information that DHS releases on applicants for shelter citywide.

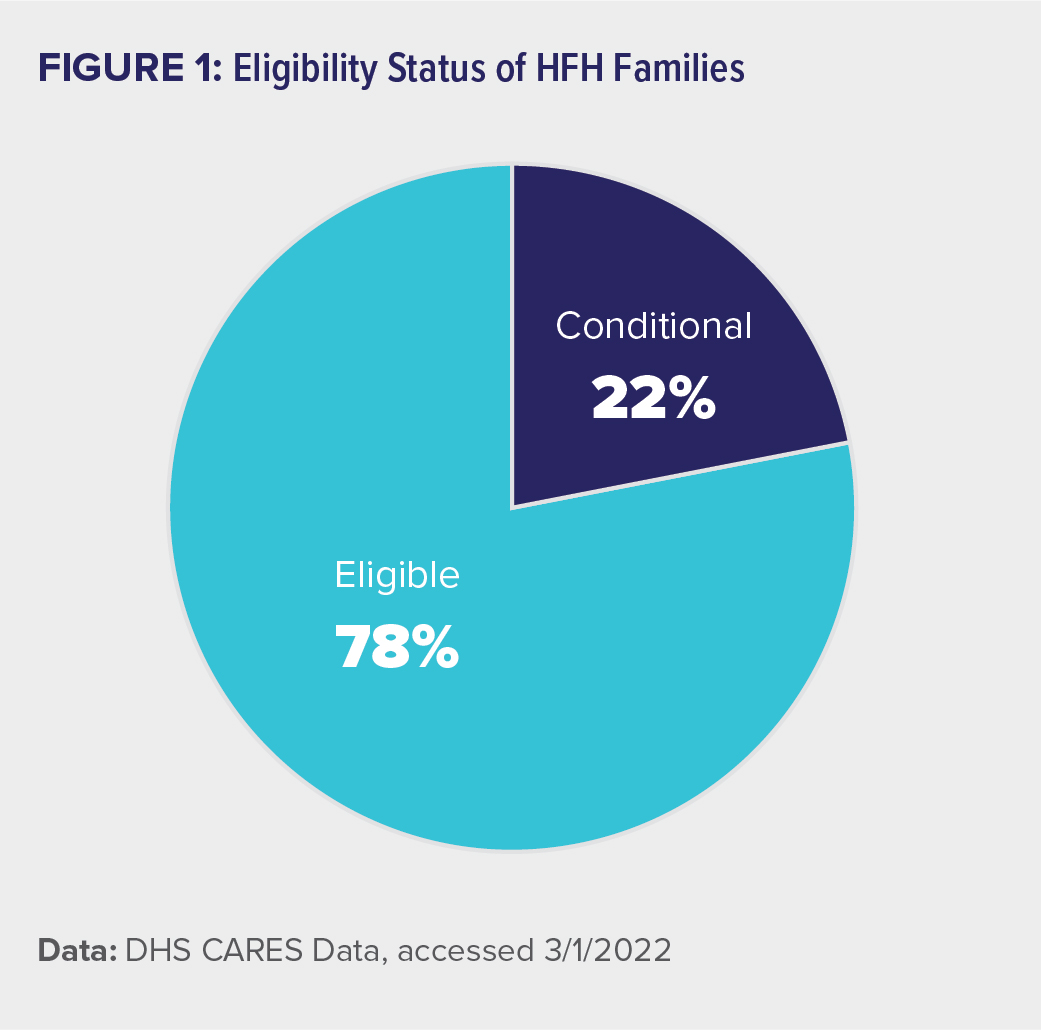

Nearly one fourth of families staying in HFH shelters are in conditional status.12,13

While the process for determining shelter eligibility is supposed to take 10 days, only 15% of families are deemed eligible in this time frame. Often, families will wait weeks before finding out whether they are eligible for shelter or not. This, in combination with having to reapply for shelter eligibility repeatedly, leads to many families being in conditional status for far longer than the 10-day period. Almost the same number of families are conditional for over 150 days as the amount who are found eligible in fewer than 10 days. The median length of time spent in conditional status for HFH clients is almost 40 days.

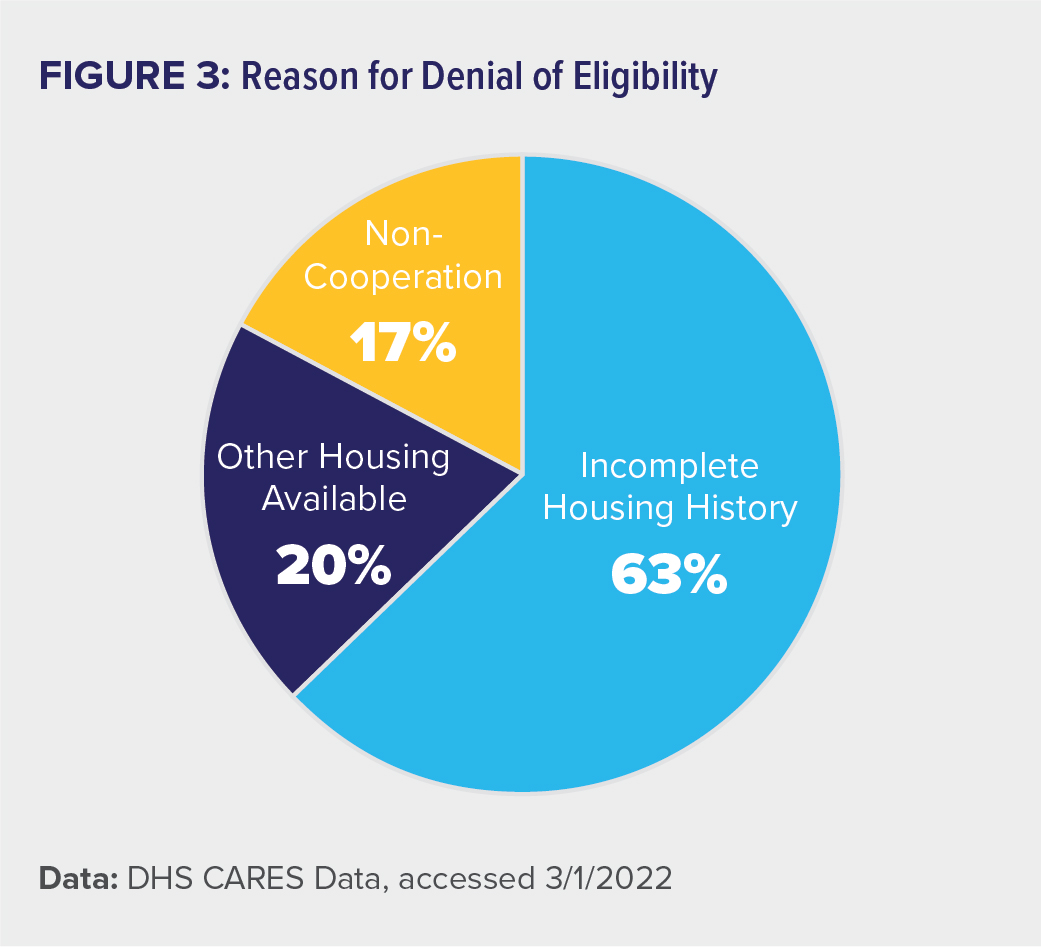

Families are most frequently found ineligible for shelter for one of three reasons, as seen in Figure 3 below.14 For the largest proportion of clients, DHS determines that a family has provided “incomplete housing history.” The family applying for shelter must provide DHS with their past two years’ of housing history. Missing even a single day in those two years or not providing what the DHS staff member determines is a valid form of proof is enough to lead to a determination of ineligible.

Many families are deemed ineligible when DHS believes that they have “other housing available.” DHS will issue this determination if they feel that a family has left a residential situation that could still be viable. Often, DHS will suggest a living situation that the family does not feel is tenable, such as an overcrowded apartment or shared quarters with an individual with whom they are in constant discord.

Clients may also be deemed ineligible due to “non-cooperation.” This notice is given to families when they miss a meeting they are supposed to attend or do not call PATH when they are supposed to.

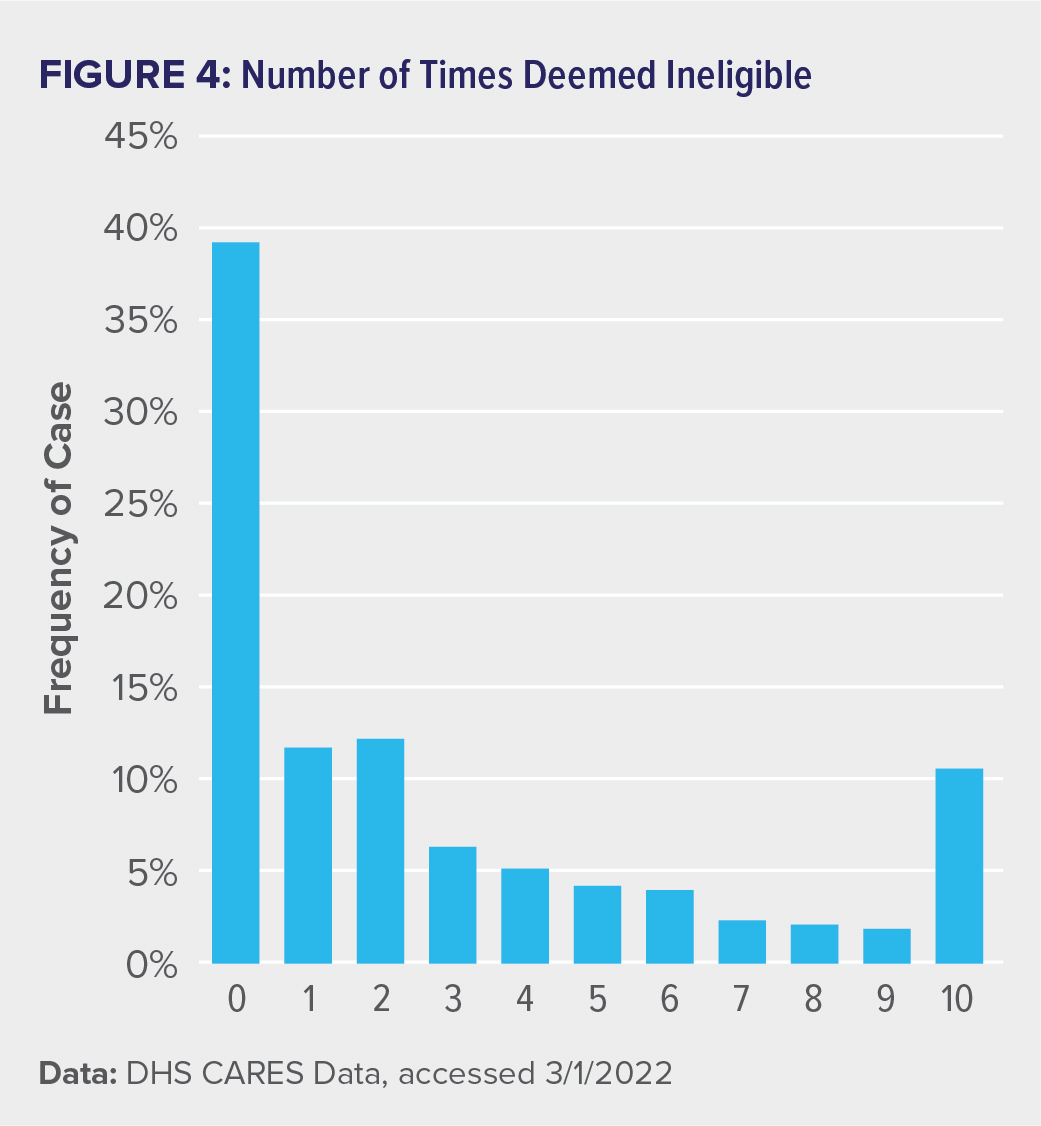

In Figure 4, we can see how frequently clients at HFH shelters were denied eligibility. While nearly 40% of clients were deemed eligible almost immediately, the majority were denied at least once.

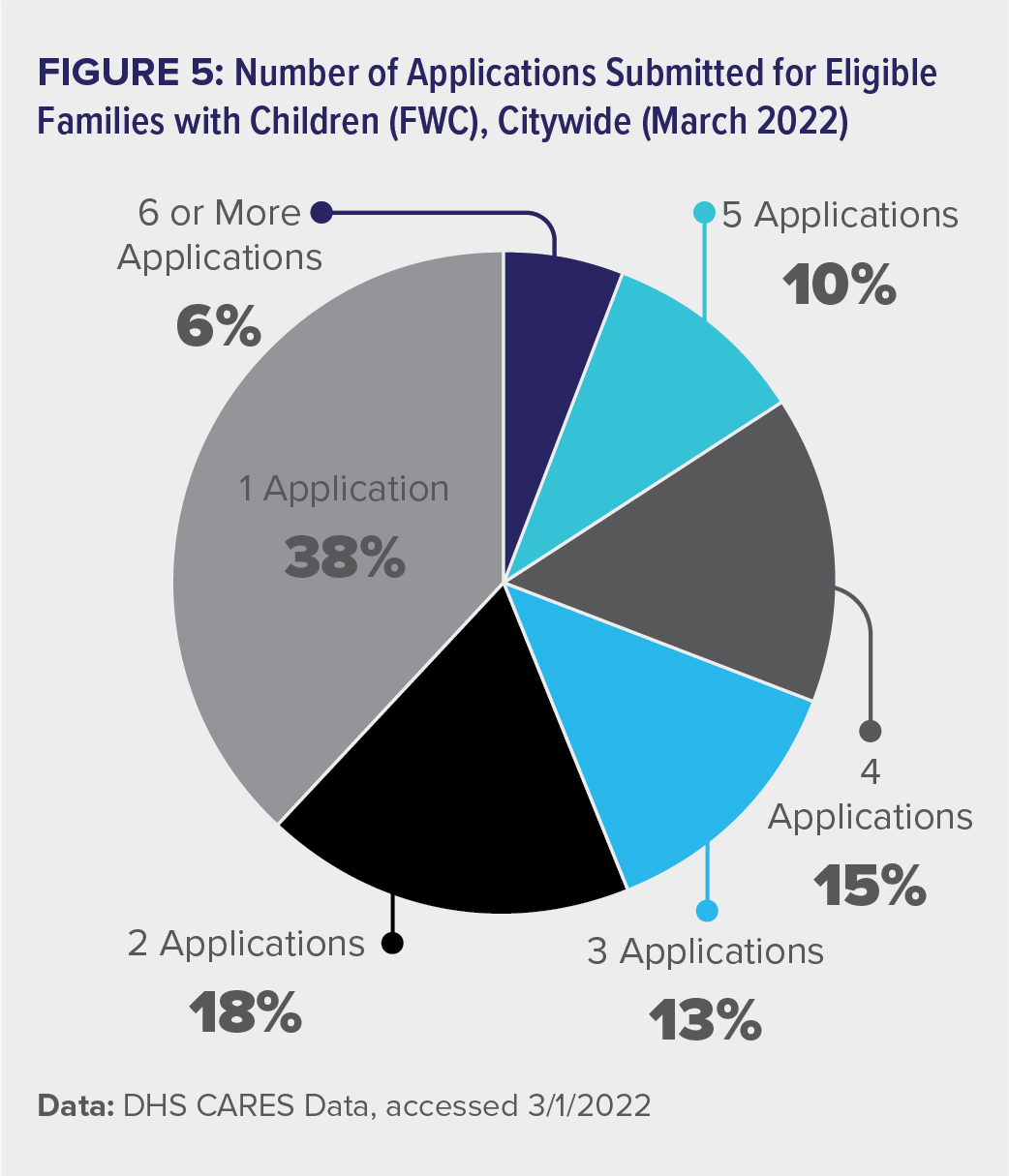

This issue is not just prevalent in HFH shelters; the same issue exists citywide, across all DHS family shelters, as seen in Figure 5. The majority of shelter applicants are denied more than once.

Over the last three years, fewer and fewer families system-wide have been found eligible after their first application. Almost 60% of shelter applicants were found eligible for shelter on their first application in January 2019. In March 2022, that number is below 40%. While DHS does not release data on the proportion of families with children in all shelters who are currently conditional, it is clear that many families are forced to repeatedly reapply for shelter eligibility.

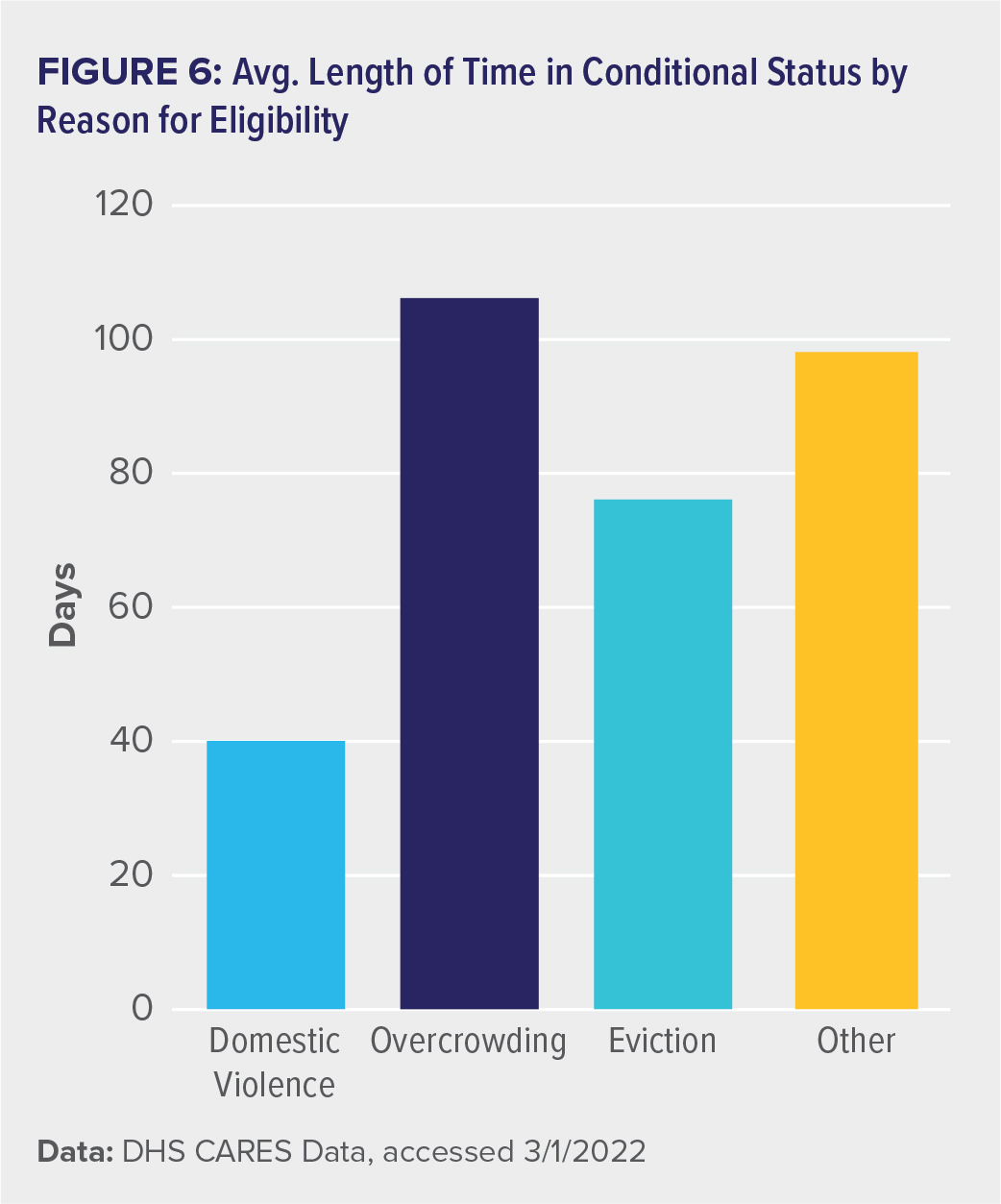

When HFH families are finally found eligible for shelter, it is usually attributable to one of three reasons. The most common reasons among clients for being found eligible for shelter are domestic violence (41%),15 overcrowding (24%), and eviction (16%).16 Figure 6 shows the average length of time that families are conditional by the reason for their eligibility. Clients who are eventually found eligible because of domestic violence tend to have shorter time spent in conditional status than those who have other reasons for entering shelter. This difference is likely due in part to DHS determining overcrowding situations as viable living arrangements whereas situations where families are experiencing domestic violence are not. Families who come into shelter because of eviction or overcrowding situations spend significantly more time in conditional status.

Note: Citations and sources for data are included in the PDF version of this document available by clicking Downloads underneath the Table of Contents.

A Broken Process

As the process purports to work, a client is notified at the end of a 10-day investigation as to whether they have been deemed eligible or ineligible for shelter. This notice is currently delivered to clients by shelter security staff, either in-person or slipped under clients’ doors. Once a client receives this notice, they must call PATH to be reinstated into the shelter system and to reapply for eligibility for shelter. As the policy stands currently, this must be done by 5 p.m. the day after they receive the notice, and if they do not get in touch with PATH by this time, they must return to PATH in the Bronx to be reinstated. Once they are reinstated into the system, they receive a new case number and must meet with shelter security and case management to complete intake forms and processes.

For most clients who are experiencing homelessness and have sought out shelter, a determination of ineligible by DHS merely means they must reapply for shelter, either seeking out more proof of previous residences or attempting to prove to DHS that an address that they cannot return to is truly not an option.

Prior to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, families always had to return to the PATH intake center in the Bronx to reapply for shelter, bringing along with them all of their belongings for another grueling day of waiting, retelling the traumatic details of what led them to shelter, and filling out paperwork. They would then be assigned another, potentially different, conditional shelter placement, where they would go for another 10 days.

Because of the importance of keeping families stably housed and limiting exposure to the virus, this process was changed following the onset of the pandemic. Now, clients reapply by calling PATH to become reinstated. There are many benefits to reapplying over the phone without having to travel to PATH and without losing a shelter placement. However, the process is still burdensome, frustrating, and inefficient for families and shelter staff.

Getting in Touch with PATH

Overwhelmingly, clients express frustration about the difficulty in connecting with PATH by phone. Clients describe hours-long waits, time spent on hold, or nobody picking up the phone entirely. They leave voicemails that are not returned for days. Clients try calling at various times of the day to get in touch with someone, and some noted that during traditional working hours there is a higher likelihood of reaching someone, despite PATH’s hours of 24/7. Of course, this means that a client may need to take off time from work or call in sick to be able to get reinstated efficiently. In one case, the frequency with which a client had to go through this process demotivated a client from seeking employment.

If a client leaves a voicemail, clients do not know when PATH will return the call and what number the worker will use. Sometimes, the numbers show up as spam numbers and clients are hesitant to answer. This, too, prolongs the process.

When a client does get hold of PATH, they are quickly reinstated into the shelter system. They must then wait for two to three additional phone calls, one of which will detail what PATH requires for them to be deemed eligible. The clarity of these details depends heavily on the PATH worker who calls a client, with some taking the time to explain what is needed and some repeating the same information that clients receive on a form that alerts them of PATH’s determination. These additional calls may take place on the same day a client calls, or can happen anytime during the following week, leaving clients in limbo.

“You have to call and every time I call, I’m put on hold, or the number’s not working, or the line’s busy. And I was working. They want me to stop my life. I still have to work; I still got a job to do. And by the time I can call—afternoon hours—it’s impossible to speak to anybody.”

— 28-year-old single mother of an eight-year-old child, conditional for 571 days

“Once they say I’m eligible, it’s like a boulder will be off my back. Because then I don’t have to worry about [how] every 10 days, I got to call PATH.”

— 30-year-old single mother of an infant, conditional for 280 days

Increasingly, DHS relies on shelter staff to assist and monitor clients seeking reinstatement. Shelter-based case managers are encouraged to sit with clients to ensure they are calling, which can take up hours of a case manager’s day as they wait on hold. This detracts from the other work they need to do—most importantly, assisting clients with seeking employment and exiting shelter. Attaining eligibility is the first step on clients’ lists of tasks to accomplish; without eligibility, they are precluded from receiving various services so it is paramount that they resolve their status as quickly as possible. With so many clients in conditional status, HFH staff spend a disproportionate amount of time working to get them eligible compared to time that could be spent on tasks that could be more beneficial to clients and their families in the longer term.

“Sometimes I’ll call PATH with a client and be on hold for an hour—and that’s an hour I can’t be doing other things [such as providing referrals to social services or performing other tasks that help families prepare for maintaining permanent housing].”

— Case Manager

Submitting Documentation

Clients must submit proof of where they lived for the last two years. The most common reason for denial of eligibility for families in HFH shelters is “incomplete housing history,” which means that the client hasn’t provided sufficient proof.

This proof is often onerous and sometimes impossible to procure, especially for families who previously lived on the street or for families recently immigrating to the United States seeking asylum. Clients who lived on the street may have to ask employees of stores adjacent to where they bedded down or places where they took a shower to write a notarized letter on their behalf. Not only is this quite an ask to make of a stranger, but it may be impossible to find someone who can vouch for having seen them living on the street.

Clients who were kicked out of their previous residences also shared difficulties in submitting the required paperwork. One client’s mother locked her out of the apartment and then left the country. After being denied eligibility because PATH believed the client could still stay in the mother’s apartment, the client had to ask her mother in another country to find a notary and send a letter saying that she had been kicked out of the apartment and could not return. It is easy to imagine that many family members who have fraught relationships with clients currently in shelter would not be willing to fulfill such a request.

Each day over the past two years must be accounted for, which can also be difficult for those who stayed in a motel. One client shared that she was in one for a mere two days, paid in cash, and the motel did not keep detailed logs of their guests, so she could not prove it.

A last major issue with this requirement is the fear that family members or friends who live in NYCHA apartments may feel in disclosing to PATH that a client stayed with them at some point. NYCHA is strict about apartment composition, and tenants can be evicted for allowing people to live with them who are not on the lease. Concerns about eviction can make providing evidence of temporary residency at a NYCHA apartment challenging, as clients typically wouldn’t have been able to receive mail there, have bills in their name, or have a friend or family member admit to their stay.

Not only is this two-year housing history proof difficult to compile, but the process for submitting documents is disconcerting to clients and staff. There is one fax number dedicated to receiving this paperwork for all conditional clients across the city. Alternatively, clients and staff can email documents using a general email address. This is no doubt frustrating for PATH employees as well, making it more difficult for them to find and organize these documents. Clients and staff do not receive confirmation from PATH as to whether their documents have been received. Instead, they must wait for their next determination of eligibility, which may still not make it clear if documents were received or if the documents were unacceptable. In some cases, clients submit the same documentation repeatedly because they believe it is what PATH is asking for; it is difficult for them to know what the issue with their application truly is.

Clients can request a “fair hearing” with DHS if they feel their eligibility has been denied unfairly. Since the onset of the pandemic, fair hearings take place over the phone with a judge. During this call, clients share their experience with the judge in the hopes that they can be found eligible, though there is no guarantee of a desired outcome. Several HFH clients reported that they had participated in one to multiple fair hearings without achieving eligibility.

Unfair Playing Field

Many HFH staff noted that characteristics about a client, such as their temperament, played an unfair role in eligibility determinations. The better a client is at advocating for themselves, the faster their eligibility may be determined. Clients who are assertive, fluent in English, and better educated or more literate are often able to get clearer guidance from PATH, or have their eligibility determined by consistent pressure. As others have noted, depending on which PATH worker answers a client’s call, they may have an easier or more difficult time getting information. Similarly, depending on a client’s own temperament and skills, they may be trapped in conditional status for days to months longer than other clients.

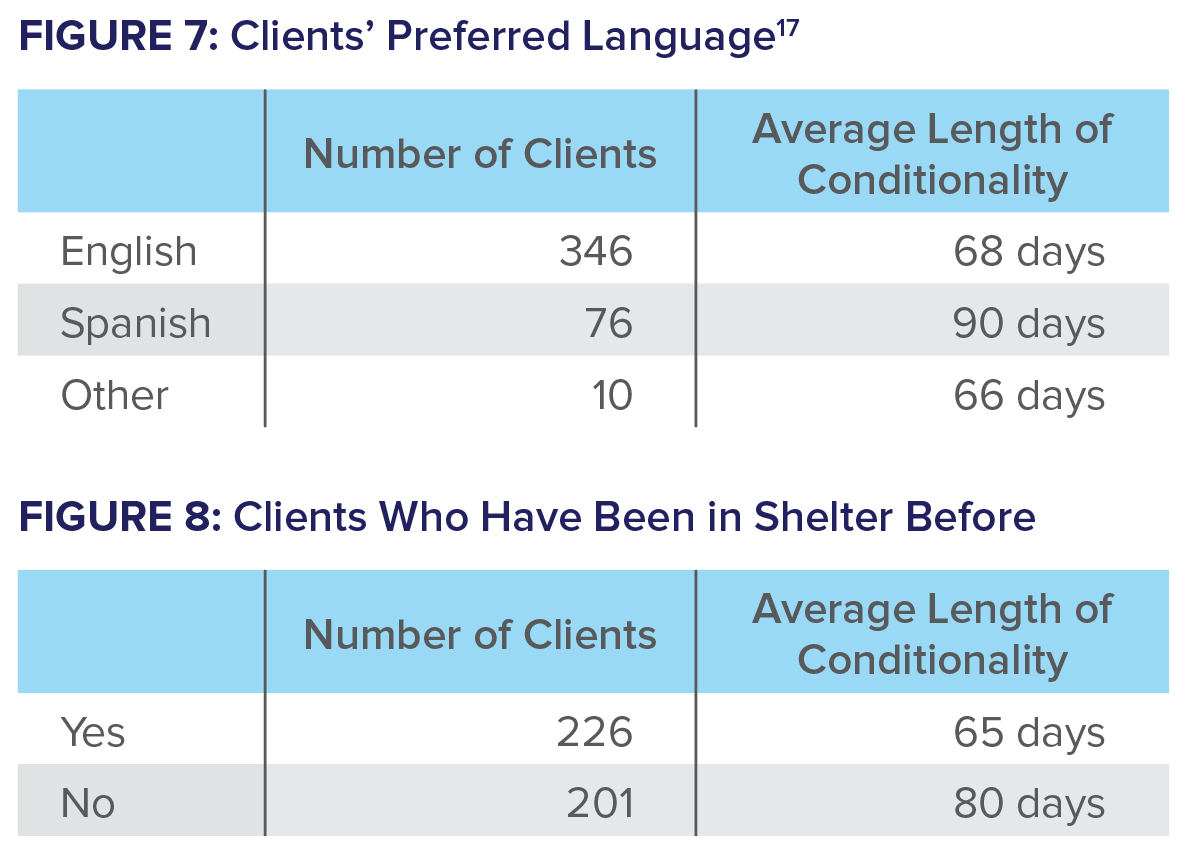

In examining some of these characteristics in the population of clients at HFH shelters, one can note that Spanish speakers spend more time in conditional status. Newcomers to the shelter system, who may be unfamiliar with DHS processes, also spend a longer time in conditional status. It is important to note that these analyses do not take into account many other potential confounding variables that could contribute to an increase in length of time in conditional status. Publicly available data from DHS on the length of time families spend in conditional status within the entire NYC shelter system would be beneficial for understanding why some families are stuck in conditional status longer than others.

Note: Citations and sources for data are included in the PDF version of this document available by clicking Downloads underneath the Table of Contents.

The Toll It Takes

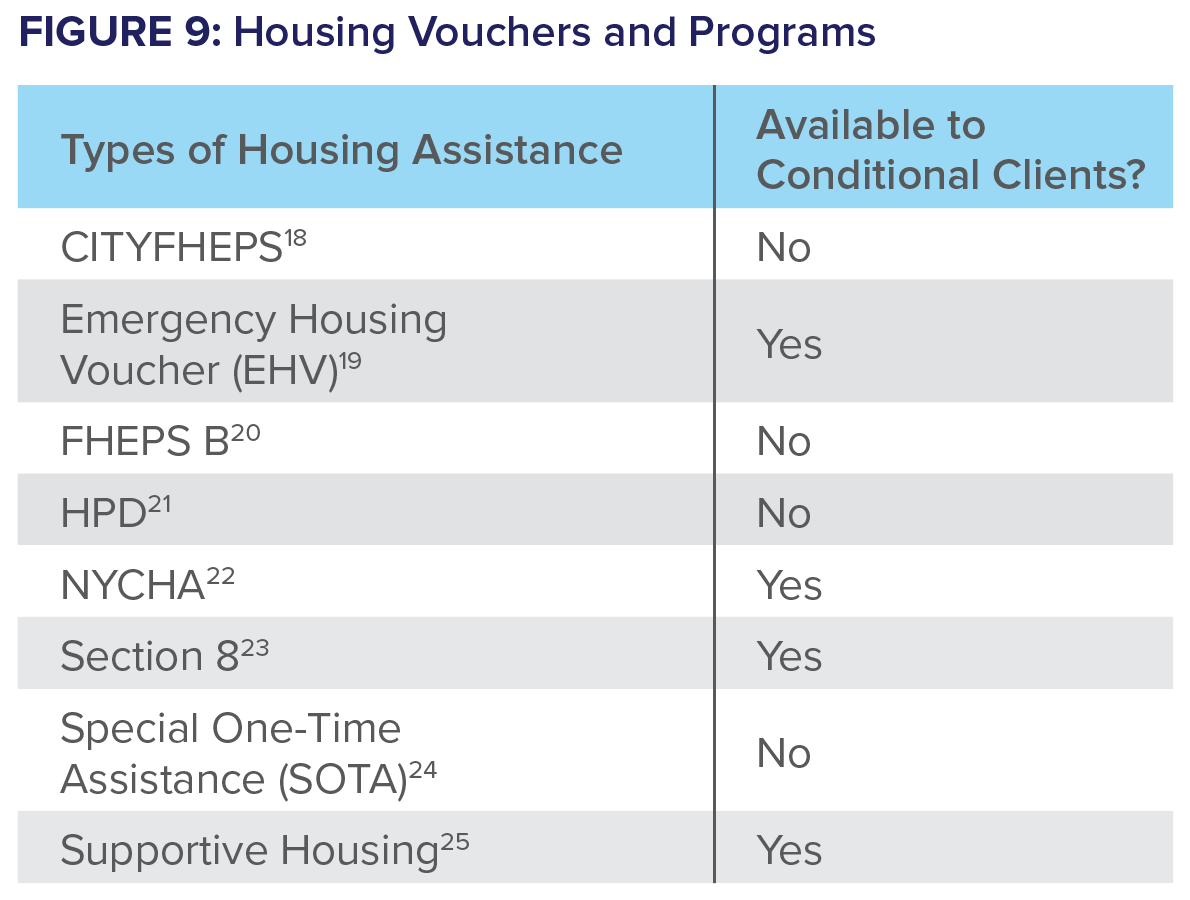

Extended time spent in conditional status takes a toll on families. A significant concern for families is that it leads to a prolonged shelter stay. When a family is in conditional status, they cannot access various housing subsidies to help them exit shelter, such as CityFHEPS. To obtain a CityFHEPS voucher, a client must be found eligible for shelter and live in shelter for 90 days—the time spent in conditional status is not included in the 90 days. For the average HFH client who is conditional for 40 days, their wait to receive assistance moving out of shelter totals nearly four-and-a-half months. Figure 9 shows the types of housing assistance available to shelter clients; half of these programs are not available to clients in conditional status.

Families and case managers at HFH shelters noted that delays in eligibility determination can create increased levels of stress.

Continual denial of eligibility also deteriorates the relationship between clients and their case managers, as they often come to see the shelter where they’re staying and the staff whose goal it is to help them as to blame for the difficulties they experience with PATH.

Clients also become frustrated with the need to repeat their intake paperwork and initial meetings, which must happen every time they are reinstated. Oftentimes, they begin to shrug off meetings with case managers completely because of their frustration. This makes working with them, even if they do eventually become eligible, much more difficult.

This process takes a toll on staff, too. Many staff expressed that their fulfillment comes from helping clients achieve stability in their lives. When their only interactions with clients center around submitting documents to prove eligibility—a process that is not transparent and one over which they have no control—it can be at best redundant and at worst demotivating.

Furthermore, staff experience burnout from processing a new version of the same paperwork for each family in conditional status every 10 days. The process does not appear to be a good use of the finite resources available to support families experiencing homelessness.

Note: Citations and sources for data are included in the PDF version of this document available by clicking Downloads underneath the Table of Contents.

What Clients and Staff Say about the Toll It Takes

About Housing …

“Our whole family is from the Bronx; all of our friends and family [are] there, my work is there. I have to wake up at 4:30 am to get to work, and I call out a lot of the time because I am so exhausted. It’s hard to push things forward, especially with being named ineligible so many times. It limits our housing options because you have to be eligible. So, we can’t get an apartment easily, which means we can’t be where the majority of our family is.”

— 21-year-old mother of a two-year-old child, conditional for 311 days

“I’m working. [And] being a mom is a full-time job, especially with the dad not in the picture. It’s frustrating; I have so many other things to do … it’s a lot of juggling and for once, just one thing in my life needs to be situated. If somebody could help me get out of this situation where I feel you know, okay, this is a stable place, I can feel comfortable, and I know I won’t have to get up and move all over again 10 days later. That’s how I’ve been feeling—I moved from the City to Queens back to the City now to the Bronx, and it’s a lot for me and my daughter …”

— 22-year-old single mother with a two-year-old child,

conditional for 232 days“My case manager told me I’m eligible for housing programs, but I have to be eligible [for shelter] first. That’s the only thing in the way.”

— Gregory, 38-year-old father of a five-year-old child,

conditional for 117 days“When I did have a job, nobody here could help me, nobody could get me a voucher, nobody could get me an apartment—why? Because DHS found me ineligible. So now [that I’m unemployed] I’m back to square one. I’m stuck here longer. I got to find childcare. I got to find a new job, and it just delays my whole process. It pretty much backfired.”

— 28-year-old single mother of an eight-year-old child,

conditional for 571 days

About Stress …

“Every 10 days, I was denied, and it was so stressful that I was losing hair and losing weight and I was pregnant [and my daughter’s] heart rate started dropping.”

— 30-year-old single mother of an infant, conditional for 280 days

About the Relationship Between Client and Case Manager …

“It’s hard as a manager to motivate staff to deal with this—especially since clients get mad and frustrated at staff when they’re not found eligible—[they say] you didn’t send in my paperwork.”

— Family Services Director

“I was frustrated—to be honest, I thought the folks here [at the shelter] weren’t doing their job. I wanted to take it out on them.”

— 40-year-old father of a teen son, conditional for 59 days

About Burnout …

“The eligibility process needs to be better so that we can better assist these clients. Otherwise, we have clients here for months and years that are still conditional and their feeling is ‘you’re not doing anything for us.’ And that’s frustrating for us to hear as case managers because that’s literally all we want to do.”

— Case Manager

“When I first started, I thought my caseload was cursed because more than half of my clients were conditional, and I found a lot of them were found ineligible sometimes north of 10 times.”

— Case Manager

Areas for Change

1. Change Eligibility Requirements

As WIN, another NYC family shelter provider, and others have voiced,26 providing two years of housing history is a burden that doesn’t seem to correspond to determining a family’s need for shelter. Shortening the time required to one year will remove some barriers for families who have difficulty providing all the necessary documentation two years back. It is critical to remember that these families are experiencing the trauma that is homelessness; they may not be able to retain their documents or keep them organized as they handle the life emergency that has sent them to shelter.

It may also make sense to consider a client’s consistent residency in shelter as proof enough of shelter need. As many HFH staff pointed out, if a family is in shelter each and every night, doesn’t that demonstrate that they have nowhere else to go? Granting eligibility after a certain number of nights consistently in shelter might assist families in becoming eligible when they are in a period of prolonged ineligibility due to circumstances beyond their control.

2. Improve Communication Between PATH and Shelters and Clients

It is clear that the methods of communication between PATH and shelters and clients create challenges for shelter staff and families. Below are some ideas for how DHS and shelters could improve this issue. The ideas below are not exhaustive; there are many possible ways to tackle the myriad problems.

More PATH Employees Answering Phones

The inability to get in touch with PATH easily by phone or email to reapply, confirm document receipt, or check the status of a case is very challenging. The first issue that seems clear is that more workers are needed to service the phone lines at PATH to respond to families. Spending hours calling, or days waiting for a call back, is frustrating, puts other life tasks on hold, and creates dread for clients. PATH employees, too, may feel overburdened and overwhelmed by the high call volume and lack of adequate staffing to meet clients’ needs.

Direct Contact at PATH or Online Portal to Ease Submission of Documentation

Working with a direct contact at PATH as opposed to sending documents to a general email and fax number would help with several elements of the process. For one, this person could send a response when documents are sent to PATH so that a client can be sure that they’ve done all they can to move their case forward. This email would also help them to understand, in the event they are denied, if the documents do not meet PATH’s requirements, or if they were just not received.

Often, clients visit their case managers at HFH shelters to ask what the status of their investigation is. It would improve trust in case managers—and in the process—if case managers had an ability to communicate with PATH easily, perhaps through this one contact. As shelter case managers are the ones managing the process on the ground, it is important that they can access information about why denials are happening, what clients need to do to be found eligible, whether documents are received, etc. more easily and quickly.

Finally, having one person working on a client’s case at PATH would ensure that the client does not have to repeat themselves, telling their story or sharing why certain documents are impossible to procure. This would relieve some of the emotional stress of reapplication.

Using the online portal, CARES, which shelter staff already access to upload intake documents and organize case notes, as a repository for housing documentation could also serve to ease submission and confirmation of receipt of documents. If case managers could upload these types of documents to CARES, which could then be reviewed by PATH employees, clients and staff would feel confident that documents had been received by PATH and could even be notified when documents had been examined. Using the CARES portal as a way for staff to communicate directly with PATH about documents that are missing or unacceptable would decrease confusion about the process. If it were not feasible to work with one PATH worker due to employee turnover or other factors, the portal could serve to improve communication.

In-Shelter Staff Member Focused on Eligibility

Many staff at HFH shelters voiced a desire for a staff member who is not a case manager to focus on working with clients to prove their eligibility. This staff member could be an in-shelter DHS position or PATH worker, structured similarly to the Department of Education (DOE) liaisons who work in shelters to assist parents with enrolling their children. This could also be a position within the shelter provider’s organization. Hiring such a person would remove some of the burden from case managers in focusing their energies on, as one staff member put it, “the front end.” It also would ameliorate some of the tension in the case manager-client relationship. Finally, it might help clients take their case management meetings more seriously, as they would be distinct from meetings about eligibility, which are typically meetings they eschew.

Clearer Guidelines on How to Prove Eligibility

While providing a two-year housing history might seem straightforward, it is a confusing request for many clients for several reasons. First, there is no clear list of what constitutes proof. Is a lease or six pieces of mail sufficient or is a bill required as well? Will a letter from a roommate and a text from a landlord be enough?

Secondly, the time period of two years can confound clients. One HFH client lived at the same address for more than two years. When applying for shelter, he sent in his original lease and bank statements that showed that he had lived there since 2019. It was difficult for him to understand that PATH only wanted to see proof from 2020. Because of this misunderstanding, he spent 59 days in conditional status.

A multilingual resource that detailed how to show proof of living situations within the specific time periods could help families become eligible more quickly.

Longer Time to Determine Eligibility

From the number of clients who are denied multiple times, it seems that one issue may be that 10 days is not long enough to determine eligibility. Perhaps 20–30 days would give PATH investigators time to work with clients on collecting and sharing their documentation, and time for them to get in touch with the client’s contacts. If this investigative period were longer, shelter staff would spend fewer hours redoing intakes with clients, reorganizing files, and sitting with clients on hold with PATH. Clients would also spend less time on the phone with PATH and be able to use that time to take care of other tasks. For some clients, their lives revolve around the 10-day denials they experience; this would alleviate the constancy of the reapplication process.

3. Create Earlier Access for CityFHEPS

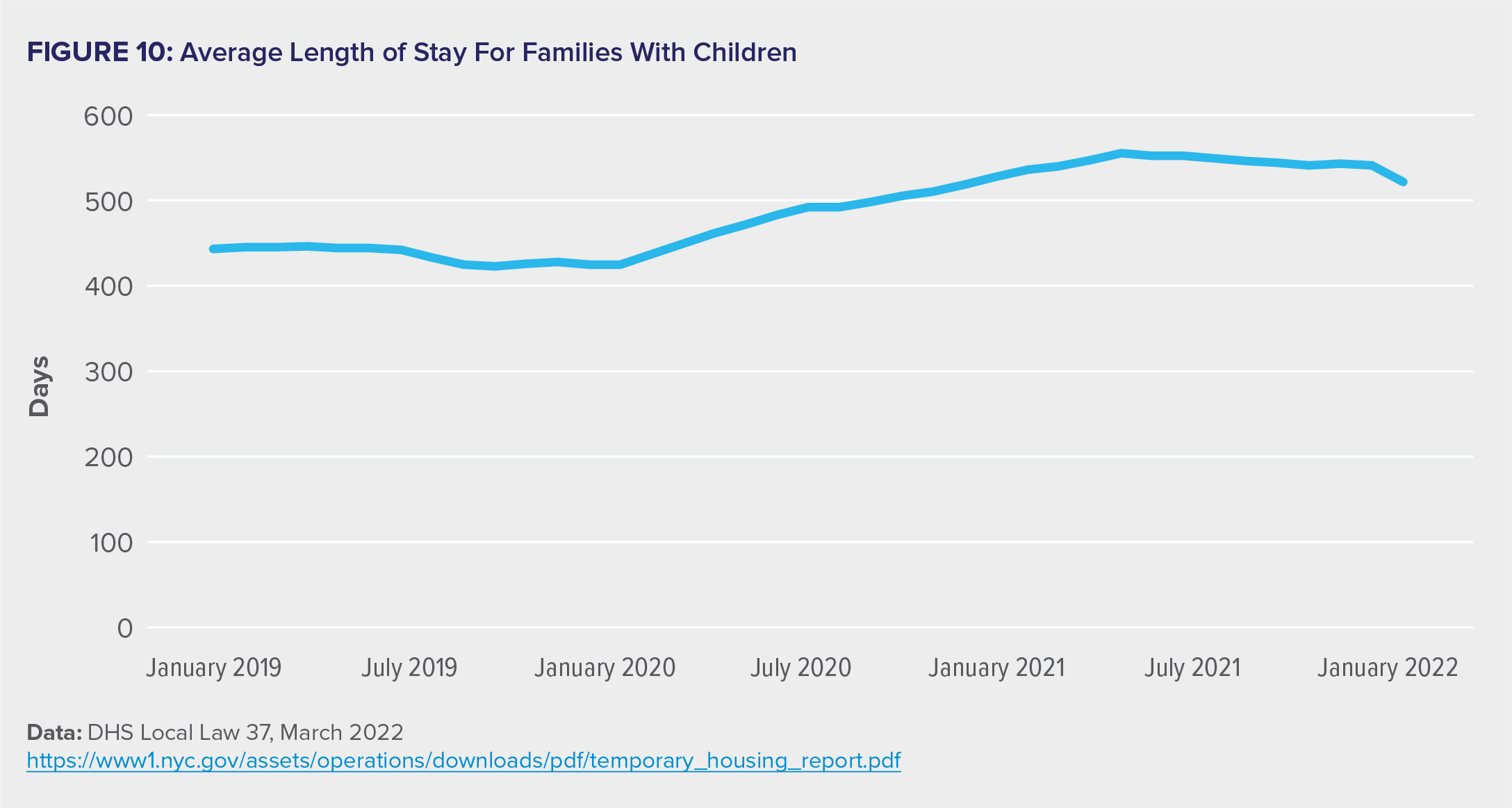

Waiting an additional 90 days after finally becoming eligible for shelter to become eligible for a CityFHEPS voucher is a waste of time for clients and a waste of resources for DHS. Including some or all of the time spent conditional in the 90-day wait would help clients move out faster. As the average length of stay for families with children continues to increase and is currently nearly a year and half,27 DHS should consider ways to expedite families exiting shelter and achieving stability.

Note: Citations and sources for data are included in the PDF version of this document available by clicking Downloads underneath the Table of Contents.

Conclusion

Clients end up in shelter for various reasons, but typically do not want to stay long. Repeatedly, clients expressed frustration at this eligibility hindrance that kept them from accessing services and feeling settled enough to take care of tasks that will help them achieve stability. After several denials, when the issue is clearly that a piece of proof doesn’t exist, continual denials only serve to incentivize lying about either where clients were, or who they stayed with—the very concern this eligibility process is meant to root out.

The mayor’s plan, Housing Our Neighbors: A Blueprint for Housing and Homelessness, released in June 2022, dedicates an entire chapter to reducing administrative burdens, recognizing that antiquated systems and processes often keep families in shelter longer, delaying them from accessing housing. However, the administration did not take the opportunity to reimagine the eligibility criteria and process in the plan, despite the enormous administrative burdens it presents to clients and DHS staff.

“I want to get started on housing. But I have to get this done first. I want to get out of here. I’m worried about getting too comfortable in a place like this. Which can happen. Me and my husband have to catch ourselves when we call it ‘home.’”

— Currently pregnant 39-year-old client, conditional for 168 days

It is critical that clients not languish in conditional status. The high proportion of clients in conditional limbo detracts from the shelters’ overall goals of supporting families in establishing their mental, physical, and financial health and taking steps toward independence. Further, it is currently an unnecessarily long and punitive process whose only certain result is keeping families from services they need.

Note: Citations and sources for data are included in the PDF version of this document available by clicking Downloads underneath the Table of Contents.

The writing and research for this report was conducted through June 2022.

For additional copies or inquiries: E-mail INFO@ICPH.org