A Policy Research Commentary

October 2016

Editors’ Note: The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development has shifted its funding priority toward rapid re-housing, its chosen intervention for tackling the homelessness crisis. As HUD continues to study the effectiveness of rapid re-housing strategies through its Family Options Study, ICPH wants to give a voice to those on the front lines who are navigating this transition. While the jury is still out on rapid re-housing, the experiences of service providers raise important questions about what is needed to permanently end a family’s homelessness.

In 2007, when Kimberly Tucker became director of the Flagler Home, a transitional family shelter just outside of Richmond, VA, she found herself in charge of a much beloved community institution in this historic, Southern city of about 220,000 people on the East Coast.

Flagler Home was founded in 1989 by St. Joseph’s Villa, a large private nonsectarian multi-service agency, to provide transitional housing and support services for homeless mothers and their children. As Tucker describes it, they offered “all kinds of life skills and workshops and training and support to be able to not just help resolve their homelessness, but to hopefully never become homeless again, and for people to become self-sufficient when they get out.”

Little did Tucker know that six years later, she would recommend Flagler’s closure to her parent organization, rewriting all the job descriptions and making her entire staff reapply for their positions, as they shifted to rapid re-housing.

Growth of Rapid Re-Housing

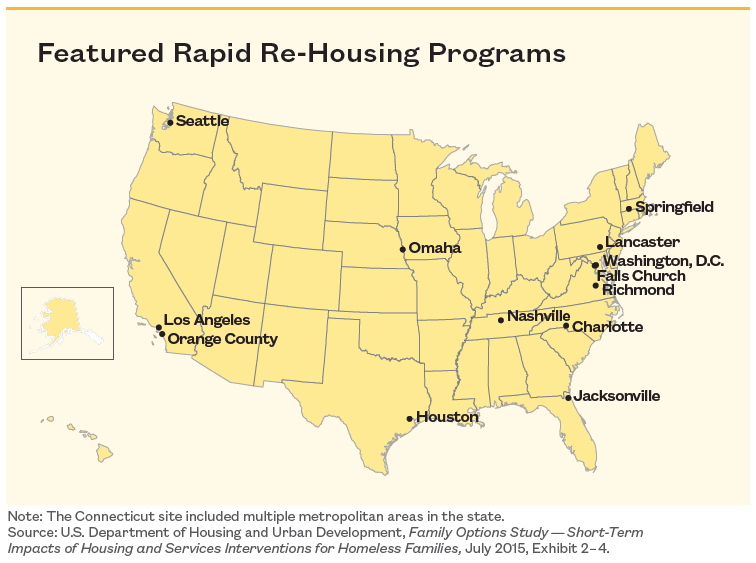

Fueled by a wave of federal funding from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), communities from coast to coast have implemented rapid re-housing programs—sometimes with enthusiasm, and at other times with trepidation.

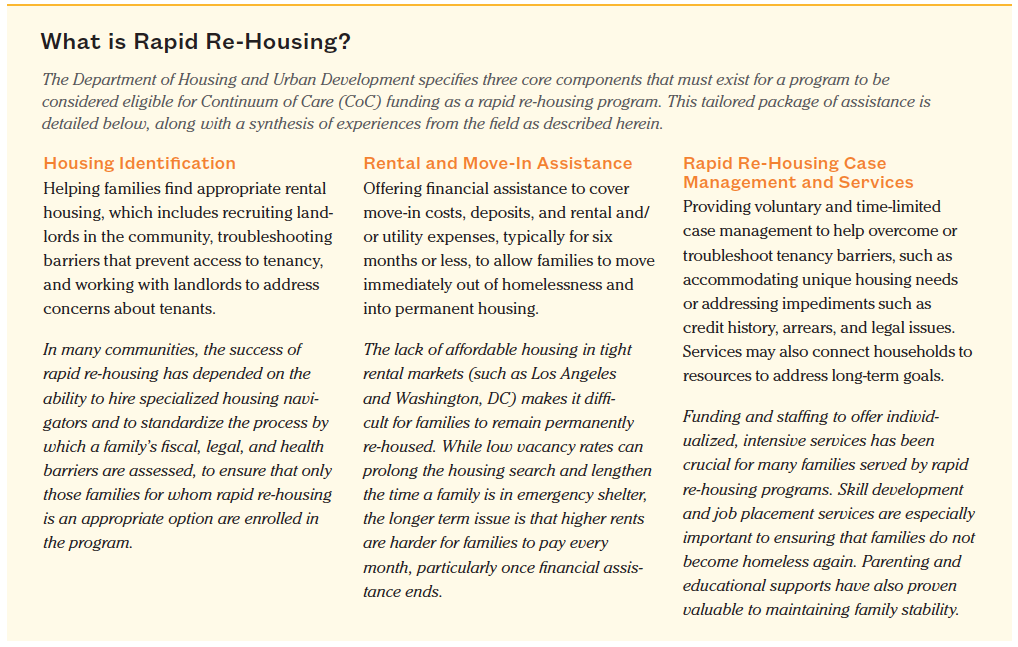

Rapid re-housing aims to help families exit homelessness and return to permanent housing, ideally within 30 days of entering a shelter. Programs generally provide short-term subsidies, case management, and an array of support services, for anywhere from four months up to a year or longer, depending on the community. Unlike transitional programs, which may place conditions or restrictions on families for participation, rapid re-housing does not require sobriety, employment, or other conditions for eligibility.

Rapid re-housing for homeless families is not a new concept. Beyond Shelter in Los Angeles began using the approach in 1984 (the organization has since merged with the larger nonprofit PATH). In Lancaster, PA, a small city of about 55,000 in its urban center, and a metro-area of about half a million, the Shelter to Independent Living (STIL) program has been operating since 1992 and was cited in a case study by HUD on successful models for rapid re-housing.

HUD made its first foray into rapid re-housing in 2007, when Congress appropriated $25 million for a demonstration project for families, later selecting 23 communities to participate. The idea, says Ann Oliva, deputy secretary for special needs programs at HUD, was to “build our knowledge,” to learn what rapid re-housing is and how it works with different types of families. In the study, HUD looked at how 500 families in the pilot fared a year after release from the program. Among other findings, the study showed that 76 percent of families moved at least once in the 12 months after leaving rapid re-housing, and ten percent of all households experienced an episode of homelessness in that period.

Two years later, as America reeled from the effects of the biggest economic downturn since the Great Depression, Congress passed the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, which President Barack Obama signed into law on February 17. Embedded in that bill was $1.5 billion for the Homelessness Prevention and Rapid Re-Housing Program, or HPRP.

Oliva says that the advent of HPRP marks the first time the agency tried out rapid re-housing at scale. “We were very young in our development of what good rapid re-housing as an effective project looked like,” she says. “We learned a lot through the course of three years. We actually ended homelessness for 1.3 million people.”

Later that year, Obama signed into law The Homeless Emergency Assistance and Rapid Transition to Housing Act, better known as HEARTH, which reauthorized the McKinney-Vento programs run by HUD and legitimized rapid housing as an effective model for reducing homelessness.

In 2013, HUD released a memorandum that endorsed the use of TANF (Temporary Assistance for Needy Families) funds to pay for rapid re-housing programs. The next year, in 2014, the Veterans Administration authorized funds for rapid re-housing for veterans and their families. That same year, the U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness issued its plan for ending family homeless by 2020, with rapid re-housing a cornerstone of the efforts to make homelessness a “rare and brief occurrence.”

For Fiscal Year 2014–2015, HUD funded almost twice as many rapid re-housing projects as in the previous year, says Oliva. “For several years, we have really been pushing our communities to evaluate all of their projects and look at system performance and project level performance,” she says, acknowledging that there has been a “significant decline” in funding to transitional housing and supportive housing. “As national policy, we want to provide as much housing as we can through our program. We are the only federal agency that does housing.”

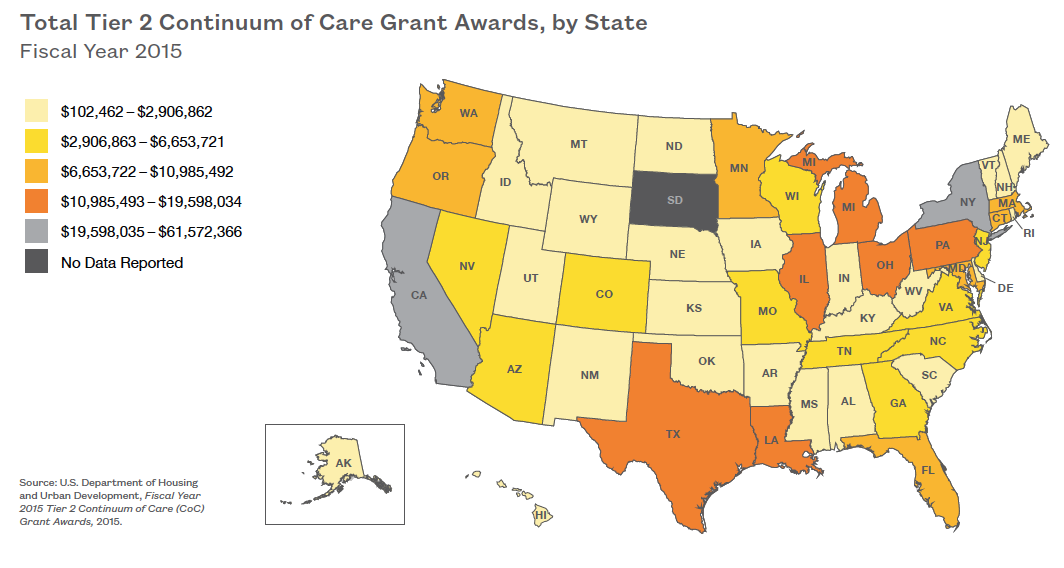

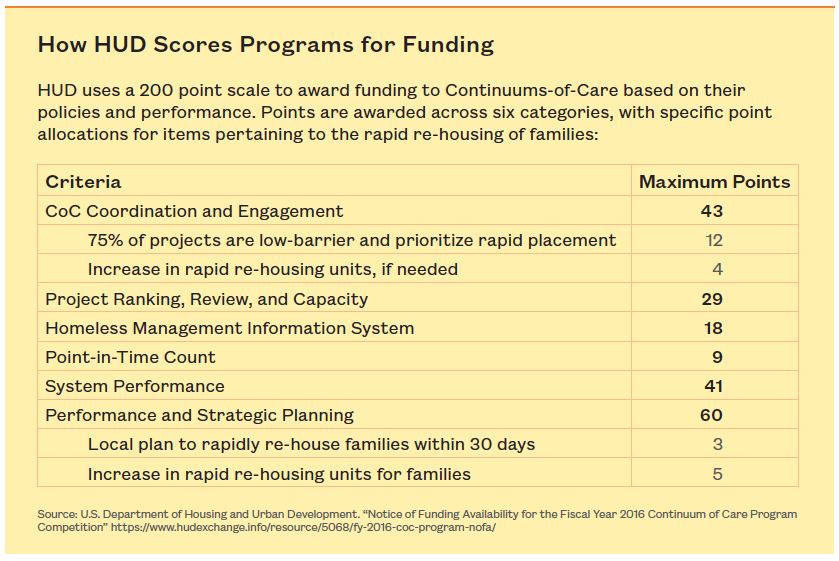

HUD also shifted 15 percent of its funds, or $355 million, into Tier 2 Continuum of Care, where communities competitively bid for funding and are scored according to a formula that gives more points to programs that emphasize rapid re-housing and permanent supportive housing, over transitional housing.

Last year, HUD released the interim findings of its Family Options Study, the largest experimental study ever conducted to test different interventions designed to address family homelessness. HUD has not yet released the full results of its three-year study which began in 2010; however, the interim findings based on the first 18 months comparing permanent housing subsidies, rapid re-housing, transitional housing, and the usual care at the local level are mixed and inconclusive.

Who Does Rapid Re-Housing Work For?

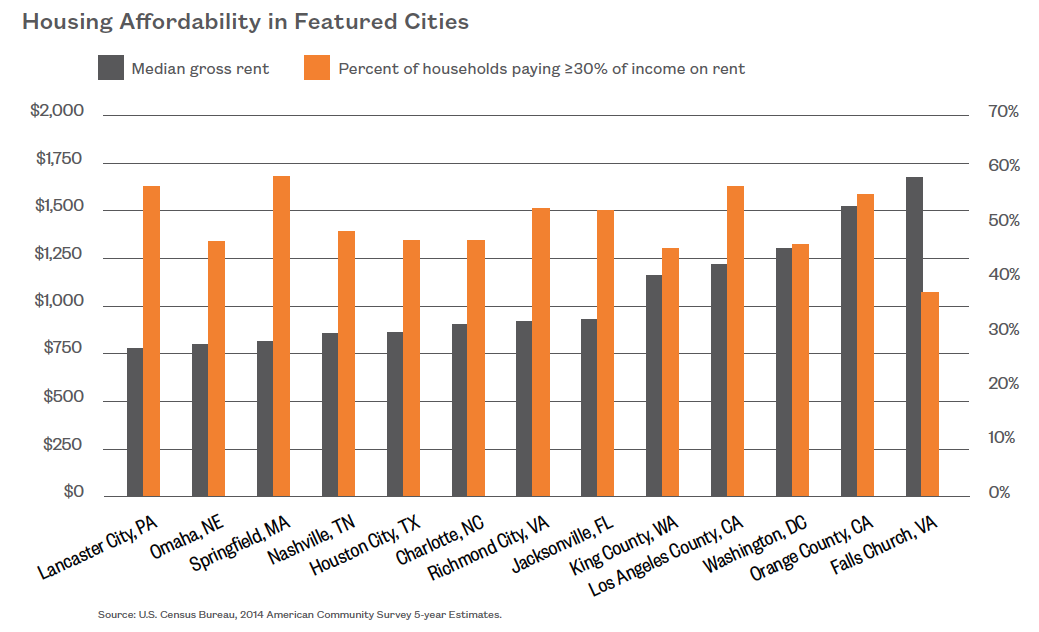

Critics say that families who are rapidly re-housed will wind up back on the street if the root causes of their problems are not addressed. Christopher Fay, who runs Homestretch, a coalition of churches and community people that support programs to end homelessness in the Falls Church, VA suburb of Washington, DC, says the requirements Homestretch imposes on participants in its two-year transitional shelter program assure greater success. “Our theory is to take time with the family to equip them with skills and pay off their debt,” he explains. “You have to address poverty. We are ultimately saving people from lives of homelessness by driving them out of poverty.”

Proponents, on the other hand, say getting a roof over people’s heads is the priority and that ending poverty is a much bigger task for society to tackle, one that requires the resolve of policymakers and politicians and a commitment to creating more affordable housing. They say that a family that is traumatized by homelessness and is thrust into the chaos of shelter life cannot focus on turning their lives around until they get housed.

In Tucker’s case, she realized that the majority of people leaving Flagler Home were not moving into permanent housing. “Oftentimes they were like, ‘I have had it with the rules’ and would move out in a huff.” People were also not getting jobs, for the most part, although she had an employment specialist and an onsite childcare facility. She tried everything: making the rules more relaxed, making them less relaxed. She tried morning meetings. But nothing seemed to be working.

In 2010, Tucker launched a small-scale, privately-funded pilot project to begin rapidly re-housing “low-barrier families”—those who only have a few factors that make it difficult to obtain housing. She converted one of their case managers into a housing specialist who began working directly with landlords to find housing for their clients. The results were encouraging: “We housed about 30 people, and they seemed to stay housed,” she says.

During this time, Tucker reduced the average length of stay, first from two years down to one, and then to six months. “We said we were pretty much a shelter with a housing focus,” she recalls. “When you walked in, you did not have a case manager anymore. You had a housing specialist to help you find housing, and you had an employment counselor who could help you find income.”

In June 2013, St. Joseph’s Villa closed Flagler for good and converted all their efforts to rapid re-housing.

Tucker also says that, a year after leaving the rapid re-housing program, almost 100 percent of their clients have stayed out of homeless shelters.

More than 3,000 miles away in the Los Angeles suburb of Orange County, CA, William O’Connell, executive director of Colette’s Children’s Home, tells a different tale about serving homeless mothers and their children from the Southern California towns of Anaheim, Huntington Beach, Palencia, and Fountain Valley. Very few of the single-mother families who come through the doors of Colette’s Children’s Home are low-barrier.

“Rapid re-housing will work for high-functioning folks,” says O’Connell, as he explains that the majority of mothers seen by his nonprofit transitional shelter and permanent supportive housing provider have three or more “high-risk” issues like substance abuse, mental health issues, experienced domestic violence, have long unemployment histories, felony convictions, or lack of transportation.

“We often get into our camps as if there is one option that would work for everyone,” says Eva Thibaudeau, director of programs at Houston’s Coalition for the Homeless, the Continuum of Care lead agency for three municipalities in the greater Houston area. “We know that is not true. With every population, we are trying to build up choices.”

In Charlotte, NC, a metropolitan area that includes the city proper and the more suburban Mecklenburg County that Charlotte Family Housing Executive Director Stephen Smith calls “up-and-coming with a lot of tech companies and rents that are starting to get higher,” the issue is not rapid re-housing vs. transitional shelter; it is sustaining vs. obtaining housing. Smith’s agency typically serves working families who are experiencing homelessness.

“We are struggling because HUD is using the chronic homeless playbook for families,” says Smith. “It works for single adults but not for the population of families we are serving.” He believes the problem is not that HUD is pushing rapid re-housing but rather that it is dictating that jurisdictions, and ultimately providers, must serve families with the most barriers first because that is what worked on the single adult side.

“Family homelessness is a complex issue,” Smith continues. “HUD thinks the way they did it with singles is the answer. If it were as simple as one solution for everyone, we would have fixed homelessness a long time ago.”

In Massachusetts, rapid re-housing did not work for the Rivera family—a two-parent household with four children served by HAP Housing, which operates a rapid re-housing program in Springfield, MA, a city of about 150,000 in Western New England. After getting placed in rapid re-housing after a few months in shelter, their stabilization case manager at HAP Housing soon discovered there were underlying mental health and substance abuse issues, and she had serious concerns about the welfare of the children.

“Knowing the barriers that the family has encountered in the past with being rapidly re-housed and the potential dangers that the children faced without supervision from agency staff, it is clear that this family needs a more supportive environment that will help meet their mental health, substance abuse, and child welfare needs,” according to information provided by HAP Housing. The family is back in shelter.

Considering Local Factors

Comparing rapid re-housing programs across different communities is difficult because they can be tailored to suit local needs while still keeping to HUD’s core funding criteria. Oliva acknowledges that there is a wide variation in project models from community to community. “Rapid Housing in San Francisco or Los Angeles is not going to look the same as in Omaha. What is really, really important is that there is a housing search and placement component inside of any rapid re-housing program. Sometimes, rapid re-housing can serve as a bridge until other subsidies and programs are put into place for the family,” she says.

Many programs appoint housing navigators, who work directly with families to assess their needs and with the landlords to find suitable properties. It is important for those navigators to know what barriers the family faces, if, say there is poor credit or a criminal background, or some health issues that have not been addressed, according to Ann Linkey, division manager, homeless and rental counseling/supportive housing at Tabor Community Services, which runs the STIL program in Lancaster, PA. Then, the navigator can then talk intelligently and proactively with the landlord.

In Omaha, NE, Heartland Services runs rapid re-housing in a three-county metro area that includes Polk County, Iowa. In the early days, when they received their first HPRP grant, the programs struggled to help their families find appropriate housing and to keep clients housed. Since then, they have realized they needed to provide more intensive case management services up front.

“We have been a lot more successful after adding a housing advocate position,” says Rehousing Director Jody Jackson. Their average length of stay in rapid re-housing is about five months with a maximum of 12 months, and they are placing people in permanent housing, on average, in about 40 days. She would like to see them get that period below 30 days. Her most recent quarterly data shows that about 90 percent of the people who exited rapid re-housing a year ago had not returned to a shelter.

But, as in most communities, there is no way for Jackson to know if someone moved out of town or doubled up with relatives. “We know they did not turn up homeless again. Unfortunately, we do not have resources to follow up with people. That is one of the flaws with it.”

In Houston, which received the highest HUD score of any COC that applied for Tier 2 funding in Fiscal Year 2015–2016, the move to rapid re-housing has involved many moving parts and some missteps along the way. In the beginning, when they first received HPRP stimulus funds, the programs were run in a piecemeal fashion, with four different entitlement jurisdictions that “really did not talk to each other,” says Thibaudeau of Houston’s Coalition for the Homeless.

It took “a lot of tough meeting and working together” for all the jurisdictions within the Continuum of Care to resolve the chaos. “We came together and aligned our funding under common standards and business rules.” Thibaudeau concedes they “probably underestimated how tough it would be to implement a rapid re-housing program. As we often say to each other when we get really frustrated, we are the ones with an office and roof over our heads. We are not the ones in crisis or in a state of shock. We should be the ones doing the heavy lifting.”

Since January 1, 2015, every homeless candidate for rapid re-housing in the Houston metro area talks first with a neutral assessor, who runs them through the same sets of questions in order to determine whether someone should be referred for long-term permanent supportive housing or rapid re-housing. “We were really able to make sure that those who did not need long-term services and subsidies but have a lot of needs, including zero income, were guaranteed to get served. We standardized how all case managers act and really brought it to a system level.”

Houston’s Coalition for the Homeless also considers good landlord relations so critical that they regularly host “landlord appreciation” events and legal clinics to attract them to meetings. The city has established a system-wide landlord marketing group, where all the communications people from all the organizations speak with one voice to recruit landlords. “We do not talk about the family’s needs. We talk about the landlord’s need to have income,” says Thibaudeau.

When Will Evans, vice president of housing and supportive services at Community Connections in Jacksonville, FL—a city of almost 870,000 at the northern tip of the state—started converting over to rapid re-housing, he had already established a strong network of some 60 landlords from his days of running scatter-site transitional housing. He got their support by literally pounding the pavement. “I had to go out to the churches and say, ‘I am trying to end homelessness. If any of you are landlords, raise your hands.’”

Evans recently calculated that families in his city needed to make $19.76 an hour in order to afford the median rent for a two-bedroom apartment. The average wage in Jacksonville? About $8 an hour. Taking inspiration from programs he has seen up North, he proposed that some families—who have been rapidly re-housed for six months but have not made sufficient progress toward self-sufficiency—share the rent on a home with another homeless family. The idea does not sit well with everybody, but it has worked out well for a few families so far. “It is better to share a house than to be homeless,” he says. “No one is saying it has to be permanent.”

Programs Struggle Without Available Housing

Even good relationships with landlords do not solve the affordable housing crisis in many communities. A 2015 report from the Urban Institute on rapid re-housing noted that most evidence shows that the programs do help families exit homeless shelters, with low rates of return to shelter. By the same token, it said, rapid re-housing does not cure the long-term problem that plagues many communities: a lack of affordable housing. “After families exit rapid re-housing they experience high rates of residential instability. Many move again or double up within a year and face challenges paying for rent and household necessities.”

In Washington, DC, a shortage of affordable housing is putting a strain on rapid re-housing efforts. “The barriers that some of our families have, whether it is for lack of credit, poor credit, evictions, lack of income, make it harder for a landlord to want to work with our clients when they can get someone who is a market rate renter,” says Allison Tucker, rapid re-housing manager at the Department of Human Services for the District of Columbia.

Housing attorney Max Tipping, an equal justice fellow at the Washington Legal Clinic for the Homeless, says his client families in rapid re-housing often find themselves in poorly maintained units. “All these families are being driven into the subprime rental market, where all the units are in poor shape.” He says one of his clients has filed a complaint against a rapid re-housing landlord because he originally quoted the rent at $1,000 per month and then raised it to $1,350 when he learned she was in the rapid re-housing program. He says the landlords “know the city is desperate and they are upcharging to rent these out.”

Across the country in Los Angeles, the housing market is similarly tight. “In Los Angeles, the vacancy rate is less than two percent and it is not uncommon to find homeless families living in their vehicles,” says Katie Hill, deputy CEO of PATH Beyond Shelter in Los Angeles. “Even when families get vouchers for Section 8 subsidized housing, it is often impossible to find them an apartment.”

Los Angeles County uses a coordinated intake and assessment system, called the Homeless Families Solution System, where providers work closely together to identify resources for homeless families that go beyond rapid re-housing, such as permanent supportive housing. The system allows for “unprecedented information sharing and collaboration along different areas of Los Angeles County,” she says.

“You really have to look at a rapid re-housing program as something that is customized,” says Hill. That means having service providers who are able to look closely at each case and “do whatever it takes” to get the family stably housed. “Sometimes it is worth giving rapid re-housing a shot—even for high barrier individuals,” says Elizabeth Heger, PATH’s director of family programs.

Overall, Heger and Hill say, rapid re-housing has been a success. A year after leaving the program, they have found over 90 percent of families stayed housed—meaning they did not show up at another Los Angeles shelter.

Best Practices Matter

While rapid re-housing programs may differ widely in their details, administrators cite best practices that are key to success. They include: a centralized, community-wide intake program, client-centered case management with an array of services that are tailored to each family; a network of community partnerships with government agencies and nonprofits, strong relationships with local landlords, and workforce development services.

“To do rapid re-housing well, you have to be a lot more nimble and a lot more creative,” says Joyce Lavery, CEO and executive director of Safe Haven Family Shelter in Nashville, TN. “You have to keep up with families and customize services.”

“For us and others who have found rapid re-housing very successful, it is not housing only,” she asserts. Rather, she says, families “have the autonomy and dignity to make certain choices without a shelter staff dictating what they are.”

Safe Haven clinical supervisor Hannah Evans cites the success story of a high-barrier, two parent family with one child at home and another on the way. Five of their previous children had been taken into protective custody because of some concerns about abuse and neglect, and they had problems with past rental arrears.

Despite those issues, in less than two weeks, Evans had moved them into an apartment with community rapid re-housing funds. Once they were housed, they were able to work with the couple on their parenting skills. She found a nurse to help the mother bond with her new baby through breast feeding. The husband is now seeking full-time employment and they have joined a local church. Safe Haven also helped them secure a Section 8 voucher. “To keep a family in a shelter that has that much trauma is not always helpful, even in a wonderful shelter like ours,” says Lavery. “If you can get them into a permanent home where they can act as a family, it is undeniably a healthier alternative.”

Workforce development is an important component of many rapid re-housing programs. At Building Changes in Seattle, which funds rapid re-housing in three Washington counties, “one of the things we do is we identify new and emerging best practices that show promise to improve services for homeless families,” says associate director Nick Codd.

For a rapid re-housing pilot project in King County in Fiscal Year 2014–2015, Building Changes paired the short-term subsidies and case management of rapid re-housing with employment navigation services. “We felt that rapid re-housing is most successful when you are focusing not just on getting people housed, but making sure they have the income needed to support the housing,” says Codd.

By most accounts, rapid re-housing certainly does not end poverty as we know it, but rather ends an instance of homelessness, and is sometimes the beginning of families getting back on their feet. In Washington, DC, Tytianna Douglas had no family to turn to for help when she became homeless two years ago. The 24-year-old single mother, who had aged out of foster care, got placed in a Day’s Inn motel for a year with her kids. Then, she heard about the rapid re-housing program, and Douglas, who was pregnant with her daughter at the time, managed to get a two-bedroom unit where she pays $118.40 per month. Her now year-old daughter is in day care, while she works a part-time, minimum wage job as a hostess.

After a succession of less than satisfactory case managers, who, Douglas says, mostly just asked her about her budget and collected her rent once a month, she finally has landed on one she can really talk to and is receiving help connecting her with the services she needs.

“At the moment, me and my children are housed, so I cannot complain,” she says. “It is not permanent, so you got to think ahead. Sometimes, it can be overwhelming.”