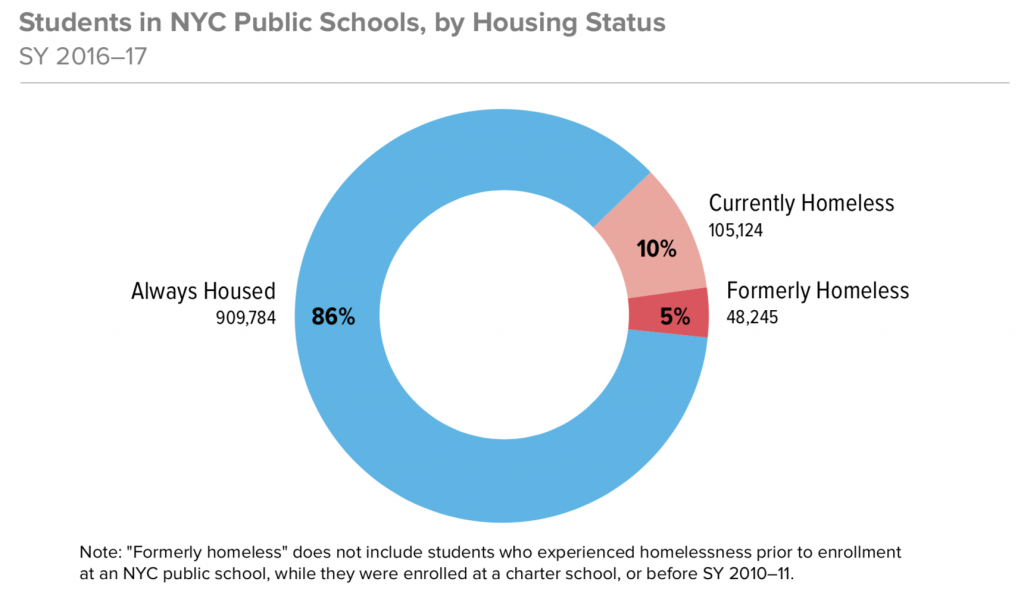

Homelessness disrupted the education of approximately 105,000 New York City public school students in the 2016–17 school year. Unfortunately, for many of these students, the effects of this instability will last long after they have moved to permanent housing. School instability factors such as chronic absenteeism and mid-year transfers—prevalent among currently homeless students—remain high after these students are housed. Perhaps as a result of this lingering school instability, formerly homeless students continue to struggle academically and score lower than their housed classmates on state exams.

The effect of experiencing homelessness will follow these students as they transition to middle or high school, and may define a significant portion of their academic career. Preventing the lingering impact of instability requires that students be identified and engaged with services not only while they are currently homeless, but immediately upon being rehoused.

KEY TERMS

Currently Homeless

Students who were identified at any point during SY 2016– 17 by the New York City Department of Education as meeting the McKinney-Vento definition of homelessness, which includes students in shelter, doubled-up, in hotel/motels, awaiting foster care, or other temporary arrangements.

Formerly Homeless

Students who were not identified as homeless during SY 2016–17 but had been homeless at some point since SY 2010–11.

Always Housed

Students who have never been identified as homeless between SY 2010–11 and SY 2016–17.

This report is a part of the Student Homelessness in New York City series. This series uses the most recent year of data available (at the time of publication, the 2016–17 school year) from the New York City Department of Education to explore issues affecting students experiencing homelessness, including the geography of homelessness, the prevalence of school instability factors like chronic absenteeism and mid-year transfers; whether the additional education needs of language learners and students with special education needs are being met on time, among other topics.

School Instability Outlasts Housing Instability

In SY 2016–17, there were over 48,000 housed students who had been homeless at some point during the previous six years. Even though these students were no longer facing the day-to-day uncertainty of homelessness, they continued to feel the aftereffects of this experience and to face a heightened risk of school instability factors such as chronic absenteeism and mid-year transfers.

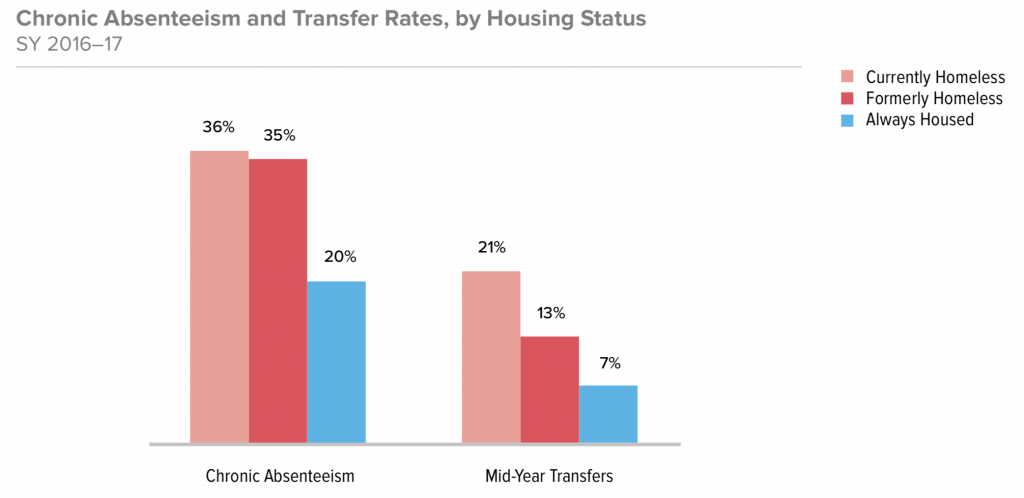

Regular school attendance remained a challenge for students who had previously experienced homelessness, with chronic absenteeism rates comparable to their classmates who were still homeless (35% vs. 36%, respectively)—over 1.5x the 20% rate for students who were consistently housed.

Similarly, while not as likely to transfer schools as their homeless classmates (21%), in SY 2016–17 formerly homeless students transferred schools mid-year at rates almost 2x as high (13%) as their never homeless peers (7%).

KEY TERMS

Chronic Absenteeism

Missing more than 10%, or more than 18 days, of a 180- day school year.

Mid-Year Transfers

Students who transfer from one school to another at any point during the school year.

For many students, both entering and exiting homelessness can require moving between neighborhoods or boroughs. Although the McKinney-Vento Act protects formerly homeless students’ right to continue attending their school of origin, these new commutes may be unmanageable and necessitate that students transfer schools yet again.

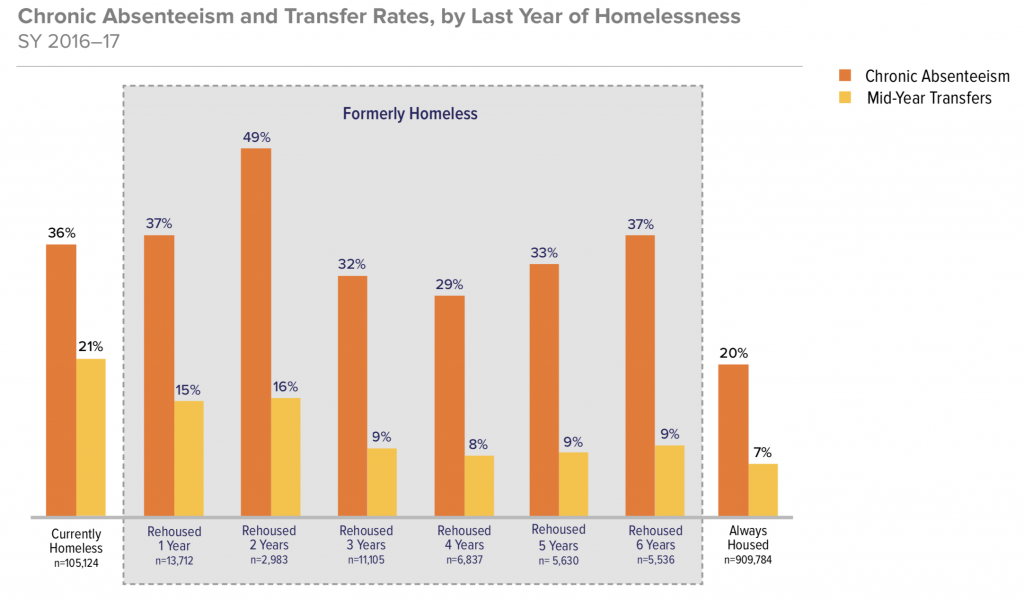

The Lasting Effects of Instability

When examining available data for the six year period from SY 2010–11 to SY 2016–17, students who were housed in SY 2016–17 but had experienced homelessness at some point since SY 2010–11 had considerably higher rates of chronic absenteeism and school transfers than their classmates who had never been homeless. Even among students who experienced homelessness in SY 2010–11 but were housed throughout the following six years, the educational repercussions that often occur with homelessness continued to be seen.

Chronic absenteeism rates for formerly homeless students fluctuated between

a high of 49% for students who had been rehoused for just two years, and a low of 29% for students who had been rehoused for four years. Even after being re-housed for six years, formerly homeless students were chronically absent at a rate similar to that of currently homeless classmates (37% and 36% respectively), and more than 1.5x that of housed but never homeless students (20%).

Once rehoused, transfer rates for formerly homeless students were consistently lower than for their currently homeless classmates (21%). Among formerly homeless students, transfer rates were the highest during the first two years of moving into housing (16%) and decreased after that, plateauing at 9%—a slightly higher rate than for their housed but never homeless peers (7%).

Despite a return to housing, formerly homeless students continued to experience instability at rates significantly higher than their housed classmates. This suggests that homeless students experience factors that impact their education beyond the lack of a permanent address— family instability and violence, lack of sleep, food insecurity, physical and mental health challenges, lack of appropriate childcare, financial insecurity— and that services beyond housing assistance may be necessary to erase the impact of homelessness.

The Lasting Effects of Homelessness on Academic Outcomes

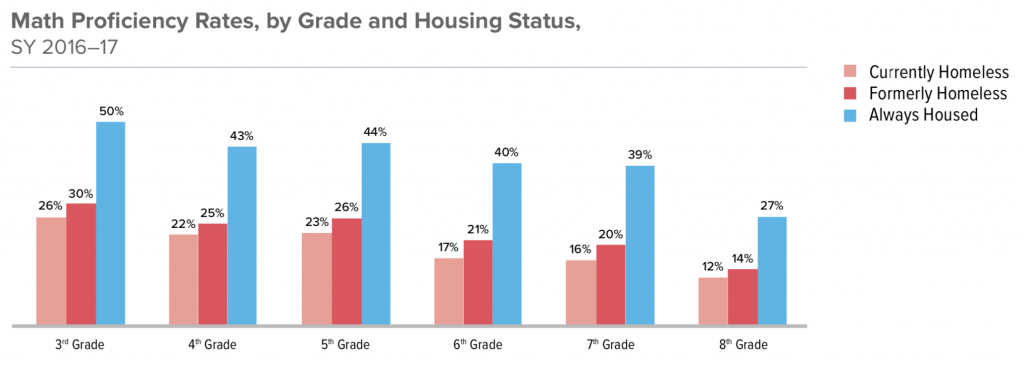

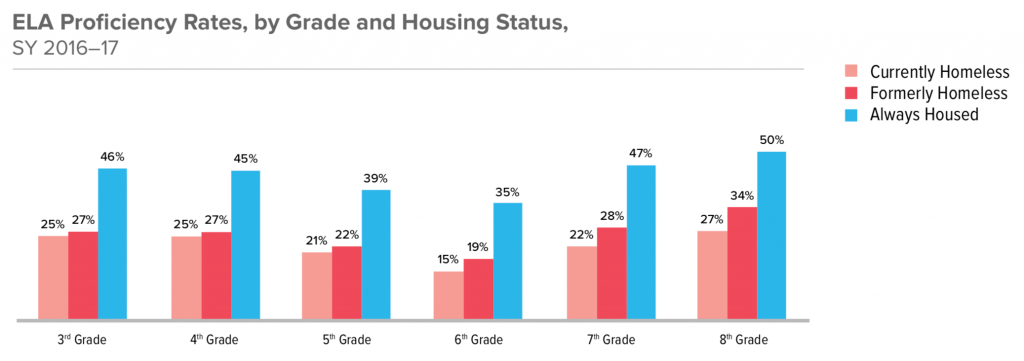

Not attending school consistently and transferring schools mid-year can make it harder for formerly homeless students to keep pace academically. While these students were more likely than their homeless classmates to score proficient on their annual statewide assessments, they scored significantly lower than their always-housed peers. Across grades, always-housed students scored proficient at rates 1.5x to 2x higher than formerly homeless students.

Regardless of housing status, proficiency rates decreased as grade level increased with third graders being roughly 2x as likely as eighth graders to score proficient on the math exam. Nevertheless, across all grades proficiency rates for formerly homeless students were just between 2 and 3 percentage points higher than for their currently homeless classmates (30% vs. 26% in third grade, and 14% vs. 12% in eighth grade). In comparison, for students who were always housed, 50% scored proficient in math in third grade and 27% scored proficient in eighth grade.

As with math assessments, ELA proficiency rates for formerly homeless students were closer to their currently homeless classmates than to their always housed peers, regardless of grade. Among third graders, 27% of formerly homeless students scored proficient in ELA, compared to 25% of currently homeless and 46% of their always-housed classmates.

One way to know how well students are progressing is through the annual statewide assessment exams on math and English Language Arts (ELA). If students are able to score a 3 or above on the 4-point scale, they are deemed proficient, or to be performing at their grade level.

The Importance of Offering Continued Support to Students that Experience Homelessness

Many of the challenges that students experience while homeless linger long after the day-to-day uncertainty of their housing situation comes to an end. Currently housed students who have experienced homelessness continue to experience school instability at rates similar to their currently homeless classmates. They are also more likely to underperform academically and score lower on state assessments than their housed peers who have never experienced homelessness. Even after being rehoused for six years, these students never fully bounce back and continue to experience the negative impacts of housing instability.

Identifying formerly homeless students can prove challenging, especially if they transfer schools after becoming housed. These students may be reluctant to tell teachers and school staff about a prior episode of homelessness, which can prevent them from receiving the help and attention they need to overcome the aftershocks of their previous homeless experience. Additionally, even if successfully identified, formerly homeless students would not be eligible to receive the McKinney-Vento supports available to their homeless classmates.

It is imperative to identify and support students while they are homeless to minimize the negative and long-lasting effects of housing instability. Likewise,

it is key that this support continues as these students transition out of homelessness and into more permanent housing, so that their past history of housing instability does not negatively affect their future academic performance.

Click for more information on McKinney-Vento.

Ralph da Costa Nunez, PhD, President and CEO

Aurora Zepeda, Chief Operating Officer

Project Team:

Andrea Pizano, Chief of Staff

Josef Kannegaard, Principal Policy Analyst

Rachel Barth, Senior Policy Analyst

Kaitlin Greer, Policy Analyst

Katie Linek Puello, Content Manager

Hellen Gaudence, Senior Graphic Designer