August 2018

Executive Summary

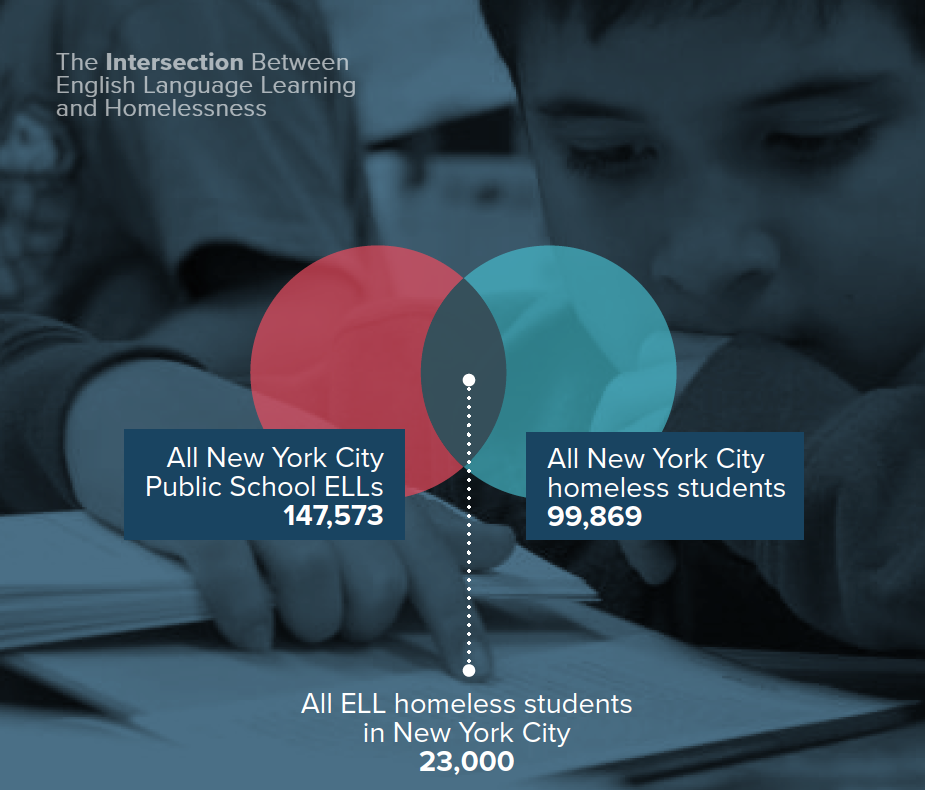

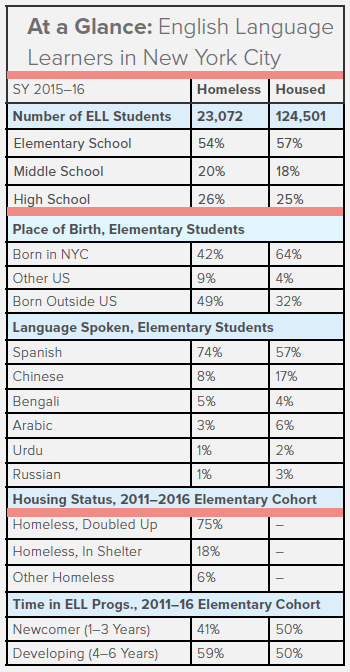

English Language Learners (ELLs) make up roughly one in every seven students enrolled in New York City public schools each year. Homeless students are a growing share of this group, increasing by more than 50% in six years. By SY 2015–16, one in six English language learners was homeless, a total of 23,000 students.

In the midst of these skyrocketing numbers, and especially at a time when there is a fresh perspective brought to New York City Public Schools by a new Chancellor, now is the time to ensure that the needs of these homeless children are part of the conversation about how schools can best identify, serve, and be accountable to ELLs.

English Language Learners in New York City public schools are a diverse group. They speak over 160 languages other than English, and roughly half are born outside the United States. Overall, 51% of elementary ELLs were newcomer, learning English within three years of starting Kindergarten.’

While homeless ELL students must overcome many academic hurdles, the data in this brief show that when children learn English early, within the first three years of their education, they perform as well as or better than their classmates who already know English when they start school. For elementary students who are learning English, becoming fluent within the first few years of their education means they are more likely to score proficient on State ELA or math assessments and less likely to be held back a grade.

This early fluency also benefits the city’s bottom line—in SY 2015–16 alone, taxpayers could have saved $1.7 million on additional education for developing ELL students who took more than three years to learn English. Avoiding these costs and setting these students on a positive educational path should be paramount to the New York City Department of Education’s (DOE) agenda for ELL students.

Newcomer ELLs: Achieve English fluency in 3 years or fewer.

Developing ELLs: Achieve English fluency in 4 years or more.

Homeless, Doubled Up: Students who live with another family or with friends due to economic hardship.

Homeless, in Shelter: Homeless students who live in a New York City homeless shelter.

Other Homeless: Students who lived somewhere not meant for habitation, such as a car or outdoors.

New York City’s English Language Learner Program

More than 15,000 Kindergarten students in New York City Public Schools are designated as English Language Learners (ELLs) each year. Schools use a home language questionnaire, in-person interview, and/or standardized test score results to determine whether non-native-English speakers require additional language learning supports. Every student who is identified as an ELL is entitled to placement in English as a New Language classes or bilingual education programs, including Dual Language and Transitional Bilingual Education programs. Once determined to be an ELL, these students are assessed every year to determine if they have achieved fluency in English.

Key Findings

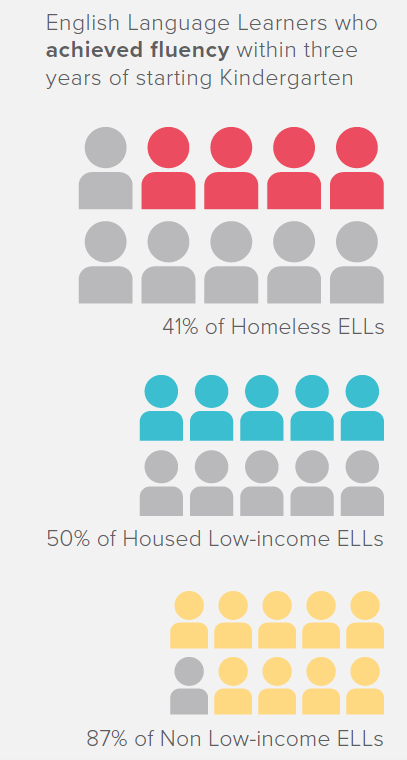

- Homeless ELLs in elementary school are less likely to achieve fluency within three years compared to their low-income housed classmates (41% to 50%).

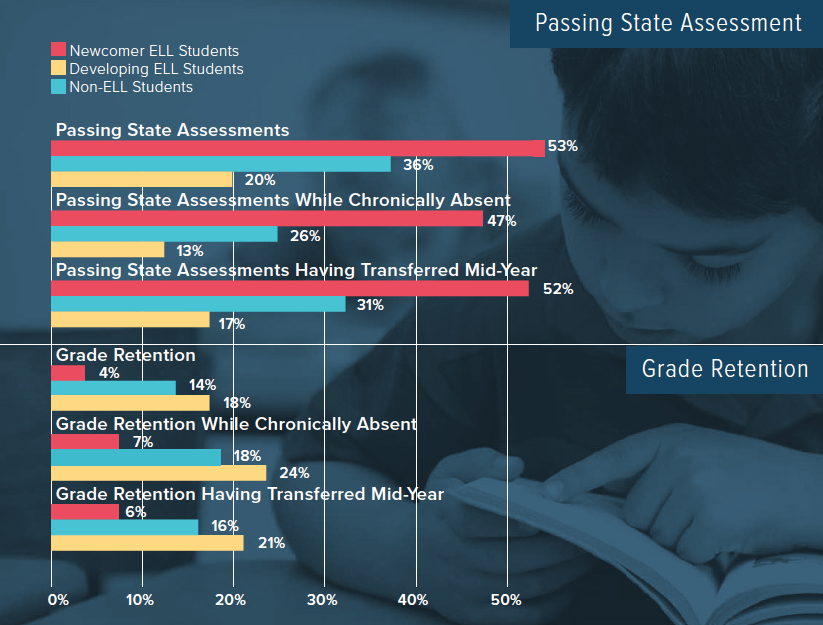

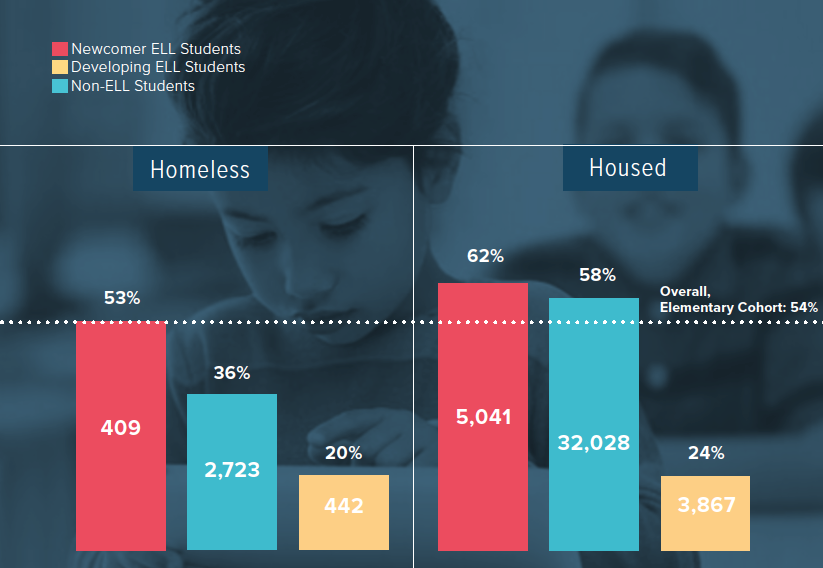

- Among homeless students, newcomer ELLs perform better on fifth grade assessments than both their developing ELL and non-ELL peers (53%, 20%, and 36%).

- Even among homeless students who face mid-year school transfers or absenteeism, newcomer ELLs excel academically. Those with a history of chronic absenteeism are more likely to score proficient on their fifth grade State assessments than homeless students who were not ELLs or who were developing ELLs (47%, 26%, and 13%). The pattern holds for newcomer ELL students who transferred schools mid-year (52%, 31%, and 17%).

- Homeless ELL students are more likely than other homeless students to live doubled up. Among students in the 2011–2016 elementary cohort, nearly three-quarters (74%) of all homeless ELL students lived doubled up, while under half (44%) of all homeless students in the cohort were doubled up.

Note: Cohort used in this report uses data from SY 2010–11 to SY 2015–16 and includes students who were enrolled in New York City Public Schools all six years and started Kindergarten for the first time in SY 2010–11. Input variables including housing and income status, chronic absenteeism, and mid-year transfers were looked at over the first three years of school for the elementary cohort (SY 2010–11 to SY 2012–13). Outcome variables including newcomer/developing ELL status, State assessment proficiency, and grade retention were over the final three years of our data (SY 2013–14 to SY 2015–16). Percentages may not add to 100% due to rounding.

Homeless ELLs Take Longer to Become Fluent

ELLs experiencing homelessness take longer to learn English than their housed peers, on average. In the 2011–2016 elementary cohort, 41% of homeless ELL students reached fluency in English within three years, compared to 50% of low-income housed students and 87% of non-low-income housed students.

As difficult as it is for all ELL students experiencing homelessness to become fluent in English, Spanish speakers face the most challenges. They are the least likely to be newcomer ELLs—among the cohort, only 39% were fluent in English within three years, compared to 53% of homeless children who speak other languages.

Homeless Student Outcomes

Newcomer ELLs and Developing ELLs vs. Non-ELLs

Homeless newcomer ELL students who learn English within three years of starting Kindergarten perform better academically over time when compared to homeless students who are developing ELLs or never ELLs.

Learning English Quickly Facilitates Academic Success

State Assessment Proficiency, by Years in ELL and Housing Status

Newcomer ELLs are better off academically than their peers, on average. This pattern is true for both homeless and housed students, as early fluency can help students pass State assessments and be promoted to the next grade.

Among homeless students, newcomer ELLs performed much better than their non-ELL or developing ELL classmates on fifth grade State assessments—53% compared to 36% and 20% respectively.

Newcomer ELL students who were homeless were also less likely to be held back than their homeless peers who were not ELLs or who were developing ELL students (4%, 14%, and 18%).

Homeless Newcomer ELLs are Academically Resilient

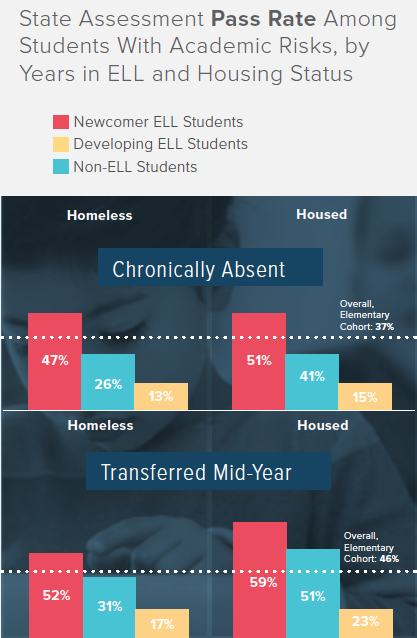

Homeless students are more likely than their housed peers to be chronically absent and to transfer schools mid-year. This heightened classroom instability can often mean that homeless students fall behind academically. However, homeless newcomer ELL students excel academically even when they are chronically absent or change classrooms.

Chronically absent newcomer ELLs in the 2011–2016 elementary cohort who were homeless exceeded the State assessment proficiency rates of homeless non-ELLs and developing ELLs with similar absenteeism (47%, 26%, and 13%). These students were also held back at lower rates (7%, 18%, and 24%).

Among homeless students who transferred mid-year, similar trends surface. Newcomer ELL students scored higher on State proficiency assessments (52%, 31%, and 17%) and were held back less often (6%, 16%, and 21%) compared to homeless non-ELLs and homeless developing ELLs.

Next Steps

ELLs and homeless students face academic challenges,

such as identification and access to programs. Data show

that homeless ELL students who receive consistent services

at an early age outperform their peers academically.

- The needs of more than 23,000 homeless ELL students must be included in this planning as the New York City DOE is in the midst of broad ELL reforms. These reforms are calling for universal bilingual services for all ELL students and allocating $40 million towards additional resources in SY 2016–17.

- Homeless students and ELLs are often considered as distinct groups by New York City public schools. However, as the two groups overlap significantly, it is critical to eliminate barriers between programs that serve these homeless students and ELLs through clear, consistent data sharing and communication between schools and departments.

- Increasing outreach to non-English-speaking homeless families in their native languages and connecting them with early, consistent ELL services must be a priority.

- Homeless shelters and community agencies can support homeless students through housing transitions and mid-year school transfers by ensuring that they are immediately placed in appropriate ELL programs upon transferring schools and receive consistent services.

- Doubled-up ELL students require a different outreach approach than other homeless students. Communication and partnerships between teachers, parents, school liaisons, and shelter and community-based organizations are key in both identifying and serving these students.

SOURCE: New York City Department of Education, unpublished data tabulated by the Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness (ICPH), SY 2010–11 to SY 2015–16.

Ralph da Costa Nunez, PhD, President and CEO

Aurora Zepeda, Chief Operating Officer

Katie Linek Puello, Digital Communications Manager

Project Team:

Anna Shaw-Amoah, Principal Policy Analyst

Amanda Ragnauth, Senior Policy Analyst

Kristen MacFarlane, Senior GIS Analyst

Kaitlin Greer, Policy Analyst

Hellen Gaudence, Graphic Designer