Introduction

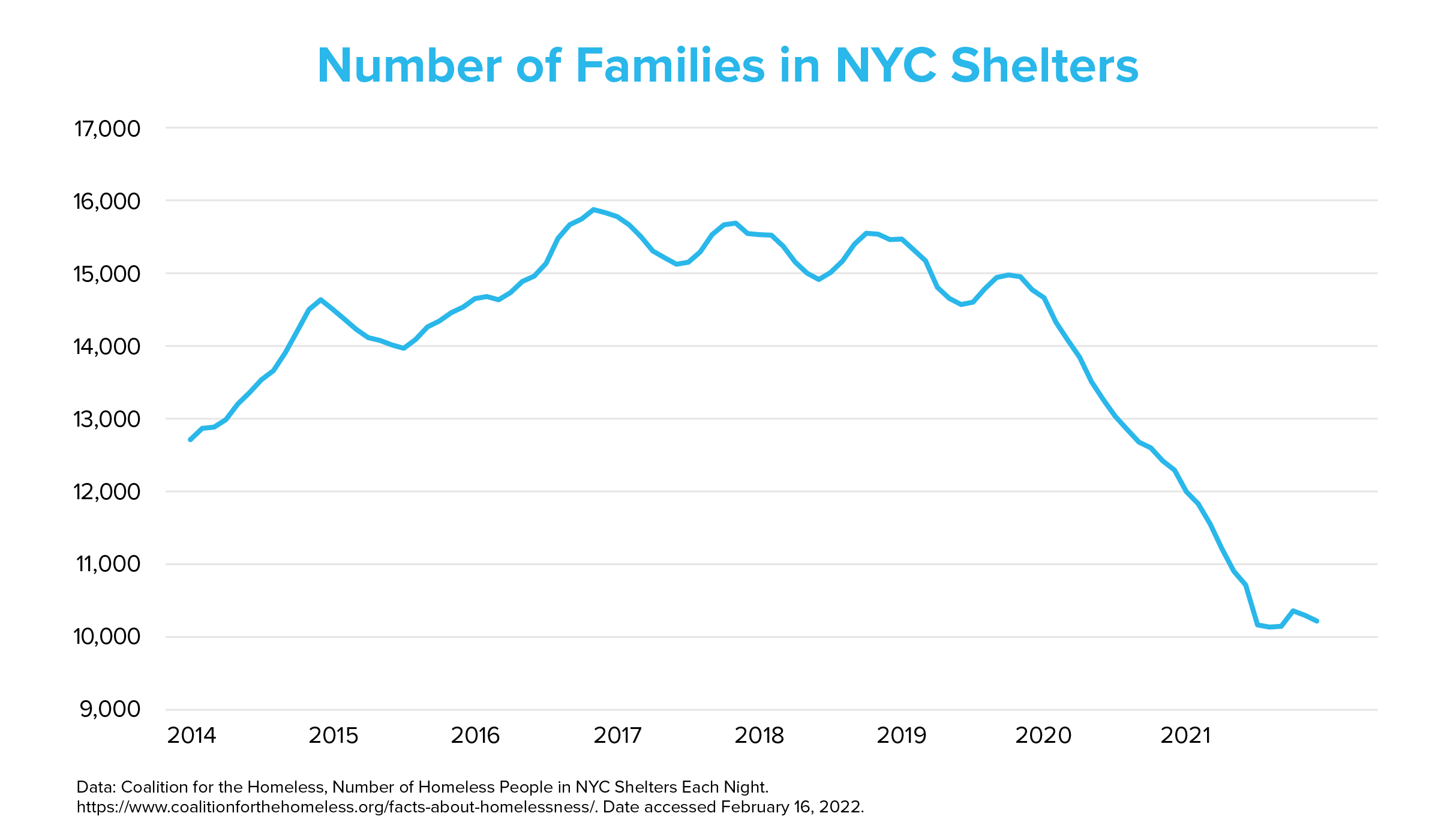

Confronting New York City’s family homelessness crisis was a challenge for Mayor Bill de Blasio. When his term ended in December 2021, the number of families experiencing homelessness was lower than it had been at the start of his tenure—though this is no doubt due, in part, to the eviction moratorium put in place as an emergency response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Finding a long-term solution to family homelessness has been impossible for all the City’s recent mayors: from reliance on temporary vouchers, to the expense of constructing affordable housing, to the myriad needs of families in shelter, mayors have faced roadblocks to reducing the family shelter census and addressing the root causes of homelessness.

Unlike any other city in the United States, New York City maintains a universal “Right to Shelter” for all people experiencing homelessness.1 In the early 1980s, the City, under pressure from Steven Banks of the Legal Aid Society, who would later play an important role in the de Blasio administration, agreed to a series of court settlements that cemented this right. More than 35 years later, the city government’s legal obligation to provide shelter for homeless families remains, but efforts to do so have undergone a dramatic process of institutionalization and investment. Family homeless shelters have evolved, multiplied, diversified, and become an inextricable part of the City’s network of social welfare services. And yet, despite the hundreds of millions of dollars the City spends each year on this challenge and the changes in how shelter is provided and families supported, family homelessness and poverty remain an intractable problem. On an average day in 2021, nearly 11,000 families with children lived in shelter—almost three times the figure in 1985.2

Even as the experience of homeless families in the shelter system has changed dramatically over the last several decades, the fundamental causes and challenges of family homelessness have remained the same: structural racism, generational poverty, disparities in educational and employment opportunities, domestic violence, and a lack of decent affordable housing options.

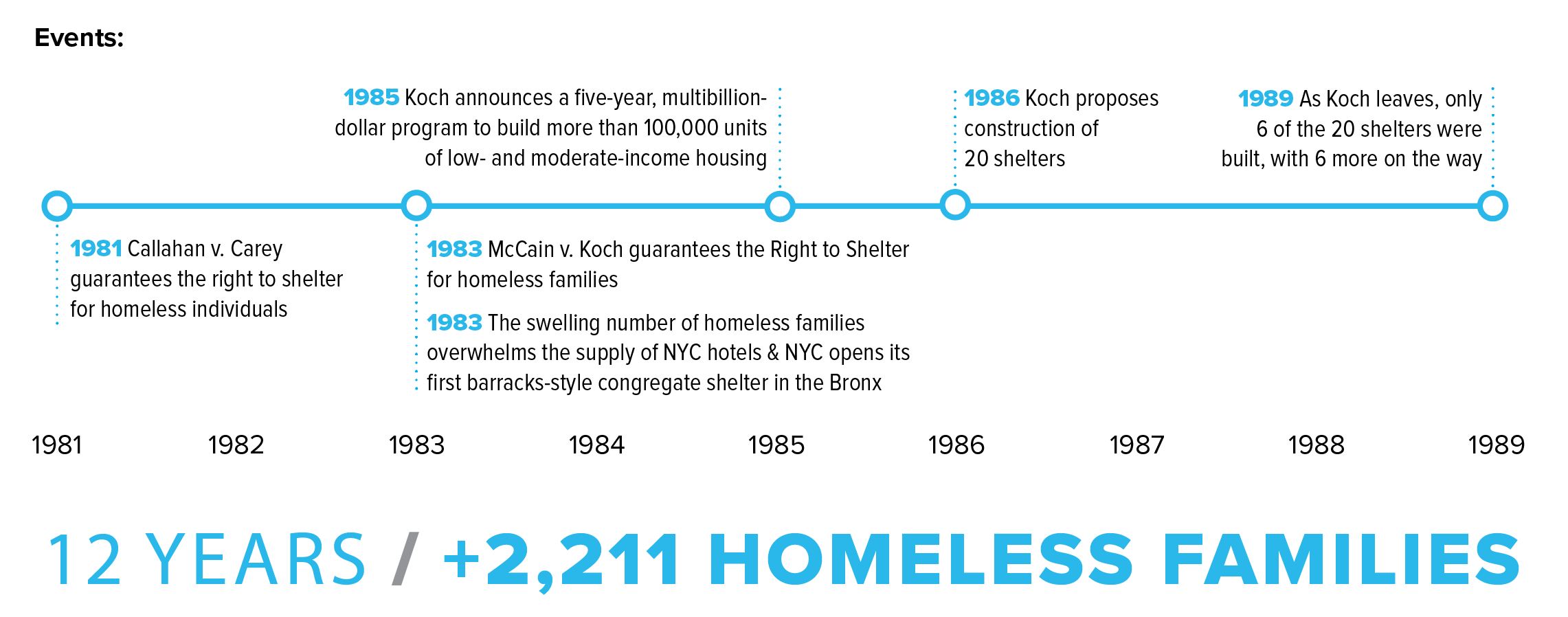

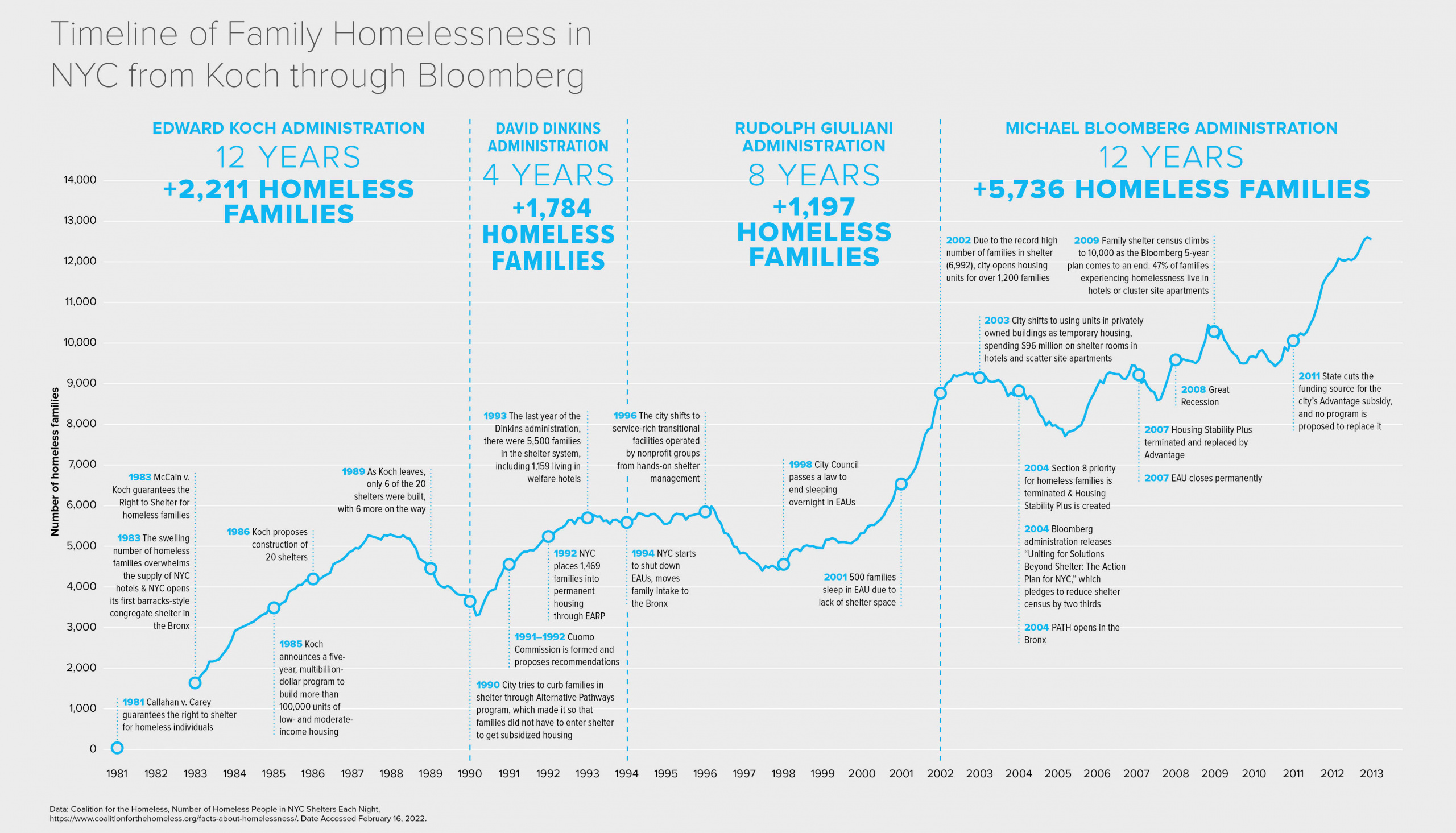

This three-section report will show how the last five mayors have contended with these interconnected challenges and seeks to contextualize the policies of the de Blasio administration on family homelessness. The first section consists of a timeline that summarizes each mayoral administration from Edward Koch to Michael Bloomberg and traces the growth of family homelessness and the development of the shelter system. The second section reviews the de Blasio administration as it sought to tackle family homelessness. The final section looks to the future of family homelessness in New York City under the new administration, led by Mayor Eric Adams.

Note: Citations and sources for data are included in the PDF version of this document available by clicking Downloads underneath the Table of Contents.

Historical Context: The Koch, Dinkins, Giuliani, and Bloomberg Administrations

Edward Koch Administration

From 1982 to 1987, the number of families in the city who were homeless increased from just over 1,000 to more than 5,000.3 Additionally, as a result of the class action lawsuit McCain v. Koch, families were granted a Right to Shelter, a policy that remains in place today.4

This rise in family homelessness can largely be explained by the economic recession of the early 1980s,5 which disproportionately impacted Black New Yorkers and those living in poverty.6 From the 1970s to the early ’80s, the poverty rate in New York City grew from 14.5 percent to over 25 percent. The recession also contributed to a significant shortage of low-income housing and cutbacks in social service spending.7 The dearth of affordable housing was due in part to federal funding cuts by the Ronald Reagan administration to national programs that supported its creation; now, local municipalities had to fund these initiatives with little federal help.

Koch’s initial approach to meeting the needs of the rising numbers of homeless families was to house families experiencing homelessness in existing City shelters and hotels (which came to be known as “welfare hotels”).8 Families seeking housing were referred by welfare centers to the Emergency Assistance Unit (EAU) in Manhattan, which placed families in hotels.9 The administration hesitated to spend money on long-term investments in shelters, in part because they believed that this increase in homelessness was temporary.10 This crisis-oriented response did little to address the root causes of the problem. Furthermore, it proved unsafe for families and expensive for the City.

As the number of families experiencing homelessness continued to increase, it became clear that this was more than just a short-term crisis. The Koch administration thus pivoted its approach and proposed the development of service-rich transitional shelters, which would become known as Tier II facilities. Tier II shelters would provide services such as job training and childcare to assist families in transitioning back to permanent housing. Koch also hoped to reduce homelessness by increasing the amount of affordable housing,11 a promise on which his and future administrations would struggle to deliver.

Before the 1980s, social services were generally enough to keep families housed. Comparatively few families were forced to apply for shelter options provided by the City and family homelessness was not an issue in the eyes of the public. By 1989, the end of Koch’s tenure as mayor, it was well within the public consciousness, and the City had begun to develop the programs it still runs today to confront family homelessness. Tier II shelters continue to provide housing and supports for homeless families in New York. Koch’s proposal for increased affordable housing, fulfilled to some extent by his successors, helped provide some housing for families experiencing homelessness.12

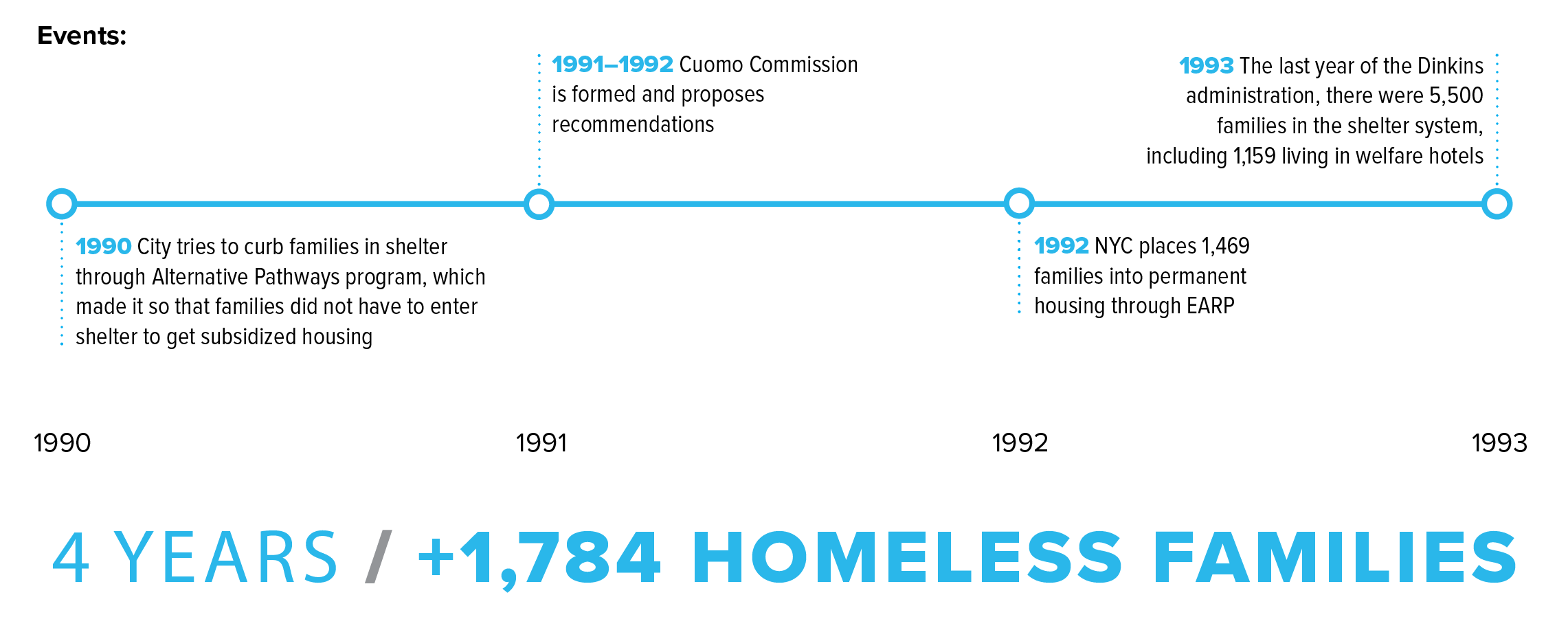

David Dinkins Administration

Before being elected mayor, David Dinkins criticized the Koch administration for its crisis-oriented approach to family homelessness, arguing that its continued reliance on welfare hotels for homeless families and efforts to expand the shelter system were misallocations of resources.13 Committed to placing homeless families in permanent housing, Dinkins built on Koch’s policies to create new housing units in City-owned buildings. In addition, he gave families in the shelter system priority to receive public housing placements and housing subsidies. The result was that in 1990, the first year of the Dinkins administration, over 4,400 families moved from shelter to permanent housing. At the same time, the Dinkins administration attempted to reduce the City’s reliance on welfare hotels to house families. Between 1990 and 1991, an average of around 350 families lived in welfare hotels each night, a decrease from an average of almost 1,900 in the final years of the Koch administration.14

However, high levels of poverty and unemployment lingered from the previous decade’s recession, continuing to drive families into homelessness. Eventually, the number of families entering the shelter system outpaced the administration’s ability to quickly move families into permanent housing.15 The shelter population increased, returning to the levels of the late 1980s. Dinkins announced that he was forming a commission of experts to provide a new direction for the City’s homelessness policy. The “Cuomo Commission,” as it came to be known, was headed by Andrew Cuomo, Governor Mario Cuomo’s son, and the leader of the transitional housing organization HELP USA. The commission (1) encouraged a shift from Tier I emergency congregate shelters to service-rich, not-for-profit operators; (2) recommended the creation of the Department of Homeless Services (DHS), a new, City agency independent from the Human Resources Administration (HRA); and (3) advocated for an increase in homelessness prevention, largely through investing in rental subsidies.16

During his time in office, Dinkins worked to create deep systemic change to curb the rise in families experiencing poverty and homelessness. However, due to the extremely high demand for family shelter, the number of families in the shelter system continued to increase. In the 1993 mayoral race, Dinkins was narrowly defeated by Rudolph Giuliani. Giuliani attempted to make social services more efficient by reducing the reliance on government assistance and promoting self-sufficiency through employment.

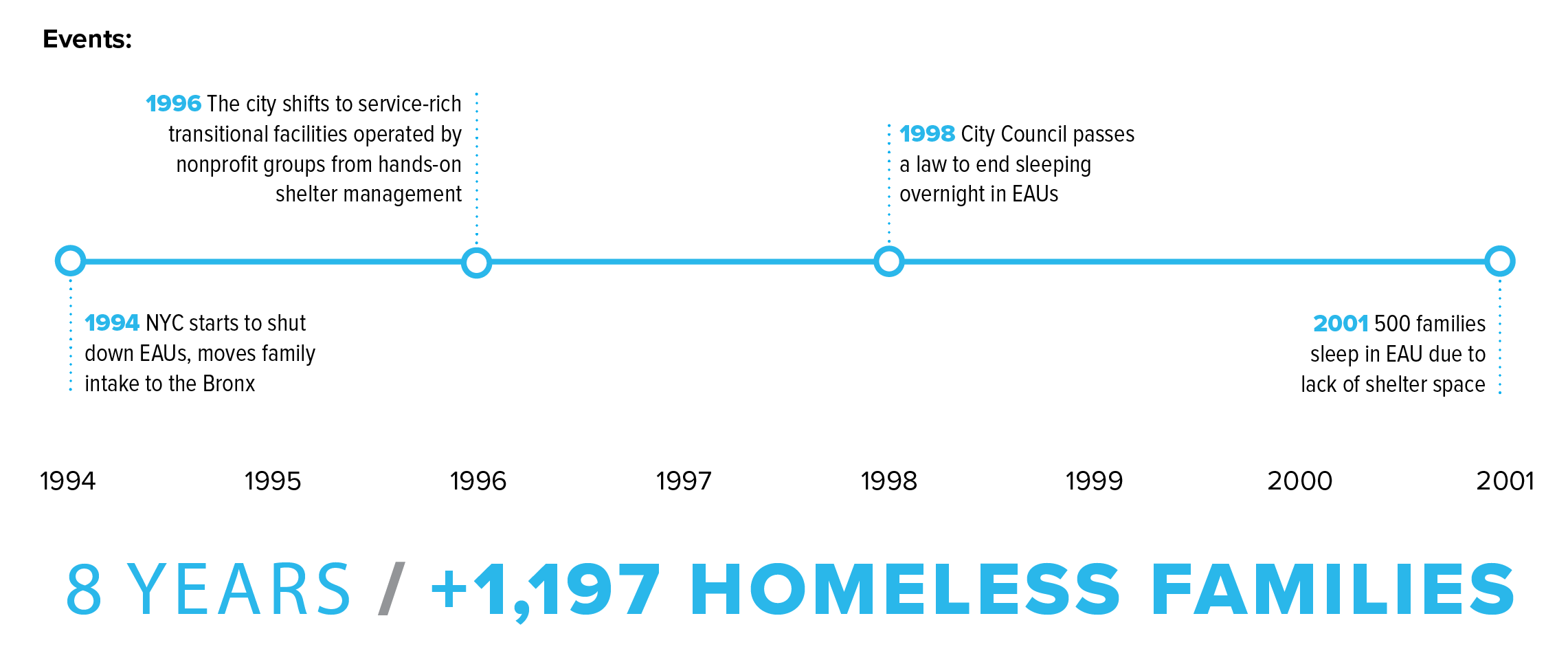

Rudolph Giuliani Administration

Giuliani criticized Dinkins during the 1993 campaign for failing to halt the increasing number of families experiencing homelessness, advocating for a stricter approach to social services.17

After he became mayor, in 1994, Giuliani began to cut the City social services budget. He also made it harder for families to be eligible for welfare, food stamps, and homeless shelters. The number of families denied entry increased by over 700 percent in just one year, from almost 900 in 1996 to over 7,700 in 1997. Around 14,400 families were rejected for placement in the shelter system in 1998. These changes reduced the number of families in shelter, from an average of 5,700 in 1996 to 4,600 in 1998, but did nothing to improve the lives of New Yorkers living in poverty.18 At the same time, Giuliani began the practice of placing families seeking shelter in “cluster site apartments.”19 Under this program, the City paid landlords to shelter individuals experiencing homelessness night by night, often without contracts.20 By doing so, the City was able to quickly expand its capacity to shelter families and comply with the Right to Shelter. This practice left families with fewer social supports and generally less safe living situations than nonprofit Tier II shelters provided. The use of cluster sites was supposed to be temporary but continued through the next two mayoral administrations. And despite their use, the reduction in the number of families in shelter proved temporary, as the numbers climbed again for the last few years of the Giuliani administration, from 1999 to 2001.21

Between 1995 and 1998, welfare and food-stamp caseloads declined by 30 percent. This decline, however, did not represent a reduction in the number of families who needed these benefits. Welfare applicants were often unjustly turned away when applying for social services.22

This effort to cut social services was part of a national movement of welfare reform. The Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act (PRWORA) was passed by the federal government in 1996 to end reliance on welfare and encourage employment. The act ended Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) and replaced it with Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF). TANF was time-limited—restricting an individual’s benefits to five years—and required that recipients be employed.23

The Giuliani administration actively worked to decrease the City’s role as a provider of social services, reducing costs for the City. However, these changes did not help low-income New Yorkers and, for the most part, made overcoming the challenges they faced more difficult.

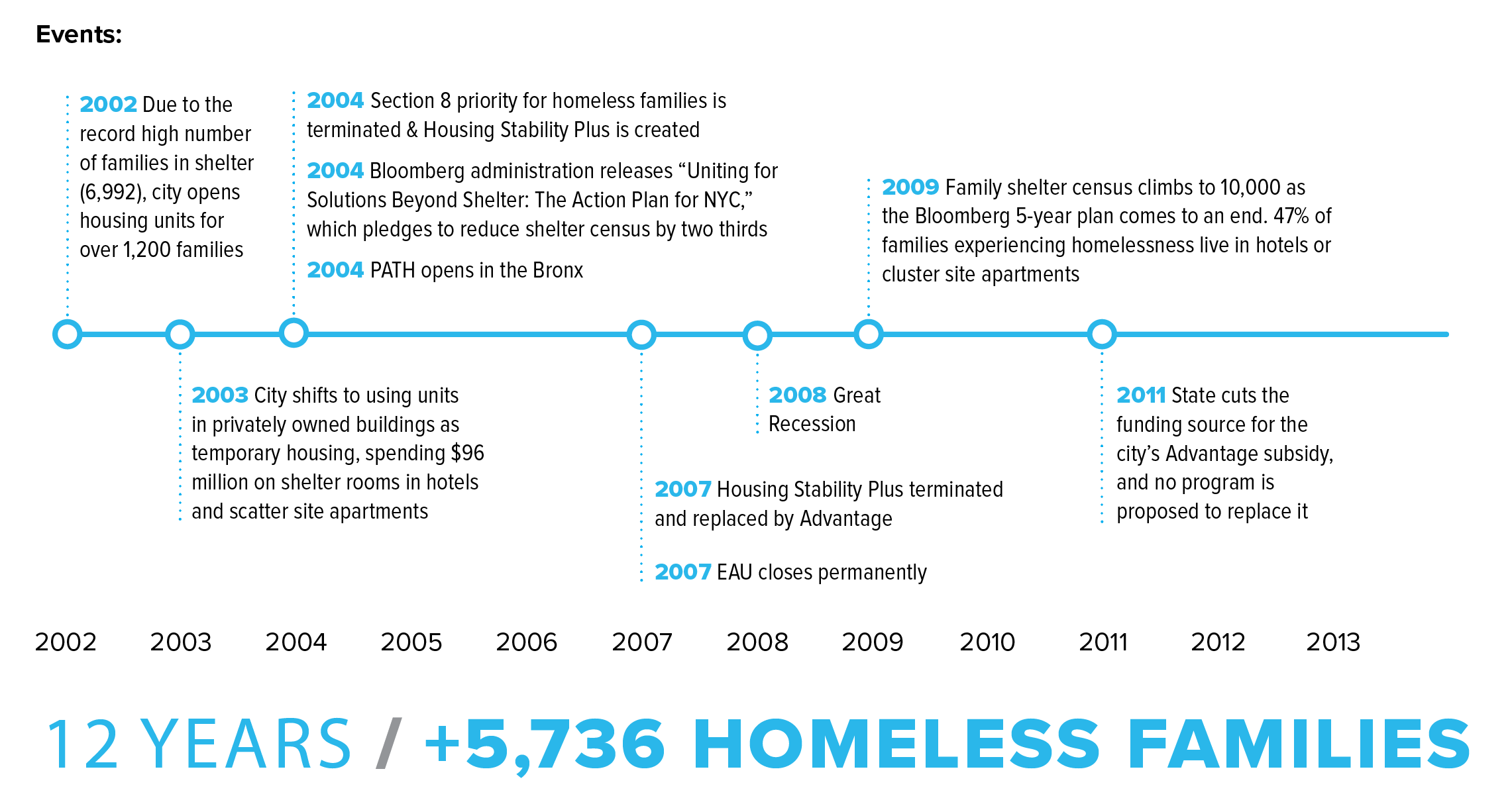

Michael Bloomberg Administration

There were close to 7,000 families in shelter when Bloomberg entered office in 2002. This number continued to increase to over 9,000 in 2003, creating a shortage of shelter space for families. Families were thus forced to sleep on the floors of the intake center for families—the EAU—while the City scrambled to find available shelter units. While the City continued to rely on the network of nonprofit transitional shelters, they also continued the practice of placing families in hotels, as well as moving families into cluster site apartments—which began under Giuliani.24 The administration also attempted to rapidly move more families into permanent housing by increasing the proportion of federal Section 8 vouchers available to homeless families. The number of families in shelter who moved into permanent housing went from just over 3,500 in Fiscal Year (FY) 2002, Bloomberg’s first year in office, to over 7,000 in FY 2004, with Section 8 and NYCHA placements accounting for more than 80 percent of those moves. These policies, along with improvements in the economy, allowed the shelter census to stabilize by 2004.25

In 2004 Bloomberg appointed a task force that produced Uniting for Solutions Beyond Shelter: The Action Plan for New York City and set the ambitious goal of reducing homelessness by two-thirds in five years. Bloomberg’s plan was largely centered around preventing homelessness by (1) increasing New York’s affordable housing stock, (2) bolstering programs that would keep families housed, and (3) attempting to minimize housing disruptions by rapidly moving families from shelter into subsidized permanent housing.26

To operationalize these goals, the Bloomberg administration introduced Housing Stability Plus (HSP) in late 2004. It provided nearly a quarter less rental support than Section 8, expired after five years, and automatically decreased by 20 percent each year under the assumption that families’ incomes would be increasing year to year. In 2007, the City replaced HSP with the Advantage New York program. Advantage gave families more money than HSP, but expired after only two years and had a low income ceiling, so that a family ran the risk of losing the subsidy if a parent found a full-time job. In 2011, Governor Andrew Cuomo cut the funding source for the Advantage program, and the Bloomberg administration did not find other funding or develop a different subsidy.27

After Advantage ended, the number of families in the shelter system spiked. Additionally, the time limits of the programs made it challenging to move families out of shelter. The shelter census reached 10,000 in 2009. And while the average length of stay in shelter decreased, data indicated that many families returned to shelter due to the limitations of the administration’s policies. All of this in tandem with the Great Recession caused the number of families experiencing homelessness to balloon, more than five years after Bloomberg promised to reduce the homeless population by two-thirds.28

Note: Citations and sources for data are included in the PDF version of this document available by clicking Downloads underneath the Table of Contents.

Timeline of Family Homelessness in NYC from Koch through Bloomberg

Click on this timeline below for a fullscreen view, or download a PDF of the timeline as a spread or individual pages.

Note: This PDF can also be found by clicking Downloads underneath the Table of Contents.

How Mayor Bill de Blasio Contended with Family Homelessness

Mayor Bill de Blasio won the 2013 mayoral election on a progressive platform aimed at reducing economic and racial inequality and fighting “the tale of two New Yorks,” as he phrased it, that had been fostered by previous administrations and the economic conditions post-2008 recession. Issues such as the disproportionate targeting of New Yorkers of color through stop and frisk, rising income inequality, an increasing number of people experiencing homelessness, and the perception of elitism in City Hall contributed to the success of the de Blasio campaign.

A month before the mayor’s inauguration, in December 2013, the New York Times released a five-part series on the state of family homelessness in New York City. Specifically, the story followed Dasani, an 11-year-old girl living with her parents and seven younger siblings in a homeless shelter in the gentrifying neighborhood of Fort Greene, Brooklyn.29 The series not only exposed squalid conditions at one of the City’s homeless shelters, it also shadowed Dasani and her family as they struggled to overcome their circumstances. The exposé captivated public officials and city residents alike, bringing the issue of family homelessness to the forefront of public consciousness.

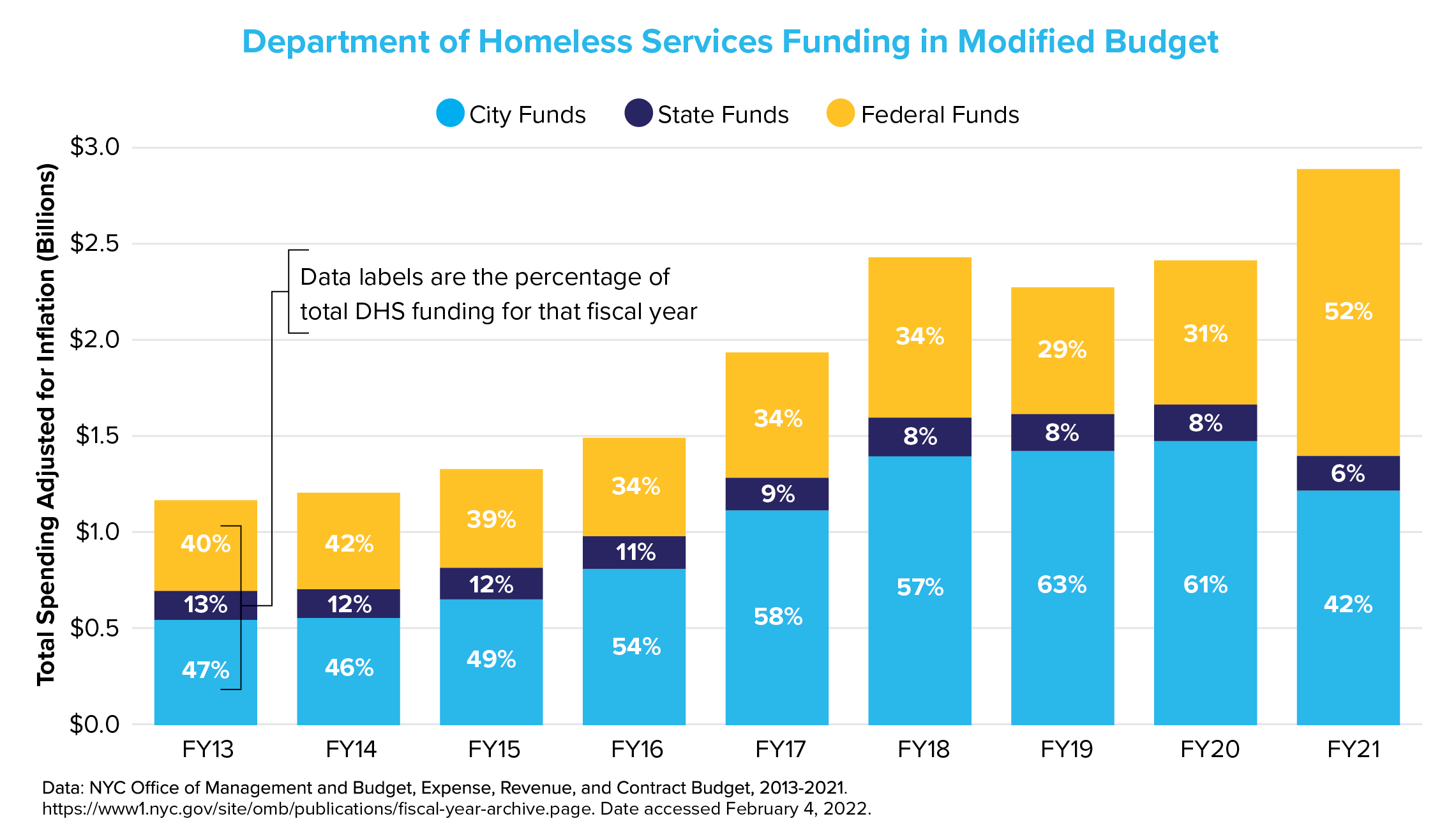

Despite this spotlight on family homelessness and the opportunity it presented for change, family homelessness remained a challenge throughout the de Blasio administration. While family homelessness decreased beginning in late 2019, there were still over 8,000 families in the system as of the time of publication, with the vast majority identifying as Black and Hispanic. Inequality and poverty have persisted, as well, compounded by the devastating impacts of COVID-19. De Blasio, like the four mayors before him, struggled to manage the dearth of affordable housing, voucher access and functionality, and economic stratification that drive the city’s inequities—and the family homelessness census. By the end of his tenure, the administration doubled the Department of Homeless Services’ budget, from what would have been $1.1 billion in 2021 dollars in FY 2015,30 to $2.2 billion in FY 2022.31 In the following sections, we will examine these policy and funding decisions and the environment in which the decisions were made, in order to assess the de Blasio administration’s ability to contend with these challenges.

The Outside Comes Inside: Advocates Have the Opportunity to Run the City’s Social Services

De Blasio’s first step in tackling the crisis of inequality and poverty was assembling a team that could help him operationalize the ideas on which he had been elected. As the Chair of the New York City Council’s General Welfare Committee and, more recently, as the New York City Public Advocate, de Blasio had himself called for significant change in how homelessness was dealt with during the Bloomberg administration.32 Here was his opportunity to build a team that could enact the change he sought.

Shortly after taking office, Mayor de Blasio appointed Gilbert Taylor, a former top official with the Administration for Children’s Services (ACS), to become the Commissioner of DHS, and Steve Banks, a former Legal Aid Society attorney, to become the Commissioner of HRA. Banks’ path to running HRA was highly unusual. As an attorney for the Legal Aid Society, he had sued the City to grant the Right to Shelter for all New Yorkers, arguably the most consequential piece of homelessness policy in the City’s history. For decades, he was “one of the fiercest advocates for the rights of people experiencing homelessness.”33 The Banks appointment made by de Blasio stands in stark contrast to the appointments made by previous administrations, which did not often hire advocates to run City agencies. For some, hopes were high that Banks’ unique perspective and experience as an advocate for individuals experiencing homelessness would lead to meaningful progress in finally tackling the City’s homelessness crisis. Others were shocked that de Blasio would hire someone who was such a longtime adversary to the City’s social service agencies, and some worried that Banks’ determination to expand social services for low-income New Yorkers would hurt the City as a whole.34 Once appointed as the head of HRA, Banks quickly pivoted away from the policies enacted by the Bloomberg administration.35 He was excited by the tools he could now wield within government to improve the lives of low-income New Yorkers.36

After Taylor stepped down in December 2015 amid a growing shelter census, the City began a 90-day review of its homelessness programs. Among other reforms, this review determined that consolidating DHS and HRA into a new Department of Social Services (DSS) would be the most efficient use of City resources and would help streamline service delivery. There was also recognition that addressing the challenge of homelessness does not exist independently from other social services; there remain continual calls for the further de-siloing of City agencies to promote coordination to curb homelessness to this day.37 De Blasio tasked Banks with leading the newly merged DSS.

Additionally, while he was not a part of the administration, it is important to note that former Governor Andrew Cuomo played an essential role in shaping the City’s social services while de Blasio was in office. Because of his experience working on the issue, some expected more progress when Cuomo became governor in 2011. Earlier in his career, in 1991, Cuomo had been appointed to lead the Cuomo Commission by Mayor Dinkins to reinvigorate the City’s homelessness policies. Cuomo was selected, in part, because he was the founder of HELP USA, an organization that operates homeless shelters, builds affordable housing, and offers support to those experiencing housing instability. Cuomo also held leadership roles at the federal agency for Housing and Urban Development (HUD). The Cuomo Commission recommended many policies that are still relevant today, such as the need for service-rich, nonprofit shelters. Between Cuomo and Banks, many of the key players in the City’s handling of social services were now those who, at times, had helped shape those social services from the outside.

A Crumbling and Insufficient Shelter System Creates Operational Obstacles

After Mayor Bloomberg’s failed attempts to control the shelter census, the shelter infrastructure de Blasio inherited proved insufficient to accommodate the soaring number of families in need. When de Blasio took office in 2013, there were over 12,000 families in the system. That number had climbed to over 13,000 by the spring of 2014.

Compounding the challenge, the City also struggled to coordinate funding for homeless services with New York State. As the family census increased, so too did the amount it cost to shelter them. At the same time, the State, under former Governor Cuomo’s leadership, paid proportionally less for homeless services and required the City to foot more of the bill.38 Despite Cuomo having worked on the issue of homelessness in New York City since the 1980s, the State was taking less and less responsibility for paying the costs of the services he had once advocated for.

Cluster sites and commercial hotels were always intended to be temporary solutions, but as homelessness surged in New York City, more and more families were placed in these units, and conditions deteriorated. When Mayor de Blasio took office, over 40 percent of all homeless families with children were living in cluster sites and hotels.39 At his request, the City Department of Investigation (DOI) launched an exploration into shelters operated and managed by DHS. The report, published in March 2015, found concerning health and safety violations in cluster sites, hotels, and Tier II facilities, particularly in those facilities operating without a City contract. Cluster sites, specifically, were found to be “the worst maintained, the most poorly monitored, and provide the least adequate social services to families.”40 Meanwhile, DHS was paying landlords two to three times the market rate to place families in these insufficient apartments.4

In response to the DOI report, the administration launched the Shelter Repair Squad—a rapid response team deployed to shelters needing repairs.42 In January 2016, the administration launched the Shelter Repair Squad 2.0. This group was tasked with conducting shelter inspections more frequently, creating a complaint hotline for shelter residents, and deploying shelter condition monitors with the goal of increased transparency in the shelter system.43

Despite a continually rising number of people experiencing homelessness, the de Blasio administration halted opening new shelters in 2015, after intense community opposition to the 16 he had built in his first year.44 As a result, the City was forced to enter into contracts with additional commercial hotels to make sure there were enough rooms for all the families coming into the City’s family intake center, the Prevention Assistance and Temporary Housing (PATH) Center. By the end of 2016, however, an analysis by New York City Comptroller Scott Stringer into the cost of DHS’s use of commercial hotels made headlines when it revealed that in the previous year, the City spent an average of $400,000 per night on hotel rooms for the homeless. In fact, the City was placing some DHS clients in hotel rooms near Times Square for as much as $629 per night. The report also found that the number of DHS clients placed in hotel rooms had grown by over 500 percent in less than a year.45 Given the high cost and lack of social services at hotels, Stringer called for a comprehensive roadmap of how the City planned to end the use of hotels to shelter the homeless.46

Not only were commercial hotels proven to be a costly solution to sheltering homeless families, they also posed safety threats. In February 2016, the City’s use of commercial hotels came under fire when a mother and two of her children were fatally stabbed in their motel room on Staten Island.47 In addition, a January 2018 DOI report found that arrests for criminal activity such as prostitution, assault, and drug use had occurred at over half of the hotels DHS was using to place homeless families with children, and that DHS was not assessing hotels for illegal activity before placing families in these facilities. DHS agreed to DOI recommendations that it consider public safety as part of its approval criteria for placing families at commercial hotels, and that whenever possible, the agency would rent out entire hotels for families with children instead of select rooms.

Meanwhile, a tragic event at a Bronx cluster site in December 2016 intensified calls for the City to end its use of the cluster site program. Two toddlers in a cluster site apartment were asleep in their bedroom when a radiator valve exploded, releasing steam into the room, severely burning them, and causing their deaths. The mayor promised a multiagency investigation and committed to preventing tragedies like this one in the future,48 as well as assigning the NYPD to help oversee security at the City’s homeless shelters (a policy that ended in the summer of 2020).49 By the end of 2016, Mayor de Blasio and Commissioner Banks had advised the closure of cluster sites and commercial hotels for sheltering the homeless. Yet, without a plan in place, little progress could be made on that goal.

Ultimately, the lack of existing capacity in the shelter system and the growing costs for the City presented operational obstacles that prevented Banks and the rest of the de Blasio administration from immediately effecting the changes they wanted on the shelter population and structure. They were forced to continue to place families in hotels and cluster sites, compromising the wellbeing of the families and burdening the City financially.

Turning the Tide: A Shelter Overhaul Meets Community Opposition

In February 2017, the de Blasio administration released Turning the Tide on Homelessness in New York City—an ambitious plan to restructure and expand the city’s shelter system. At the time, the administration was dependent upon 360 cluster sites and commercial hotels to accommodate overflow from the City’s traditional shelter system. The plan aimed to end the use of cluster sites by 2021 and hotels by 2023 and replace them with 90 new service-rich shelters and 30 renovated and expanded shelters, to be distributed equitably throughout the city over the subsequent five years.50 Turning the Tide also included plans to reduce the number of people in the homeless services system by four percent over five years, or 2,500, a far cry from the more ambitious goal originally set by the administration as de Blasio took office.51

While commendable for its goal of giving all those who experience homelessness access to high-quality shelter in their neighborhood, Turning the Tide was met with much community opposition. As the City began proposing new sites for shelters, backlash was fiercely expressed at public meetings, in the press, and even in lawsuits.52 Even in 2021, with the administration four-and-a-half years into the Turning the Tide plan, this “not-in-my-backyard” (NIMBY) sentiment persisted as the City sited shelters across the five boroughs.

While NIMBYism delayed some plans for new shelters, significant progress has been made toward the administration’s goal, with 49 new shelters opened as of November 2021 and locations determined for 99 others.53

A huge accomplishment of the de Blasio administration was officially ending the cluster site program, with the last phased out on October 30, 2021.54 In June 2021, the de Blasio administration spent $122 million on a 14-building portfolio of cluster site apartments with the plan to turn the 777 units into permanently affordable housing—554 units designated for the formerly homeless.55 While this purchase was lauded by advocates, the buildings purchased had more than 1,100 open violations with the Department of Housing Preservation and Development (HPD), which made many of them uninhabitable. The nonprofit organizations that, as of June 2021, manage the buildings have years of work ahead of them to ensure that these units enable formerly homeless New Yorkers to live in safe and dignified conditions.56 Again, while well-intentioned, this strategy’s success has been hampered by operational challenges.

Keeping New Yorkers Housed: Homelessness Prevention, Vouchers, and Housing

Homelessness Prevention

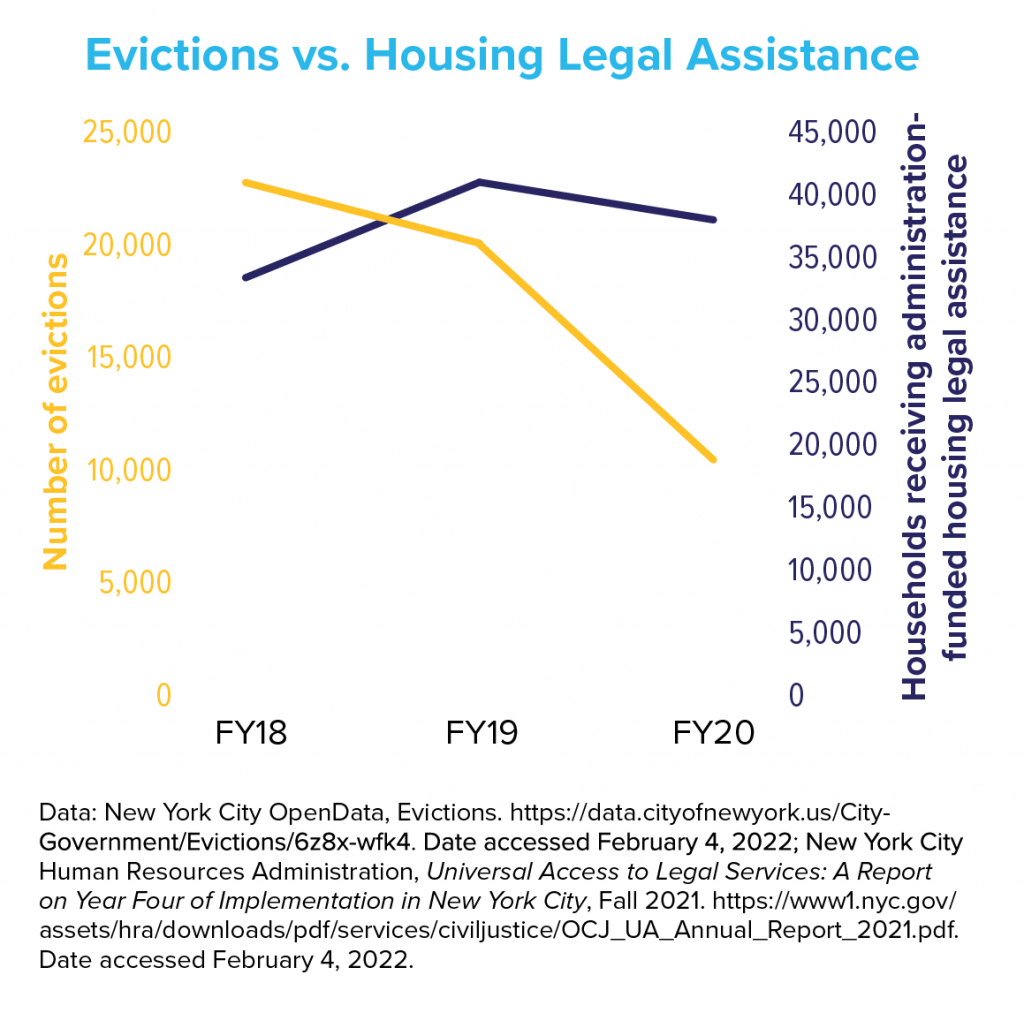

One of the main goals of de Blasio’s Turning the Tide was to keep New Yorkers in their homes and out of the shelter system.57 For Banks and de Blasio, homelessness prevention was a key element of their strategy. Their ability to drive family homelessness down hinged on the bet that prioritizing diversion would work. Between 2013 and 2021, City spending on tenant legal services increased by more than 2000 percent.58 Spending on Homebase, a City program that aims to prevent homelessness that began in 2004, increased by over 600 percent between 2005 and 2018.59 Banks and de Blasio also allocated resources to “one-shot deals” and other rental assistance programs, which help tenants pay back rent that they owe in the hopes of preventing their evictions.

Eviction is the second-leading cause of family homelessness in New York City, behind domestic violence. In FY 2019, 21 percent of families in DHS shelter entered due to an eviction.60 In August 2017, New York City became the first municipality in the country to implement a legal “Right to Counsel” for residents facing eviction in housing court. Tenants with incomes below 200 percent of the federal poverty level have access to the program, which was initially phased in by zip code. The zip codes with the highest numbers of evictions and shelter entries were first to receive the program. In 2021, the program’s extension to all zip codes was fast-tracked in light of the COVID-19 pandemic, and as of June 1, 2021, all tenants in the five boroughs have access to an attorney in housing court.61 Data indicate that the Right to Counsel is reducing the number of New York City tenants facing eviction. The number of residential evictions in the city declined by 19 percent from 2017 to 2019. From July 2020 to July 2021, 84 percent of tenants represented by attorneys were able to remain in their homes, though there were many fewer eviction filings due to the COVID-19 eviction moratorium in effect in New York City from March 2020 through January 2022.62

New Yorkers were also protected from homelessness and eviction through the proliferation of Homebase, which, under de Blasio, expanded to 26 locations throughout New York City. The de Blasio administration’s 90-day review led to several reforms of the program. Officials consolidated Homebase, a DHS program, with HRA’s homelessness prevention programs and made Homebase the first entry point for New Yorkers at risk of homelessness.63 The budget for Homebase also expanded from $11 million in FY 2005 to $81 million in 2018, and at least $53 million annually through 2021.64 In FY 2021, 97 percent of families with children who enrolled in Homebase were successfully diverted through preventative services from entering shelters.65

Rental Subsidies

Critical to any strategy to decrease family homelessness is investment into rental subsidies to help families exit shelter. When de Blasio entered office, there had been no replacement voucher for Bloomberg’s Advantage program, which ended in 2011. Many families whose voucher period ended under that program reentered shelters, and many others confronting increasing unaffordability in housing flooded into the system. To address this, the de Blasio administration established the six-part Living in Communities (LINC) program and the City Family Eviction Prevention Supplement (CITYFEPS) program in 2014. For four years, this patchwork of rental subsidies was unwieldy for the City. Administration was inefficient and also made it difficult to detect source of income discrimination by landlords—a common but illegal practice that to this day prevents families with housing vouchers from being able to leave shelter. Oftentimes, a family will have a voucher for years but will be unable to find an apartment because landlords refuse to rent to them.

In an effort to simplify rent subsidies, the City combined LINC I, II, IV, and V, CITYFEPS, and Special Exit and Prevention Supplement (SEPS) into one streamlined program—CityFHEPS, or the City Fighting Homelessness and Eviction Prevention Supplement—in July 2018.

Adding to the list of programs, in September 2017, the City created yet another rental assistance program called Special One-Time Assistance, or SOTA. SOTA pays one year of rent for families or individuals to leave DHS shelter and move anywhere in the United States. The SOTA program has been quite controversial. First, a DOI report found that SOTA recipients were being placed in uninspected units that often lacked heat or had vermin infestations, among other issues. Second, Newark, New Jersey, filed a lawsuit against the City for its use of SOTA, claiming that SOTA constitutes a public nuisance. The Legal Aid Society also engaged in litigation, suing both Newark for discrimination against low-income renters, and New York City to strengthen SOTA.

The changes sought by Legal Aid were enacted by DHS in September 2021, ensuring that apartments are safer and capping SOTA rents at 40 percent of the recipient’s income, in the hopes that they will be more likely to afford the rent after the one-year subsidy runs out. Prior to these changes, SOTA was a prime example of the challenge of using rapid rehousing strategies for families. Giving families a short-term rental subsidy, moving them to a new location without proper vetting of apartments, and providing them with little to no support has proven to be an unsustainable method of keeping families stably housed. Rapid rehousing programs are often a short-term solution to family homelessness: after the subsidy runs out, many families end up back at the shelter door. In the case of SOTA, nearly seven percent of recipients returned to shelter within the first three years of the program. This rate is much higher than that of holders of other vouchers over that same time span.66

These tensions regarding rental subsidy length and purchasing power showed up in debates around the changes made to CityFHEPS in May 2021. After years of advocacy by homelessness advocates and formerly homeless New Yorkers, the City Council passed Local Law 146, which increased the rental amount covered by the voucher to be more in line with rental costs. Whereas the previous vouchers were capped at $1,265 a month for a single adult and $1,580 for a family of three or four, this law increased their value to roughly that of Section 8 vouchers—which cover one-bedroom apartments at $1,945 per month and two-bedroom apartments at $2,217. The law also extended their lifetime; voucher holders would no longer lose their vouchers after five years. However, the final bill—which was much anticipated and celebrated—contained a few last-minute changes that compromised its effectiveness and ability to truly help families succeed. In the original version, households could renew their vouchers until they could pay 30 percent of their rent. In the version that became law, households will lose their vouchers after five years if their incomes reach more than 250 percent above the federal poverty level. For a family of three, this would be just shy of $55,000 annually. Families would once again be forced to make the choice of maintaining un- or under-employment, or risking the loss of their voucher.

However, through additional advocacy by practitioners, formerly homeless New Yorkers, and activists, these concerns were addressed by a DSS rule change in November 2021. After five years, recipients will remain eligible unless they earn 80 percent of Area Median Income (AMI) or more —currently $66,880 for an individual or $85,920 for a family of three. Furthermore, under pressure from organizers and advocates, de Blasio also fast-tracked the increase in value of CityFHEPS vouchers in August 2021. The changes went into effect in September 2021. This constitutes a significant improvement in the program, but it remains to be seen to what extent this will enable homeless families to move out more quickly and into better apartments.

Housing

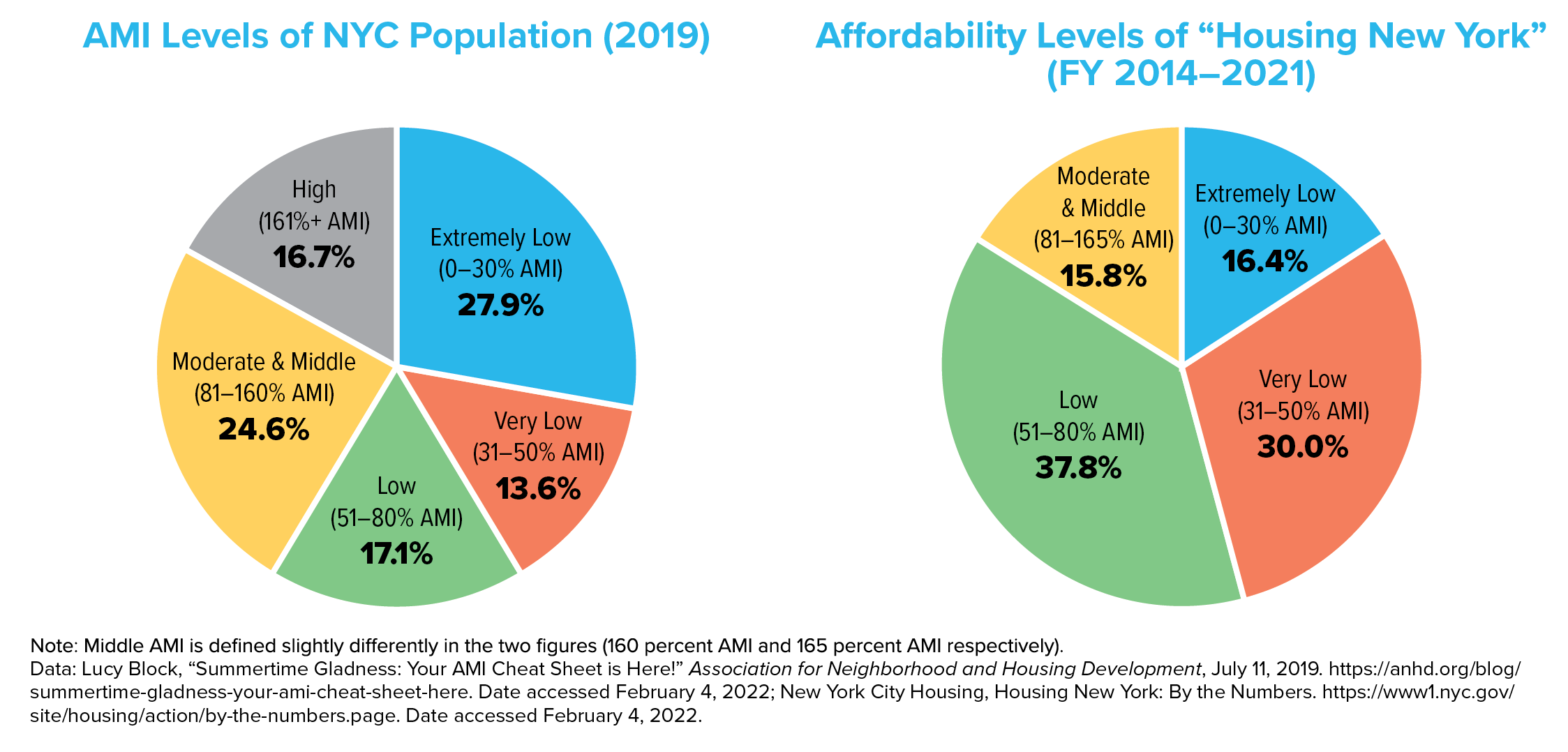

Like many of his predecessors, Mayor de Blasio set his sights on bolstering the City’s affordable housing stock when he came into office. Five months into his mayorship, his administration released Housing New York: A Five-Borough, Ten-Year Plan. The document broadly outlined how the City would create and preserve 200,000 affordable housing units by 2024. The City is on track to meet this goal ahead of schedule and therefore launched Housing New York 2.0 in November 2017, which updated the City’s commitment. In Housing New York 2.0, the City aims to create and preserve 300,000 affordable homes by 2026. Unfortunately, however, the administration again and again prioritized quantity of housing units over depth of affordability.

As of December 31, 2021, the de Blasio administration had created or preserved 202,834 affordable units.67 While impressive, there were concerns among advocates for the homeless that these units did not actually meet the needs of those who need affordable housing the most—homeless New Yorkers. Only 8 percent of the housing built thus far is part of the Homeless Start Program, and 16 percent is for New Yorkers with extremely low incomes (0-30 percent AMI, which in 2021 was $32,220 or less for a family of three).68 In Housing New York 2.0, the administration committed to setting aside 15,000 apartments for homeless households—approximately 9,000 of which would be preserved, not constructed. This means that while affordability would be maintained, the stock of housing available for families in shelter would not expand as only a few of these units would turn over each year.69 In late 2019, de Blasio finally supported a Local Law that passed in City Council requiring that affordable housing projects with 40 or more units set aside 15 percent of new units for homeless New Yorkers.70 The Coalition for the Homeless has argued that if this set-aside had existed from the beginning of the mayor’s tenure in 2014, nearly three times as much housing for the homeless would have been built than projected in his Housing New York 2.0 plan.71

In the original Housing New York plan, the goal was to reserve 20 percent of affordable units for extremely low income and very low income renters,72 revised in Housing New York 2.0 to 25 percent of units.73 However, this still did not go far enough to meet the needs of New York’s most vulnerable households. A 2019 fact sheet from the Association for Neighborhood and Housing Development showed that two in every five New Yorkers (42 percent) were extremely low income or very low income,74 making less than 50 percent of AMI, which in 2021 was $53,700 for a family of three.75 That percentage – 42 percent – is likely to have increased due to the economic devastation of the COVID-19 pandemic. And families in shelter and exiting shelter typically earn far less than 50 percent of AMI. A report from the National Low Income Housing Coalition found that average annual income for a family after exiting shelter was $13,531,76 which in 2021 dollars was just over $15,000, or 14 percent of AMI. With this stark reality in mind, it is clear that Housing New York 2.0 did not go far enough to ensure affordable housing as a solution to homelessness.

The de Blasio administration also initiated a policy of Mandatory Inclusionary Zoning, which changed the City’s zoning code so that when an area is upzoned, or the number of housing units that can be built there is increased, a number of those units must be targeted toward certain incomes. Again, the administration prioritized quantity of housing produced over the depth of affordability offered, with units targeted toward those with middle incomes as opposed to low incomes.77 Thus, this policy, too, did not create housing options accessible to homeless families.

The current lack of affordable housing leaves millions of New Yorkers rent-burdened, or paying more than 30 percent of their income toward rent. In 2018, more than half (53 percent) of New York City’s renting households were rent-burdened, including the over one-quarter (28 percent) of New Yorkers who were severely rent-burdened, spending over half of their household income on rent. This puts significant pressure on families and can lead to them falling into homelessness when they can no longer afford their rent.

Any discussion of the housing market is incomplete without mentioning the role of gentrification. Gentrification across New York City has placed low-income residents in peril, as those living on the fringe of the rental market can no longer afford rent in the areas where they have always lived. Thousands of New Yorkers, particularly those of color, have been priced out of their own neighborhoods, making room for the influx of better resourced and often white newcomers able to pay higher rents.78 Displaced low-income families must piece together temporary living situations, doubling and tripling up with friends and relatives, before eventually turning to the city’s emergency shelter system.

Anti-Poverty Policies and Social Support to Combat Family Homelessness

Any assessment of Mayor de Blasio’s attempts to curb family homelessness must examine his policy decisions around providing social services and addressing poverty more broadly. De Blasio campaigned on ending “the tale of two cities.” While the family shelter census decreased through his tenure, and a decrease did begin before the eviction moratorium in 2020, to what extent did the lives of extremely low-income and homeless New Yorkers improve? It was important for Banks and de Blasio to tackle the root causes of family homelessness—such as systemic racism and disparities in educational and employment access—and the policies detailed below aimed to fulfill this goal.

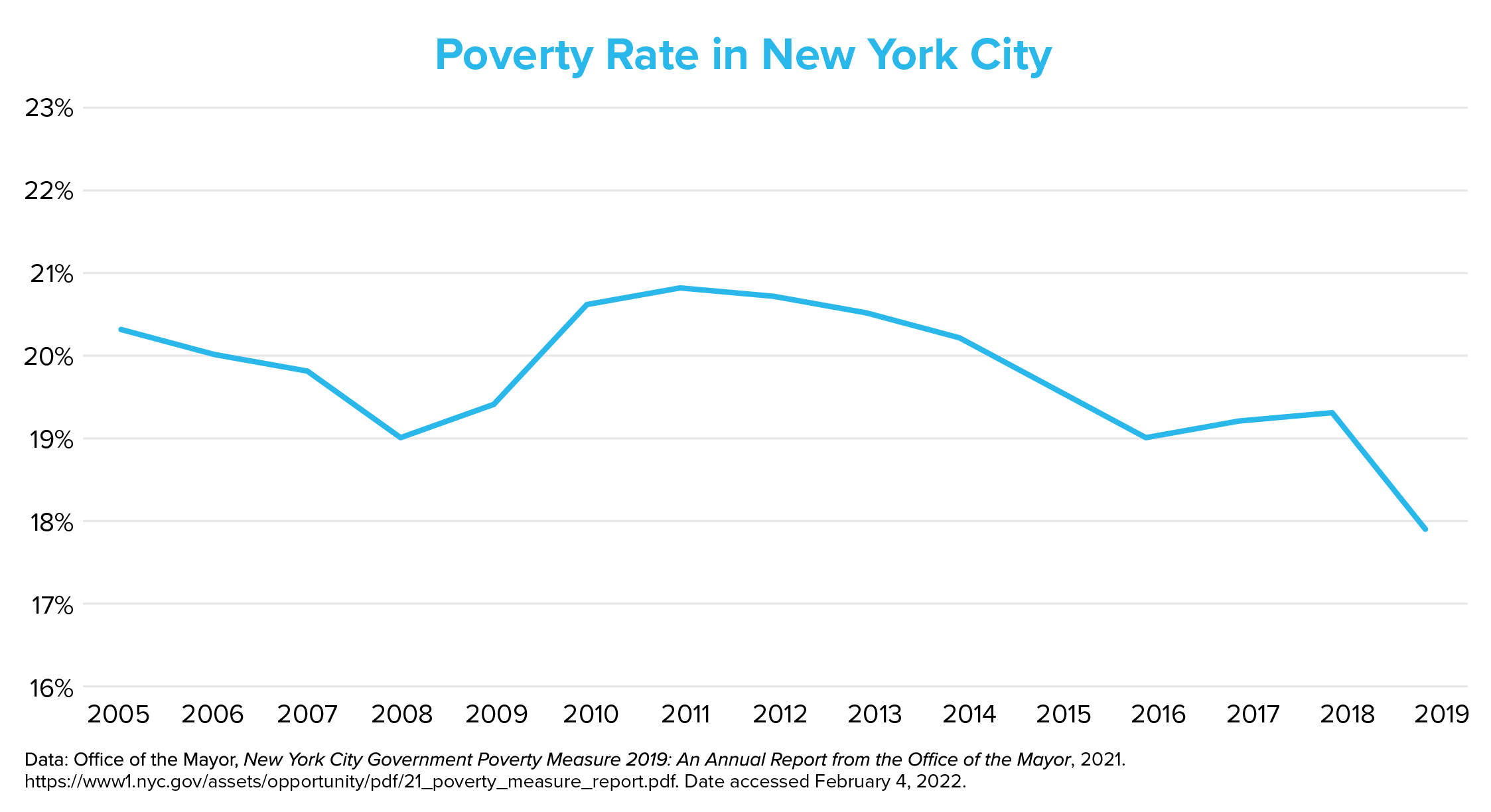

In a report the de Blasio administration published a month before he left office, he notes that by 2019, the wage share for the bottom 50 percent of earners rose by 15 percent while it fell for many workers in the top 20 percent of earners. Furthermore, New York City’s poverty rate decreased to approximately 13 percent, the lowest rate since 2005, when the City began tracking it.79 There are several key policies that may have contributed to these trends—and may continue to improve the lives of low-income and homeless New Yorkers in the years to come.

Two of de Blasio’s most significant achievements are universal Pre-K and 3K programs, which provides early education to all children in New York City. This policy helps families save money on daycare and childcare and enables them to access employment. The long-term economic and social benefits of quality early education for the city’s children have yet to be seen, but they will likely be significant and may help stop the cycle of homelessness in the city.

The increase in the minimum wage under de Blasio has also contributed to a decrease in poverty in New York City. The mayor had advocated for an increase from New York State since 2014, and through concerted pressure on Governor Cuomo, helped the labor unions’ movement to achieve a $15 minimum wage (“Fight for $15”) in 2016.80 By the end of 2019, all New York City workers earned at least $15 per hour. However, even earning $15 an hour doesn’t enable a family to afford the median price of a New York City two-bedroom apartment, which in 2021 required an average wage of $39.48 per hour.81

De Blasio also initiated paid sick time off by signing the Earned Sick Time Act in 2014. Through this policy, 500,000 New Yorkers were able to take paid time off of work when sick, continuing to earn money and holding onto their jobs. This policy has since been expanded to more workers and now includes safe leave as well, for survivors of domestic violence.82 Losing one’s job can push a family into homelessness; by increasing job stability and improving the economic wellbeing of New Yorkers, the administration hoped to quell the tide of homeless families into the shelter system.

To address the epidemic of domestic violence, a main driver of family homelessness in the city, de Blasio created the NYC Domestic Violence Task Force in 2016.83 Taking action on their recommendations in 2017, he invested $7 million in services for survivors, including legal services, support for children who witness domestic violence, and technology to help survivors better prove their cases.84 Still, domestic violence continues to be a serious problem, increasing in magnitude during the COVID-19 pandemic. While we may not see all of the effects of these social services right away, they have the potential to create lasting impacts on poverty in New York City and play a critical role in reducing family homelessness in the long term.

A Turbulent End to the Mayor’s Tenure

The last two years of Mayor de Blasio’s second term were marked by the disruptions of a failed presidential campaign and the catastrophic arrival of the COVID-19 pandemic.

In May 2019, Mayor de Blasio announced his candidacy for president, joining a crowded field of 22 other Democrats seeking the party’s nomination.85 From the beginning, it was an underdog campaign. He attempted to occupy the progressive lane of the party already being represented by Senators Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren. Although he qualified for the first two debates, his campaign never gained traction, and he withdrew from the race in September 2019.

Then, at the end of March 2020, the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) upended New York City. At the height of the pandemic, in early April 2020, over 6,000 New Yorkers were testing positive for COVID-19 each day.86 New York City officials were struggling to keep the virus at bay as the city became the epicenter of the crisis in the United States. COVID-19 infection and death hit communities of color the hardest, with the fatality rate of Black and Hispanic New Yorkers more than double that of white New Yorkers.87 The inequities would be seen in economic and social impacts as well—job loss, access to education, and more. As family homelessness is already an issue that disproportionately impacts New Yorkers of color—94 percent of the heads of households in DHS family shelters are Black or Hispanic88—COVID-19 and its impacts are especially disturbing and concerning.

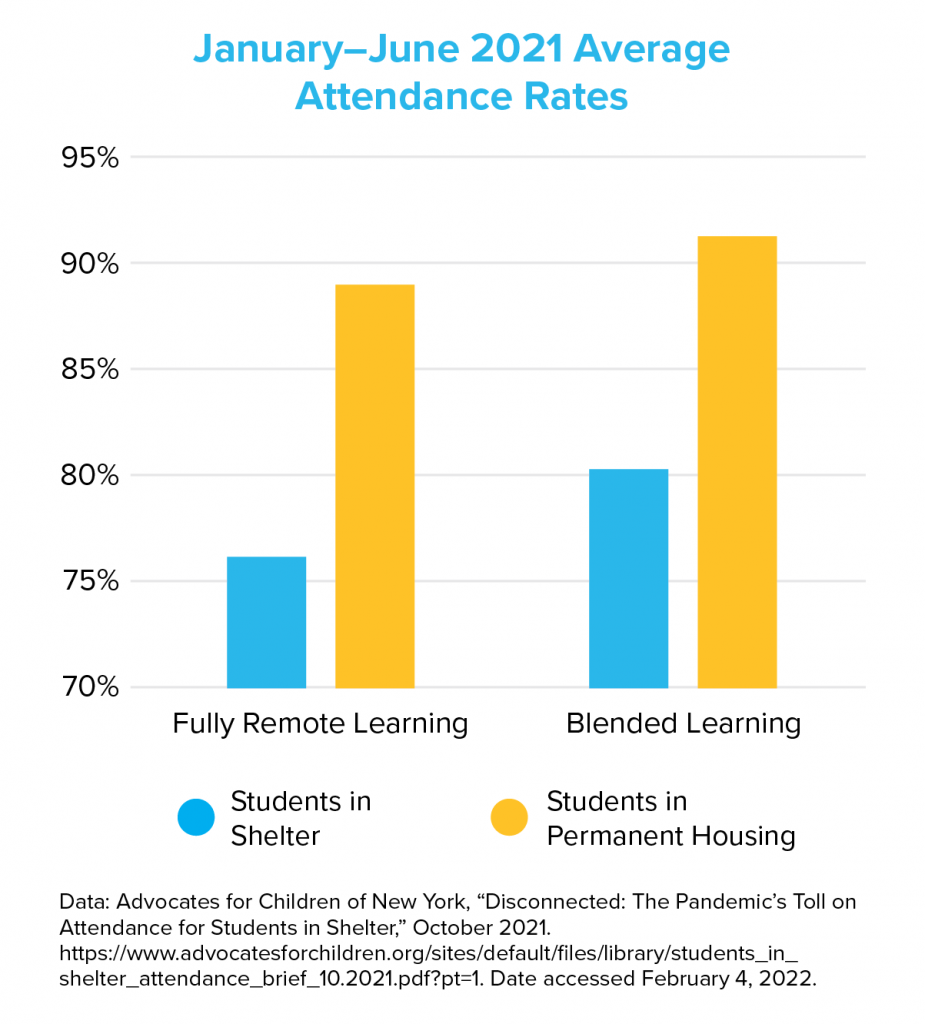

After an initial hesitation to close New York City public schools (due to concerns around childcare for essential worker parents and access to school-based meals and other services that children and families depend on), de Blasio shut down in-person instruction on March 15, 2020, and 1.1 million children, including over 20,400 homeless children in shelter, began learning remotely by March 23.89

This transition to remote instruction was far from seamless. Many of the City’s homeless and low-income students lacked internet service or access to a computer or tablet at home, contributing to high absenteeism rates during lockdown. The City scrambled to distribute 300,000 devices with built-in internet to students, prioritizing students in shelter.90 Still, more than a month after schools shut down, thousands of children were still waiting for the devices they had requested from the Department of Education. Stories of homeless children attempting to use a parent’s smartphone to log onto remote classes, multiple siblings sharing one iPad, and students in shelter or doubled-up conditions lacking privacy to do schoolwork were all too common.91

In the fall of 2020, the de Blasio administration and the DOE allowed students to come back to school remotely or through a blended model. School buildings were shut down in mid-November—less than two months after opening, however. Elementary schools reopened on December 7, 2020.92 District 75 special education schools for grades K–12 returned on December 10,93 but all other middle and high schoolers citywide were kept remote until February 25, 202194 and March 22, 2021,95 respectively. A policy brief by Advocates for Children of New York examined the impact of remote and blended learning on homeless students during the school year. Their analysis found that overall monthly attendance rates for students living in shelter were dramatically lower (10.6 to 14.1 percentage points) than those of students living in permanent housing.

Absentee rates were particularly striking for high school students: 10th graders missed one out of three days of school and 9th, 11th, and 12th graders were out of school over 25 percent of the time.96

Pivoting to online instruction for public school students and navigating the transition back to in-person and blended learning was just one of many challenges the city faced as the epicenter of the pandemic in the United States.

With mounting concerns for residents’ health and economic wellbeing, Governor Cuomo paused all evictions in the state through executive order in late March 2020. In December 2020, the eviction moratorium was signed into law by the New York State Legislature, originally in place through May 1, 2021.97 On May 4, the state moratorium was extended through August 31. In September 2021, it was extended once again, until January 15, 2022.98 The U.S. Centers for Disease Control (CDC) also instituted a federal eviction moratorium, though its extension was effectively struck down by the Supreme Court in August 2021.99 Due in part to the halt on evictions going through housing court, DHS’ family shelter census continued to go down through 2020 and 2021, as families were able to stay in their homes.

A person’s ability—and, in the early months, requirement—to isolate in their home had many positive benefits, but also likely contributed to a deeply troubling development: a spike in domestic violence. In April 2020, New York State’s domestic violence hotline received 30 percent more calls than in April 2019; between February and March 2020, calls increased by nearly 20 percent.100 Many domestic violence survivors may have stayed with their abusers rather than enter a shelter due to fear of contracting the virus. In May 2020, de Blasio responded to this crisis by creating an Emergency Relief Program for survivors of domestic and gender-based violence that provides them with immediate financial assistance for housing, safety, and economic needs.101

The economic devastation created by COVID-19 will take years to recover from. The closure of all non-essential businesses wreaked havoc on the city’s economy in 2020. Struggling businesses, particularly those in the retail and service industries, were forced to lay off workers. In June 2020, the city’s unemployment rate hit 20 percent—a rate not seen since the Great Depression.102 Many businesses closed permanently. As of September 2021, the unemployment rate was 9.8 percent—nearly three times the city’s rate pre-COVID-19.103 According to National Equity Atlas, which analyzed the U.S. Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey, over 650,000 households in the New York City metro area were behind on rent as of October 2021, and 43 percent of these households were families with children.104

In the face of this hardship, housing and homelessness advocates organized around a cancellation of rent throughout 2020 and 2021. Instead, with support from the federal government, New York State funded an Emergency Rental Assistance Program (ERAP), which launched in June 2021. Tenants who fell behind in rent due to the pandemic, qualified for unemployment benefits or lost income due to the pandemic, and had an income below 80 percent of AMI were eligible for up to 12 months of back rent paid, among other benefits.105 Controversially, on November 14, 2021, New York State stopped accepting applications for aid, maintaining that the $2.4 billion in ERAP funds had been depleted. Between June 1 and early November, 280,000 households submitted applications, and 81,209 payments had been made.106 Demand for these funds remains high, and Governor Kathy Hochul has requested additional funds from the federal government to meet this need. Without additional ERAP support, and with the moratorium lifted in January 2022, an uptick in the family homelessness census is expected.

The COVID-19 pandemic and the resulting economic challenges, supportive governmental programs, and changing city dynamics have had and will continue to have an influence on family homelessness. The Mayor’s Management Report from FY 2021 shows that an average of 9,823 families with children stayed in shelter per day, a 16 percent decrease from FY 2020. The number of families entering shelter decreased even more notably—from over 10,000 to just over 6,000. However, this decrease in the number of families has been coupled with an increase in length of stay. Families with children are staying in shelter for an average of two and a half months longer than in FY 2020.107 While the administration claimed that this was due to the difficulties in safely viewing apartments during the pandemic, some advocates believe that it highlights the difficulties in finding affordable housing.108

Conclusion

Bill de Blasio was elected largely because of the promise to fight inequality in New York City. He hired longtime advocate Steve Banks to manage HRA, and eventually DHS. Out of the gate, Banks and de Blasio struggled to balance their personal beliefs about the shelter system—that we should ease our reliance on the system and do everything in our power to keep families housed—with the reality that they simply had to have enough beds in the system to comply with the Right to Shelter ruling. Their plan to focus on long-term solutions to homelessness—housing production and income equality, being two examples—created a tension with the real and immediate needs of families in and entering shelter. This resulted in enormous expense and the use of unsafe commercial hotels that were a Band-Aid solution from 2015 to 2021.

As the number of families with children in shelter stabilized in 2017, de Blasio and his team released Turning the Tide on Homelessness in New York City. In this plan, they attempted to increase the city’s affordable housing stock, end the reliance on cluster sites and hotels to house families, and add more rental subsidy programs. These plans had their own set of obstacles, from NIMBYism to affordable housing construction that was not actually affordable for the people it was supposed to serve.

The administration also passed the Right to Counsel and increased the value of the CityFHEPS voucher. These policies, in tandem with the eviction moratorium, helped decrease the number of families with children in shelter. Lastly, de Blasio implemented universal Pre-K and 3K—the policy he will most likely be known for. This, along with other social service improvements, will help families in the long term, as it gives them the supports they need to address the economic and social issues that led them to homelessness.

With many big ideas and an average of nearly $2 billion spent each year on shelter provision alone,109 de Blasio will be the only mayor to exit office with fewer families with children in shelter than when he began his term as mayor. However, his path to this accomplishment was convoluted; it included a dramatic increase in the family shelter population during his first term, and then a dramatic decrease with the COVID-19 pandemic and eviction moratorium. Time will tell if this decrease is sustainable. It will be up to his successor to monitor the continuing impact of the pandemic and these policies and respond with urgency, in order to significantly reduce family homelessness in New York City.

Note: Citations and sources for data are included in the PDF version of this document available by clicking Downloads underneath the Table of Contents.

Mayor Adams and the Future of Family Homelessness

After winning a tight primary race—the City’s first ranked-choice mayoral contest—Eric Adams was elected mayor of New York City in November 2021. When he took office in January 2022, Adams began to direct New York City’s nearly $100 billion dollar budget and enormous administrative bureaucracy. A centrist,110 Adams campaigned on shrinking the administration, breaking down silos in City agencies, and increasing efficiencies in governmental functioning. He enters his tenure as the city navigates recovery from a pandemic that disrupted the social and economic fabric: with rising crime, high unemployment, and uncertainty around a full reopening, Adams has much to contend with.

And what will Mayor Adams do to solve family homelessness? Will the reduction in families in shelter under de Blasio be sustainable, or will it rise once again? Like many mayors before him, Adams has stated his intention to increase affordable housing as a means of driving down homelessness. As demonstrated through mayoralties over the last several decades, we know that a focus on housing production alone will not solve homelessness. Furthermore, Adams wants to make housing affordable but hasn’t detailed for whom this housing would be affordable—middle income earners or low-income earners.111 Below, we discuss the policy ideas Adams touted along the campaign path; it remains to be seen which will be implemented to address homelessness and how effective they will be.

Housing and Voucher Usage

Many of Adams’ solutions to homelessness center around access to affordable housing and vouchers that can help families and individuals find and maintain decent housing. On the campaign trail, he often criticized the CityFHEPS vouchers’ value for being too low to allow families to find apartments in the city’s increasingly expensive rental market. As a candidate, he promised to raise the value of these vouchers to meet current rents—a moot point as City Council and Mayor de Blasio increased their value in 2021.

The new mayor has also voiced support for converting private office buildings and City-owned buildings into affordable housing and commercial hotels into supportive housing units. He also touted a plan to turn shuttered hotels in the outer boroughs into 25,000 units of supportive, affordable housing.112 However, most of the city’s hotel rooms are in Manhattan, and there are many hotels in that borough that could be converted into permanent housing without expensive upgrades or zoning changes. A focus on the outer boroughs may hinder making strides where progress would be faster and more cost-effective.113 Despite the current dearth of supportive housing units, the new mayor also included in his policy platform a prioritization of homeless New Yorkers and young adults aging out of foster care for these units.

Additionally, his plans include a potentially significant idea for increasing access to the city’s affordable housing units: he would ensure that HPD’s vacant affordable housing units are filled, even if income thresholds need to be reduced and offset by subsidies.114 With thousands of New Yorkers applying for these units, and many with rents still out of reach for families in need, this policy could open up housing opportunity to families in or on the brink of homelessness.

Even more affordable housing units could be created if Adams follows through on his goals to legalize basement apartments. De Blasio, too, supported this, but in practice, it is very expensive to make these units safe, requiring significant funding and political will. In September 2021, Hurricane Ida caused flooding that led to the deaths of 13 New Yorkers, 11 of whom had been trapped in basement apartments. There is an urgent need to bring these units up to New York City code and legalize them, but estimates to do so are in the billions of dollars.115 Finally, Adams wants to bring back single room occupancy units (SROs). A focus on SROs, while important to create housing for the rising numbers of homeless single adults, will not address the needs of families in shelter, whose members compose 57 percent of the overall shelter census.116

All in all, the new mayor has clearly made it a priority to bulk up the city’s affordable housing stock. Whether he can deliver on this promise—and whether the housing and vouchers he supports will finally stem the flow of families into the shelter system—is yet to be seen.

Social Services and Economic Support

New York City’s new mayor also recognizes that the city’s economic inequities—which only deepened during the pandemic—will require targeted investments and alterations in the social safety net. Informed by his core campaign message that the City’s bureaucracy must be reorganized and streamlined, he plans to make it easier to access social services and apply for jobs through the creation of centralized programs and apps. Adams also supports increasing the minimum wage to $20 per hour to help people afford housing,117 though with the average wage needed to afford a two-bedroom unit in New York City at $39.48 per hour, this increase wouldn’t necessarily create the access he envisions.118

As a candidate, Adams also proposed a “prenatal to career” platform that would (1) support expectant mothers with prenatal care,119 (2) expand childcare access for all parents,120 (3) integrate life skills into the public school curriculum, and (4) increase job training within high schools.121 This kind of initiative can help reduce generational poverty by supporting parents and attending to the educational and social development of New York City’s young people. Children under five years of age account for nearly half of children in shelter; prenatal care and the expansion of free or subsidized childcare could alleviate many stressors in their parents’ lives. Job training and life skills education may also prevent young people from entering the homelessness system in the future, helping to alleviate the economic conditions that drive people into family homelessness.

Finally, Adams has proposed an NYC AID (Advanced Income Deployment) Plan that would both increase a family’s Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) benefits and help them receive payments on a monthly basis, instead of in a lump sum at the end of the year.122 This type of initiative could help stem the flow of families into the homelessness system and speaks to a fundamental truth about homelessness—that it must be addressed through boosting income and creating the socio-educational supports that will make income increases permanent.

Less attention has been paid in the new mayor’s plans to the large number of domestic violence survivors who reside in the City’s homeless shelters. Domestic violence is a significant driver of family homelessness; in 2018, domestic violence was the cause of homelessness for 41 percent of families entering shelter.123 Adams suggests a “Family Violence Perpetrator Program” that would address abusers’ trauma with the goal of mitigating repeat domestic violence.124 He has cited his advocacy in expanding the state-run Family Eviction Prevention Supplement (FEPS) program into the Family Homelessness and Eviction Prevention Supplement (FHEPS), which now targets domestic violence survivors. He believes FHEPS, like CityFHEPS, should be increased to fair market rent values, which in late 2021 Governor Hochul enacted.125 These are the only solutions offered in campaign policy proposals to address one of the major causes of family homelessness—an oversight that will make significantly reducing homelessness more difficult.

Conclusion

It is heartening that Eric Adams wants to eliminate silos in New York City services. As homeless advocates and people who have experienced homelessness know, the City can address homelessness only through a coordinated effort among many city agencies—Department of Homeless Services, Human Resources Administration, Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, Department of Education, Department of Youth and Community Development, Housing Preservation and Development, Department of Buildings, and others. His plans that speak to New York’s educational and economic inequities and his ideas to bolster the social safety net may indeed help halt the flow of homeless families into the system and/or make their exit from shelter sustainable at last. His focus on increasing affordable housing stock is critical, but, as we have seen through past mayoralties, difficult to deliver on.

Past mayors have all struggled to address the interconnected causes of family homelessness through housing, voucher, and social service-based interventions. Koch failed to recognize family homelessness as more than a short-term crisis, which limited his ability to implement substantial policy change. Dinkins struggled to efficiently move enough families into permanent housing as the flow of families into the shelter system continued to increase. Giuliani’s shortsighted efforts to reduce the City’s role in providing social services certainly cut spending, but also hurt families. Bloomberg’s attempts to rapidly rehouse homeless families with short-term vouchers may have helped families in the short term but often forced them to reenter the shelter system when those vouchers expired. Finally, the de Blasio administration’s attempts to slow the number of families entering shelter through structural changes—such as affordable housing development—may take years to bear out, and the pandemic further confounds our ability to assess his legacy.

It is important to note, too, that ending family homelessness will require coordination with New York State; the City alone cannot solve the problem. Mayor Adams has taken office the same year as a contested race for the governorship; who wins and the relationship Adams builds with this leader will have enormous implications for the City’s ability to deliver on economic and housing policy that would make dents in the shelter census. In the wake of de Blasio’s famously fraught relationship with former Governor Andrew Cuomo, Adams has already made the strategic move to demonstrate unity with current Governor Kathy Hochul by inviting her to his Election Night stage. Her speech that night included a promise for a “whole new era of cooperation.”126 From increasing voucher amounts to allocating funds for the construction of supportive housing, the governor and New York State legislature have tools that must be wielded in order to drive down homelessness.127 It is also critical that the needs of homeless families not be forgotten as the mayor and governor wrestle with the needs of other, more visible populations of people experiencing homelessness, for example, single adults living on the streets or subways. Despite the decline in the homeless family census in shelter currently, it is still too high, with over 14,000 children living in shelter. Now is not the time to ignore the critical needs of families experiencing homelessness and those on the brink of homelessness.

While the family homelessness census remains low for now, length of stay for shelter residents is increasing, with families staying an average of two-and-a-half months longer in FY 2020, compared with FY 2019.128 The eviction moratorium ended on January 15, 2022, and with federal unemployment benefits decreased to pre-pandemic levels as of last summer, a tidal wave of newly homeless New Yorkers will likely occur. A focus on housing production alone will not end homelessness for all families in New York City. And for these newly homeless and those already unhoused, shelters with wraparound supports, employment programs, and afterschool programs are necessary to help them get back on their feet and confront the barriers that led them to homelessness. Among these newly homeless will be thousands of children, joining those already in the system. Their educational instability—made devastatingly clear during the pandemic—will need to be addressed to support them now and as part of a long-term response to homelessness.

Over the next year, we will see if the de Blasio years created long-term structural change, or if this current decrease in the family homelessness census is the result of COVID-19-specific solutions that will unravel in the coming months. Adams will have the opportunity and responsibility to respond to either scenario; we hope he will take an approach that balances the long-term goal of producing deeply affordable housing with immediately providing enhanced critical social and educational services for homeless and low-income New Yorkers.

Note: Citations and sources for data are included in the PDF version of this document available by clicking Downloads underneath the Table of Contents.