Introduction

A quality education is the most powerful tool students experiencing homelessness have to escape housing instability and the cycle of poverty. However, for most students, breaking this cycle requires more than a high school diploma, with higher education often necessary to attain economic security.

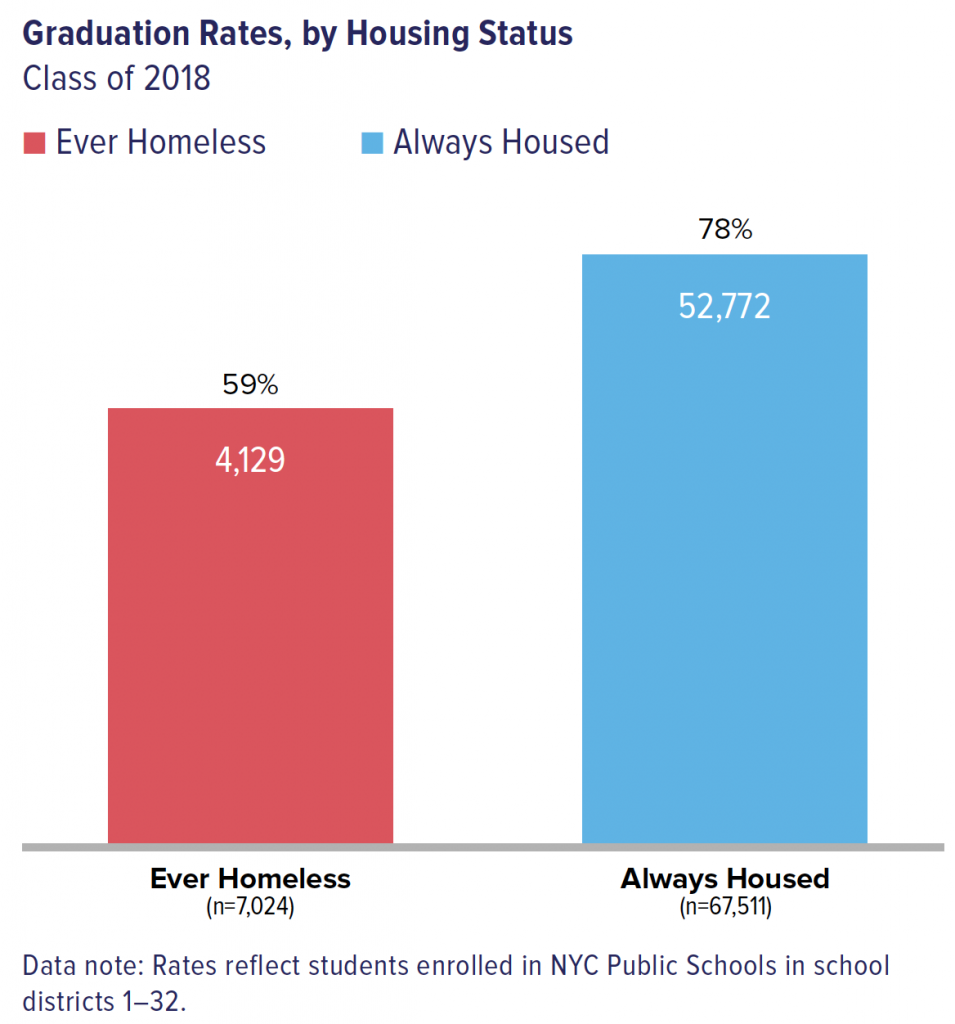

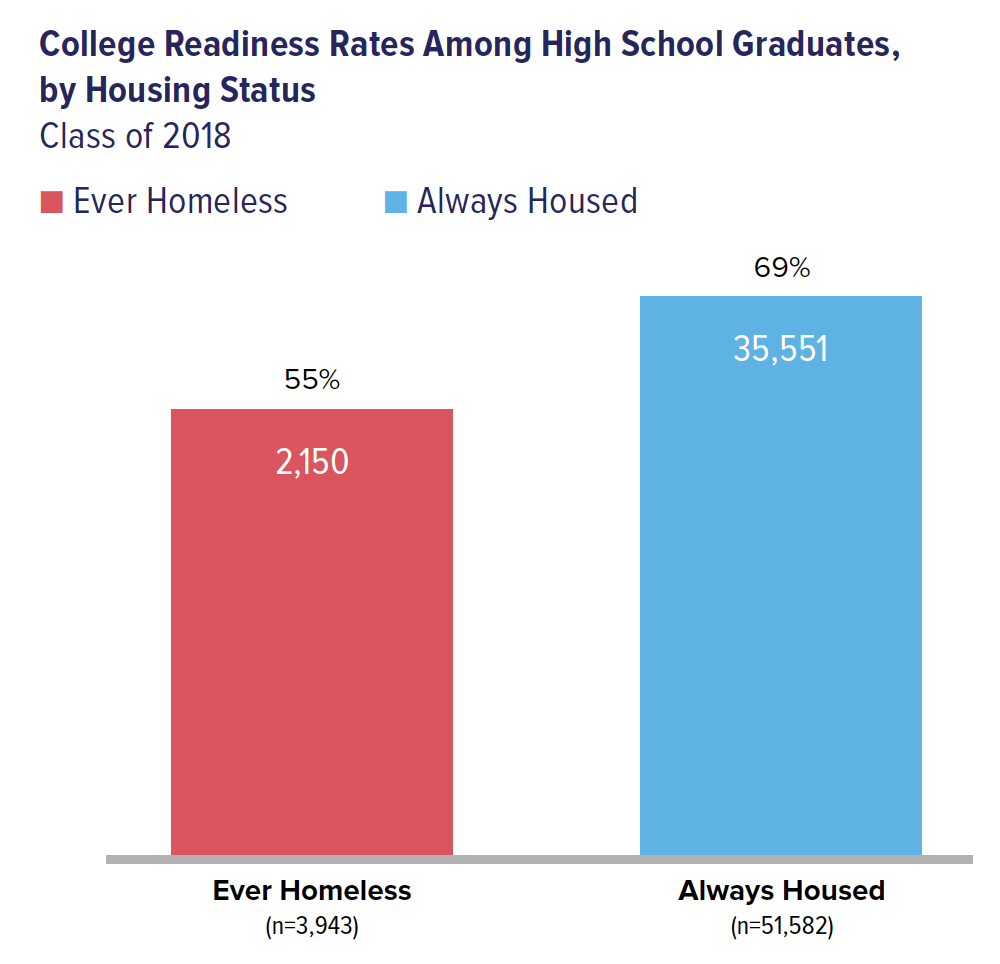

Of the over 7,000 students in the class of 2018 who experienced homelessness during high school, 59% graduated on time. Furthermore, only slightly more than 2,000 of these students met the New York City Department of Education’s (DOE) college readiness standards. This means that nearly half (45%) of New York City graduates who experienced homelessness during high school finished school not prepared to go on to college. According to the DOE, these students have not demonstrated, through their performance on standardized tests, the ability to handle college coursework and would require remedial classes prior to college. The financial burden and time commitment of taking these additional courses may function as a disincentive to continuing on to higher education.

While much can be done to support the education of homeless high schoolers, the challenges to being prepared for college coursework begin before high school. Disparities in educational achievement between homeless and housed students can be seen as soon as students begin to take standardized assessments in third grade and persist throughout the course of their education. Understanding why and to what extent homeless students are not prepared for higher education is a necessary first step to identifying the knowledge and skills they need for college.

Key Terms

Ever Homeless:

Students who were in temporary housing at any point during the school year, from SY 2014–15 to SY 2017–18.

Always Housed:

Students who were never in temporary housing during any school year, from SY 2014–15 to SY 2017–18.

College Ready:

Students who graduate high school and are prepared to take and pass college-level coursework.

On Time Graduation Rate:

The percentage of high school students who first entered ninth grade in SY 2014–15 and who graduated with a Local, Regents, or Advanced Regents Diploma in 2018. Graduation rates reported in this publication are for August and include summer graduates.

This report uses DOE data from all New York City public school students in the class of 2018. This report explores what it means to be college ready, and whether homeless students who graduate from NYC Public Schools are as likely to be college ready as their permanently housed peers.

What Does It Really Mean For Students To Be College Ready?

College readiness has many definitions that vary across cities and states. In New York City, the DOE has created the College Readiness Index, which defines college readiness as the ability to take coursework at the City University of New York (CUNY) without requiring remedial courses in math or English. To be college ready, high school students must graduate with either a Local Diploma or Regents Diploma and meet certain score requirements on the SAT, ACT, or Regents exams. Students can earn the different types of diploma based on the number of Regents exams they pass and the scores they receive.1

Are Homeless Students College Ready?

Among students in the class of 2018, more than 7,000 students experienced homelessness during high school— 9% of the entire class. In addition to having lower on-time graduation rates than their housed classmates (59% vs. 78%), these students were far less likely to meet the DOE’s college readiness criteria.

Among those homeless students who were able to graduate (and for whom college readiness data were available), only 55% met the City’s college readiness standards. By comparison, 69% of graduates who did not experience homelessness in high school qualified as college ready and would not be required to complete remedial coursework in college.

The DOE’s College Readiness Index measures whether students graduated with a Local Diploma, Regents Diploma, or Advanced Regents Diploma and met the City University of New York’s (CUNY) requirements for placing out of remedial coursework in English and math.

How Do Homeless Students Perform on Standardized Tests?

Regents Exams

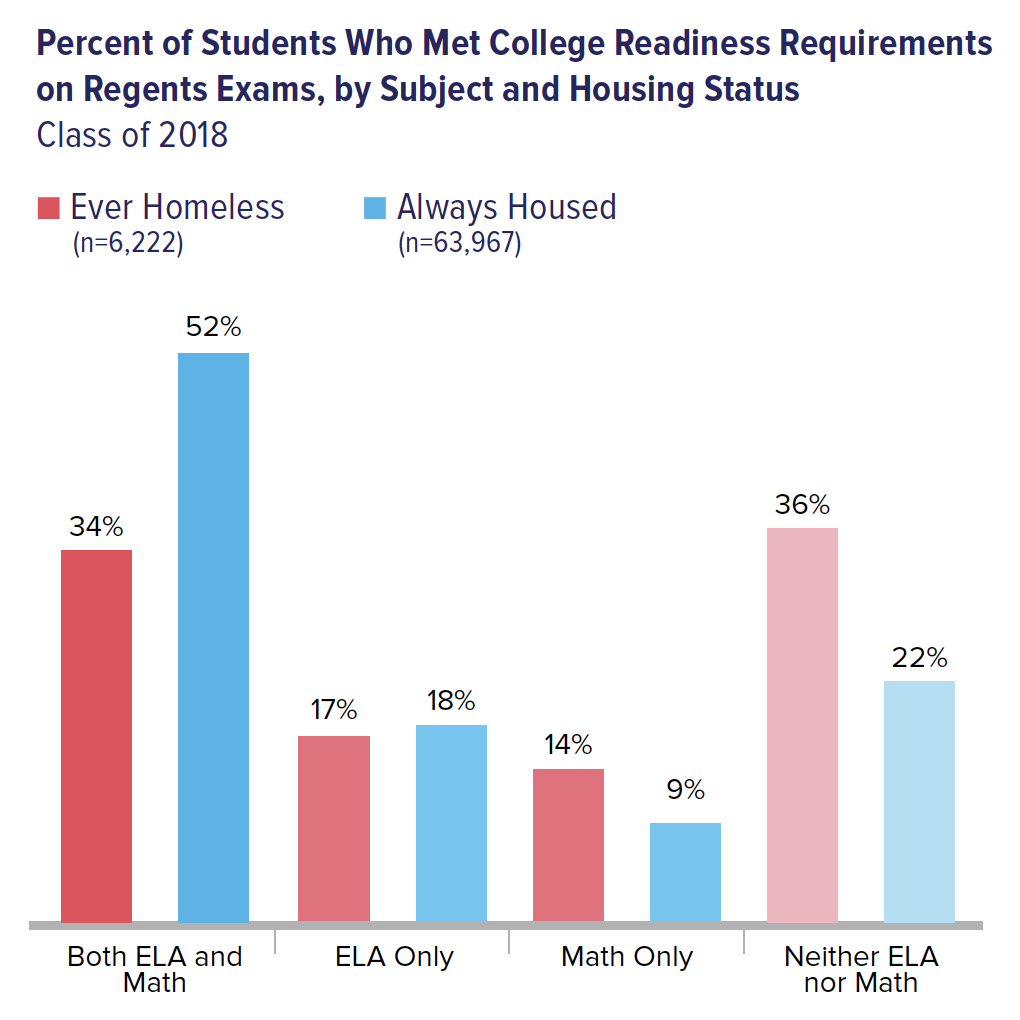

Students may prove readiness in English and math through scores on state standardized tests called Regents exams. On the Regents exams, only one-third (34%) of homeless students were able to meet college readiness standards in both English Language Arts (ELA) and math, compared to over half (52%) of housed students. At the same time, homeless students were more than 1.6 times as likely as housed students to not meet these standards on either the ELA or math Regent exams (36% vs. 22%). Students who only meet the college readiness standard in one subject would need to either retake the exam or meet the standard another way, such as with a qualifying SAT score. If the students cannot meet the college readiness standard, they would have to take remedial courses prior to or alongside college classes.

The disparities in Regents scores between students who experienced homelessness and those who did not are present before students enter high school. On the annual statewide assessments given in grades 3–8, homeless students were only about half as likely as housed students to score proficient in math (20% vs. 40%) and English Language Arts (23% vs. 43%).

As part of its College Access for All initiative, the DOE offers SAT School Day, when high school juniors can take the SAT for free during a school day—increasing participation for students who are not able to afford the fee to take the SAT exam, travel to an SAT testing site, or have other obligations that make the normal Saturday exam infeasible.

SAT Exams

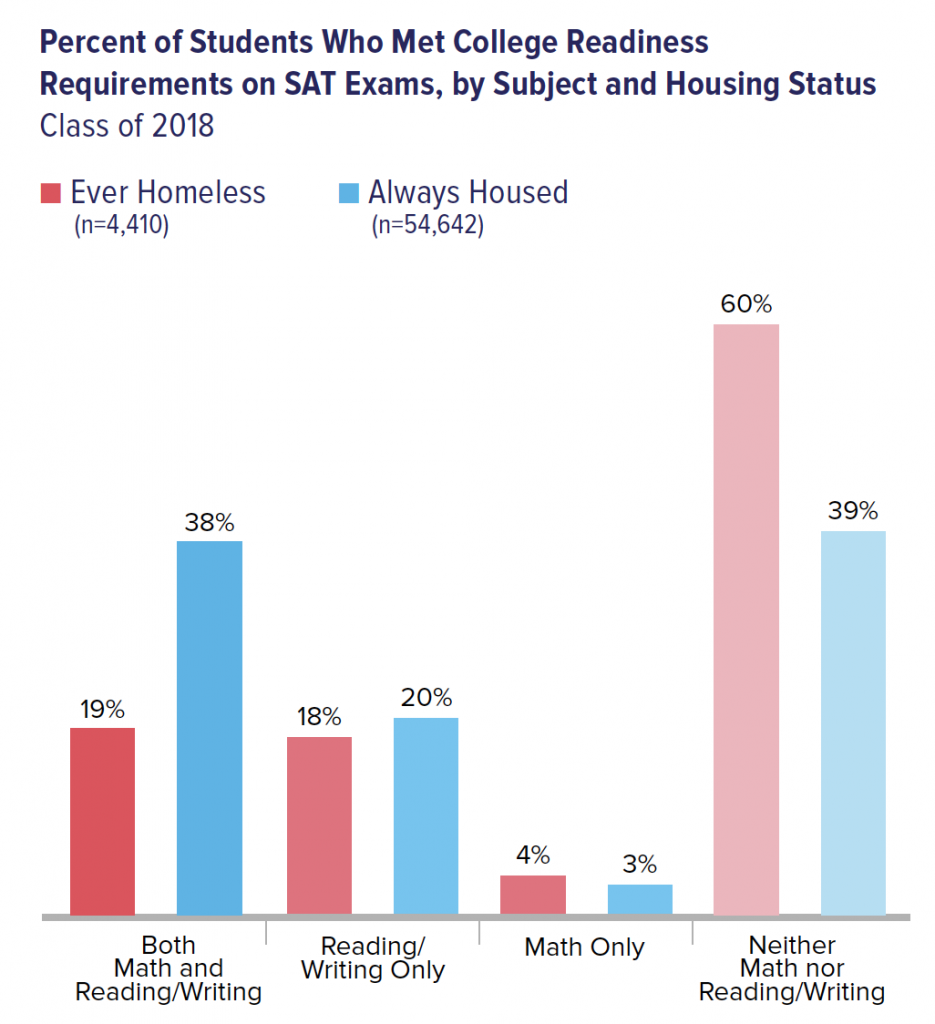

Students may also satisfy the DOE’s college readiness standards using their scores on the SAT, the standardized exam used by most colleges and universities to assess student aptitude. Overall, students were far less likely to meet the college readiness standards on the SAT than on the Regents exams, though trends among homeless and housed students remained similar. Homeless students were only half as likely to meet the SAT college readiness standards in both reading/writing and math compared to housed students (19% vs. 38%). One factor possibly driving this disparity is the number of times students took the exam: less than one-third (30%) of homeless students took the SAT more than once, compared to nearly half (47%) of housed students. Multiple test attempts often result in higher scores, as students gain practice and familiarity with each test.

How Do Homeless Students Perform in Advanced Placement Classes?

Standardized testing, such as the Regents or SAT exams, can be a limited indicator of a student’s ability to handle college coursework, especially for those who do not perform well on tests or who lack access to test preparation resources. Aside from the official College Readiness Index, another common indicator of a student’s preparedness for higher education is performance in rigorous classes such as Advanced Placement (AP) courses, which are designed to be at the same level as introductory college coursework. The courses culminate in an optional AP exam that students can pay to take at the end of the school year, in which students who pass with a three or higher on a five-point scale can earn college credits.2

Key Terms

Regents Exams:

Exams that measure student achievement in high school-level courses in New York State. Students typically take the exams in grades 9–12 and are generally required to pass at least five Regents exams in core subject areas to graduate high school. The score threshold for Regents exams to be counted toward a student’s college readiness are typically higher than what is required for graduation.

SAT:

Administered by the College Board, the SAT is used by most colleges to measure a student’s readiness for college. The exam includes two required sections (math and evidence-based reading and writing) and an optional essay section.

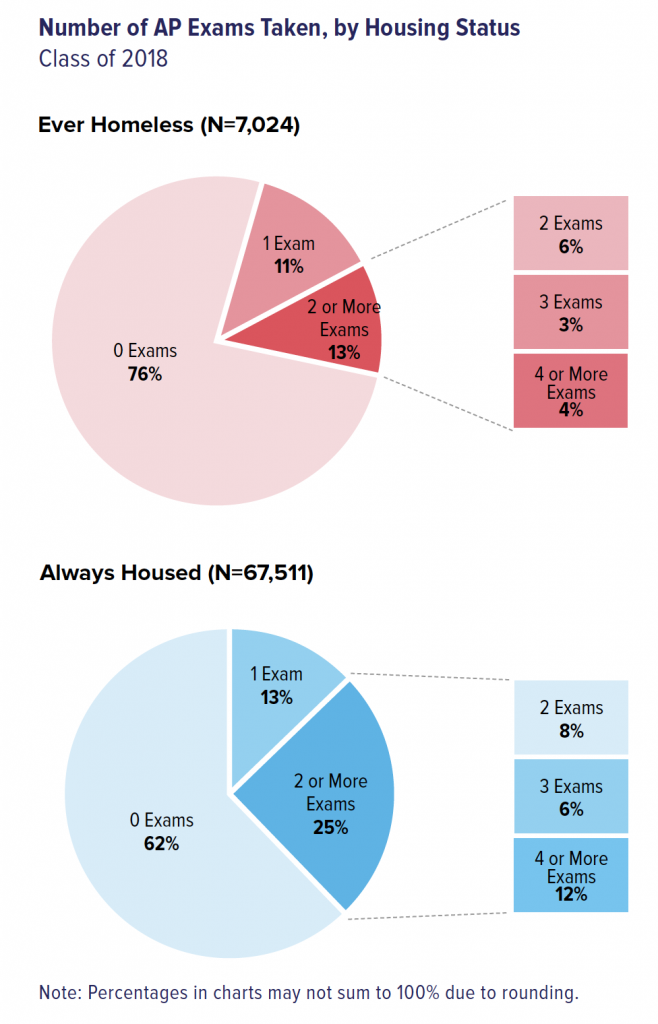

Homeless students are not, however, taking AP exams with the same frequency as their housed peers. Three in four (76%) students who experienced homelessness in high school did not take any AP exams, compared to 62% of students who were always housed. Only 13% of homeless students took two or more AP exams, roughly half the percentage of housed students (25%), and homeless students were three times less likely to take four or more AP exams (4% vs. 12%). These disparities may indicate that homeless students are not taking exams in AP classes they are enrolled in, have fewer AP course offerings in high schools that disproportionately serve homeless students, or a lack of educational supports that would help prepare homeless students for advanced coursework.

Students who experienced homelessness in high school were more likely to attend a school that offered no AP courses compared to students who were always housed (19% vs. 12%). At the same time, homeless students were far less likely to attend a school that offered a variety of AP courses (six or more) than housed students (34% vs. 53%).

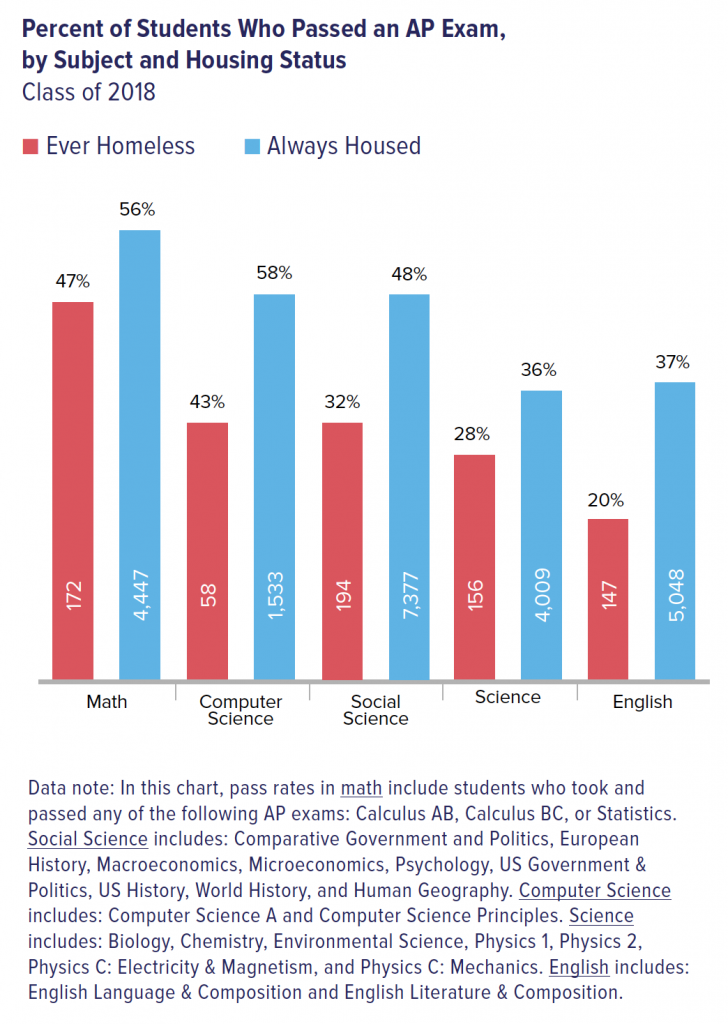

Across all subject areas, homeless students who took AP exams were less likely to pass them than their housed classmates, though the discrepancy varied by subject. Close to a third of both housed and homeless students who took an AP science exam were able to pass it, though the rate for homeless students was still significantly lower (28% vs. 36%). By contrast, homeless students were only about half as likely as housed students to pass the AP exam in either English Literature or Language and Composition.

New York City’s AP for All initiative aims to increase the availability of Advanced Placement (AP) courses to all high school students, with the goal of all students having access to at least five AP courses by 2021.

Increasing College Readiness for Homeless High School Students is Paramount

Ensuring that homeless students are able to succeed in high school and beyond requires that greater attention be given to the ways that housing instability creates academic disparities throughout a student’s education. This includes addressing the reasons homeless students often fall behind in their learning, which can be traced back to a student’s early school years—the compounding effects of chronic absenteeism, midyear transfers, late identification of additional education needs, and mental and physical health issues such as depression or asthma on academic performance. Homeless students, especially those who experience frequent chronic absenteeism and school transfers, often do not have an opportunity to catch back up to classmates and perform at grade level even after they return to permanent housing. This makes them less likely to graduate or be prepared for college-level coursework.

For homeless students in high school, support means addressing the systemic barriers that prevent these students from having the same opportunities for higher education as their peers. Although housing instability can set students behind in their learning, those who are still able to excel may be limited by the number of advanced courses offered at their school, their ability to afford multiple SAT attempts, or access to test-prep services.

In addition to DOE initiatives such as AP For All and College Access For All that are designed to improve college readiness for all students, it is imperative that homeless students have access to targeted services that can accommodate their needs, whether it is shelter-based tutoring, transportation to schools that provide advanced coursework, or other supports that are tailored to these students’ circumstances. By providing these enhanced services and tools, schools can help ensure that homeless students are able to graduate and reap the benefits of higher education.

1 Students are automatically deemed college ready if they earned an Advanced Regents Diploma or an Associate’s degree at time of high school graduation. ACT data is not available.

2Some colleges require students to earn a score of four or five to receive college credits.

Ralph da Costa Nunez, PhD, President & CEO

Aurora Zepeda, Chief Operating Officer

Andrea Pizano, Chief of Policy Research

Josef Kannegaard, Principal Policy Analyst

Amanda Ragnauth, Senior Policy Analyst

Katie Puello, Director of Communications

Hellen Gaudence, Senior Graphic Designer