Emerging trends from New York City

February 2012

Introduction

Family homelessness services in New York City have existed in different forms for over a century, but it is only in the last three decades that we have seen a more systematic response to serving the needs of homeless families from the New York City government. The creation of Tier II shelters beginning in the late 1980s and the formation of the Department of Homeless Services (DHS) in 1993 put the City at the forefront of addressing family homelessness. The creation of the Tier II model, a combination of emergency and transitional housing, has been a helpful way out of poverty for many families.

Between 2008 and 2010, average lengths of stay in the shelter system dropped from 11 months to eight months. This is a testament to the positive work that has been done to better match families with the services that they need. We know much more about homeless families now and the reasons that they become homeless.

While still complicated, we know that families become homeless for different reasons, but that they can often be identified as families who are experiencing different kinds of poverty: situational poverty and generational poverty. Situational poverty is created by an event or temporary condition that impacts a family, i.e. job loss, divorce, or illness. These are families for whom a brief stay in a shelter, along with the minimal attending services, is what they need to regroup and regain permanent housing.

However, with a recidivism rate of almost 50%, it has become obvious that there are a number of families for whom the current system is a failure, much like many of the other public systems that these families have encountered.1 These families with children are, for all intents and purposes, chronically homeless, whether or not they are in the formal shelter system. This group of families that are served repeatedly by the homelessness services system often come from generational poverty situations, and have greater needs and challenges to being able to obtain and maintain permanent housing and create safe, stable, thriving households for themselves and their children, thereby moving into the middle class.

Research over the years has shown that these families often have a variety of different types of needs and challenges to stability. Little or no educational attainment or work histories, domestic violence, physical and mental health concerns, involvement with child welfare agencies, and even substance abuse are all obstacles that these families face. A comprehensive, intensive program that helps them address their own needs and concerns is what they have lacked. These are families who have likely never known anything but poverty, and for whom it is much more of a struggle to gain the skills and education needed to reach the middle class.

Unfortunately, the current system of services for these homeless families does not serve the long-term needs that they have. They have challenges and problems that need more than a month of time to successfully address. While these families do not need a lifetime of supportive services such as those offered by supportive housing models, they could greatly benefit from a transitional/temporary program that could offer them a stable, supportive environment that will help them to achieve the goals they have for themselves and their children, including a good job and a home of their own.

What can be done to address the needs of these particular families?

In order to address these needs, the Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness (ICPH) has created a vision of a new path to stability for these families, informed by research on family dynamics, the impacts of trauma, and years of experience and reflections from service providers both here and around the country. For years, the New York City system of family homeless services had only a front door and a back door. This new system proposes a true pathway for families to follow to move from homelessness to stability and health, while still keeping in mind the priorities and requirements of the current systems, City departments, and the political climate. While a utopian vision of homeless services is fairly easy to craft, it is much harder to envision a system that utilizes the tools already in place and working for some families, while also putting into place additions that will address the needs of the chronically homeless and those living in generational poverty.

With this in mind, ICPH is proposing herein changes not only to the public systems that interact with homeless families and children in New York City, but also to the programs that help them reach their goals. We are proposing various degrees of change—some fairly mild, and others fairly radical. The end goal of all of these proposed changes is to improve the way that public funds and systems are used to serve those most in need, by those most able to do so.

Proposed systems changes include:

- Revamping of the system for targeting shelter services to families, especially as concerns eligibility determination and conditional placements (see Tier I: “Allocating Resources According to Identified Needs”)

- Approval of time-limited specialized programs for families (see Tier III: “Offering Families Real Opportunities to Create Their Own Futures”)

- Prioritization for the allocation of subsidized housing

Proposed program changes include:

- Retooling of family assessments while in emergency (conditional) shelter placements

- Creation of Tier III Community Residential Resource Centers with specialized services for families with specific needs

xxx

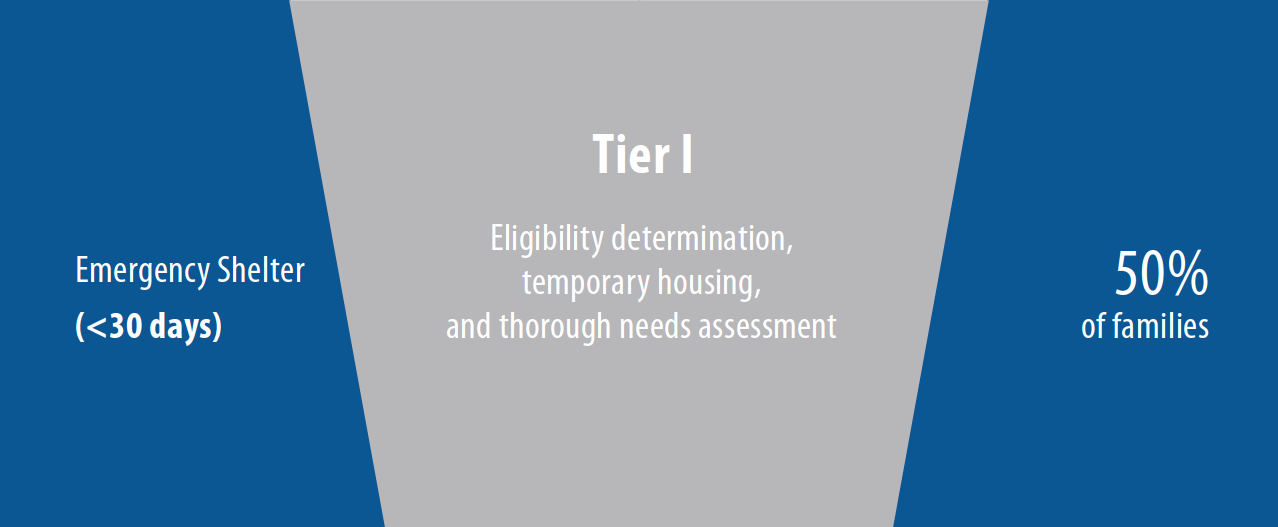

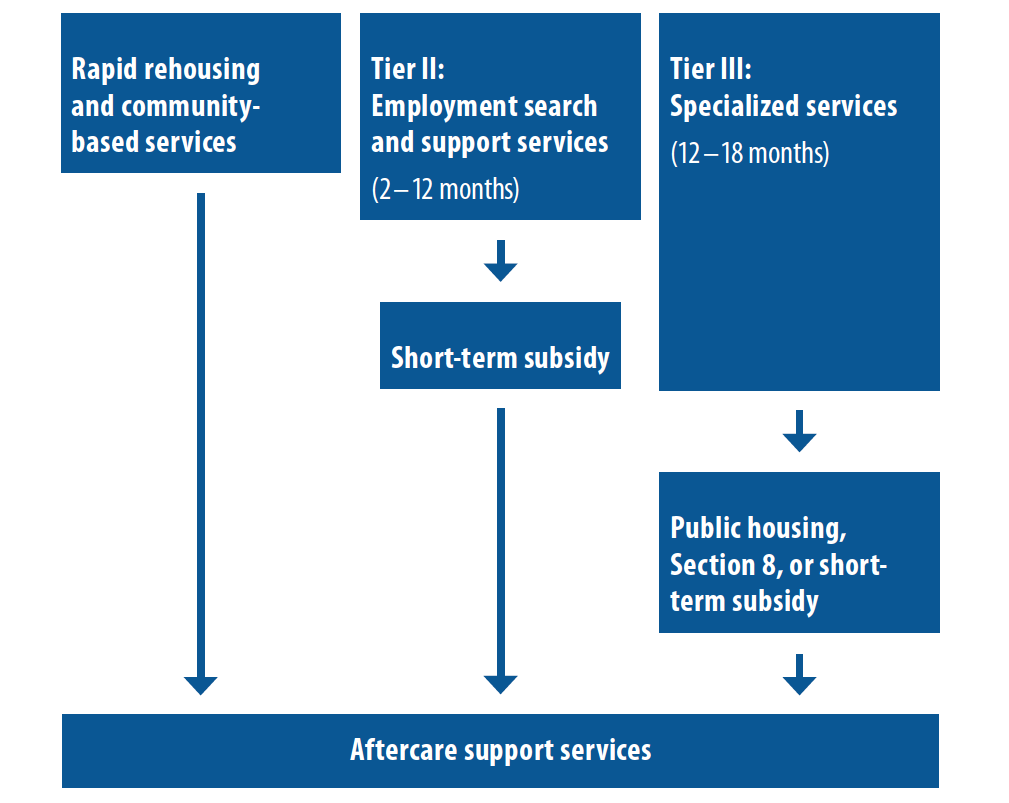

ICPH is proposing a three-tier system of shelter services for families:

Tier I: Emergency Shelter Stays

This tier looks almost identical to the current system of services for families who enter the Prevention Assistance and Temporary Housing (PATH) Office. Almost half of the families who are placed in a shelter leave within 30 days. These families need (at the time) only a short stay in a shelter. Some of these families never return to the system; others have cycled in and out. It is these families who cycle in and out of the system that this new proposal would address.

Assessment

During the first 30 days that a family lives in a shelter, the case managers will have a chance to meet the family, get to know them, and begin to help them to address their needs. While 30 days is not enough to build up the trust and relationships between families and staff members that are required to make real, long-term changes, it is enough time for a needs assessment and initial goal plan to be created as a blueprint for future activities. It will be during this period that a family, working with shelter staff, can determine what programs are available that would best suit the goals identified by the family.

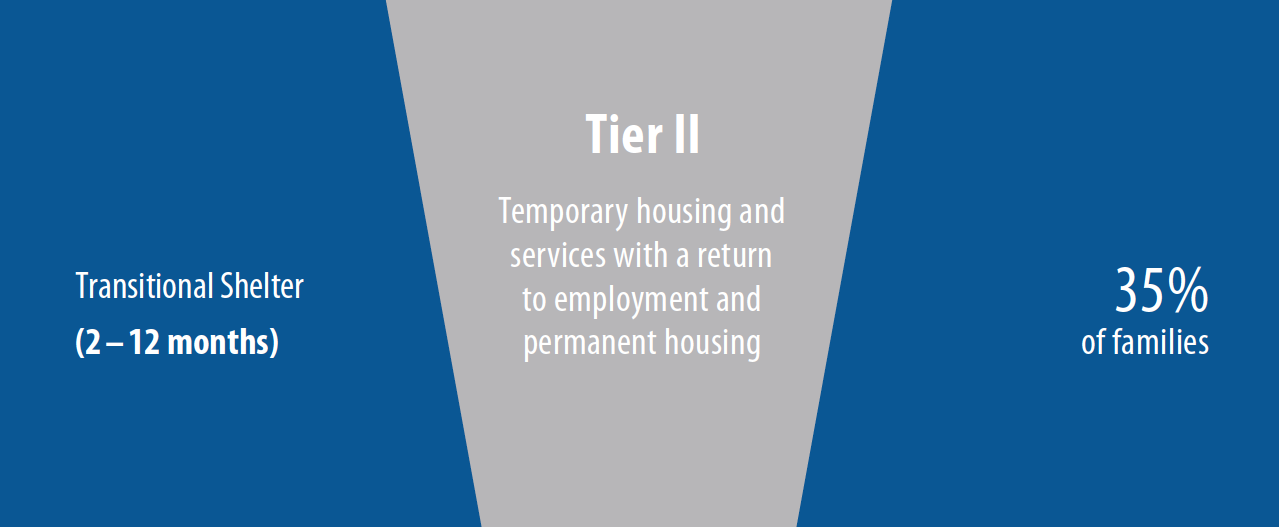

Tier II: Transitional Shelter Stays

This tier also looks almost identical to the current system. These families who enter the system stay for between two and 12 months. Most of these heads of household have some sort of education and work histories, and need help getting back on their feet and securing housing. These families are served well by the current system of family case managers and housing specialists in finding new or better employment and affordable, market-rate housing. They do not usually return to the shelter system.

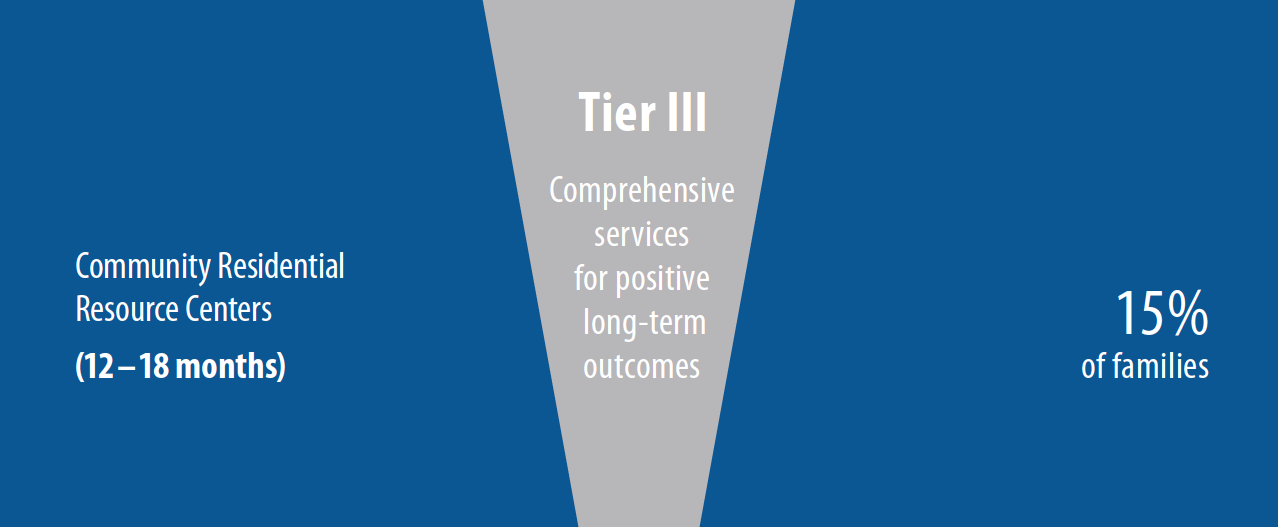

Tier III: Specialized Shelter Programs

Families who identify more complex needs and have higher barriers to maintaining permanent housing would be eligible for a specific type of shelter program, which would be called a Tier III program, or a Community Residential Resource Center (CRRC). Tier III CRRC programs would be specialized programs designed with specific outcomes identified. Tier III CRRC programs would focus intensively on education and employment, as well as domestic violence and child abuse/neglect prevention, and substance abuse treatment as needed. Each of these models is described in more detail in the following pages.

This model grew out of experience showing that parents generally want to get a job and maintain a household. Parents want to do this, but it can be almost impossible to focus on educational pursuits and creating a healthy family environment when they face the constant day-to-day pressure from public systems to get a job, find an apartment, and move out of the shelter. Those coming from generational poverty may lack the skills and knowledge and social connections/support needed to move their families into the middle class. This revolving door of homelessness leads to poor outcomes especially for the children, who are forced to change schools and who themselves are unable to focus on their educations. Without an education and a stable, healthy family, the type of jobs that parents have access to will ensure that families remain a drain on the public assistance system, rather than a net gain to society.

For a specific group of families, access to education, employment, and healthy family services while living in a structured, goal-focused environment can be the solution. This program would be similar to other types of community settings in which people have common goals and characteristics—retirement communities, religious communities, and educational communities such as on-campus student housing. The stability created by these communities allows each group to focus on the task at hand without the day-to-day worries that can so quickly become the reason to quit.

It is important to remember that the program(s) described here are not meant to be a solution for every homeless family that arrives at the Department of Homeless Services’ intake center. This model is meant to address a specific subset within that group who have a prescribed set of characteristics. Families who choose to participate in the program will work in partnership with program staff to meet their goals, achieve program outcomes, and prepare themselves for life after the program. They will be able to do so, however, without having to worry about whether or not they will lose their place because they missed a meeting or a deadline. Make no mistake—this is a program in which families are expected to be full partners and meet defined goals. But the program is designed to help them do that, rather than punish them for missteps along the way.

There are still consequences for not fulfilling goals and requirements, but there is a process in place that recognizes the positive long-term impact as compared to the negative short-term hiccups. If stable housing, a general equivalency degree (GED), a job, and a stable, healthy family are not the first goals that a family wants to address, these will not be the programs for them. Families who prefer not to complete their Tier III programs will be referred back to the Tier II system, as appropriate. The Tier III programs fit comfortably and logically along the current continuum of shelter focused human services that include a range of service intensities, from emergency shelter to permanent supportive housing.

Housing Options

The tools available to address the needs of families experiencing homelessness in New York City have changed drastically over the past five years. Rental assistance and housing programs such as Section 8, Advantage, and Mitchell Lama, which once served to make housing in New York City affordable even for poor and lower-income families, have all disappeared or been reduced substantially. Some families, especially those with some level of education and employment histories, are able to move into market housing, or at least affordable, market-rate housing. However, families who complete Tier III programs will still be fragile as they exit the program (although aftercare services will be available). As they have made the commitment to complete the Tier III program, the City should honor that commitment with housing assistance. As there are no rental assistance programs on the fiscal horizon, the City must prioritize subsidized housing for families who complete the Tier III programs described in the following pages.

The changes that are proposed within this document address not only the programmatic changes that service providers could implement to better serve families, but also the systematic changes that are needed within government agencies in order to allow service providers to work with families more effectively. In part this will require a recognition by everyone involved that homelessness services are often the last resort for families who have been failed by the other public systems that have touched their lives—education, child welfare, physical and mental health care (including substance abuse), public assistance, and so on. If we do not help families in life-changing ways at this point, then services are at best a temporary bandage to cover the gaping wound of poverty and at worst a moral failing of our society, which claims to value the equality of opportunity for everyone. We must also recognize that the system of services as it is currently set up is designed to meet the needs of families as identified by the system, rather than those identified by the family itself. Strengths-based, family-focused, trauma-informed systems work in other places, and any excuse not to offer the same service model to families is simply unfair, ineffective, and expensive.

Endnote

1 Coalition for the Homeless, Forty-one Thousand: As Mayor Bloomberg’s Failed Policies Exacerbate Crisis, NYC Homeless Shelter Population Tops 41,000 People Per Night for First Time Ever, November 2011.

xxx

CHAPTER 1—A Third Tier:

The Next Step Forward

New York City needs a new plan for homeless families: not a plan to end homelessness based on unrealistic expectations, but one based on experience that can begin to reduce homelessness right now. The city has confronted this epidemic for years and has gained invaluable knowledge about what does and does not work. The answers are right in front of us in the form of existing infrastructure and experienced and dedicated personnel. We need only acknowledge what has worked in the past and continue to build on prior successes while simultaneously acknowledging past failures and steering clear of previously identified pitfalls.

One Size Does Not Fit All

Homelessness can undoubtedly be a housing problem. But to stop there is to cut the analysis short and to drastically oversimplify the obstacles faced by many homeless families. Diverse factors contribute to housing instability. The path to housing stability can be just as varied. Homeless families often face additional obstacles to education, work, child care, safety, and health.1 Effectively addressing these problems is central to a lasting resolution of their immediate housing crises. Over the past decade, however, the substantial needs of homeless families have been obscured by an increasingly single-minded focus on rapid rehousing initiatives.2 Simultaneously, the services originally designed to target the significant obstacles faced by homeless families were gradually being eliminated.3

Common sense tells us a differentiated approach to the problem of family homelessness is essential if real progress is to be made for future generations of New Yorkers. To help families move toward growing stability, the weight of the underlying problems faced by these families must be acknowledged and addressed. Beyond mere rent subsidies, targeted support services can help homeless families develop new strengths and skill sets in those aspects of their lives that most contribute to their stability. To deemphasize these critical services is to forego critical opportunities for putting families on a long-term path toward stable housing.

A New Look at a Multi-Tier System

The current emergency housing system is centered on Tier II residences, a terminology developed in times when Tier I facilities were still in use. The original Tier I facilities were congregate shelters, and were eliminated from the family shelter system for multiple reasons, not the least of which was the lack of privacy such facilities offered families. The old tiered system was based on the quality of the facility, with the lesser quality congregate shelters on the lower rung and the facilities offering private family accommodations on the upper Tier II rung.

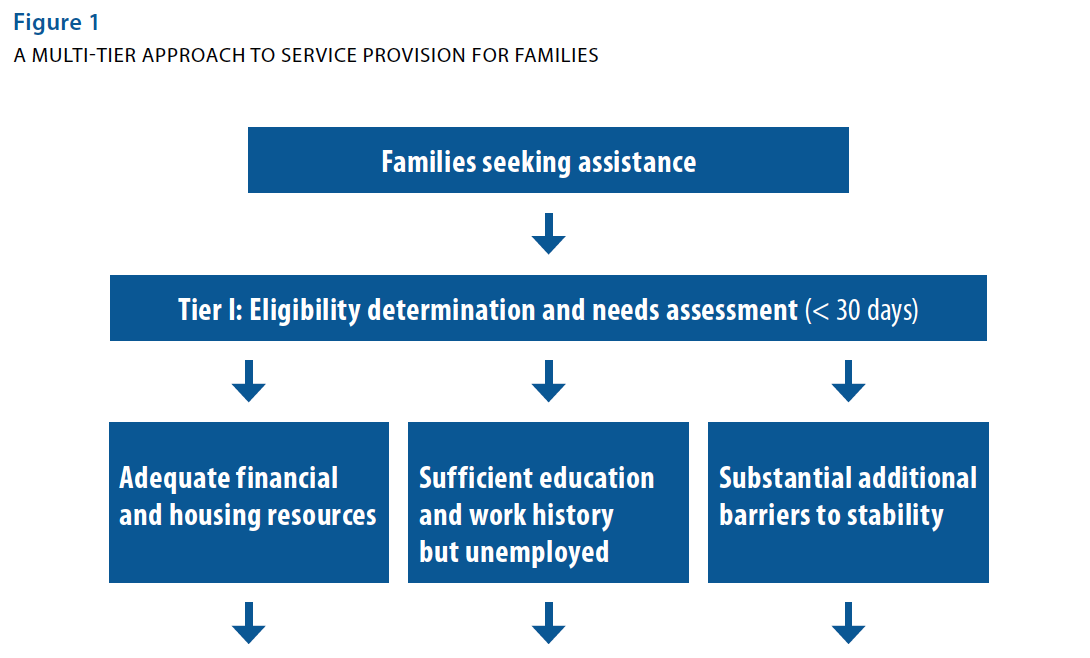

A rethinking of the tiered system as displayed in Figure 1, based on varying levels of family need, promises to be a worthwhile response to the recent “one size fits all” rapid rehousing approach. The City’s recent experiment with short-term subsidies (not to mention decades of shelter trend data) has shown that families experiencing housing crises have widely divergent service needs.

Some families, with more extensive personal and social resources, are in need of only very short term assistance of a month or less.4 Other families, whose immediate housing crises can be framed in terms of situational poverty (unexpected financial obligations or loss of employment), can often regain their footing over a matter of months with only minimal outside intervention.5 Yet, there are also those families with more significant barriers to housing stability. Some caught in the throes of generational poverty lack sufficient education or work experience, while others face more immediate health and safety risks as a result of domestic violence, child welfare issues, or mental health and substance abuse issues.6 The significantly greater obstacles faced by these families will necessarily correspond to longer paths to stability.

In the interest of families in need and the system as a whole, it makes sense to structure the emergency housing system according to these evident varying levels of need. Central to this proposal, then, is a refined system of multi-tier services. Tier I will address the most immediate housing needs of families applying for assistance. For many families, a month or less of assistance at Tier I will prove sufficient to help them reestablish housing. Those families who, during Tier I placement, present a need for additional, but still moderate, support will access Tier II services. For most of the families in the Tier II category, roughly six months of assistance will be adequate to meet their needs. Families who identify the greatest service needs during the initial intake and placement will be offered the opportunity to enroll in a Tier III program, through which they will receive support over the course of 12 to 18 months in core service areas (employment, education, domestic violence, child welfare, mental health, and substance abuse) according to their identified need.

Tier I: Allocating Resources According to Identified Needs

In a system of tiered residences, families will initially be assigned to a 30-day conditional placement. During this time, as in the current system, a field investigation will be conducted to determine the availability of other housing options, but the final eligibility determination will be equally informed by an assessment of family needs and strengths conducted by the social services staff at the conditional placement site.

Streamlining the application process

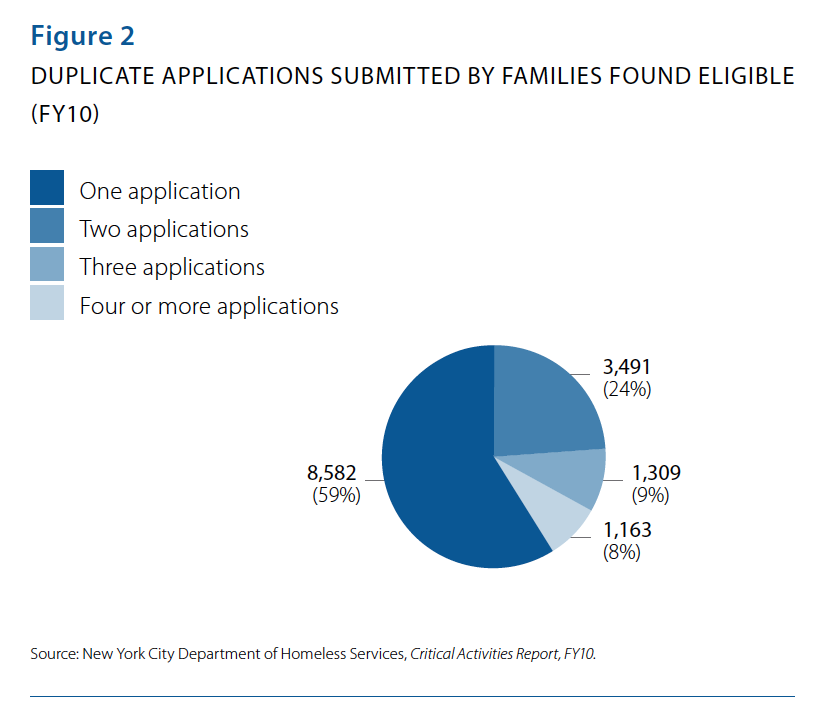

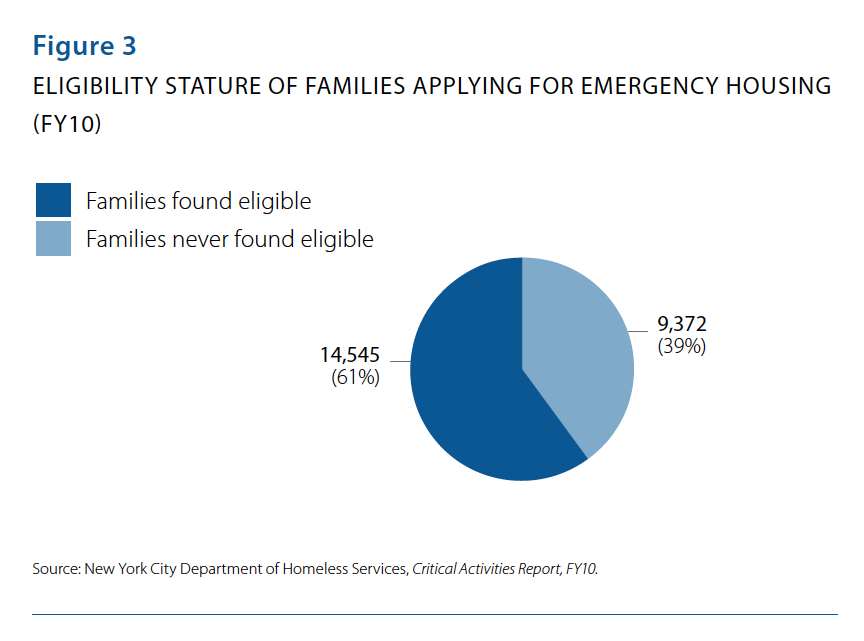

In the current system, conditional placements are limited to ten days, but data show that this is insufficient time to accurately determine eligibility. That is, of all families eventually found eligible for shelter, less than 60% are found eligible on their first application.7 One-third of all families eventually found eligible must submit two or three applications before receiving a favorable determination. This means these families cycle through conditional placement for 2 –30 days before being found eligible.

This duplication of effort during the intake process is taxing not only to families in crisis but also to the system as a whole. With multiple mandatory housing transfers and several days lost to the application process, families are made susceptible to further destabilization through the intake process as it stands. And the existing process means PATH intake workers must complete assessments multiple times for one family over the course of a month. For housing operators, it means over one-third of all new intakes are families cycling through the application process. This translates to wasted time and money for housing operators who must accommodate a much higher initial turnover rate, requiring more staff to repeatedly prepare rooms for occupancy and file required paperwork that was most often already completed once or twice before within the span of ten or 20 days.

Increasing the accuracy of eligibility investigations

The proposed 30-day conditional placement will be housed in designated facilities uniquely structured to accommodate this period of service delivery that is high-demand for families and providers alike. Extending the term of the conditional placement will help improve the accuracy of eligibility determinations, affording families greater stability in the process. Retooling an adequate number of facilities to focus exclusively on the specific application requirements unique to the conditional-placement phase will help streamline the process for both families and providers. Investigation staff located on site will have ready access to the families with whom they need to meet, eliminating the need for families to shuttle back and forth to PATH during the investigation phase of the application process, an unnecessary travel burden that ultimately results in missed appointments and inaccuracies in eligibility determinations.

Determining the level of assistance through a thorough assessment of needs

Social service staff concentrating exclusively on assessment of family needs and strengths will be better positioned to help families critically evaluate their own circumstances. By specializing in assessment, social service staff will master effective use of assessment tools and techniques. In this way, the assessment process will offer families the opportunity to identify the particular factors that contributed to their immediate housing crisis. At the same time, the assessment will help bring to light identifiable family strengths that emerged as resources through the course of the crisis. Through the process of Tier I assessment, it will become evident which families have the capacity for rapid return to the community, which would benefit from slightly more support through Tier II residences, and which should be offered the opportunity to enroll in the intensive services of Tier III residences.

Targeting prevention strategies as a critical time intervention

This reorganization offers another significant upside: It will prove a better solution for the thousands of families each year who apply for shelter but are never found eligible.8 Incorporating a more thorough needs-and-strengths assessment into the conditional-placement program model will help families identify existing resources to facilitate timely rehousing in the community. In this way, if field investigation teams determine families have alternate housing options available, social work assessment teams will have already uncovered and discussed these options with families, helping them to navigate any outstanding obstacles preventing them from accessing these resources. For those families with the documented financial capacity to secure their own apartment, financial aid in the form of relocation assistance will help expedite the process. Through these efforts, ineligibility for emergency housing will cease to be an additional crisis to be faced by families. Rather, it will become an opportunity to tap available resources through the help of professional staff well versed in both housing crises and the common solutions to such crises.

Linking families most in need to community-based services

Families capable of successfully returning to the community after only a brief intervention in Tier I conditional placement will also receive limited aftercare services, primarily through monthly telephone check-ins over the course of the first three months, to ensure ongoing stability and determine the need for any additional services. In this way, those families who have self-identified through their application for emergency housing as those most at risk of homelessness will be directed to community-based support services to help them move toward ever greater stability. As such, the tricky task of targeting services to those most in need will become less of a gamble and more of a scientific undertaking. This limited aftercare intervention will not only help link families most in need to critical services but will also allow the City to measure the success of community-based interventions.

Tier II—Helping Families Return to Work through Employment Search and Support Services

For those in need of slightly more support beyond Tier I, a host of employment search services and supplemental supports will be provided on site at Tier II residences. Structured on an average six month length of stay, Tier II residences will be best suited to the needs of those families who have attained, at minimum, a high school diploma or GED and who have some prior work history upon which to base an employment search.

Employment services

For those heads of household who are currently employed, but only minimally so, or those with substantial work histories who are currently unemployed, Tier II employment services will help them better leverage and build upon existing work histories and skill sets. These families will be immediately directed to intensive working sessions with employment specialists who will help heads of household connect with local employers. Assistance will be provided to tailor resumes and craft cover letters to match available positions. Interviewing techniques and strategies will be polished in individual and group sessions.9

Child care, after-school programs, and medical services

On-site child care services and after-school programs will not only contribute to the development and academic achievement of children but will also help free time for heads of household to navigate critical obstacles central to the family’s overall stability. Medical services will be provided in-house on a regular basis to help monitor family health and physical well-being.

Personal finance and benefit counseling

Families entering Tier II services will also receive budgeting assistance and financial counseling. Families will have the opportunity to develop a detailed budget itemizing all income and expenses, in this way helping families to recognize where costs can be cut and what steps need to be taken on a daily basis to maintain solvency. At the same time, financial counselors will help ensure families are receiving all the benefits for which they are eligible (including SNAP, WIC, EITC, and child care), thereby maximizing the total household income.

Transitional housing benefits and aftercare services

It is expected that those entering Tier II services, once fully employed, will be able to secure housing on their own with only moderate financial aid in terms of relocation assistance or a short-term subsidy not to exceed six months. Given the limited duration of such a subsidy, it is not to be seen as an answer to an existing housing crisis but rather as a transitional benefit targeted to those with a documented financial capacity to manage future expenses independently. To monitor their transition to housing stability and provide referrals for any identified service needs, these families will receive monthly follow-up phone calls for the initial six months after exiting Tier II housing. For those families still unable to secure adequate employment at the end of the six months, enrollment in more intensive Tier III services will be an option.

Tier III: Offering Families Real Opportunities to Create Their Own Futures

Though many families will be able to transition to stable housing through the limited intervention of either a Tier I or Tier II residence, other families facing more significant obstacles will benefit from the additional services offered in the up-to-18-month-long program of a Tier III residence. A portion of the homeless family population struggles with additional barriers to stability, including low educational achievement, minimal work experience, domestic violence and child welfare histories, and mental health and substance abuse issues.10 To the extent that these barriers are glossed over as inconsequential to the immediate housing crisis of homeless families, future family stability will always remain out of reach. Tier III residences will offer families the opportunity to directly address these primary barriers, helping them in the process pave the way to a better future. Capitalizing on the existing infrastructure and staff competencies of the current emergency housing system, strategic modification of the system will allow for efficient provision of core family services.

By creating an environment where exploration of such services is encouraged and supported, Community Residential Resource Centers will help homeless families identify additional needs that would help further their goal of housing stability if sufficiently addressed. A system not tooled to address such additional needs only forces families to conceal problems, fearful that airing such issues might make them ineligible for necessary housing benefits. The CRRC service model will foster an environment where families will be afforded a real opportunity to sort through and address the most urgent family needs.

Whereas other families with greater financial resources and social networks are better positioned to secure similar necessary core services with less outside support, provisions need to be put in place to afford less resourced families the same opportunities for advancement. The emergency housing system is well positioned to provide this support. With the primary obstacle of immediate housing addressed, families will have the stability necessary to focus their attention on other pressing matters, such as education and job training, or other more critical issues. At the same time, supplemental services provided by emergency housing operators, such as child care and after-school programs, will help further facilitate the movement of families from crisis to increasing stability. In this way, a better tomorrow for the next generation will become a real possibility, not a far-fetched dream. If the City’s poorest families are made to exist in basic survival mode at all times, their best plans for increasing family stability will be laid to waste, and generational advancement will be impossible. For the sake of the individuals and for the sake of the City, the poorest New Yorkers must be offered real opportunities. If emergency housing represents the last layer of the safety net (the catchment for families who have fallen through the gaps of mainstream services), then it must also be the place where previously missed opportunities are once again offered, this time with the support necessary to help families succeed.

Enrollment in Tier III residences will be based on primary service needs self-identified by families during the assessment phase of Tier I conditional placement. Enrollment in the targeted services of Tier III residences will be voluntary. Though much will be asked of these families in terms of active program participation, the potential gains for those sufficiently motivated will be significant, too. During the assessment phase of Tier I conditional placement, certain service needs will emerge as more pronounced and will serve as the basis for the core services of Tier III residences. Along with the following core services in five distinct program areas, each of the Tier III residences will also provide the same support services offered in Tier II residences, including child care, after-school programs, medical assistance, and financial counseling.

Community Residential Resource Centers

Advancing employment

Some families with adequate education will still be struggling as a result of limited or no work experience. Job-skill development, work experience opportunities, resume building, and interview preparation will be the program focus for such families in Tier III Advancing Employment Residences.

Furthering education

Other families might be operating at a deficit directly related to the lack of a high school diploma or GED. Educational advancement will be the primary objective of such families in a Tier III Furthering Education Residence.

Providing safety

Thousands of families with verified safety concerns related to domestic violence apply for emergency housing assistance each year but do not receive the necessary assistance due to the limited capacity of existing domestic violence shelters. Tier III Safety First Residences will help fill this critical gap.

Preserving families and child wellness

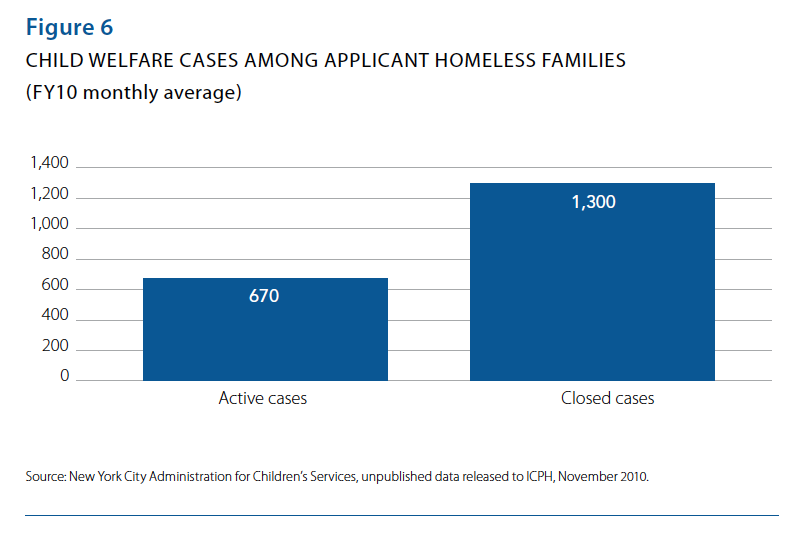

Hundreds of homeless families each month are identified with active child welfare cases, and even more with closed cases. At the same time, a major obstacle to family reunification for children in out-of-home care is housing instability of the family. Child well-being must be the focal point of all services provided to these families. Child safety in family preservation and the timeliness of family reunification will be the hallmarks of Tier III Child Wellness Residences.

Supporting mental health and recovery

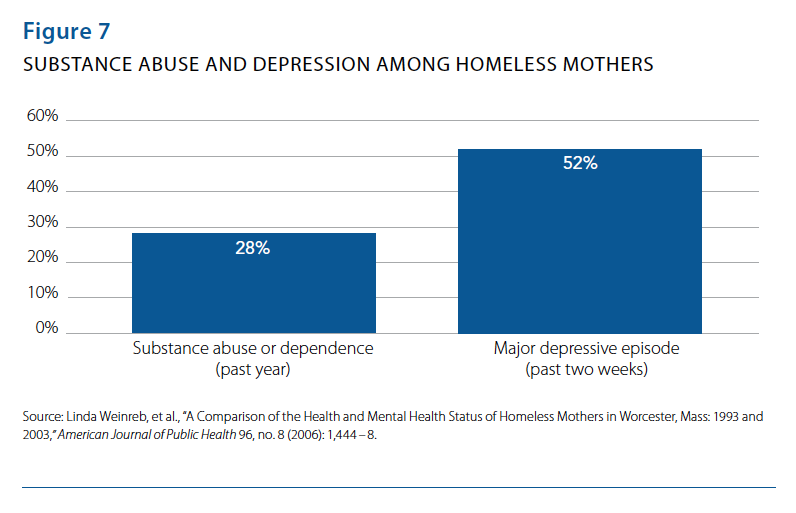

A number of families might present with histories of recent institutionalization stemming from mental health or substance abuse issues. Other families might reveal emerging crises in regard to these issues. These families will be offered enrollment in a Tier III Health and Recovery Residence.

Tier III: Community Residential Resource Center Key Features

Addressing multiple needs

Of course, some families will present with one or more of the core service needs. In such cases, safety concerns must take precedence. For instance, a family with substance abuse issues and an active child welfare case must prioritize the safety of the child. Such a family would be referred to a Child Wellness Program to help guarantee child safety. But the substance abuse problems of the family would be addressed, too, through collaboration with a nearby service provider, especially if located within another CRRC, where treatment would be obtained through outpatient services. Collaborative “in-network” service delivery will greatly streamline the process for both families and providers. Plus, service providers’ in-depth understanding of the particular obstacles faced by homeless families will help pave the way to improved outcomes for families. Even more, providing core services to both residents and those residing elsewhere will help providers maintain utilization rates sufficient to meet established cost margins.

Utilizing existing infrastructure

The community-based infrastructure for such collaborative service delivery already exists in the form of current emergency housing shelters. These shelters are already strategically positioned throughout the city in areas of greatest service need. By tailoring CRRCs in a particular geographic area to focus on different core service areas, a whole host of service needs common to homeless families could be made available through localized networks of Tier III CRRCs. Such strategic planning across the system will provide for more efficient utilization of existing physical and personnel resources, and the improved service delivery will have a noticeable effect on families and children in need.

Prioritizing public housing as a transitional benefit

Given the substantial service needs of families in Tier III CRRC programs, many will still require additional housing assistance in order to transition to their own home after completing the program. For these families, affordable housing resources must be leveraged to help them continue their transition to stable independent living. For instance, such families would be prime candidates for the City’s public housing residential employment program, where residents of public housing are prioritized for employment opportunities at public housing developments. This combination would provide the housing and employment transitional services necessary to help further advance the goals of those families exiting Tier III residences.

Reducing recidivism through continuity of aftercare services

As the existing shelter system begins to re-envision its potential to transform into localized networks of Tier III Community Residential Resource Centers strategically collaborating to provide core services to homeless families in need, the ideal of accessible and effective aftercare services finally becomes feasible. That is, the localized networks of Tier III CRRCs become community anchors providing critical services to those most in need. Families transitioning from a CRRC will still be able to receive in-office services as needed from the same providers they have grown to trust during their time in residence. The support system does not vanish with lease signing. Rather, key providers and services remain close at hand as a lifeline should future crises emerge. Even more, ongoing everyday support around child care, after-school programs, and future employment goals are readily accessible to families as they continue on their path to growing stability.

Extending support services to the broader community to help prevent homelessness

As Tier III support services become increasingly integrated into the local communities, the potential for truly neighborhood-tier prevention services will begin to emerge, too. Given that word of mouth is still the most effective marketing tool in the social service arena, families at risk of homelessness or simply in need of the services offered will learn from their neighbors that the first place to turn for help is the local Tier III CRRC. In this way, the integration of services into neighborhoods with the greatest need will help families long before homelessness threatens.

Capitalizing on peer support networks

The local community emphasis of Tier III CRRC programs will naturally lead to the development of peer support networks. Such networks, facilitated at the Tier III CRRC locations (perhaps even with moderate stipends for regular participants), will help strengthen final outcomes once families transition into their own apartments. In fact, such aftercare peer support groups can also serve as an outreach arm to those in need of prevention services in the community. After all, families who have experienced housing crises themselves will be able to easily identify those families in their neighborhood who are beginning to experience similar trials that are likely to lead to eventual shelter entry. With such peers on the front lines to identify and properly direct those families most in need, a truly localized prevention program will begin to take shape.

Tier III: CRRC Program Planning

Developing the Tier III CRRC program model

The following sections provide the program-level detail concerning the proposed structuring of Tier III residences, including the Advancing Employment Program, Furthering Education Program, Safety First Residence, Child Wellness Program, and Health and Recovery Program. The sections discuss the existing needs addressed by each program, the particular interventions employed to address those needs, and the anticipated outcomes for participating families.

Endnotes

1 Nancy Smith, Zaire Dinzey Flores, Jeffrey Lin, and John Markovic, Understanding Family Homelessness in New York City, Vera Institute of Justice, September 2005.

2 On a national level, the wide-scale promotion of rapid rehousing began in earnest in 2000; see National Alliance to End Homelessness, A Plan, Not a Dream: How to End Homelessness in Ten Years, 2000. Locally, New York City began its own version of rapid rehousing in 2005 with the Housing Stability Plus program, followed in 2007 by the Advantage program.

3 HUD’s funding shift away from support services in favor of the department’s more traditional funding of brick and mortar (shelter construction, renovation, and operation expenses) began in earnest in 2001 and has continued in this direction since; see U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Community Planning and Development Homeless Assistance Grants: 2011 Summary Statement and Initiatives, 2010.

4 Of all families who apply for emergency housing, roughly 40% receive no residential assistance beyond conditional placement; see New York City Department of Homeless Services, Critical Activities Report, FY10. Of those families who are found eligible for emergency housing, almost 10% receive assistance for less than one month; New York State Office of Temporary Disability Assistance, unpublished data released to ICPH, 2008.

5 Recent data regarding Advantage suggest that roughly 20% of families eligible for emergency housing in recent years were successfully assisted through the intermediate-level intervention of a short-term rent subsidy. According to the Department of Homeless Services’ Critical Activities Report, 28% of families eligible for emergency housing in FY10 exited shelter through a short-term rent subsidy. Data obtained by the Coalition for the Homeless show that 25% of those who exited in prior years through the Advantage short-term subsidy subsequently returned to emergency housing once the subsidy ended; see Patrick Markee and Giselle Routhier, “The Revolving Door Spins Faster: New Evidence that the Flawed ‘Advantage’ Program Forces Many Formerly-Homeless Families Back into Homelessness,” Coalition for the Homeless, February 2011. Taken together, this information shows that short-term rent subsidies, though not a suitable intervention for all, could quite possibly be a sufficient intervention for 20% of families eligible for emergency housing assistance.

6 Vera Institute of Justice, Understanding Family Homelessness, 2005. In “Testing a Typology of Family Homelessness,” Dennis Culhane makes the argument that families with longer shelter stays evidence fewer service needs. Though Culhane wants to use this information to argue for shorter shelter stays, a closer look at the report’s data shows that the longer shelter stays might actually protect against higher-level service needs. Even more, the study makes the direct argument for service-rich extended shelter stays for those families he identifies as most in need of support services, families he identifies as “episodically homeless.” See Dennis Culhane, Stephen Metraux, Jung Min Park, Maryanne Schretzman, and Jesse Valente, “Testing a Typology of Family Homelessness Based on Patterns of Public Shelter Utilization in Four U.S. Jurisdictions: Implications for Policy and Program Planning,” School of Social Policy and Practice Departmental Papers, 2007.

7 Department of Homeless Services, Critical Activities Report, FY10.

8 Ibid.

9 Under this model, the employment program offered at shelter sites would satisfy work requirements for those in shelter who are receiving cash assistance from TANF or the state’s Safety Net Assistance program.

10 Vera Institute of Justice, Understanding Family Homelessness, 2005.

xxx

CHAPTER 2—Tier III:

Advancing Employment, Developing Marketable Skills through Work Experience

It is estimated that almost 70% of homeless families are unemployed when applying for emergency housing assistance.1 Over 20% of homeless families report no work history in the five years prior to receiving emergency housing assistance.2 Even the employed families who exited shelter in 2010 were working at, on average, $9.50 per hour for 32 hours per week, leaving them with little more than $1,200 per month.3 With fair-market rent for a two-bedroom apartment in New York City over $1,400, self-sufficiency is often out of reach for the city’s homeless families.4

70% of homeless families are unemployed at shelter entry

xxx

The Disconnect between Work-based Housing Supports and the Actual Work Readiness ofHomeless Families

For homeless families with limited or no work histories, assistance obtaining and increasing employment are basic preliminary steps to housing stability. Yet the recent rent subsidies instituted in the city over the last several years, including Housing Stability Plus in 2005, Advantage NY in 2007, and Advantage in 2010, failed to properly incentivize stable employment. Housing Stability Plus, a five-year subsidy designed to incrementally step down from the full rent amount in the first year to 20% of the rent amount in the fifth year, required families to maintain an active public assistance case. Such a mandate was a practical impossibility, with families approaching the fifth year of the subsidy expected to pay an amount toward rent that would have approached the maximum income permissible under public assistance regulations. In other words, the rent expectation in the later years of the program would have far exceeded 50% of household income, a financial imbalance that would have spelled disaster for many families. Beyond this elementary program design flaw, Housing Stability Plus did little to encourage families to advance in their employment. Rather, incentives were designed to maintain an active public assistance case.

21% of homeless families held no work in the five years prior to shelter entry

xxx

Dead-End Jobs and Dead-End Incentives

The end of Housing Stability Plus and the advent of Advantage NY in 2007 pushed the “snag-a-job” approach to employment among homeless service providers. With the promise of 24 months of rent assistance for families documenting at least 20 hours of work per week, Advantage incentivized this rushed approach to employment. Starting in 2010, the City further pushed families in this direction by penalizing providers financially for families who resided in shelter beyond six months. Responding to these incentives, shelter-based employment services have taken a very simplistic form: rushing families into jobs without much regard to fit, quality and long-term sustainability. Under these constraints, only the few homeless families who already had some work experience witnessed even fleeting success. The limitations of this approach were evident in the fact that almost 50% of those families in shelter in a given year were never even eligible for Advantage. Of those who were eligible, less than half were able to maintain housing stability on their own once the subsidy ended.5

Average monthly earnings of a working homeless family $1,200

Work Readiness vs. Work Rhetoric

Though touted by some academics and advocates as a kind of panacea for the steadily growing problem of family homelessness, rapid rehousing rent subsidies like Advantage, with their documented shortcomings, proved to be a ready target for the state budget ax. With state dollars pulled from the rent subsidy programs in the 2012 budget, federal funds were lost, too, and the City decided to end the program entirely. Following Advantage, the rhetorical focus for DHS quickly turned to the perennial “work first” theme, yet now absent the work support of rent subsidies. The City’s current approach is largely the same as it was under Housing Stability Plus and Advantage, save for rent assistance. The only answer for families now is to be funneled into the Human Resource Administration’s (HRA) welfare-to-work programs, with the expectation that they reemerge in under six months, self-sufficient and ready to exit shelter. Recession-era unemployment rates and rampant underemployment seem not to discourage the City from pursuing this current strategy. Add to the challenges of a stagnant labor market the well-known inefficiencies, incompatibilities, and ineffectiveness of the HRA work programs, and the outlook for shelter exits is grim.

The lingering question, then, for emergency housing providers is how to best assist those families who present with real barriers to employment that exceed the scope of mainstream services. The solution, as we will see, might be closer at hand than suspected. Largely built upon existing infrastructure, personnel, and funding streams, the following proposal details an employment-readiness program targeting the specific needs of homeless families and suitable for adoption at the provider level.

In New York City, fair-market rent for a twobedroom apartment $1,400

xxx

Tier III Advancing Employment Program

The Tier III Advancing Employment Program will offer a clear path to sustainable employment through real work experiences that afford opportunities for on-site skill development, employee mentoring, and a stable context for employment search activities. Heads of household will build their work histories and develop essential skills through direct employment in residential services. Existing employment opportunities within the current shelter system, including child care, after-school support, kitchen operations, clerical work, custodial services, and security operations, offer a unique opportunity for never-employed families to become working families.

This hands-on approach to job readiness will be enhanced through individualized coaching sessions with on-the-job mentors. The real on-site work experiences will provide a relevant context through which mentors will engage participants in individual and group dialogue about how to improve employment potential, increase job stability, and strengthen career development. Participants will be guided through the process of developing marketable workplace skills, including industry-specific training as well as more general skills such as punctuality, follow-through, time management, dependability, and effective communication.

Advancing employment basics:

—Work experience

—Mentoring

—Job search

Participants will simultaneously develop the skills necessary to secure employment. Helping to improve the quality of cover letters and resumes and the efficiency of application submission, instruction in productivity software and online job search tools will help broaden the scope of employment opportunities available to participants. And rehearsal of interview scenarios will help bolster the confidence of participants as job prospects begin to materialize.

This multi-pronged approach to employment training of the Advancing Employment Program model addresses the major obstacles to work not only through direct intervention in the job search process but also, more foundationally, by helping people develop real work histories upon which a truly meaningful job search might be conducted. Simultaneously, the purposeful mentoring will help entry-level workers become sought-after employees.

Eligible families:

—Limited or no work experience

—High school diploma or GE D

—Motivated to develop new skills

—Amenable to intense on-the-job training

xxx

Target population

The Tier III Advancing Employment Program will function as a voluntary program into which families will have the option of enrolling. The program will target those heads of household who have attained at least a GED or high school diploma but who have very limited or no work experience. (A secondary track detailed in the following proposal, “Furthering Education,” will combine education and employment services for those unemployed heads of household lacking a GED or high school diploma.) Families eligible for the Advancing Employment Program will demonstrate a desire to develop marketable job skills. They will have an interest in furthering their knowledge of effective techniques for locating and securing stable employment. To offset their limited on-the-job experience, they will have direct guidance from a mentor who will teach them how to effectively navigate, and succeed in, a new work environment. Capitalizing on the expressed motivation of families in need, the program will seize the opportunity to help families achieve their greatest potential.

Program Components

When considering the effect of a limited work history on employability, certain barriers emerge as having a particularly detrimental effect on future job prospects. The Advancing Employment Program addresses these leading barriers by offering real work experience, development of industry-specific job skills and general workplace skills, competency in job search tactics, proficiency in interviewing techniques, and strategies for job retention.

Program Components:

Work experience—On-site paid employment helps to build a real work history

Job skills—Training in industry-specific job skills helps expand future employment opportunities

Workplace skills—Ability to anticipate employer expectations helps to increase value as an employee

Job search tactics—Gaining new writing and computer skills helps to broaden the job search

Interviewing techniques—Comfort with the hiring process helps improve chances of landing the right job

Job retention strategies—Knowing how to navigate a new work environment helps to advance from probationary employment to stable employment

xxx

Work experience

Often, the primary roadblock to employment is a lack of employment itself. Individuals with limited or no prior work experience find themselves with no foundation upon which to frame an application for employment. Consequently, resumes and job applications lack the substantive histories necessary to influence hiring decisions. Through the Advancing Employment Program, participants will gain real work experience through employment in positions regularly occurring in Tier III CRRC settings, including child care, after-school support, kitchen operations, clerical work, custodial services, and security detail.

Job skills

A deficit of marketable job skills particular to an industry or transferable across sectors limits available work opportunities. At the Advancing Employment CRRCs, co-workers on the job serve as mentors to participant trainees as they learn the skills necessary to succeed in their particular area of focus.

Workplace skills

Lack of familiarity with workplace expectations regarding attendance, dress, behavior, and communication can lead to job loss for those with minimal work histories. The mentor-trainee relationship central to the program serves as a safe space for participants to learn the ins and outs of expected behavior and communication in work settings, with early learning prioritized through modeling and corrective action.

Job search tactics

Minimal engagement with productivity software and online application tools, coupled with inexperience structuring resumes and cover letters, reduces the pool of jobs available to applicants. Individual and group sessions with Advancing Employment job coaches introduce participants to word processing applications and online tools for employment search, with hands-on instruction preparing resumes and crafting cover letters.

Interviewing techniques

Having few or no previous opportunities to interview for jobs makes applicants uncomfortable with the process, hampering their ability to effectively engage potential employers. Group role modeling of potential interview scenarios allows participants nearing the end of the program to hone new communication skills, establish a greater degree of ease with the interview process, and become adept at identifying possible pitfalls when meeting with potential employers.

Job retention strategies

Inexperience navigating workplace dynamics—including employer expectations, supervisor-trainee relationships, and interactions with co-workers—can impede career development and lead to job loss. Through the aftercare support services of job coaches who have worked with the participants throughout the process, job counseling is available at one of the most crucial points, the beginning of a new job, thereby promoting future success. As such, caseloads of job coaches are tailored to allow adequate time for the provision of aftercare support to participants once they secure alternate employment and relocate from the program residence.

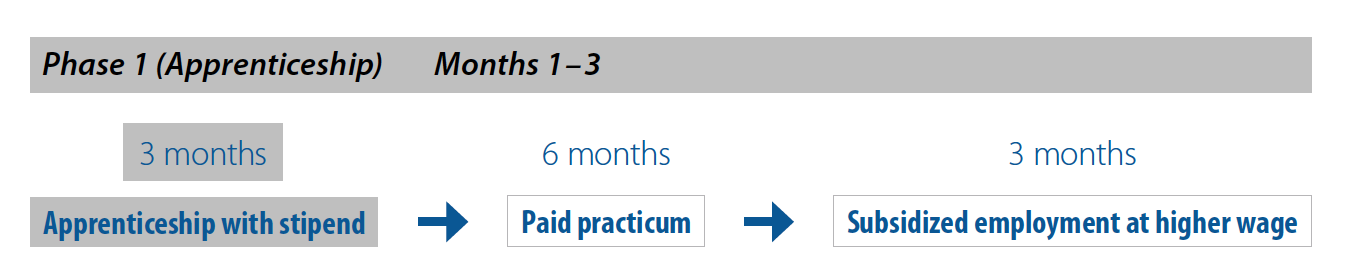

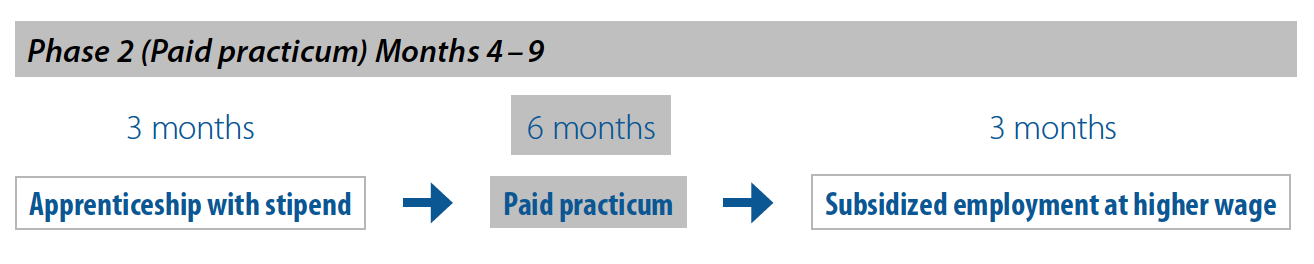

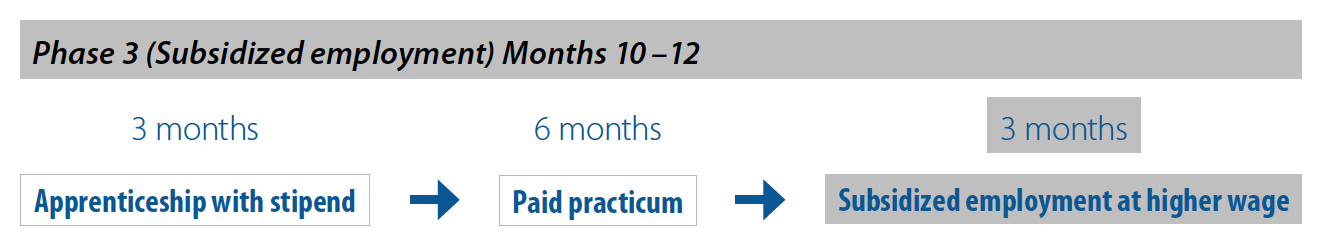

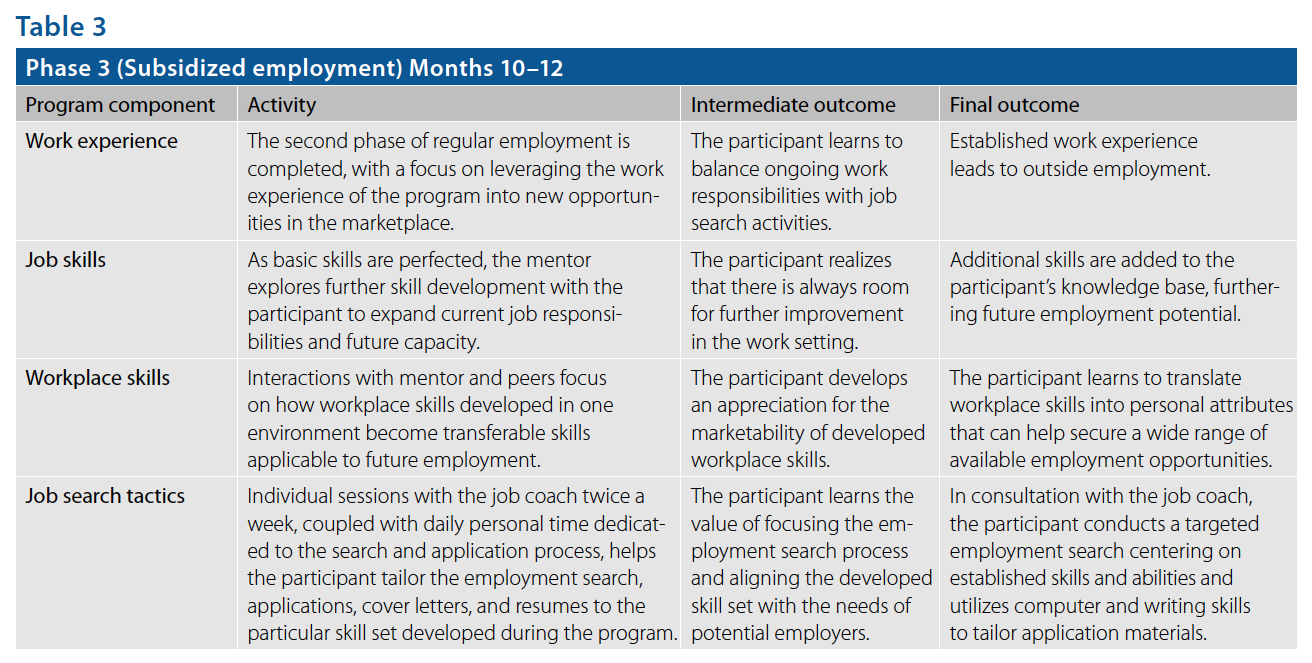

Service Progression

Progression through the program happens over the course of three phases, the first and third phases lasting three months each and the second phase lasting six months. Each phase seeks to address multiple program components, with cumulative learning happening in each of the core areas over the course of the three phases.

Mentors in the six areas of occupational training meet with the participants during the first week of residency to provide an overview of work expectations. Job coaches help the participants make informed decisions concerning the specific training to pursue. The participants learn to evaluate available work opportunities through the lens of personal interests and abilities. By the end of the first week, the participants each select an area of job training to pursue in the program.

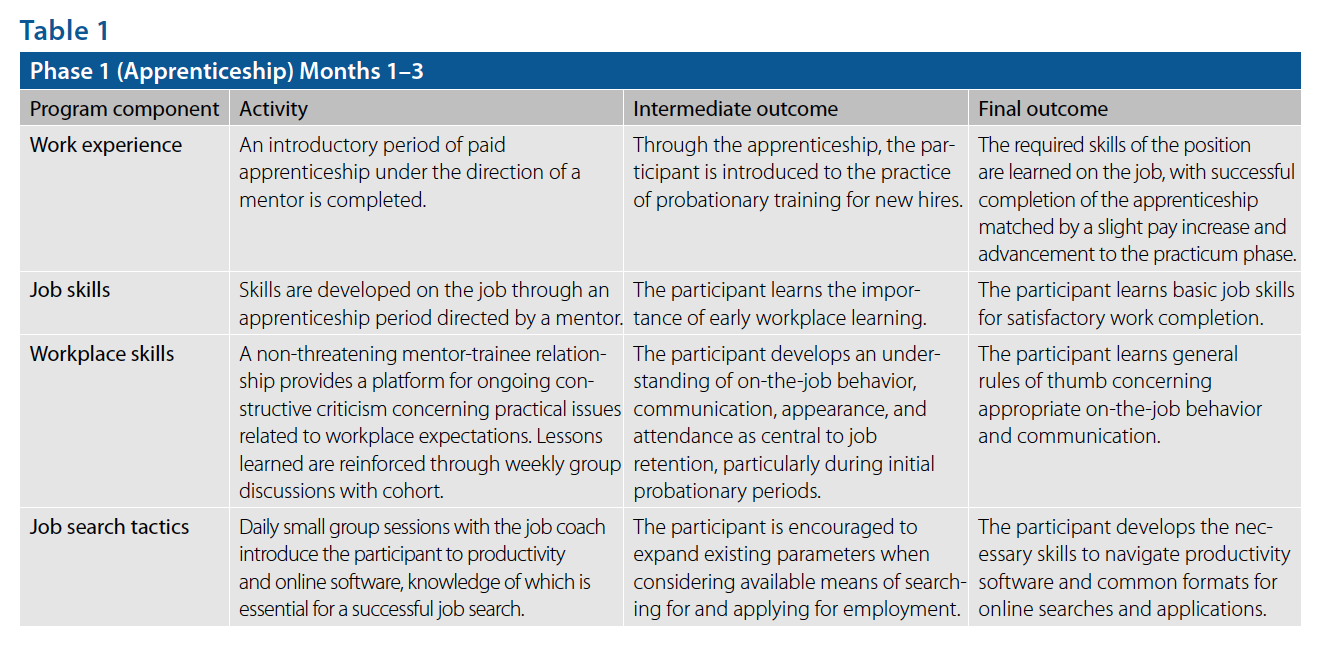

During the first three months, an introductory period of paid apprenticeship under the direction of a mentor is completed. Through the apprenticeship, the participant is introduced to the practice of probationary training for new hires. The required skills of the position are learned on the job, with successful completion of the apprenticeship matched by a slight pay increase and advancement to probationary employment.

During this time, skills are developed on the job under the direction of an assigned mentor. The participant learns the importance of early workplace learning and gains proficiency in basic job skills necessary for satisfactory work completion.

A non-threatening mentor-trainee relationship during the first three months provides a platform for ongoing constructive criticism concerning practical issues related to workplace expectations. Lessons learned are reinforced through weekly group discussions facilitated by the mentors. Participants develop an understanding of on-the-job behavior, communication, appearance, and attendance as central to job retention, particularly during initial probationary periods. This growing acceptance concerning the importance of these factors translates to adoption of behavior and communication styles that prove increasingly marketable to potential employers.

In terms of job-search skill development, daily small group sessions with the job coach during the first three months introduce the participant to productivity and online software, knowledge of which is essential for a successful job search. Participants are encouraged to expand existing parameters when considering available means of searching and applying for employment. At the same time, they develop the necessary skills to navigate productivity software and common formats for online searches and applications.

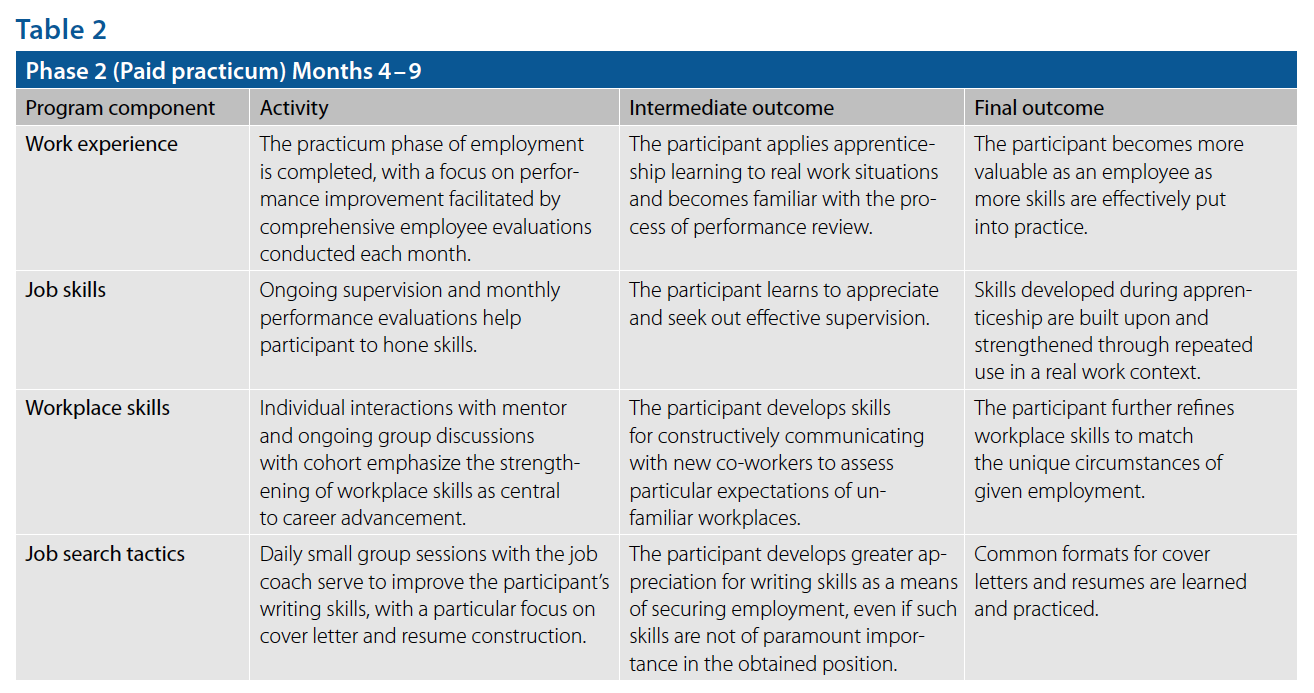

A phase of probationary employment is completed between the fourth and ninth months, with a focus on performance improvement facilitated by comprehensive employee evaluations conducted each month. During this time, participants apply apprenticeship learning to real work situations and become familiar with the process of performance review. Through the process, participants become more valuable employees as more skills are effectively put into practice.

Ongoing supervision and monthly performance evaluations between the fourth and ninth months help participants hone their skills. Skills developed during the apprenticeship are built upon and strengthened through repeated use in a real-work context while participants learn to appreciate and seek out effective supervision.

Between the fourth and ninth months, individual interactions with the mentor and ongoing group discussions with their peers in the program emphasize the strengthening of workplace skills as central to career advancement. Participants develop skills for constructively communicating with new co-workers to assess particular expectations of unfamiliar workplaces. Through these exercises, they learn to further refine their workplace skills to match the unique circumstances of given employment.

Daily small group sessions with the job coach during the second phase serve to improve the participants’ writing skills, with a particular focus on cover letter and resume composition. Participants develop greater appreciation for writing skills as a means of securing employment, even if such skills are not of paramount importance in the obtained position. At the same time, common formats for cover letters and resumes are learned and practiced.

After completing their probationary employment period, participants enter a phase of regular employment, which is completed between the tenth and 12th months, with a particular focus on leveraging the work experience of the program into new opportunities in the marketplace. The participants learn to balance ongoing work responsibilities with job search activities, with the established work experience eventually leading to outside employment.

As basic skills are perfected, the mentor explores further skill development during this phase, with the participants expanding current job responsibilities in ways that will augment future performance. Recognizing there is always room for further improvement in the work setting, participants expand their existing knowledge base, with additional skills helping to further future employment potential.

Interactions with mentors and peers focus on how workplace skills developed in one environment become transferable skills applicable to future employment.

Participants develop an appreciation for the marketability of developed workplace skills and learn to translate workplace skills into personal attributes that can help secure a wide range of available employment opportunities.

Individual sessions with the job coach twice a week, coupled with daily personal time dedicated to the search and application process, help the participants tailor the employment search, applications, cover letters, and resumes to the particular skill set developed during the program. Participants learn the value of focusing the employment search process and aligning the developed skill set with the needs of potential employers. In consultation with the job coach, participants conduct a targeted employment search centering on established skills and abilities and utilize computer and writing skills to tailor application materials.

During this final phase, interviewing skills are practiced and refined in weekly group sessions, with members taking turns playing the part of applicant and employer and providing one another with constructive criticism.

Transition to community

The goal for all families in the Advancing Employment Program is to obtain outside employment, and then move on to permanent housing. Housing search assistance will be provided and many of the skills learned during the program will also assist families in this regard. For families whose income is not sufficient to obtain and maintain market-rate housing, they will be prioritized for public housing or a Section 8 housing voucher, resources that must be targeted to those most in need.

Aftercare services will be part of every Tier III CRRC Program. Families transitioning from a CRRC will still be able to receive in-office services as needed from the same providers they have grown to trust during their time in residence. The support system does not vanish when the parent obtains a job and signs a lease. Rather, key providers and services remain close at hand as a lifeline should future crises emerge. Even more, ongoing everyday support around child care, after-school supervision, and other family goals are readily accessible to families as they continue on their paths to growing stability.

Endnotes

1 Nancy Smith, Zaire Dinzey Flores, Jeffrey Lin, and John Markovic, Understanding Family Homelessness in New York City, Vera Institute of Justice, September 2005.

2 Ibid.

3 Giselle Routhier, “Revolving Door: How the Bloomberg Administration is Putting Thousands of Formerly-Homeless Families at Risk of Returning to Homelessness,” Coalition for the Homeless, July 2010.

4 National Low Income Housing Coalition, “Out of Reach 2011,”www.nlihc.org.

5 According to the Department of Homeless Services’ Critical Activities Report, 28% of families eligible for emergency housing in FY10 exited shelter through a short-term rent subsidy. Data obtained by the Coalition for the Homeless show that 25% of those who exited in prior years through the Advantage short-term subsidy subsequently returned to emergency housing once the subsidy ended, 6% were made eligible for another subsidy after entering into eviction proceedings, and 16% transitioned to the long-term rent subsidy of Section 8; see Patrick Markee and Giselle Routhier, “The Revolving Door Spins Faster: New Evidence that the Flawed ‘Advantage’ Program Forces Many Formerly-Homeless Families Back into Homelessness,” Coalition for the Homeless, February 2011.

xxx

CHAPTER 3—Tier III:

Furthering Education, Continuing Studies to Achieve Success

Over half of all homeless heads of household do not have a high school diploma or general equivalency degree (GED).1 This lack of educational attainment among homeless families translates to chronic unemployment, lower wages, and fewer hours worked each week, a sure recipe for ongoing housing instability. New Yorkers who hold a high school diploma or GED earn 65% more over their lifetime than New Yorkers who lack this basic level of education.2 Even more, women in New York with a high school diploma or GED earn 94% more than other female New Yorkers with less education.3 Individuals without a high school diploma or GED are known to require more social services over their lifetime than those who hold these credentials, with the less-educated group consuming more in services than they return to the City coffers through taxes.4 Despite the obvious advantages of an educated citizenry, fewer than 2% of New Yorkers lacking a GED even take the test each year.5

Failure to incentivize education

Deadlines for exiting emergency housing serve as a strong disincentive for furthering education. Because of strict City policies that push families to find a job quickly, many in need bypass educational goals in their rush to find employment. The result is a continuing cycle of unstable, low-wage work, with little hope for advancement given educational deficiencies.

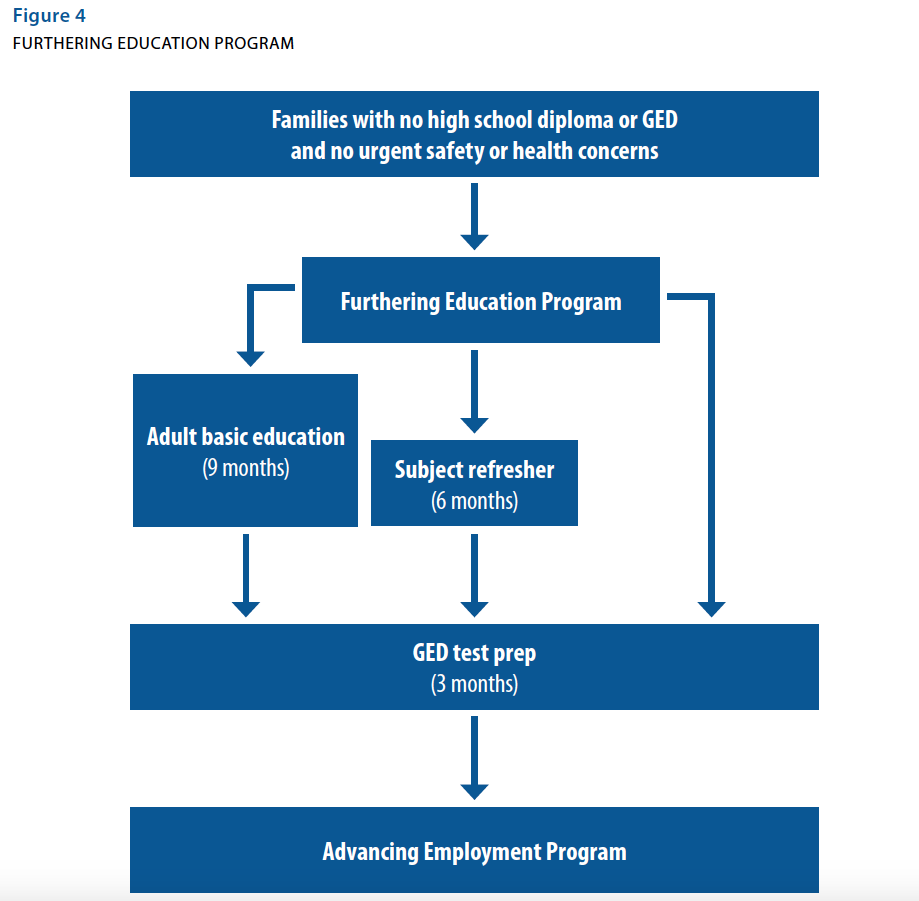

Tier III Furthering Education Program

A Tier III Furthering Education Program will help correct the current incentive structure so that families will be encouraged and supported to pursue educational advancement. Heads of household lacking a high school diploma or GED will prioritize their education first. Upon obtaining their GEDs, these parents will transition to job readiness and employment search services. Though this model necessarily means a longer length of stay in residence, it will also mean greater success when transitioning to independence, a program strength that will translate to fewer families reapplying for emergency housing assistance.

56% of homeless heads of household never graduated high school

xxx

Target Population

Tier III Furthering Education Programs will target families whose primary barrier to employment and housing stability is the head of household’s limited education. Though families with higher-level service needs, such as mental health issues or child welfare involvement, might also need assistance with GED preparation, such families will not be targeted for Furthering Education Programs. Rather, these families will be targeted for residential placement according to their primary service need, with necessary educational services offered as a supplement to those services designed to address the family’s primary barrier to stability. In this way, the Furthering Education Programs will be singularly focused on GED preparation, limiting the number of obstacles to positive program outcomes for both staff and participants.

Eligible families

—No high school diploma or GED

—Motivated to obtain GED

—Understand importance of prioritizing education

xxx

Program Components

The Tier III Furthering Education Program will work exclusively to prepare participants to pass the GED test. Heads of household will be the primary focus of this intervention, although dependent children who have dropped out of school will also be eligible for course enrollment. Preparation for the GED exam will be tailored to the skill level of participants, with similarly skilled individuals grouped together to facilitate timely progress.

Understanding that some participants will test higher at program entry than others and that certain individuals will be stronger in some subject areas and weaker in others, participants will be assigned to one of three tracks upon program entry. Individuals with significant educational deficiencies in multiple subject areas will follow the adult basic education track, through which they will receive extensive training in all subject areas (reading, writing, social studies, science, and math). Participants struggling with just one or two subject areas will enter the subject-refresher track, where they will receive additional guidance and instruction in just those subjects they find particularly challenging. A third group assessed with sufficient abilities in all subject areas will enter the test-preparation track, where they will be trained in test-taking techniques, with practice exams as a central focus of the training. The test-preparation track will also serve as the final program stage for individuals completing either the adult basic education track or the subject refresher track.

Understanding the many reasons people do not finish high school, including differences in learning style and ability, teachers in Furthering Education Programs will be trained to work closely with participants to identify and overcome barriers to education. A manageable student-to-teacher ratio and full workday schedule will provide teachers with the flexibility to employ teaching strategies according to the identified learning styles of students, thus maximizing the beneficial outcomes of the program.

Service Progression

Central to the enrollment process in Furthering Education Programs will be an assessment of educational abilities. The Test of Adult Basic Education, or similar assessment tool, would help determine the appropriate education track for each incoming participant. Those with significant deficiencies in one or a number of subject areas will be further assessed for learning styles and abilities. Participants will be assigned to one of three education tracks.

Those entering the adult basic education track will participate in a daily schedule similar to a traditional school setting, with students receiving instruction in each of the five subject areas five days a week. Given the greater educational needs of these students, completion of this phase of the program will take at least nine months.

Students entering the subject-refresher track will also be scheduled to receive instruction a minimum of 35 hours per week, but this training will focus on only one or two subject areas, allowing students to complete this phase of the program in three to six months, depending on the number of subjects pursued.

More advanced students will enter directly into the test-preparation track while others will enter this phase only after completing either the adult basic education track or the subject-refresher track. For all, this final education phase of the program will be completed in two to three months, depending on the student’s capacity to achieve a passing grade on the GED practice tests. Proven success on the practice tests will lead to scheduling of the actual test. Once students obtain their GED, the student resident will be reassessed for eligibility in a Tier III Advancing Employment Program.

Endnotes

1 Nancy Smith, Zaire Dinzey Flores, Jeffrey Lin, and John Markovic, Understanding Family Homelessness in New York City, Vera Institute of Justice, September 2005.

2 Lazar Treschan and David Jason Fischer, From Basic Skills to Better Futures: Generating Economic Dividends for New York City, Community Service Society, September 2009.

3 Female adults in New York City (18 – 64 years old) who do not have a high school diploma or GED have lifetime earnings of $389,156 compared to $753, 988 for those with it; Paul Harrington, Labor Market and Fiscal Impacts of Educational Attainment in New York City, “Multiple Pathways to Success: Graduation and Beyond,” New York City Dropout Summit, Brooklyn, N.Y., March 6, 2009.

4 Net fiscal cost for less than high school or equivalent = $-134,037. Net fiscal benefit for HSD or GED = $192,715. Costs are derived from the cost of institutional expenditures (such as incarceration and shelter) and cash and in-kind transfers, while benefits are derived from tax payments; Paul Harrington, Labor Market and Fiscal Impacts of Educational Attainment in New York City, “Multiple Pathways to Success: Graduation and Beyond,” New York City Dropout Summit, Brooklyn, N.Y., March 6, 2009; Lazar Treschan and David Jason Fischer, From Basic Skills to Better Futures: Generating Economic Dividends for New York City, Community Service Society, September 2009.

5 Christine Quinn and Maria del Carmen Arroyo, “Citywide GED and Adult Education Campaign,” Release #084-2010, City Hall Office of Communications, New York, August 24, 2010.

xxx

CHAPTER 4—Tier III:

Safety First Residence, Support for Families Fleeing Violence

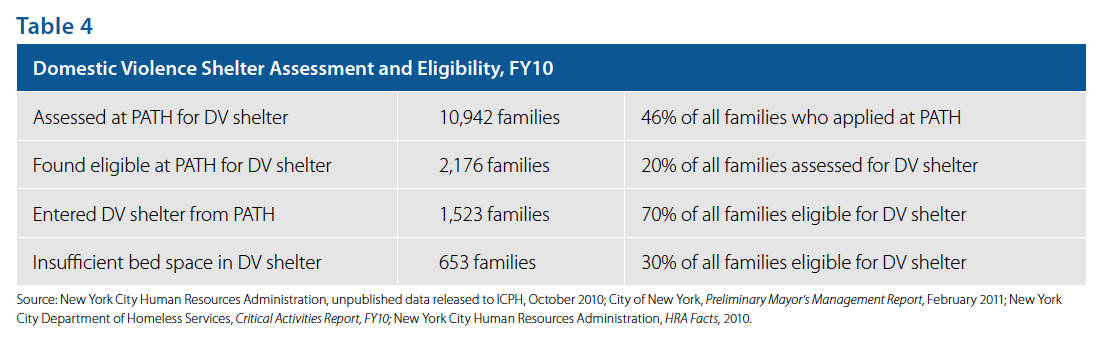

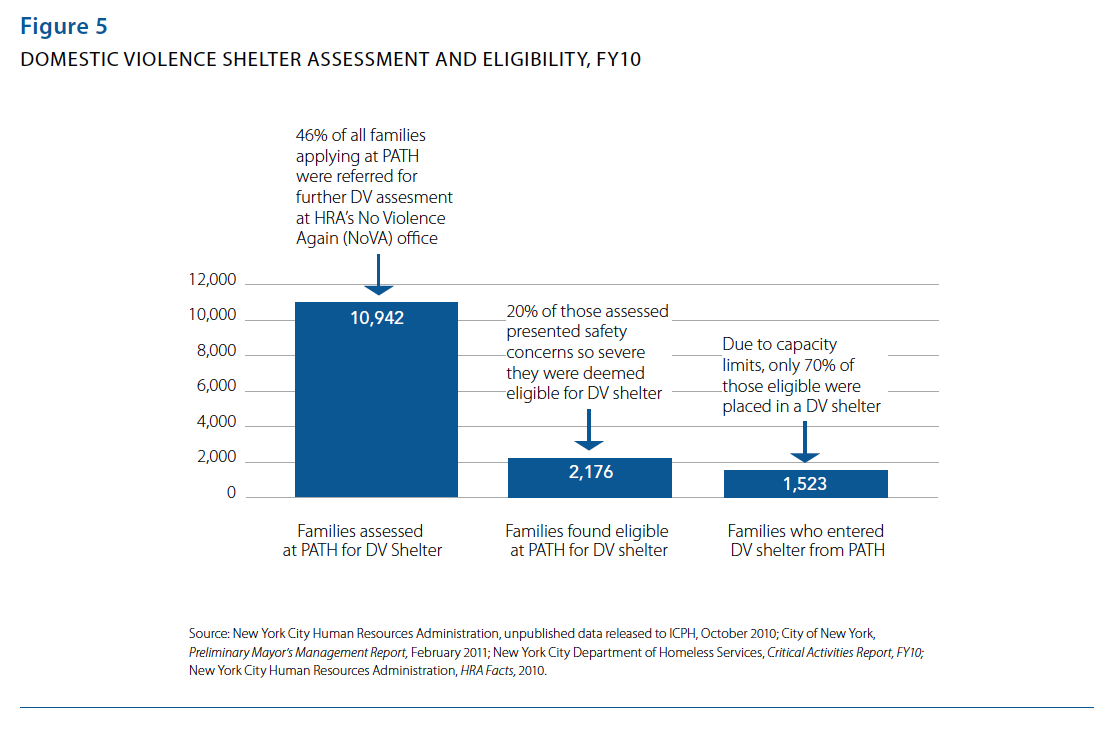

In Fiscal Year 2010, nearly half of all families applying for emergency housing assistance in New York City were referred for further domestic violence assessment based on reports of abuse presented at intake. Of those completing this further assessment, 20% were found eligible for placement in a domestic violence shelter. However, due to limited capacity, only 70% of applicant families were able to receive these critical domestic violence services. The rest of the 650 families fleeing domestic violence, all with verified safety concerns, were forced to make do with placement in the mainstream shelter system, a solution that compromised family safety and well-being.1

With only 2,200 domestic violence shelter beds in the city, the length of stay for such emergency assistance is capped at 135 days, with many victims either returning to their abuser or entering the mainstream shelter system upon reaching their time limit.2 The difficulty of breaking free from the cycle of abuse is complicated by the abuser’s manipulation of the victim’s emotions as well as real issues of financial dependence, worsened by low educational attainment and poor work histories among some victims.3 Even more, exposure to violence in the household jeopardizes the healthy development of children, contributing to potential academic and emotional setbacks requiring a trauma-informed approach to service delivery to correct.4 Given the nature of these obstacles, seemingly insurmountable to the victims of violence who face them, emergency services must be structured to provide time and resources adequate for the rebuilding of lives independent of abusers.

Tier III Safety First Residence

Tier III Safety First Residences will build on the proven practices of countless domestic violence service providers who have documented the best approaches to helping victims of violence leave their abusers. Coupling this wealth of practice wisdom with the education and employment support services necessary for families to become independent, Safety First Residences will afford victims of abuse the time and resources to regroup, heal, and move forward to a future free of violence.

Target Population

Existing assessment procedures integrated into the family shelter application process serve to identify those families most in need of targeted domestic violence services. Families so targeted are those with verifiable safety concerns such that the added protection of an undisclosed shelter location is necessary to guard against further family victimization. Tier III Safety First Residences will serve the needs of those families found eligible for domestic violence shelter who are unable to access such services due to capacity limits of the current system. Safety First Residences will also prioritize those families who enter domestic violence shelters but time out of the system before achieving independence; at the end of their limited stay in a domestic violence shelter, these families will transition to the additional support services of a Safety First Residence.

Program Components

Of greatest concern in the Safety First Residence will be protecting families against further abuse and violence. Ensuring that all those deemed eligible for domestic violence services receive them, Safety First Residences will help close the gap on unmet need. Operating in undisclosed locations, the residences will provide an additional shield against abusers who would be more likely to track victims at the publicly available addresses of the mainstream shelter system. This added layer of protection will help distance victims from the undue influence of abusers’ manipulation, threats, and violence, affording traumatized families a real opportunity to make lasting transitions to independence. With safety as the cornerstone, the residences will foster an environment where victims and their families will feel comfortable disclosing details of abusive relationships, leading to more productive counseling sessions and greater progress toward sustained independence. Counseling services will be offered to both parents and children, with play therapy addressing the identified emotional needs of younger children.