On the Map

Community Profile

February 2016

The June 2014 opening of the Boulevard Family Residence in the former Pan Am Hotel in Elmhurst, Queens put that community at the center of a debate on homelessness in New York City. Despite only having one shelter in the Community District with capacity for roughly 200 families, fears of homelessness and poverty being brought in from outside the community have grown. Family homelessness and poverty, however, have existed in Elmhurst/Corona long before the opening of any shelter.

Behind the headlines on shelter placement lies a more critical local issue. Higher-income residents are moving into parts of Elmhurst/Corona, rents are rising, and the housing stock affordable to extremely low-income residents is dropping. Residential and school overcrowding are high even for a densely populated city like New York, and child care capacity is inadequate. Are changing characteristics in a neighborhood divided in its experience of gentrification, poverty, and homelessness a signal of turmoil to come? The On the Map Community Profiles look at the factors at play in neighborhoods and not only what drives family homelessness, but also community and housing instability.

Key Findings

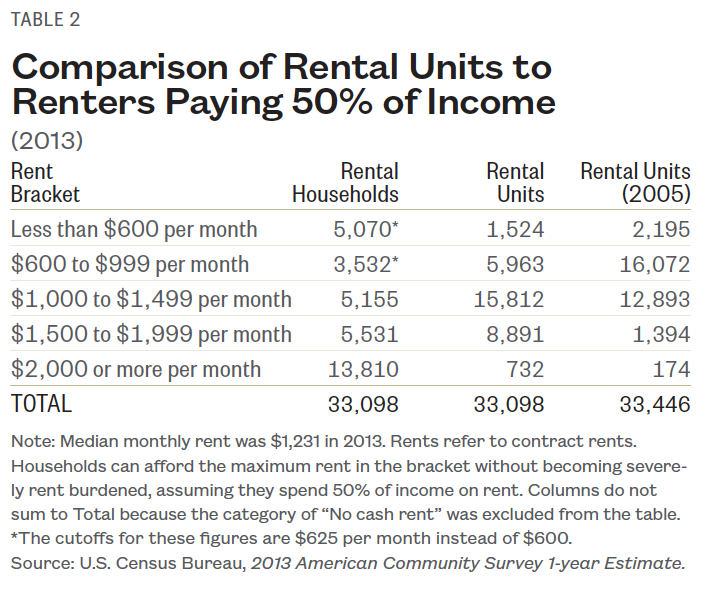

The need for low-rent apartments was four times higher than the number of apartments available at that rent level in 2013, with roughly 5,000 renters competing for just 1,500 units.

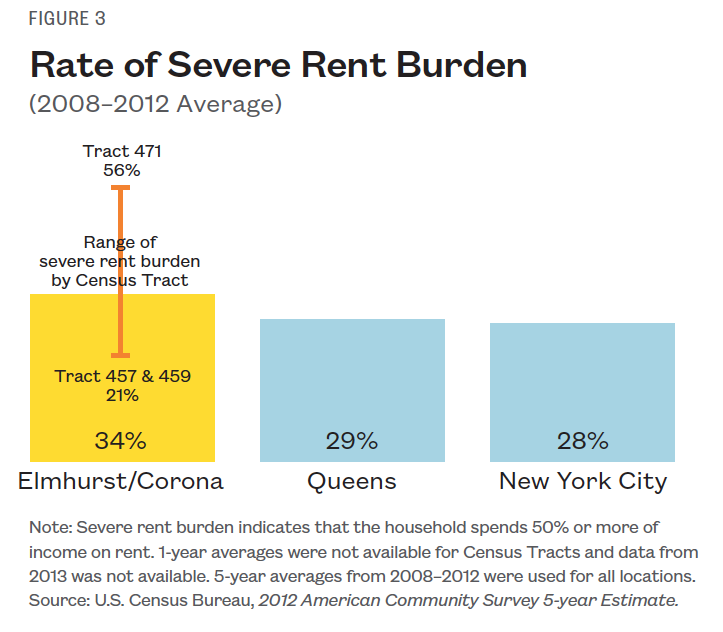

Over one-third of renters in Elmhurst/Corona spent less than a third of their income on rent in 2013, but in the area south of the Long Island Railroad (LIRR) and just east of Broadway in south Corona, 56% of residents pay more than half of their income on rent—double the City average of 28%.

Elmhurst/Corona is New York City’s second most overcrowded neighborhood and its third most overcrowded School District.

Homelessness in the community is hidden, found primarily in those living doubled and tripled up with others, rather than in shelters. For every homeless student in shelter there were 8 students living doubled up.

xxx

xxx

The Affordability Gap

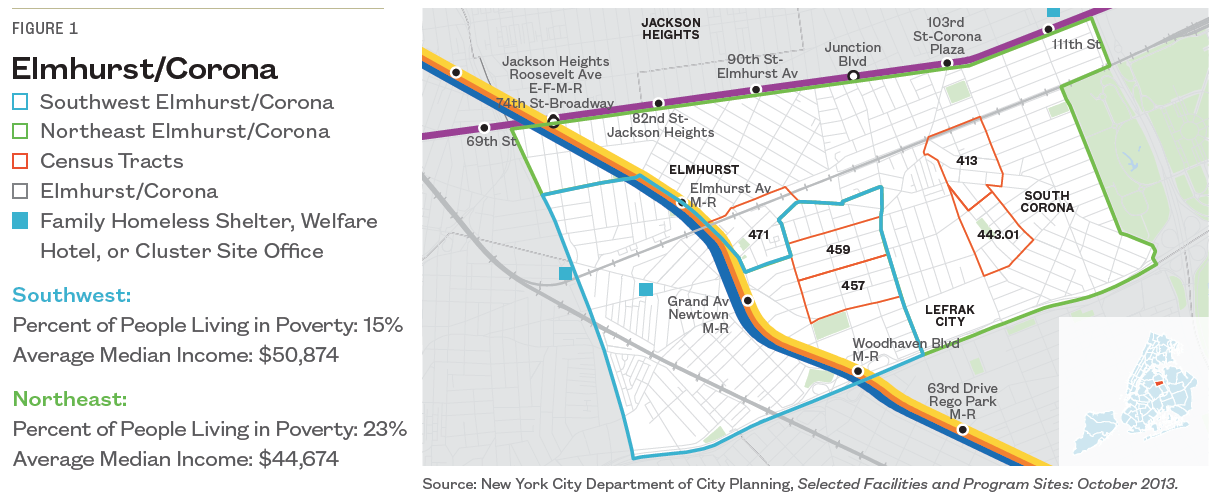

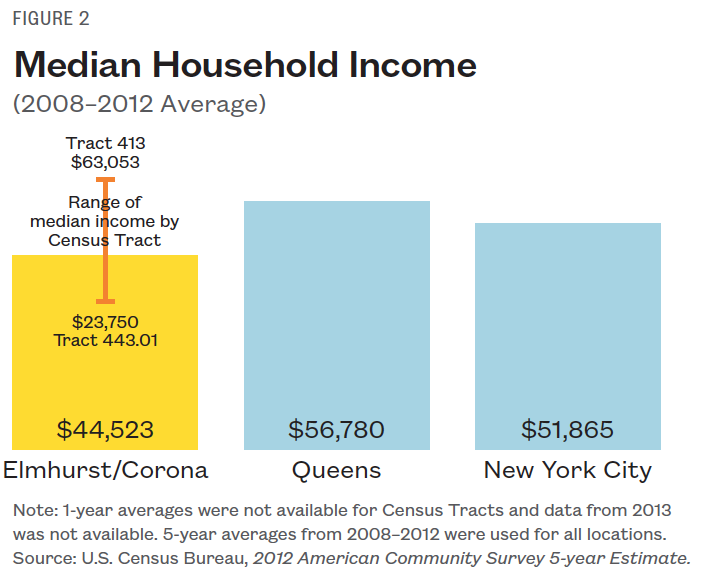

Despite remaining predominantly working-class, Elmhurst/Corona has experienced an influx of more affluent newcomers. Between 2005 and 2013, the number of households earning at least $100,000 more than doubled—from 8% to 17%—while the population in almost every other income bracket fell. Based on U.S. Census data, median income in Elmhurst/Corona appears to be lower than the citywide median, but as is shown in Figures 1 and 2, sharp differences exist between neighborhoods within the community.

Median household income ranged from $23,750 to $63,000 by Census Tract, with residents in the Census Tract bounded by the LIRR to the north and Broadway to the west (Tract 471) over twice as likely to live in poverty as the community as a whole—43% compared to 21% overall (Figures 1 and 2).

Housing in Elmhurst/Corona is increasingly likely to meet the needs of middle-income renters earning at least $25,000 rather than low-income residents. Of the 33,000 renters in 2013, over one-third paid less than 30% of their income in rent and, as shown in Table 2, the 10,686 residents seeking units at the higher $1,000– $2,000 level found a surplus of rental opportunities. For the 5,070 renters in the lowest income bracket, however, there was only one apartment for every three renters in need, or just 1,524 units.

Elmhurst/Corona’s affordability gap has been growing since at least 2005, when reliable data became available. This discrepancy in available units has made the neighborhood an affordable community for many middle- and high-income households and nearly unaffordable for many low-income households. The maximum rate of rent burden from 2008 to 2012 shown in Figure 3 was found in the northeast section, where as many as 56% of households were severely rent burdened in Census Tract 471 (mentioned above)—paying 50% or more of their household income on rent—double the City average of 28%. Two tracts in the southwest, 457 and 459 located between 50th Ave and 56th Ave, saw the lowest severe rent burden rate of the community: just 21% of residents paid half or more of their income on rent (see Figure 1 map).

xxx

xxx

xxx

xxx

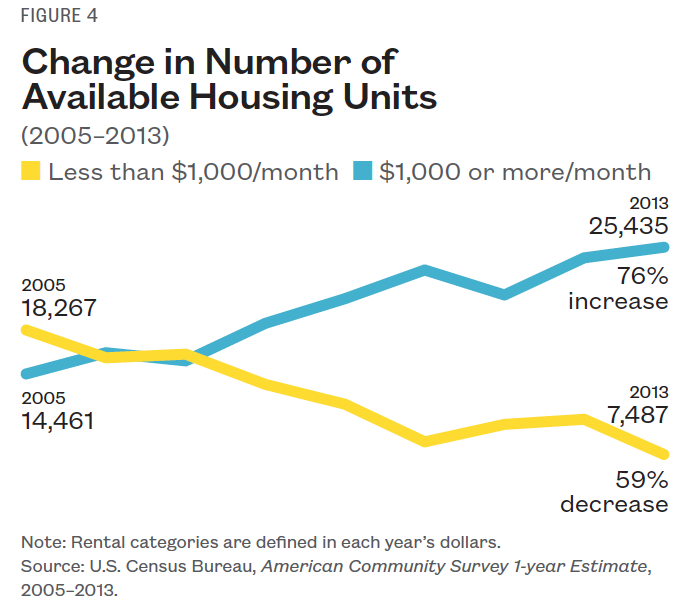

Availability of units renting for more than $2,000 has quadrupled in nine years (although they are still few in number), while low-income housing (units renting for under $600 monthly) shrank by 31%. As seen in Figure 4,4 the number of units renting for over $1,000 now far exceeds those renting for less than $1,000. The number of households that could afford only low-income housing also declined, a trend that reflects the shrinking housing availability in that price range.

Rippling Signs of Strain

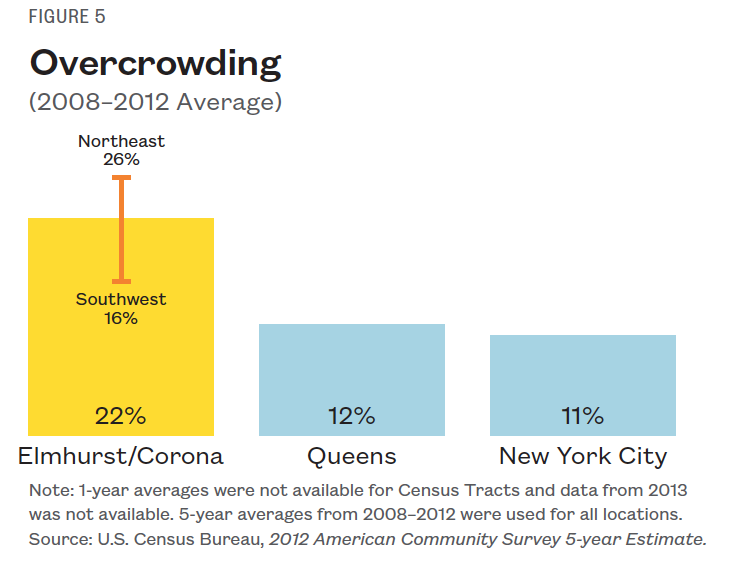

As rents climbed, so too did residential and school overcrowding. Between 2005 and 2013, the number of overcrowded renter-occupied units jumped from roughly 5,500 to over 9,000 units, making Elmhurst/ Corona the second most overcrowded of New York City’s 59 Community Districts with two times the rate of overcrowding seen in New York City as a whole (22% compared to 11%) (Figure 5). This burden was concentrated in the northeast section, the same area that had the highest rate of severe rent burden. There 26% of renters were overcrowded, four percentage points above the neighborhood’s average, and 10 percentage points higher than in the southeast section of Elmhurst/Corona.

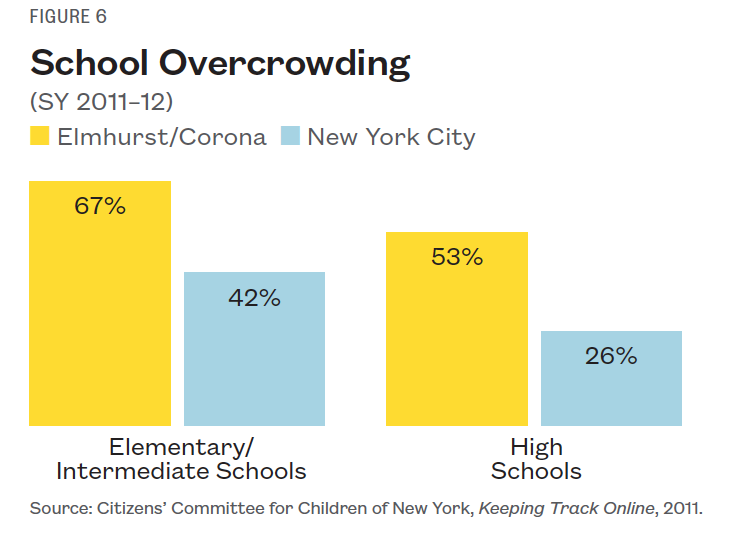

The strain of overcrowding extends beyond struggling households and into the neighborhood school system. In SY 2011–12, Elmhurst/Corona’s School District (District 24) was the third most overcrowded of New York City’s 32 School Districts. As seen in Figure 6, two-thirds of elementary/intermediate schools and 53% of high schools were overcrowded, compared to 42% and 26% citywide. Child care capacity is also inadequate. In 2010, the eastern half of the District had some of the highest unmet child care needs in New York City with an unmet demand for over 20,000 spaces in day care or afterschool care programs.5 In 2013, just 49% of 3- and 4-year olds in the neighborhood were enrolled in a pre-Kindergarten program compared to 60% citywide.

xxx

xxx

xxx

Homelessness in the Neighborhood

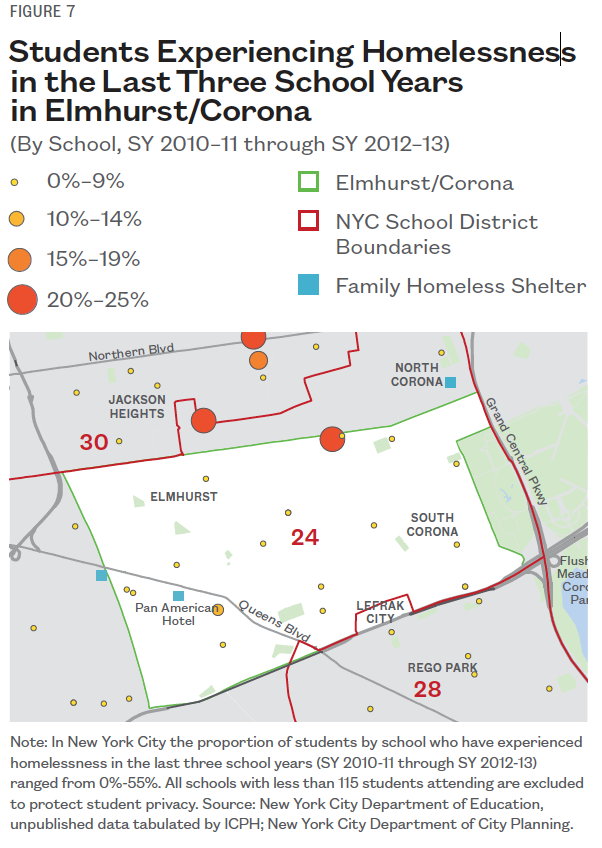

Family homelessness is growing in Elmhurst/Corona, though it is not readily visible. In SY 2012–13, there were 881 homeless students, and more than 1,200 children at local schools were homeless at some point from SY 2010–11 to SY 2012–13 (Figure 7). Despite this, homelessness is largely hidden since most homeless residents are living doubled up with family or friends rather than in shelters or on the street. Roughly 85% of homeless students were living doubled up in SY 2012–13, while only 11% lived in shelters and 4% lived in cars, abandoned buildings or other unfit locations. While the number of neighborhood families entering homeless shelters has remained low at between 12 and 56 each year since 2005, the number of homeless students has grown by 16% from SY 2010–11 to SY 2012–13, a trend reflective of growing neighborhood strain.

Bridging the Divide

This report began by noting community hostility to the opening of the 200-unit Boulevard Family Residence in Elmhurst/Corona, Queens, the first and only homeless family shelter in that district. That action also raised community fears that homelessness was being brought in from outside and the sheltered were being brought into their community. However, the data presented within this brief clearly suggest that the prevalence of family homelessness in the Elmhurst/Corona community is homegrown. Specifically, the correlation of increasing incomes with significant increases in rents, growing number of households paying more than 50% of their income on rent, the ongoing contraction of available low income housing, and the increased number of doubled up families indicated by the growing number of homeless students in the district, all signal a high risk for a potential surge of homeless families from within the community.

Without careful planning, community development and gentrification often pushes lower income residents out of desired and affordable neighborhoods. Such has been the case in Brooklyn over the past several years. Whether or not Elmhurst/Corona will be able to stem the tide remains to be seen. However, by understanding that a potential crisis is on the doorstep, this community has a unique opportunity to manage, and hopefully reduce, the instability that ultimately drives many families into homelessness.

1 Jackie Strawbridge, “Elmhurst United Protests Pan Am Conditions,” Queens Tribune, December 18, 2014. Bytes of the Big Apple, Selected Facilities and Program Sites, December 2014, www.nyc.gov accessed October 19, 2015. | Katie Honan, “Pan Am Hotel Quietly Reopens as Homeless Shelter,” DNA Info, June 12, 2014. New York City Department of Education, unpublished data tabulated by the Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness.

4 Rent refers to contract rent. Contract rent is the monthly rent agreed to or contracted for, regardless of any furnishings, utilities, fees, meals, or services that may be included. For vacant units, it is the monthly rent asked for the rental unit at the time of interview. Includes occupied housing units that were for rent, vacant housing units that were for rent, and vacant units rented but not occupied at the time of interview.

5 Office of Children and Family Services, 2013 Division of Child Care Services Data.