a policy brief from ICPH

December 2016

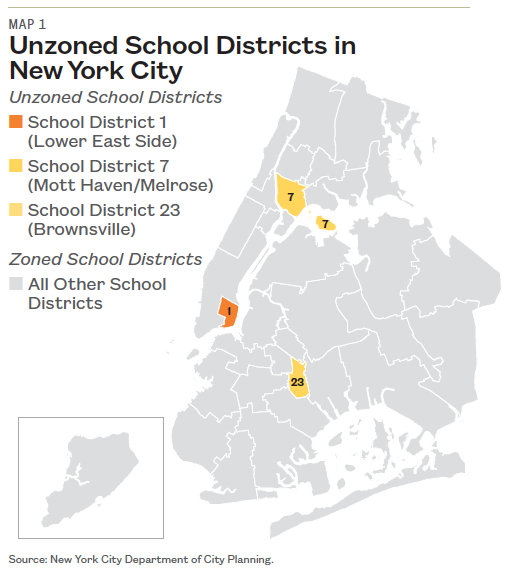

School choice plays a significant role in public education, whether determined by where you live (zoning) or other ways in which families select schools, such as vouchers or charter schools. In New York City, officials support families in having choices for their children, resulting not only in the rapid growth of charter schools, but also in the creation of three unzoned school districts.1 In these districts, elementary school enrollment is not based on a student’s address, but on parental choice and a lottery system when school applications exceed capacity. Importantly, all three unzoned districts serve communities where the number of homeless students exceeds the citywide average (Map 1), and District 1’s homeless student population is two times higher than the average.2 If school choice is another tool in the New York City Department of Education’s (DOE) belt to level the playing field and provide opportunities for disadvantaged students, what does it mean if the unzoned districts are in fact increasing segregation?

Unzoned School Districts in New York City (Map 1)

As a matter of policy, school choice is supposed to level the playing field between students of differing social and economic backgrounds. However, analyzing enrollment trends among homeless students in District 1, the unzoned school district that covers most of the Lower East Side of Manhattan, reveals that this district is the most segregated school district by housing status in the city. Understanding the dynamics in District 1 may yield insights that can help fine-tune policies that seek to improve the mechanisms and implementation of school choice so that students in need of additional supports—such as homeless students—do not suffer from unintended consequences. Choice should foster the redistribution of students in the name of equity and equality and empower parents, rather than segregating and isolating vulnerable students as in District 1.

Key Findings

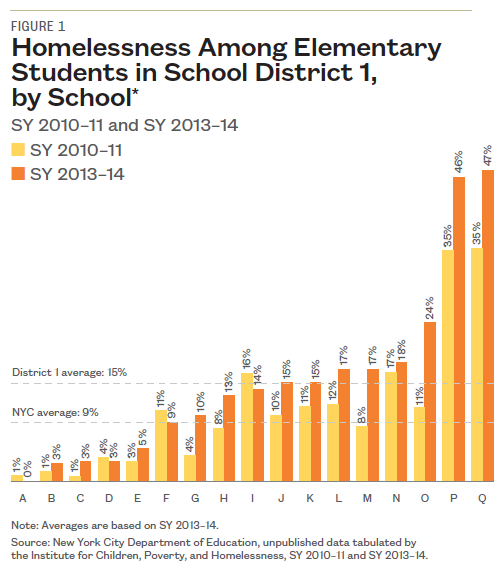

- Rates of homelessness among elementary students in School District 1 varied dramatically by school. While 15% of elementary students overall were homeless in SY 2013–14, homelessness in individual schools ranged from 0% in one school to 47% in another. In New York City on average 9% of elementary students were homeless in SY 2013–14.

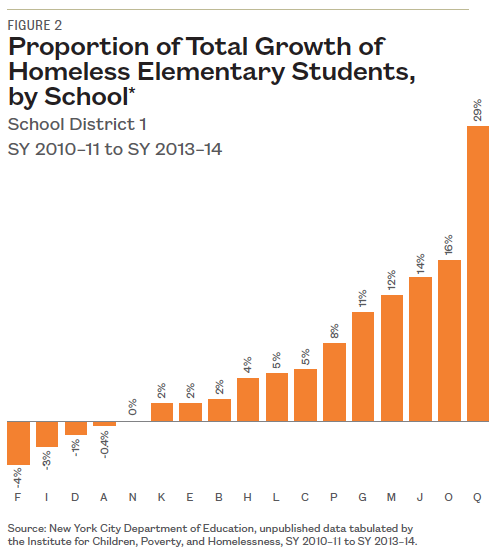

- Between SY 2010–11 and 2013–14, one school accounted for 29% of the total growth in the number of homeless students in District 1.

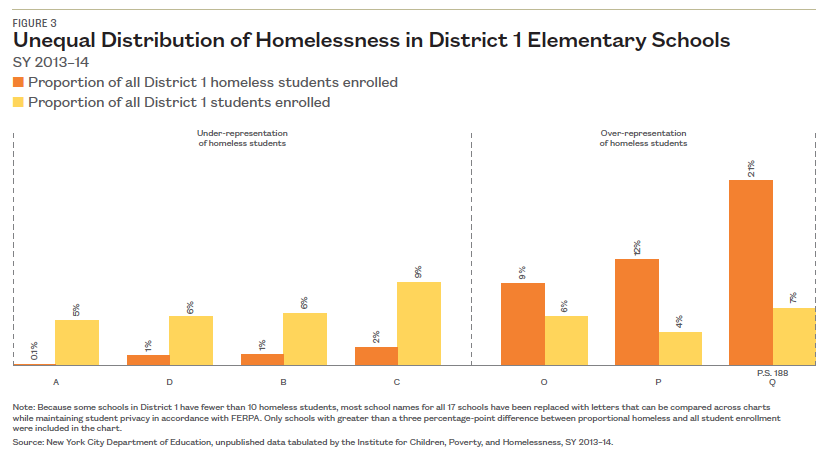

- District 1 was the most segregated school district in New York City by housing status, with over 20% of homeless elementary students attending just one school in the district.

The First Unzoned School District: District 1

New York City School District 1 is a small district with roughly 5,400 elementary school students encompassing the East Village and Lower East Side of Manhattan, spanning from the East River to Fourth Avenue and 14th Street in the north to Delancey and Clinton Streets in the south. Despite its small size, it is a racially and economically diverse area. In school year (SY) 2013–14, close to half (46%) of students attending elementary school were Hispanic, 22% were Asian, 16% black, 14% white, and 2% were another race. 72% of students were receiving free or reduced-price lunch in SY 2013–14 and 15% were homeless.

Unequal Distribution of Homelessness in District 1

Like New York City overall, District 1 experienced a rapid rise in child homelessness over the last four years. While overall elementary school enrollment remained roughly the same between SY 2010–11 and SY 2013–14, the number of homeless elementary students increased by 43%.3 By SY 2013–14 more than one in seven (15%) of the roughly 5,400 elementary students in District 1 were homeless. As seen in Figure 1, this rate is higher than the citywide average for homelessness among elementary students (9%); even more striking is that by school, District 1 had both some of the highest (47%) and lowest (0%) rates of homelessness in the city.

Homelessness Among Elementary Students in School District 1 (Figure 1)

*Because some schools in District 1 have fewer than 10 homeless students, school names for all 17 schools in the tables have been replaced with letters that can be compared across charts while maintaining student privacy in accordance with FERPA.

The precise reasons for the increase in homeless students are not known, but the neighborhood certainly shows many signs of gentrification. There have been significant changes in education, income, and rent levels within the district. Over a ten-year period between 2005 and 2015, the number of non-high school graduates dropped by 15% while the number of college graduates increased by 32%.4 In the same period, incomes rose by 32% and the cost of housing rose from a median rent of $664 in 2005 to $1,077 in 2015.5 Not only do these changes signal additional challenges for low-income families in maintaining adequate housing, but they also point to new demands on the district for high quality education situations for the influx of families with a higher economic status. Are these families moving into District 1 likely to choose a school where 47% of students are homeless?

In addition to widely different rates of student homelessness by school,* growth in homelessness varied dramatically across the district. Between SY 2010–11 and SY 2013–14 there was an increase of 236 homeless students. Figure 2 shows that just one school represented 29% of this increase, while other schools saw much lower rates of growth. Indeed, some schools actually witnessed a decline in the number of homeless students despite the 43% increase district-wide.

Proportion of Total Growth of Homeless Elementary Students (Figure 2)

Public School (P.S.) 188 is one elementary school in District 1 that has received attention in the last year for having one of the highest rates of student homelessness in New York City.6 Based on school size, Figure 3 shows that if homeless students were equally distributed across schools in the district, just 7% of all homeless elementary students would be expected to attend P.S. 188. Yet by SY 2013–14, over one–fifth of all homeless elementary students in District 1 attended this school. In fact, 47% of all elementary students at P.S. 188 were homeless, and 88% of students were eligible for free or reduced-price lunch. In other words, virtually half of the students at one school are at risk for falling behind academically, with lower assessment scores, higher grade retention and much higher rates of absenteeism. It is difficult to imagine that this is what the DOE envisioned when designing unzoned districts, but this is the outcome. Staff at schools such as P.S. 188 are working with large numbers of homeless students in one building, which requires a significant amount of resources that may or may not be available. Accounting for the number of schools and the size of the student body, District 1 has the most unequal distribution of homeless students across schools, making it the most segregated school district by housing status in New York City.

Unequal Distribution of Homelessness in District 1 Elementary Schools (Figure 3)

This de facto segregation is occurring within a district based entirely on choice. In theory, choice policy should reduce the concentration of homelessness or poverty in any one school by breaking the ties to specific geographic areas where family shelters are located or more families are living doubled up. Yet these data show the opposite. Why are homeless families not being engaged in the same choice process as housed families? What does this say about the structure of the system, access to information, and understanding of the choice process? Are homeless students somehow—unintentionally or otherwise—being pushed into predominately “homeless schools?” Considering the additional resources and structures already established at P.S. 188, could it be better for these students to remain concentrated in a school that is prepared to support them, with additional resources provided as necessary? To begin answering this last question, the DOE could consider the impact on academic outcomes of differing school environments for homeless students.

As a part of a larger plan to increase diversity by the New York City Department of Education (DOE) and some school principals, quotas are now being implemented at two District 1 schools—both the Earth School and the Neighborhood School will set aside 45% of seats for low-income families and English language learners.7 While this initiative may address some of the overarching economic segregation in the district, given the specific challenges that homeless students face—which often include late enrollment and limited access to online information—these changes will likely not address the district’s growing segregation by housing status.

What additional supports should be added to meet the needs of homeless students when choice systems are used for school enrollment? There will likely be more than one answer to this question—homeless families live in a variety of contexts and are presented with many different kinds of challenges. Supporting homeless students will never consist of a one-size-fits-all approach.

One example of a program supporting homeless students in choice enrollment processes is now being implemented by the DOE’s Office of Student Enrollment for high school applications. This program seeks to provide direct outreach to students living in shelters and one-on-one support to homeless students and parents at high school fairs to create each student’s school application list. While this is a promising approach for helping homeless families navigate choice systems, there will still be many families who may need additional assistance.

Families who become homeless after choice processes have taken place may require greater flexibility in where they send their child to school; those who miss the choice process altogether due to their unstable circumstances should not find their only enrollment options to be whichever schools have remaining open seats. In order for school choice systems to truly work for homeless families, a range of supports are necessary.

With over 87,000 homeless students attending New York City public and charter schools in SY 2013–14 alone, any policy that implicitly fails to address the unique needs of families struggling with housing instability must either be reconsidered or redesigned.8 If increasing diversity is now a stated goal, surely ending segregation by any measure must be part of the conversation. As the public appetite for choice increases, the ways in which homeless students, and other vulnerable populations, access choice must be incorporated into policy formulation and implementation. We cannot satisfy some parents with choice while leaving others out in the cold. Schools, teachers, students, and parents all suffer when a well-intentioned policy has such dramatic unintended consequences as the segregation by housing status seen in District 1.