The only way that educational supports can be effective is if they actually reach the students who need them. Unfortunately, it seems that supports such as English language learning (ELL) and special education services may be missing opportunities to effectively reach young students who are homeless.

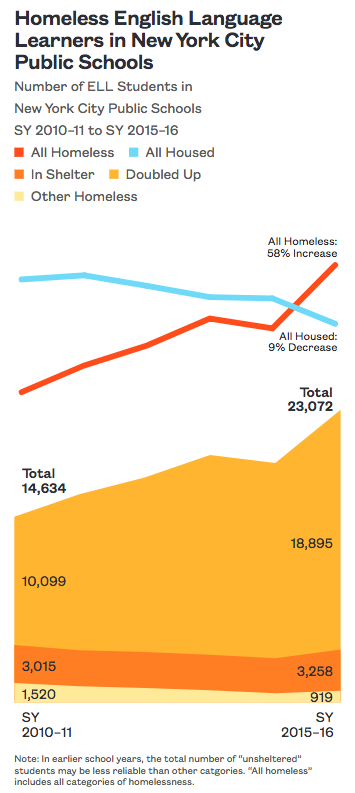

While putting together our third annual Atlas of Student Homelessness in New York City, I was surprised to discover that one in every six English Language Learners is homeless—more than 23,000 students in school year 2015–16. Additionally, homeless students are receiving English language learning (ELL) services across all languages for longer than their housed classmates. We had already identified a similar, troubling trend looking at special education needs, finding that students who were homeless were more likely to be identified as needing an Individualized Education Plan (IEP) late, or after Kindergarten, missing out on years of additional supportive instruction.

Why do homeless students face such challenges in receiving additional supports? Why do they receive IEPs late or receive ELL services for longer?

One reason that can’t be ignored is the school instability that comes with living in temporary housing. Many homeless students are frequently absent and transfer schools mid-year. Missing class or being new at school makes it difficult for teachers to identify a need for extra support. They may not realize that homeless students are falling behind not just because they are absent, but because they need an IEP or have trouble reading and understanding English.

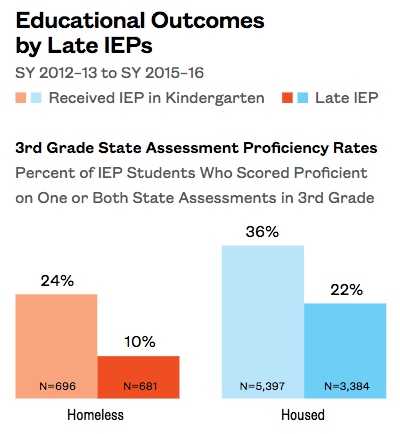

After looking at the data in New York City, the nation’s largest public school system, it is clear that these services make a difference for kids. Using State assessment pass rates, one measure of achievement, we saw that homeless students who faced difficulty in receiving services were far less likely to be proficient, especially among those who received late IEPs or were still receiving ELL services by fifth grade.

There is a tremendous overlap between students with additional service requirements and those who have lived in homeless settings. Children living in temporary housing who have additional educational or language learning needs are not less smart than their classmates, they just need a fair chance. When students receive the supports they need, they score proficient more often. School administrators, teachers, and policy makers must consider how homeless students will receive those services, if programs are to truly benefit every child and improve outcomes citywide.

Rachel Barth, Policy Analyst