By Maribel Maria, Policy Associate, and Caroline Iosso, Senior Policy Associate

Pregnancy is often a time of joy and anticipation, but for homeless or housing insecure parents, it can bring new stressors, especially regarding finances. Guaranteed income is a policy that has the potential to mitigate some of the costs associated with pregnancy, childbirth and recovery, childcare, and adding a new member to a family. This blog will delve into the concept of guaranteed income and its potential benefits for families, especially those experiencing homelessness or on the precipice.

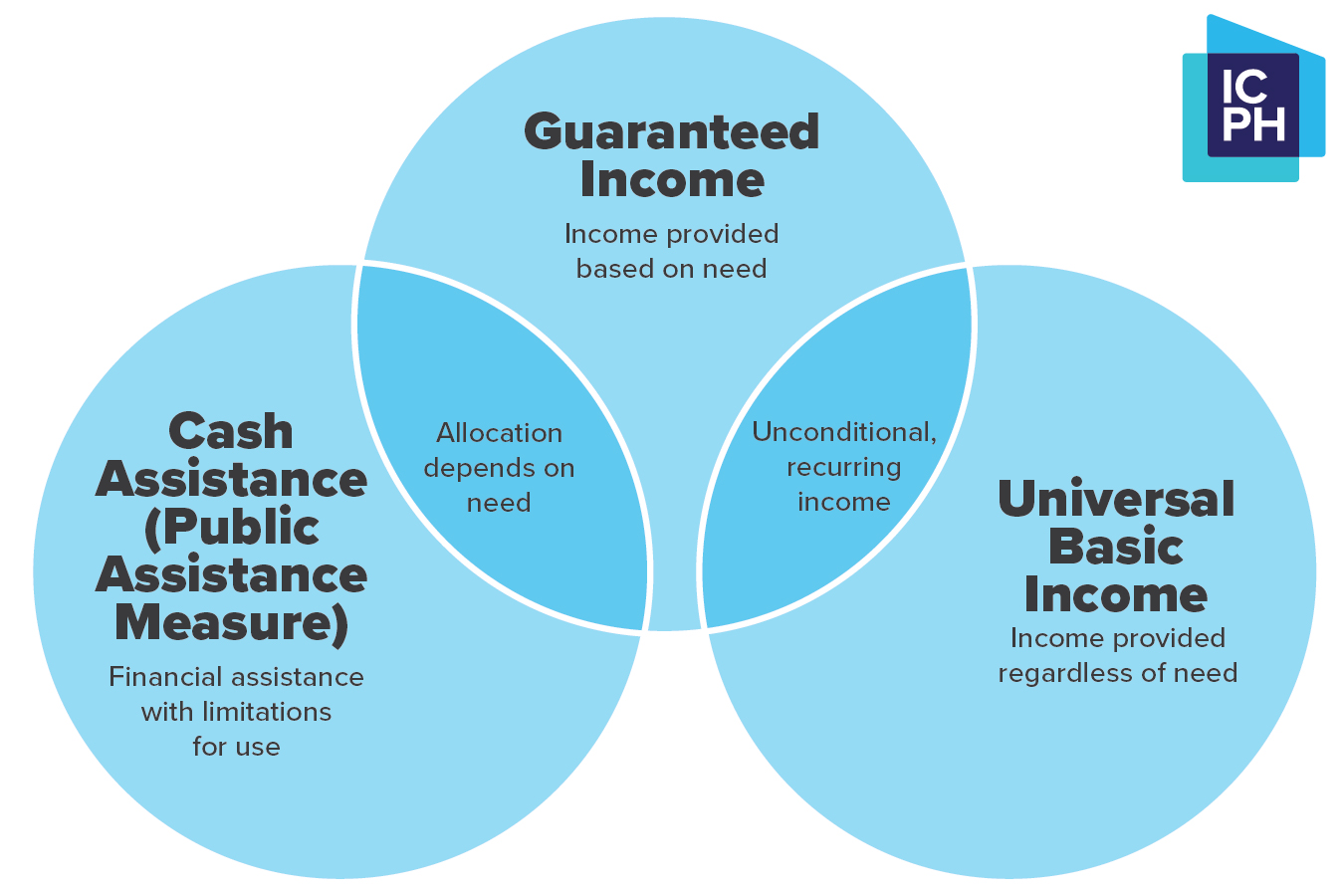

Guaranteed income is a recurring cash payment with no conditions for its use. It is given to people based on characteristics such as poverty level or a particular health status. This differs from often associated terms like universal basic income, which provides cash payments to all people regardless of need.1

Relieving financial strains for families with children is critical to their overall well-being. Poverty and homelessness can take a toll on the mental and physical health, academic and career outcomes, and rates of returning to shelter for both parents and children.2,3,4,5,6Among these and other factors, children who experience homelessness are vulnerable to chronic health problems, developmental delays, and academic difficulties in comparison to their peers.7,8 Critical development occurs in the early years of a child’s life, making postpartum and early parenthood especially important times for a parent to be stable, healthy, and housed. Poverty and homelessness during pregnancy is risky for expectant parents, as it can increase the chance of delivering prematurely and experiencing complications during childbirth.9 As such, it is important to explore ways of mitigating the effects of poverty and homelessness on families during pregnancy and early childhood.

Guaranteed Income Pilot Programs and Existing Research

Several pilot programs have emerged to evaluate the effectiveness of providing pregnant people and families with no-strings-attached cash. The Abundant Birth Project, a California-based pilot by Expecting Justice, supplies nearly 150 pregnant and postpartum people from Black and Pacific Islander communities that have faced disproportionately high rates of adverse birth outcomes with unconditional payments of $1,000 a month. It is currently being evaluated to determine how guaranteed income affects health and economic outcomes in the Black and Pacific Islander communities.10 Another pilot is The Bridge Project, New York’s first “unconditional cash allowance program.”11 The program provides new mothers with unrestricted cash payments for the first three years of their child’s life. The Bridge Project, like many other guaranteed income pilot programs, emphasizes the importance of flexibility to its model. Unrestricted payments allow parents to choose how to spend their money—whether it be on groceries, rent, medical expenses, childcare, or emergency savings. Neither program is specifically targeting families in shelter. For both programs and several other pilot studies looking at the effects of guaranteed income, results are still pending. However, the emphasis on supporting pregnant people is a promising approach.

Worth mentioning as well is the Magnolia Mother’s Trust. Although it does not specifically focus on pregnant families, it is the longest running guaranteed income program in the country and has served as a national model. The initiative provides low-income Black mothers in Jackson, Mississippi with $1,000 monthly for a year. The program has proved extremely beneficial to participating families, with mothers reporting greater confidence and hope and stronger relationships with their children, in addition to their financial gains. As a result of the program, more mothers can pay their bills on time, put money in savings, and lower their debt.

Recent studies on cash transfer use by people experiencing homelessness or poverty show that spending is most typically on necessities, instead of luxury items or “temptation goods” like alcohol. In a study in Canada in which 50 individuals experiencing homelessness received a one-time unconditional $7,500 (Canadian dollars), recipients spent fewer days homeless, increased savings, and did not increase their spending on temptation goods.12

In another study that provided participants with $500 per month for two years, recipients spent less than 1% on tobacco and alcohol.13 These findings contradict harmful stereotypes about the spending habits of people experiencing poverty or homelessness, who have long been subject to judgement by policymakers and the public about whether they are deserving of assistance programs or other forms of poverty relief.15 They also show the effectiveness of unrestricted cash payments in helping people.

In thinking about the potential impacts of no-strings cash assistance on new families, we should also consider how extra cash directed at households through the federal child tax credit improved many families’ overall well-being.14 The tax credit was expanded in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Under the American Rescue Plan, families received $3,600 for every child under 6 years old and $3,000 for every child over 6 years old, half of which was delivered through a monthly cash payment advance and half of which was a tax credit. This expansion helped to significantly reduce the national child poverty rate, reaching a historic low of 5.2% in 2021 and showing improvements across racial groups.16,17 Research showed that families spent the monthly checks on food and basic needs, and struggled to make those purchases when payments stopped.18

Potential Impacts of Guaranteed Income: Empowering Pregnant Parents and Promoting Ongoing Stability

A steady infusion of cash into the pockets of pregnant parents has the potential to dramatically improve their lives and the lives of their families, mitigating the harmful effects of poverty and homelessness during the critical early years of children’s development. Receiving guaranteed income provides families with a level of autonomy that they may not have when using traditional housing or nutrition assistance programs. In situations where a budget may be in flux due to the changing needs of a family, a recipient of guaranteed income can decide that they will use a portion of the income for that period on a new need—such as a safe crib or bassinet for their new baby—whereas in the case of a supplemental nutrition assistance recipient, they may have to leave unspent money for their next grocery run. This type of self-determination helps move conversations about the economic and social wellbeing of pregnant parents experiencing poverty or at risk of homelessness away from conditional support and judgment of their worthiness.

Guaranteed income could promote stability among pregnant parents and families, helping to sustain families during periods when their regular income may be limited or uncertain. Pregnant parents are particularly susceptible to losing their source of income due to the need for extended time off for medical issues or discrimination in the workplace. This can continue after birth since many may face problems related to a lack of accessible childcare or inadequate parental leave. Income volatility can be stressful for any family, but experiencing it while pregnant or postpartum can negatively impact the emotional and physical wellbeing of parents as well as that of the new child.19

Exposure to this type of stress can lead to physical and mental health problems that trickle down to children. In a lived experience perspective shared in the Healthy Parents, Healthy Babies project, a parent named Rodrika recounted how her anxiety around losing housing as a child affected her ability to provide stability as a parent herself.20 Guaranteed income can further ensure family stability in the early years of a child’s life by gradually reducing support instead of immediately cutting off aid at the end of pregnancy. This can provide a smoother transition for families as they develop the necessary skills or take the time they need to achieve future independence.

Offering guaranteed income for pregnant parents has the potential to be a powerful tool in lifting families out of poverty, improving health outcomes, and supporting child development. A pilot program that focuses on pregnant parents currently experiencing homelessness could help demonstrate even more strongly the connection between unconditional, consistent financial support and housing security, economic mobility, and health.

1 Arlington Community Foundation. (2023). Guaranteed income vs universal basic income. Arlcf.org. https://www.arlcf.org/guaranteed-income-vs-universal-basic-income/

2 Institute for Children, Poverty & Homelessness. (2023, May 25). Homeless students and absenteeism. https://www.icph.org/commentary/homeless-students-and-absenteeism/

3 Institute for Children, Poverty & Homelessness. (2015). Effects of homelessness on families and children. www.icphusa.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Effects-of-Homelessness.pdf

4 National Alliance to End Homelessness. (2023, April). Children and families. https://endhomelessness.org/homelessness-in-america/who-experiences-homelessness/children-and-families/

5 Early Childhood Learning and Knowledge Center. (2018, July 2). Caring for the health and wellness of children experiencing homelessness. National Center on Early Childhood Health and Wellness. https://eclkc.ohs.acf.hhs.gov/publication/caring-health-wellness-children-experiencing-homelessness

6 Clark, R. E., Weinreb, L., Flahive, J. M., & Seifert, R. W. (2019). Homelessness contributes to pregnancy complications. Health Affairs, 38(1), 139–146. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05156

7 Institute for Children, Poverty & Homelessness. (2015). Effects of homelessness on families and children. www.icphusa.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Effects-of-Homelessness.pdf

8 Early Childhood Learning and Knowledge Center. (2018, July 2). Caring for the health and wellness of children experiencing homelessness. National Center on Early Childhood Health and Wellness. https://eclkc.ohs.acf.hhs.gov/publication/caring-health-wellness-children-experiencing-homelessness

9 Clark, R. E., Weinreb, L., Flahive, J. M., & Seifert, R. W. (2019). Homelessness contributes to pregnancy complications. Health Affairs, 38(1), 139–146. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05156

10 University of California San Francisco. (2023, September 21). About the Abundant Birth Project evaluation study. https://abundantbirtheval.ucsf.edu/about

11 The Bridge Project. (2023, November 7). Our work. https://bridgeproject.org/our-work/

12 Dwyer, R., Palepu, A., Williams, C., Daly-Grafstein, D., & Zhao, J. (2023). Unconditional cash transfers reduce homelessness. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 120(36), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2222103120

13 West, S., Castro Baker, A., Samra, S., & Coltrera, E. (2021). Preliminary analysis: SEED’s first year (pp. 1–22). Stockton Economic Empowerment Demonstration (SEED). https://static1.squarespace.com/static/6039d612b17d055cac14070f/t/603ef1194c474b329f33c329/1614737690661/SEED_Preliminary+Analysis-SEEDs+First+Year_Final+Report_Individual+Pages+-2.pdf

14 See, for example: Nunez, Ralph DaCosta, and Ethan G. Sribnick. The Poor among Us: A History of Family Poverty and Homelessness in New York City. White Tiger Press. (2013).

15 Internal Revenue Service. (2023, August 24). Child tax credit. www.irs.gov/credits-deductions/individuals/child-tax-credit

16 Trisi, D. (2023). Government’s pandemic response turned a would-be poverty surge into a record poverty decline. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. www.cbpp.org/research/poverty-and-inequality/governments-pandemic-response-turned-a-would-be-poverty-surge-into

17 Parrott, S. (2023, September 12). Record rise in poverty highlights importance of child tax credit; health coverage marks a high point before pandemic safeguards ended [Press release]. Cbpp.org; Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. www.cbpp.org/press/statements/record-rise-in-poverty-highlights-importance-of-child-tax-credit-health-coverage

18 Center on Poverty & Social Policy at Columbia University. (2022, November). One Year On: What we know about the expanded Child Tax Credit. https://www.povertycenter.columbia.edu/news-internal/2022/child-tax-credit-research-roundup-one-year-on

19 Jimenez, N., Jones, K., & Poppe, B. (2023). Healthy parents, healthy babies (pp. 1–29). National Alliance to End Homelessness. https://endhomelessness.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/Healthy-Parents-Healthy-Babies-Final-Report-7.15.23.pdf

20 Ibid.