The instability of homelessness can have lasting effects on a child’s academic performance. Not only can the stress of lacking a stable place to sleep impact their ability to focus on school, homelessness can negatively affect a child’s cognitive development. Additionally, homeless children are more likely to miss school than their housed peers, leaving them at an even greater risk of falling behind academically.

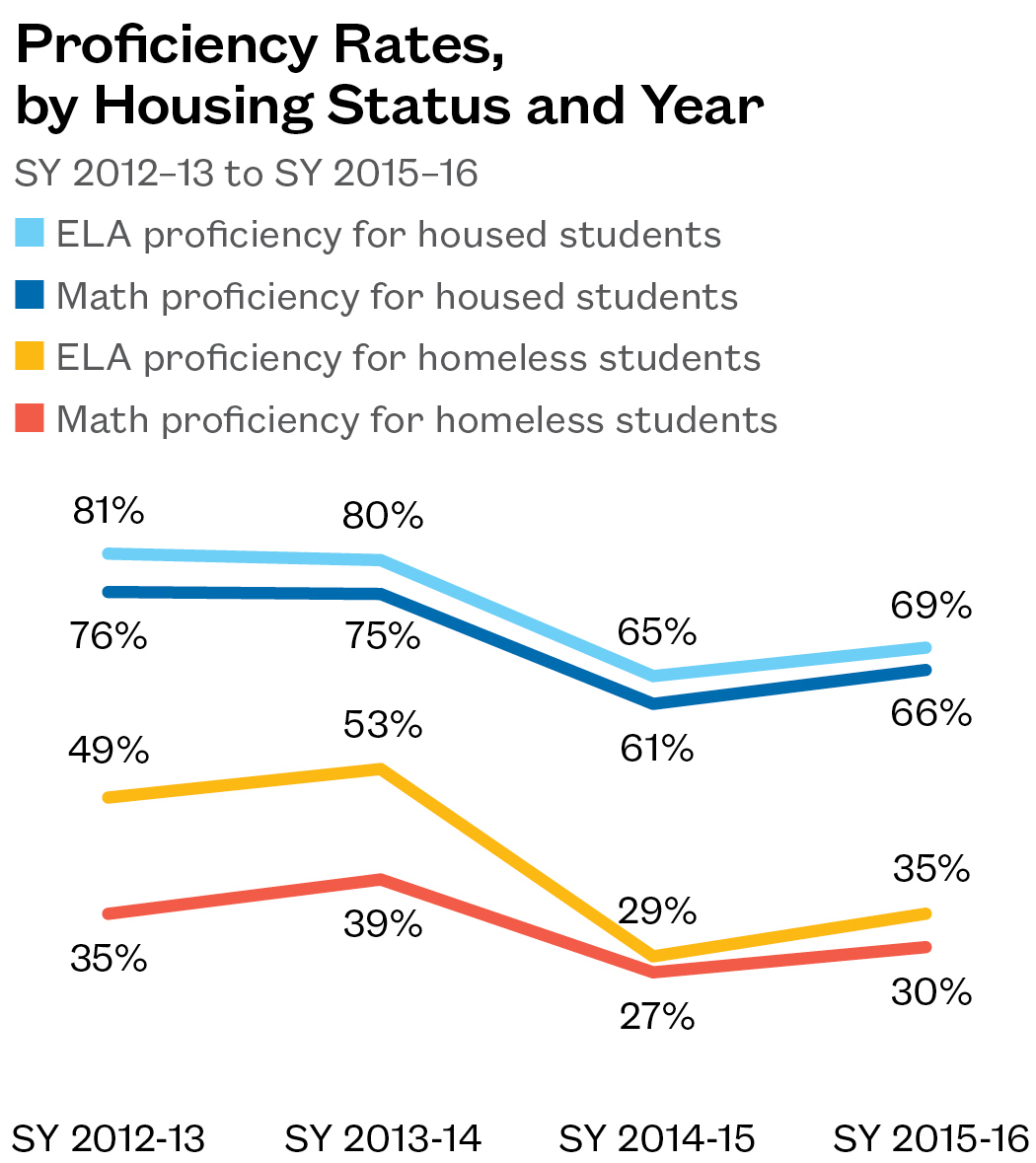

Throughout the country, students enrolled in grades 3–8 are required to take annual standardized tests that measure whether they are performing on grade level in math and English Language Arts (ELA). In Seattle Public Schools (SPS) from SY 2012–13 to SY 2015–16, the proficiency rate of homeless students was half that of their housed peers. Citywide, fewer than one-third of homeless students achieved grade-level proficiency in math, and just 35% met the grade-level standard in ELA. This vast disparity in proficiency rates between housed and homeless students persisted even after Washington state adopted the Common Core Curriculum in SY 2014–15.

When we break down these test results by achievement levels and housing status, the disparity between housed and homeless students becomes even more apparent. Forty-two percent of homeless students in Seattle received the lowest achievement level in both math and ELA. Housed students were four times more likely than homeless students to perform at the highest achievement level.

Across races and subjects, housed students performed better than their homeless peers. Black homeless students were the least likely to meet the grade-level standard, with just 23 percent passing the standardized test for math and 26 percent passing ELA. Meanwhile, around one in three Hispanic homeless students scored proficiently on either test. About half of white homeless students met the grade-level standard. The passing rate among homeless white students is about the same or better than their black and Hispanic peers who were housed. These results raise interesting questions about the extent to which race and housing status influence a child’s academic performance.

Seattle has recognized the “opportunity gap” that exists between its white students and students of color, and is taking steps to address this inequity. After a 2016 study by Stanford University found that Seattle had the 5th-highest achievement gap in the country, SPS launched its #ClosetheGaps campaign, to ensure high-quality education for all students. The campaign uses a variety of strategies to achieve this goal, including mentorship programs, a social-emotional curriculum, and an attendance program to reduce high rates of chronic absenteeism.

It is encouraging that SPS has acknowledged the need for additional training and supports for homeless and minority students. As more homeless students are connected with services and administrators invest in ways to better engage students of color in the classroom, there is reason to be hopeful that all students, regardless of housing status or race/ethnicity, will be given an equal chance to succeed.

Chloe Stein, Policy Analyst