Letter from the Executive Director

Dear Reader,

Welcome to the January 2025 issue of Beyond Housing—a platform dedicated to fostering ideas and solutions to address family homelessness, continuing the essential dialogue initiated by our previous conferences of the same name. This month, ICPH and HFH are thrilled to participate in the National Women’s Shelter Network (NWSN)’s “United for Women, Families, and Children” conference in Washington, DC.

This issue’s theme emerged from a prep session for the “Shelter as Sanctuary” panel, which I am honored to moderate. During the panel, I will present HFH’s approach and highlight our Allie’s Place Family Residence alongside three nonprofit leaders from Mary’s Place (Seattle), Lotus House (Miami), and Atlanta Mission (Atlanta). Our collaborative discussions underscored the shared commitment among our organizations to redefine the role of shelter and deliver comprehensive services. Recognizing the value of these insights, we decided to offer our conference attendees and loyal readers an in-depth exploration of these models instead of a simple one-page takeaway.

Common threads among all four organizations include intentionality in our design, a focus on children, and a holistic approach to supporting both staff and clients as the multifaceted individuals they are. While no one organization can claim to have it all figured out, I am deeply inspired by the opportunity to share what I’ve learned and gain new perspectives through collaborations like this.

Learning and sharing defines ICPH’s mission. As we shape our future, it remains at our core.

We welcome your feedback and invite you to connect with us on Instagram, LinkedIn, or via email at Info@ICPH.org. Visit us online at ICPH.org to learn more about our work.

Sincerely,

John Greenwood

Executive Director

Institute for Children, Poverty & Homelessness and Homes for the Homeless

A Comprehensive Strategy to Combat Family Homelessness: Mary’s Place’s Three-Pronged Approach

By: Linda Mitchell

In the heart of King County, the most populous county in Washington State, a crisis unfolds daily as families find themselves without a place to call home. The situation has reached unprecedented levels, with 50–60 unique families calling the emergency family intake line each day. Yet, due to limited capacity, only two or three families can find shelter, leaving many others to face the harsh reality of sleeping outside. This growing crisis represents not just a housing emergency, but a public health crisis with long-term and generational impacts on children.

The impacts of family homelessness on children are particularly devastating and can echo throughout their lives. When children experience the trauma of homelessness, their physical, emotional, and academic development often suffers. Unstable housing situations can lead to frequent school changes or extended absences, disrupting their education and social connections. The stress of homelessness can manifest in behavioral changes, anxiety, and depression as well as increased risks of chronic health conditions. Environmental stressors such as inadequate nutrition and exposure to unsafe living conditions further compound these risks.

Perhaps most concerning is the long-term, intergenerational impact—children who experience homelessness are more likely to face housing instability as adults, perpetuating a cycle that can span generations. This makes addressing family homelessness not just a housing issue, but a critical public health concern that demands immediate and comprehensive intervention. Mary’s Place, a leading organization in the fight against family homelessness, has developed a sophisticated three-pronged approach to address this growing crisis: emergency shelter, mobile outreach, and homelessness prevention.

The First Prong: Emergency Shelter – A Safe Haven for Families

At the foundation of Mary’s Place’s strategy lies its network of three 24/7 shelters providing 650 beds each night to families in crisis. These shelters serve as more than just a roof over heads; they provide comprehensive support to help families begin rebuilding their lives. The shelters represent the last line of defense against the trauma of unsheltered homelessness, providing crucial stability and safety for families at their most vulnerable moments.

Upon arrival, families are immediately connected with staff advocates who help them navigate their challenges and search for affordable housing solutions. These advocates work tirelessly to understand each family’s unique situation, identifying barriers to housing and developing personalized plans to overcome them. Understanding that homelessness affects every aspect of family health and well-being, Mary’s Place maintains an on-site health team that provides physical and behavioral health services, appointment coordination, and referrals at each location, ensuring families receive the care they need during their stay.

The organization has also developed specialized programs to address unique needs within the community. The innovative Popsicle Place program was created after discovering families living in their cars outside hospitals while awaiting medical treatments for their children. This program specifically supports families with medically fragile children and works to prevent hospital discharge to homelessness. The program has become a model for addressing the intersection of medical care and housing stability, ensuring that no family has to choose between medical treatment and a place to live. Similarly, the Baby’s Best Start program provides targeted support for pregnant women and new parents, offering education and care coordination to help new families bond and thrive.

Kids Club provides age-appropriate activities, homework assistance, and recreational opportunities, working to maintain a sense of normalcy for children experiencing homelessness. The organization also coordinates with local school districts to ensure educational continuity and necessary transportation for school-aged children. These youth services extend beyond basic education to include enrichment activities like Science Club and Girl Scouts, providing children with opportunities for growth and development despite their challenging circumstances.

The Second Prong: Mobile Outreach – Meeting Families Where They Are

“We cannot continue to address the growing number of unsheltered families with shelter. It’s just not sustainable,” says Dominique Alex, Mary’s Place CEO. “We must implement strategies, like Prevention, that stop the flow of families into homelessness.”

With shelters consistently at capacity, Mary’s Place developed its second strategic approach: a mobile outreach team that takes support directly to unsheltered families. This team serves as a lifeline for families living in cars and tents, providing essential supplies like diapers, blankets, and tents, and connecting them with housing resources. The mobile outreach team plays a crucial role in building trust with families who might otherwise remain hidden from support services, often out of fear of losing their children or stigma associated with homelessness.

In many cases, the mobile outreach team can help families overcome immediate financial barriers, such as security deposits or car repairs, enabling them to move back into housing quickly without requiring a shelter stay. This rapid-response approach has proven particularly effective in preventing families from falling deeper into crisis, addressing urgent needs while simultaneously working on longer-term housing solutions.

The team’s work extends beyond immediate assistance to include comprehensive case management and resource navigation. They help families access available public benefits, connect with healthcare providers, and navigate the complex web of social services. This approach not only helps families avoid the trauma of extended homelessness but also proves more cost-effective than emergency shelter services. The mobile outreach team serves as a crucial bridge between unsheltered families and the resources they need to regain stability.

“By creating spaces where kids can simply be kids and forget about the stress they experience from being homeless, we work to minimize the generational psychological impact that the trauma of homelessness can have on children.” – Zoë Bill, Youth Services Director, Mary’s Place.

The Third Prong: Prevention – Breaking the Cycle Before It Begins

Perhaps the most crucial element of Mary’s Place’s strategy is its focus on prevention. Studies consistently show that experiencing homelessness in the past significantly increases the likelihood of facing homelessness again in the future. For instance, a systematic review of predictors of homelessness published in the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health identifies prior homelessness as a critical factor, reflecting its role as a strong predictor of future housing instability.

By helping families maintain their current housing, Mary’s Place works to prevent both immediate crisis and generational homelessness. This preventive approach represents the most cost-effective and humane way to address family homelessness, intervening before families face the trauma of losing their homes and their communities.

The prevention program’s effectiveness was particularly evident during the COVID-19 pandemic, when emergency rental assistance and other financial supports helped keep families housed. This period demonstrated clearly that with adequate resources and support, many families can avoid falling into homelessness altogether. However, as these supports have ended, the community is witnessing the devastating impact of their absence, with more families falling into homelessness.

Prevention and stability support services can address financial emergencies before they lead to eviction. The prevention program includes financial education and planning support, helping families build long-term stability while addressing immediate needs. And helping families maintain stability is cost effective. Keeping a family in their home is less than half the cost of shelter services.

Mary’s Place has partnered with the University of Notre Dame’s Lab for Economic Opportunity (LEO) for a three-year study to look at the most effective ways to distribute rental support to prevent homelessness. This work builds on a growing body of research on the effectiveness of rental assistance and guaranteed basic income. The organization has just completed year one of the research.

“We’re looking to sharing the findings of this research with policy makers to promote meaningful action on this critical strategy for addressing homelessness,” says Alex. “Prevention keeps families in their homes, preventing the trauma of displacement, and allowing families to breathe…and thrive in their communities.”

Understanding the Root Causes

We can’t adequately address our current crisis of family homelessness without understanding how we got here. A severe lack of affordable housing combines with high inflation affecting essential needs like food and diapers, while wages have failed to keep pace with the cost of living. Many families lack adequate safety nets, both financial and familial, making them vulnerable to housing instability. Even a minor emergency, such as a car repair or medical bill, can trigger a cascade of financial challenges that lead to homelessness.

The aftermath of expired COVID-19 protections has further exacerbated the situation. The end of eviction moratoriums and emergency rental assistance programs has left many families struggling to maintain housing stability in an increasingly challenging economic environment. Additionally, the historic and ongoing impacts of systemic racism leads to disproportionate impacts on Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC). More than 80% of guests at Mary’s Place shelters identify as BIPOC. Historical practices like redlining, ongoing discrimination, and limited access to opportunities have created barriers that continue to affect housing stability for these communities.

A Coordinated Response

Mary’s Place’s success relies not just on their three-pronged approach, but also on their extensive partnership network. They collaborate with local providers and organizations to create a comprehensive support system. Through these partnerships, they offer pro bono legal assistance, ESL classes, mental health services, and job training programs to their guests. Community and corporate volunteers provide additional support through workshops focusing on financial literacy, computer skills, resume development, and interview preparation.

These partnerships extend beyond direct services to include advocacy and systems change work. By working with local governments, businesses, and other nonprofits, including affordable housing providers, Mary’s Place helps build a more coordinated and effective response to family homelessness.

Public Funding

“The harsh reality is that nonprofit service providers simply cannot shoulder the enormous financial burden of addressing family homelessness alone,” says Dominique Alex, CEO of Mary’s Place. “Our current funding model—where we rely on private donations and foundations for over 80% of our budget—is unsustainable and inadequate to truly tackle the systemic challenges of family homelessness.”

Alex points to a transformative example in Santa Clara County, California, where Destination: Home successfully transitioned from a primarily privately funded initiative to a robust public-funded program through strategic partnerships. “This isn’t just a funding model—it’s a blueprint for meaningful, large-scale intervention,” she emphasizes. “We need Washington to recognize that solving family homelessness requires a collective commitment, with public resources matching the passion and dedication of community organizations.”

Looking Forward

Mary’s Place emphasizes that no single approach can solve the family homelessness crisis. Instead, all three prongs—shelter, mobile outreach, and prevention—must work in concert to create lasting change. While emergency shelter provides immediate safety and support, mobile outreach helps reach families who can’t come inside, and prevention works to stop homelessness before it begins and stop the flow of families falling into homelessness.

As the community continues to grapple with rising housing costs and economic challenges, the need for comprehensive approaches like Mary’s Place’s three-pronged strategy becomes increasingly clear.

The organization’s work demonstrates that with the right combination of immediate intervention and long-term support, family homelessness can be addressed effectively. However, it also highlights the ongoing need for systemic changes and continued community support to ensure that all families have access to stable housing.

Mary’s Place’s comprehensive approach demonstrates that ending family homelessness requires both immediate intervention and long-term strategic thinking. Their work highlights an essential truth: children should not be sleeping outside in our community, and with the right combination of resources and strategies, they don’t have to be. Mary’s Place is not just providing emergency assistance but working to break the cycle of homelessness for future generations.

Note: Citations and sources for data are included in the PDF version of this document available by clicking Downloads below the Table of Contents.

Beautiful Resilience: 20 Years of Lotus House

By Robyn Schwartz with additional research by Thomas Simmons

From a seedling planted 20 years ago, Lotus House Women’s Shelter has blossomed into Lotus Village, the largest women’s shelter in the United States. The organization provides shelter to over 1,500 women, children, and youth every year and will expand its current community outreach offerings to scores of additional Miami residents through its nonresidential programs at the new Children’s Village in early 2025. At the dawn of 2025, Lotus House and its affiliates are seemingly everywhere, from namechecks in U.S. Supreme Court friend-of-the-court briefs to the society pages (supermodel and philanthropist Gisele Bündchen is a supporter and board member of affiliate and supporting foundation Lotus Endowment Fund, Inc.).

Lotus House devotes its efforts to women of all ages, youth ages 18–24, and pregnant and parenting mothers with children. The organization’s “children first” ethos is apparent in its Children’s Wellness Center and programmatic focus for its youngest guests— half of the 525+ sheltered nightly by Lotus House are children and over 380 babies and counting have entered the world with Lotus House as their first home. The Rainbow Lotus Program extends nurturing, sensitivity, and community linkages to the LGBTQIA+ individuals sheltered at Lotus House and may have histories of dual marginalization due to their identities and housing status. Its latest undertaking, Children’s Village, will be a neighborhood resource center featuring a fully accessible playground and housing over 10 nonprofits focused on providing supportive services and educational enrichment opportunities to local children and families, whether they reside at Lotus House or in the wider community.

Who is Lotus House? A Brief History

Following two-plus decades of private legal practice, real estate investment and finance, in 2004 a chance encounter with a woman experiencing homelessness led Constance Collins to make a career 180. She used her business acumen to purchase a property in Miami, Florida’s historically-Black and underserved Overtown neighborhood, which she and other volunteers transformed into a 34-bed homeless shelter for single women. Lotus House opened in 2006, and just one year later the organization debuted another program focused on homeless pregnant women and their children, nearly doubling the number of guests served. Lotus House continued to grow into its current state of the art comprehensive homeless facilities—sheltering 525+ women, youth, and children nightly—called Lotus Village. Collins is a recipient of ICPH’s 2018 Beyond Housing Award for Philanthropy. Today, she serves as president of the shelter’s parent organization Sundari Foundation, Inc. dba Lotus House and its supporting foundations, Lotus Endowment Fund, Inc., and various subsidiaries as well as President and Executive Director of the National Women’s Shelter Network (NWSN). Founded in 2022, NWSN champions Lotus House’s “beyond housing” approach to the critical need for trauma-informed wraparound support and enriched services to help women and families exit homelessness and maintain both housing and holistic stability.

The shelter’s name draws inspiration from the pink lotus flower (Nelumbo nucifera), an international symbol of compassion. The calm and soothing shade of pink can be found throughout the organization’s programming, living, and workspaces as well as on staff, volunteer, and collateral material. The shelter’s spaces and culture are designed to be anything but institutional, exuding an attention to inviting aesthetics. The rooms and hallways filled with art gifted or on loan from serious collectors as well as mini masterpieces created by the children staying there reflect what happens inside—a refreshing and ever-evolving approach to helping women and children overcome barriers and plant themselves in a better future.

The Need in Miami

Child Poverty

As of 2023, Miami’s child poverty rate was 22%—higher than the 16% child poverty rate registered in both Florida and the overall United States. The city’s general poverty rate for the entire population was nearly 18% according to the 2023 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates.

Neighborhood Disadvantage

The Overtown zip codes of 33136, 33142, and 33147—where nearly one-third of Lotus House residents indicated they last resided prior to entering shelter—are among the Miami communities that according to the 2024 Miami Matters health indexes were the most food insecure (all three fell within the top 10 most disadvantaged neighborhoods), least healthy (33136 and 33142 had the top two worst health outcomes in the region), and recorded the greatest reports of poor mental health (all three landed within the top 10 zip codes).

Trends in Homelessness

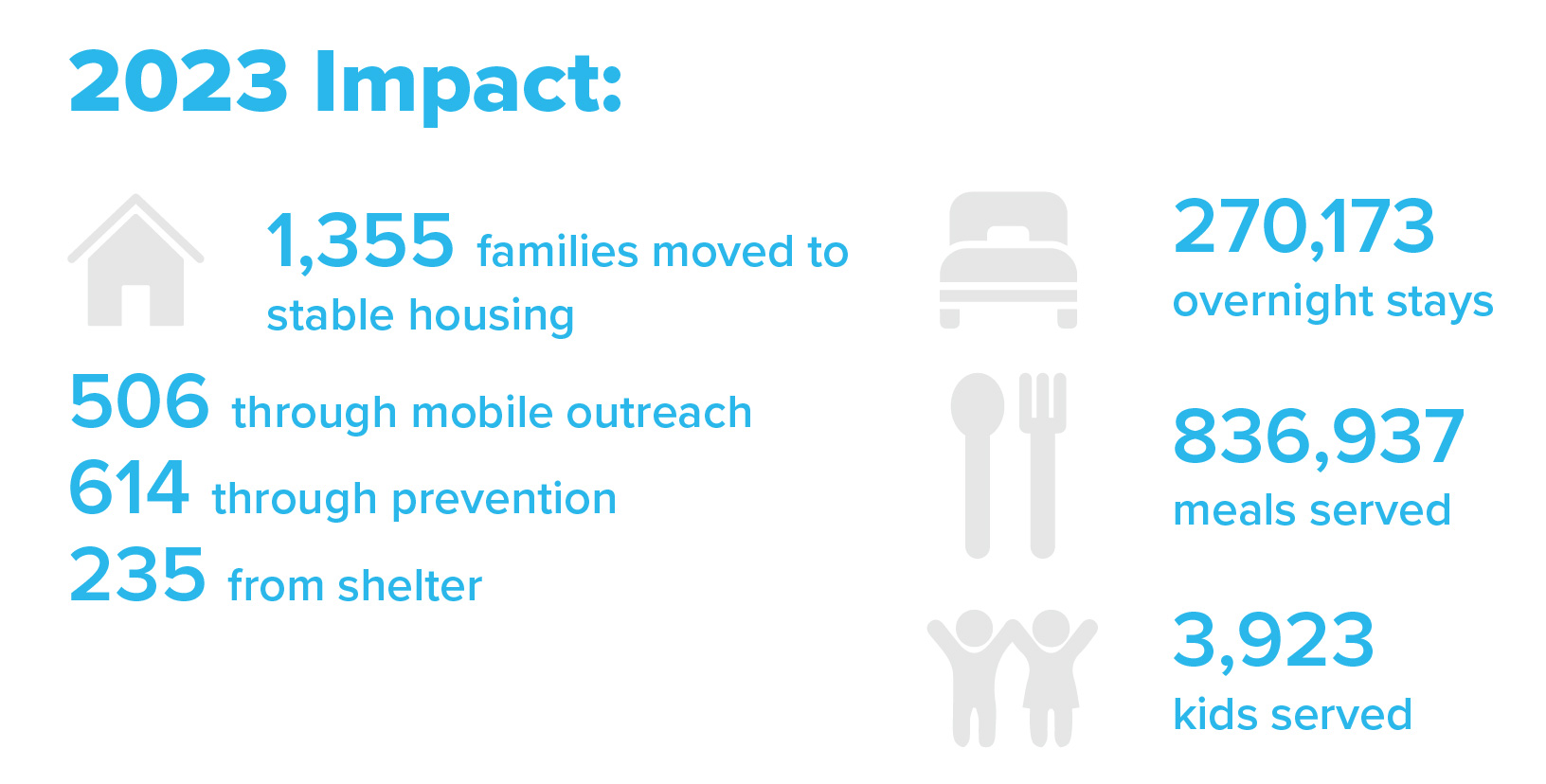

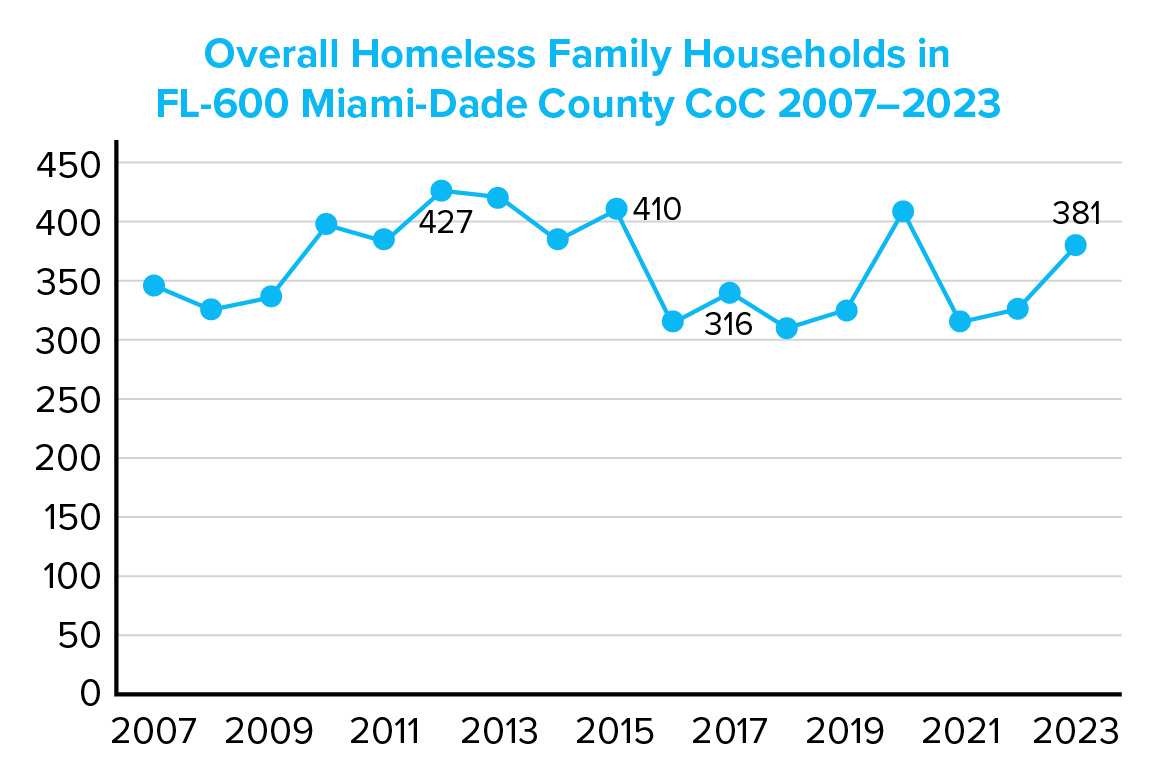

Although the accuracy of the federal Annual Homeless Assessment Report to Congress (AHAR) estimates have been questioned by various observers as a vast undercount, the numbers are often the best gauge communities have to help them consistently track their homeless census over time. For the FL-600 Miami-Dade County Continuum of Care (CoC), the overall Homeless Family Households from 2007–2023 PIT Counts by CoC have held relatively steady. The average number of Homeless Family Households over this period was 363. The highest recorded number of households was 427 in 2012. The Miami-Dade County Homeless Trust Census indicates that the number of Homeless Family Households was 409, an increase of 28 homeless families—or 7%—from 2023. Note: the 2024 AHAR report was released at the time of publication so was not included in this article.

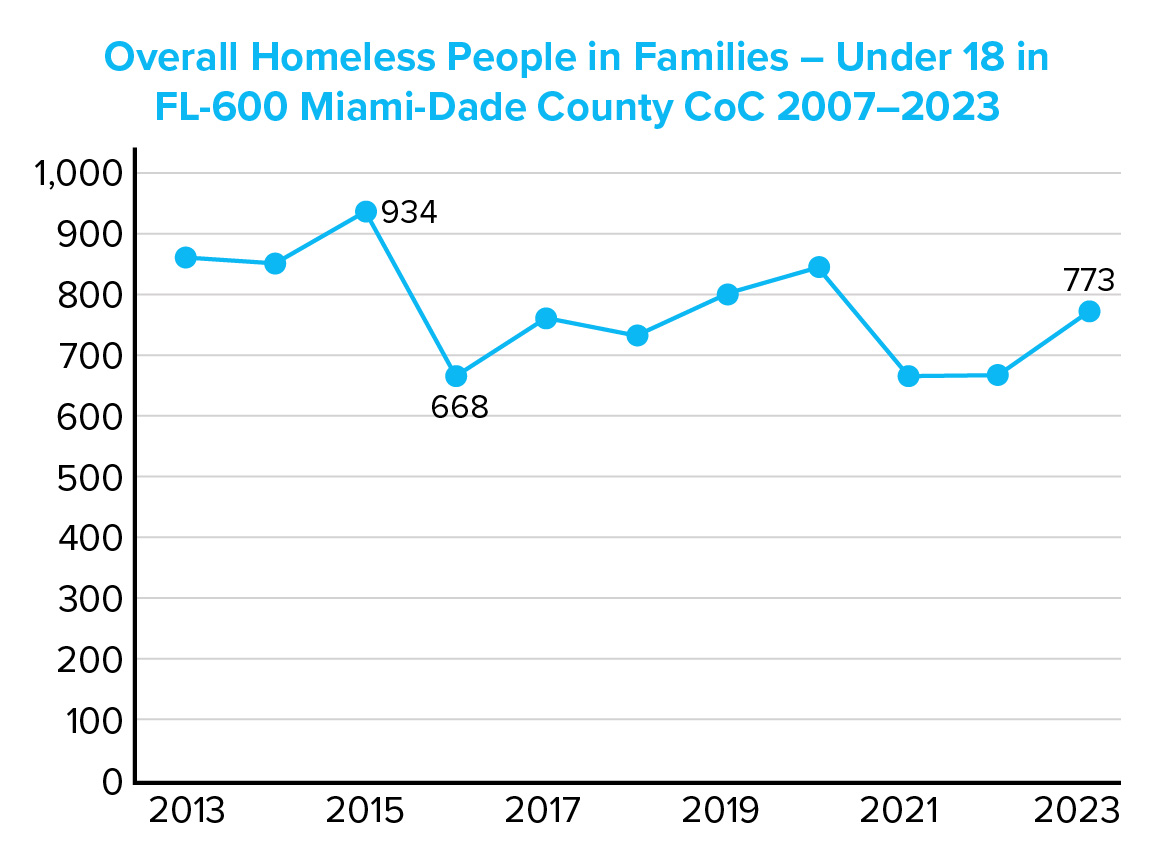

The average number of children experiencing homelessness who are part of homeless families in Miami between 2013 and 2023 was 778 (Overall Homeless People in Families – Under 18), almost the same number as the currently available figure of 773 (the 2024 figures released by the Miami-Dade County Homeless Trust Census do not include a breakdown by age).

Sources: 2007 – 2023 Point-in-Time Estimates by CoC (https://www.huduser.gov/portal/sites/default/files/xls/2007-2023-PIT-Counts-by-CoC.xls) https://www.huduser.gov/portal/datasets/ahar/2023-ahar-part-1-pit-estimates-of-homelessness-in-the-us.html

The 2016 Annual Homeless Assessment Report to Congress, p.1-4 https:// www.huduser.gov/portal/sites/default/files/pdf/2016-AHAR-Part-2.pdf

The Power of On-site Programming

Lotus House’s gender-specific mission is rooted in an evidence-based, research-driven focus on how to best serve their guests. The needs of families with children, youth and individual women are distinct, and Lotus House tailors its programs and services to those needs. Through its participation in various research initiatives with academic institutions such as Florida International University, Lotus House works to fine-tune its child and family therapeutic services and programming and disseminate best practices to other shelters nationwide.

Case analyses have shown that one-third of Lotus House’s guests experienced childhood abuse and roughly 99 percent have a history of intimate partner violence, domestic abuse, gender-based violence, or other major trauma. Women with such adverse life experiences can end up on the streets when they seek to escape these situations. Women experiencing homelessness struggle with the economic, psychological, and physical fallout from past victimization and then deal with physical vulnerability when trying to remain undetected in public spaces. Homeless women and youth are at great risk of human trafficking, sexual assault, and other physical violence, often from men who initially offered them protection on the streets. When women do seek help from social service organizations, they are often turned away. According to the National Network to End Domestic Violence’s (NNEDV) most recently released Annual Domestic Violence Counts Report, while 44,616 adult and child survivors of domestic violence were served by some form of housing program (including emergency shelter, transitional housing, and hotel/motel vouchers) on a single day in 2023, another 7,200 survivors’ housing needs could not be met by existing programs due to capacity issues. Even with its own expanded capacity, Lotus House must too often turn away women and families in need of safety.

Lotus House’s founders envisioned the shelter as a refuge from these past traumas. While staying there, women have the opportunity to heal past wounds and start on a path to empowerment while being cared for, treated with respect, and buoyed by an environment of shared community.

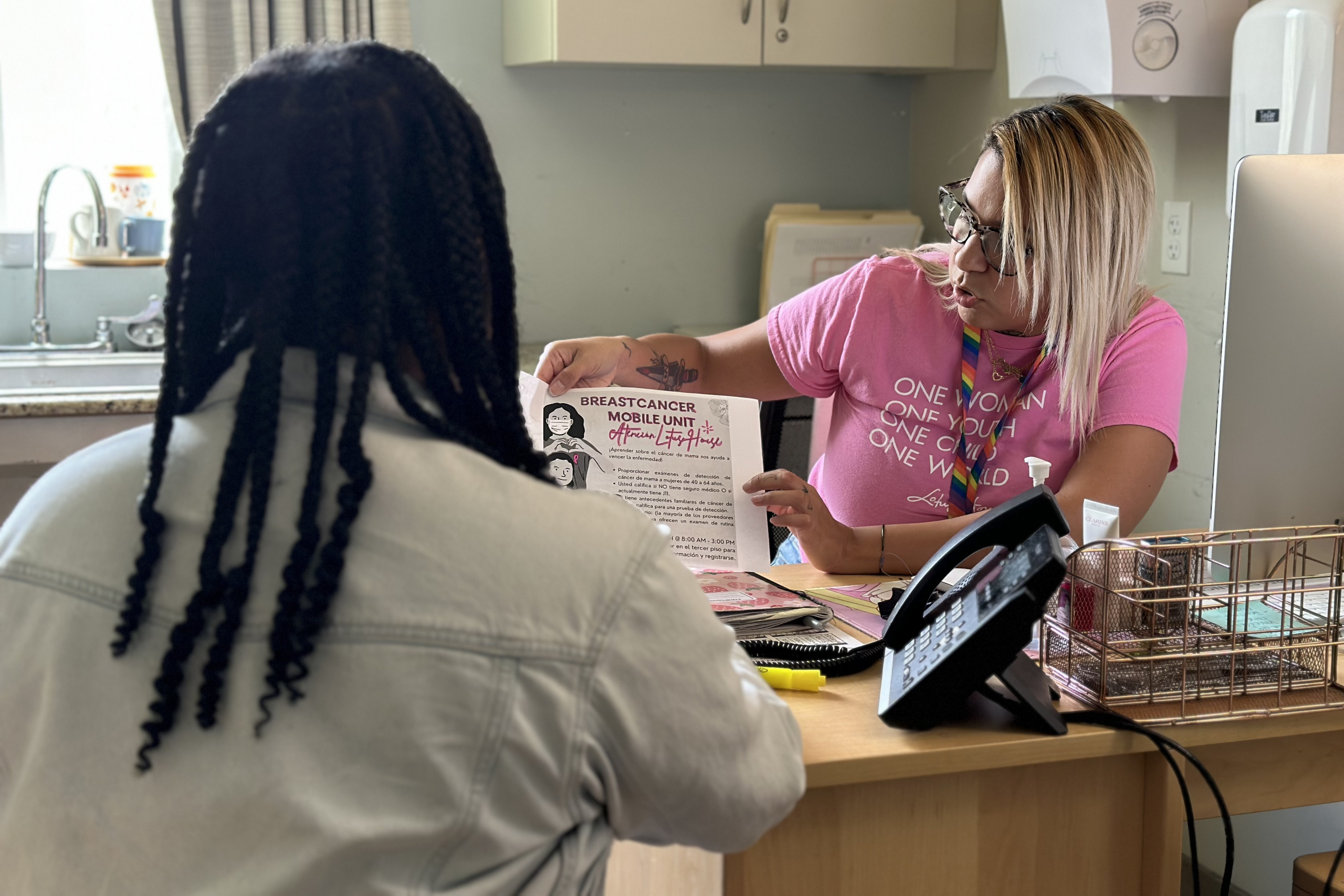

Wraparound services include linkages to medical care as well as on-site mental health screenings and treatment, including individual and group therapy and support groups. An on-site Good Samaritan health clinic, Lotus Wellness Center, was originally all volunteer-led, including trainees from the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine. Jessie Trice Community Health Center, a federally qualified health center (FQHC), then operated a neighborhood clinic at Lotus Village until last year. The shelter plans to reopen the health clinic once a new provider is identified. Improving access to health and mental health services is a primary aim of both Lotus House and the National Women’s Shelter Network.

Educational offerings for adults run the gamut from basic education and computer skills and GED preparation to life skills classes (health education, financial literacy, parenting classes) to employment training. Lotus House offers in-house internship programs related to retail (at its Lotus House Thrift Chic Boutique), culinary arts (in the David and Leila Centner Culinary Center to provide daily meals to the shelter community), hospitality (at the shelter, focusing on customer service, housekeeping, and inventory management), and hydroponic farming (the Farm services the shelter’s Culinary Center and has pumped out 49,000 pounds of fresh produce since 2019). Resource coordinators help guests access all benefits and housing specialists assist with the housing search and move-out process.

Enrichment activities include yoga, meditation, hair and nail care provided by volunteers at the Vivian Morera Healing Hands Salon, music, dance, poetry, and even a multimedia studio where the Lotus Village Voices podcast is produced.

Children have access to a wide array of programming as well. The United Way Center for Excellence in Early Education provides childcare for newborns to three year olds. School-age children benefit from homework help, play spaces, and a host of enrichment activities, including field trips. Play and positive relationship formation is at the center of it all.

A Perennially Blooming and Evolving Flower

Twenty years after Collins spotted that first three-story building, Lotus House and its affiliates are thriving and making an impact inside and outside of Miami. Since inception, over 12,000 women, youth, and children have rested their heads on a Lotus House bed, 3.5 million meals have been served, and 100,000+ counseling sessions have been held.

Lotus House shelters over 525 individuals each night. Every year an impressive 85% of guests successfully exit shelter to the next step on their journeys, however long that takes due to their own particular circumstances. In 2018 Collins told CBS Miami that, “No one heals in a rush. We’re here to make sure that all the support systems that [guests] need are in place before [they] make the move so that [their] transition will be a successful one.”

Current Lotus House Executive Director Isabella Dell’Oca took some time to reflect on the organization’s two decades of successes and answer questions from ICPH. Responses have been edited for clarity.

Q. Do most of your guests come from the communities in which you operate?

A. Yes, most of our guests come from the communities in which we operate. Lotus House is located in Overtown, one of the poorest neighborhoods in Miami, chosen specifically because of the overwhelming need for shelter, support, and resources for women and children in this underserved community and surrounding areas.

Our data reflects this focus, with 14% of our guests listing Overtown (zip code 33136) as their last place of residence before coming to Lotus House. Additionally, other nearby neighborhoods such as 33142 and 33147 represent 9% and 8% of our guests, respectively. Importantly, a significant percentage of our guests return to Overtown after exiting Lotus House, highlighting our commitment to serving and uplifting this community through tailored, impactful programs and services.

Q. How do guests find their way to you? Is the need for shelter in Miami still greater than that which you can provide?

A. Guests are referred to Lotus House from homeless outreach teams, other shelters, rehabilitation centers, prisons, courts, and hospitals, as well as directly from the streets. Lotus House is often identified as the best option for women and children with high special needs, and we are often the last and final safety net for the most fragile in our community. Guests arrive at Lotus House through a coordinated entry process. Their intake is scheduled and followed by a comprehensive assessment of their social, physical, and mental health, employment, education, and other needs by the Lotus House team. An individual action plan is developed with each guest tailored to her specific needs.

The demand for shelter beds and supportive services far exceeds availability in Miami-Dade County. Despite doubling our capacity in 2018 with the opening of Lotus Village—making Lotus House the largest women’s homeless shelter in the nation and serving over 525 women, youth, and children nightly—there is still a never-ending waitlist of referrals for women and children desperately seeking shelter.

Q. What is your average length of stay? Do you have any time limits on how long guests can stay?

A. At Lotus House, the average length of stay is currently 199 days, or just over six months. Unlike short-term shelters, Lotus House was designed to provide women, youth, and children with the time they need to heal, grow, and build a safe, secure future for themselves and their families, truly breaking the cycle of homelessness.

We are seeing longer stays due to rising housing costs, increased rent, and fewer housing vouchers being available. Rather than enforcing a time limit, we focus on providing guests with the tools and resources they need to transition to a better way of life. Even after exiting the shelter and moving into their own housing, many guests remain part of the Lotus family, returning for resources and support, to volunteer, or simply to reconnect and say hello. Lotus House continues to be a lifelong resource for our guests.

Q. What challenges are unique to families experiencing homelessness in Miami and/or Florida?

A. Families experiencing homelessness in Miami are faced with challenging circumstances driven by the region’s severe housing crisis. Reports show that rents in Miami-Dade have surged 39% between 2017 and 2022, with median costs now exceeding $2,600 for a one-bedroom apartment and $3,300 for a two-bedroom apartment. More than half of the county’s households are “cost-burdened,” spending over 30% of their income on housing alone.

Compounding the issue, wages in Miami-Dade have not kept pace with the skyrocketing costs of housing, childcare, transportation, and healthcare. The Miami-Dade Self-Sufficiency Standard shows that a single parent with one preschooler and one school-age child would need to earn $44.23 per hour—or work an impossible 149.7 hours per week at minimum wage—to meet their family’s basic needs. Many families are one emergency away from homelessness.

Q. What’s the history of your Alumni leadership efforts in staffing and through the Alumni Advisory Board—why is this approach so important to your agency?

A. From the very beginning, Lotus House has recognized the invaluable contribution of alumni in shaping and supporting our programs. We saw an opportunity to address staffing needs by hiring alumni who were looking for employment. Our staff demographic reflects those we serve, and alumni now make up approximately 40% of our team. They bring unique insights, empathy, and relatability to the program and are role models for current guests—tangible proof that the program works. In addition to staffing, our Alumni Advisory Board allows program graduates to play an active role in shaping the direction and strategy of Lotus House. Their input ensures that our services remain relevant, effective, and responsive to the real needs of our community.

Q. The forthcoming Children’s Village looks like the organic outgrowth of partnerships with many community-based organizations. How has Lotus House’s relationship with the wider community evolved over the years?

A. We know it takes a village! From the beginning, we’ve understood the importance of collaboration in providing comprehensive care to our guests. Our holistic approach means working closely with community-based organizations in key areas such as health, mental health, education, employment, childcare, and more. By recognizing our own strengths and the expertise of others, we’ve been able to offer our guests the best possible support as they work to improve the quality of their lives on every level, achieve greater self-sufficiency and transition to permanent homes off the streets.

As we’ve grown, so have our partnerships. We’ve strengthened our ties with local organizations and expanded our network to ensure a multi-faceted approach to service delivery. These collaborations have been integral to our success, and as we look ahead to the forthcoming Children’s Village, it is clear that these partnerships will continue to strengthen our community.

Beyond serving our sheltered guests, Lotus House has consistently supported the residents of our Overtown neighborhood, standing as a beacon of hope and a reliable resource for those in need. Our ability to work hand-in-hand with our neighbors and partners has allowed us to foster a strong sense of community and to ensure that the solutions we offer are informed by those we serve.

Q. What has changed about how you’ve served women/children/families over the last 20 years? What has stayed constant?

A. From the very beginning, Lotus House was designed as a prototype shelter and resource center to address the unique, gender-specific needs of homeless women in a holistic and innovative format. Recognizing that many women arrive with children, we ensured our approach addressed their specific needs as well.

What has changed is our growth and refinement. Over the years, we expanded our capacity and programming while staying true to our gender-specific framework. Extensive research and staff training enabled us to adopt evidence-based counseling modalities, providing deeper insights into the needs of homeless women, youth, and children. This has allowed us to better support policy and advocacy efforts at the national level, such as our initiative to establish the National Women’s Shelter Network, fostering greater awareness, social inclusion, and resources for those we serve.

Throughout the years, we have remained steadfast in our dedication to addressing the unique challenges faced by women, youth, and children experiencing homelessness and providing a dignified, trauma-informed, gender-responsive environment where they can heal, learn, grow, and blossom into who they are truly meant to be.

Note: Citations and sources for data are included in the PDF version of this document available by clicking Downloads below the Table of Contents.

Allie’s Place Family Residence: A Multi-Service Family Shelter Making Strides in the Bronx

By Derrick Holman

At the far end of a long, quiet block in the Bronx, New York, nestled between one of the borough’s largest public parks and a vast public housing development, stands a tall maroon and grey brick building with large glass windows, modern steel accents, and a small but well-manicured front lawn. Three ten-foot-tall white vertical banners drape from the exterior of the building emblazoned with the words “Allie’s Place” next to a small, heart shaped logo patterned in blue. A flagpole stands in front of the building and a few newly planted trees and shrubs pepper the streetscape. To unwitting passersby, the structure might appear to be an elementary school, a community college dorm, or even a small science center. In reality, Allie’s Place Family Residence stands as a vital resource in the heart of a challenged but resilient community, providing shelter and support to nearly one hundred families in need. The building’s exterior, with its simple yet welcoming façade, reflects the stability and warmth offered inside. Its sturdy brick walls create a haven, where families can find respite to rebuild their lives. As a cornerstone of support, Allie’s Place offers more than just a bed and a roof over one’s head—it is a place where families can heal, grow, and start anew.

An Approach With a Track Record

Homes for the Homeless (HFH) is a New York City-based shelter operator and social services provider with a nearly 40-year track record operating facilities that serve both homeless families and their surrounding communities with secure temporary housing, community-based employment training, and high-quality, educational programming.

On any given night, HFH serves approximately 720 families experiencing homelessness, including nearly 780 children and teens, at facilities in the Bronx, Queens, Manhattan, and Staten Island. The organization’s signature approach to supporting families who are experiencing homelessness combines the basic services of traditional shelters with a full range of educational and employment programs designed to help lift families out of poverty and provide a reliable path to permanent housing. Rather than waiting until families obtain stable housing to provide them with key resources, HFH ensures that a family’s brighter future begins the minute they walk through the doors.

A True Community Resource: Serving Residents and Giving Back to the Local Community

As both a shelter operator and social services provider, HFH champions a transformational model of serving homeless families and their surrounding communities that provides safe, temporary shelter while simultaneously addressing the underlying causes of family homelessness: poverty, domestic violence, family trauma, incomplete education, mental health and addiction, and a lack of job skills or job history, among other factors.

The HFH model, come to life in Allie’s Place, builds on the foundation of the traditional shelter, meeting the short-term basic needs as well as the long-term developmental needs of the children and adults staying in their facilities. These needs include safe housing, childcare, food access, nutrition, education, recreation, employment, and health care.

Simultaneously, this signature approach adds resources to the citizens of the surrounding neighborhoods.

Some have criticized service-rich and aesthetically pleasing shelters as discouraging people to move out, a notion that HFH Deputy Executive Director Gretchen Hernandez disagrees with, noting, “People stay in shelter for various reasons, but it’s not because it’s nice, it’s clean, and we give so many services.”

Two things can be true at the same time. She believes that people want to leave shelter, be independent, and have their own home but that they also deserve a welcoming environment and the help they need to get back on their feet.

“My hope is for clients to be able to work with our staff to determine what they need and for staff to work with the clients to make sure they have the resources to achieve those goals, no matter what those goals are,” Hernandez adds.

Allie’s Place Family Residence Opens at Height of Pandemic

In March 2020, as the world started to shut its doors, HFH opened its first newly constructed, from-the-ground-up facility, the culmination of years of lessons learned at its shelters across NYC. Since then, Allie’s Place serves up to 99 families at a time in the Soundview neighborhood of the Bronx, New York. Families residing at the facility are composed of a single parent or guardian with a single child or, in some cases, a pregnant mother who is expecting a child. While the shelter serves families with children up to 18 years of age, the majority of families are typically comprised of a single parent with a single child between the ages of 0 and 10 years old.

Many of the Allie’s Place clients are survivors of domestic violence, gender-based violence, or other forms of physical trauma and abuse. Other residents have experienced displacement due to eviction, overcrowding, job loss, or hazardous housing conditions, including those impacted by fires or natural disasters. Others struggle with physical or mental health concerns or addiction, while yet others have been impacted by any one or more of the aforementioned conditions, whether personally or indirectly.

While at Allie’s Place the staff support families with traditional social services like case management and health referrals plus a full range of auxiliary programs designed to meet the specific needs of children and their families.

Families assigned to Allie’s Place stay in private studio-like units with a kitchen and bathroom; receive on-site case management; and are able to participate in comprehensive support services during their time in the shelter including re-housing support, employment support, and on-site substance treatment and mental health services through a partnership with Camelot Counseling. On any given night nearly 200 individuals are staying in one of the 99 rooms at Allie’s Place Family Residence, including around one hundred children.

Charima Thompson is the Director of Family Services at Allie’s Place. In her role, Charima oversees a department of case managers, housing specialists, and client care coordinators who work collaboratively across each of the shelter’s departments and with the New York City Department of Homeless Services (DHS) to provide these support services for the shelter’s clients.

As a product of the foster care system herself, Charima takes her role seriously and deeply understands the challenges many of her clients experience on their path to financial stability and permanent housing.

“A lot of them don’t have family [outside of the shelter],” she notes. “They come here alone and when they leave, they’re still alone. So, while we’re here to assist them, we make sure we instill independence in them, so they understand ‘it starts with you, and it ends with you.’”

Julissa Lantigua, a Senior Administrator at HFH who directly oversees Allie’s Place and supports several other sites in the HFH network, echoes that sentiment.

“A lot of times clients in shelter lack community or family support so we become their support system,” says Lantigua. “They may not know the milestones their children should be reaching [by a certain age] or the benefits they’re entitled to or how to access supplemental resources. We provide that information and help them in many different areas beyond just housing.”

Both Thompson and Lantigua have grown within the agency during their tenure, having held various roles across multiple HFH sites. Providing career advancement and encouraging staff longevity is a goal that the organization is working hard to achieve.

In describing the impact Allie’s Place has on its clients, each of them highlights not only the importance of providing high quality services, but the essential interplay between the provision of those services and the physical and communal environment that the facility provides to its clients, which, combined, enable the site to meet and often exceed its goals in educating, employing, and re-housing its residents.

Site and Services

The facility at Allie’s Place is a newly constructed five-story building with three residential floors and two floors of programming space, including a pre-school, afterschool, daycare, and 3,200 sq. ft. culinary job training center. The facility also includes outdoor recreational space, an on-site culinary garden, youth and adult classroom space, and shared meeting spaces for both internal and community use.

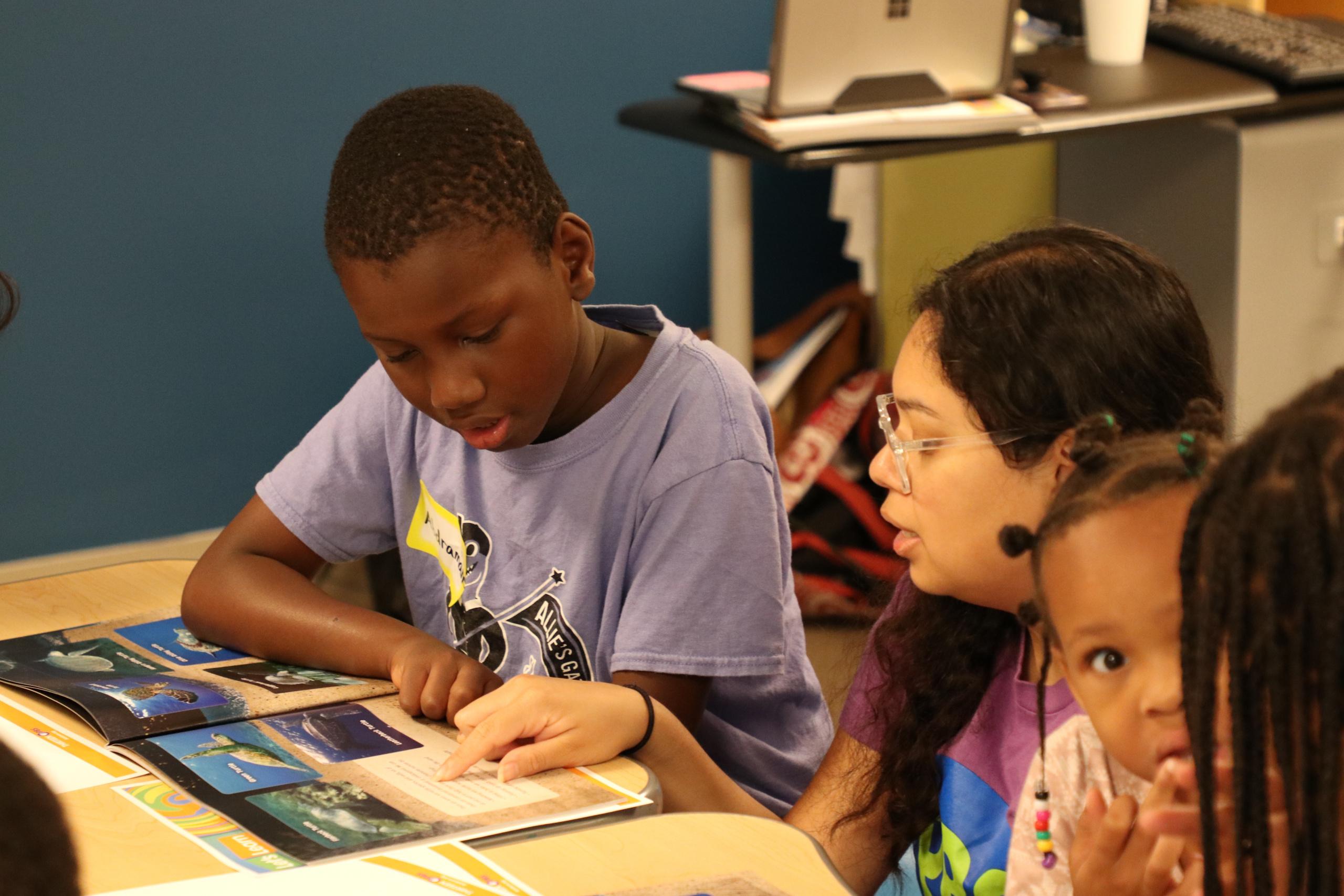

The on-site afterschool enrichment program is offered to school-aged children of families residing in the facility while the on-site pre-school serves three and four year olds from the site and the community. The cornerstone of the site is Allie’s Place Center for Culinary Education & Employment, a unique culinary job training program that is open to shelter residents and the surrounding community alike.

The afterschool program at Allie’s Place serves up to 40 children at a time and provides shelter parents with crucial respite from the constant demands of parenting, giving each parent the time and opportunity to take care of private or personal matters, whether that be housing paperwork, a job search, laundry, or self-care, while their children can safely make new friends and enjoy enriching programming ranging from homework help to sports activities to youth leadership opportunities and more.

The Culinary Center, on the other hand, serves as a resource to the whole community, including local employers and various community-based organizations, thereby supporting the shelter’s role as a multi-service resource center promoting adult education, job training, employment assistance, and workforce development.

Programming across both departments as well as for the on-site pre-school and daycare is supported by a central partnerships team that serves all six HFH sites from a central office in Manhattan. The partnerships team coordinates with staff at each site—including Allie’s Place—to facilitate supplementary programming, donations, volunteer activities, holiday and cultural events, youth field trips, a summer sleepaway camp, and more.

Annamaria Santoro, Senior Director of Operations at HFH who oversees the partnerships team, among many other responsibilities, highlights the “self-fulfilling prophecy” that a positive and supportive environment like Allie’s Place can have on clients of the shelter.

“When you walk into Allie’s Place, it doesn’t feel institutional,” Santoro says. “For people who don’t have experience with shelters, they may have a negative perception of what a shelter is, but Allie’s Place is NOT that. It honestly feels more like a dorm in a college than a shelter, which makes people feel good, which makes them want to work harder to get back on their feet, which helps them move out faster,” she continues. “It gives people the opportunity to be the best version of themselves.”

Tierra Gunther, Partnerships Manager at HFH, adds that collaboration with the on-site staff and ongoing family engagement is essential to serving families and helping kids feel like they can communicate their wants and needs, whether in the facility, in school, in their home life, or beyond.

“The demographics of the site and ages [of children at the site] are always changing,” Gunther says, “which requires constant communication between our team and the site staff to understand the needs of the kids and the needs of the site.”

The central office at HFH has departments dedicated to operations, buildings and facilities, communications, finance, compliance, procurement, programs, partnerships, policy, and infrastructure and technology (IT), all of whom work together with each site to provide executive and administrative leadership and support. Collaboration between the central office and on-site staff is key to each shelter’s success.

Allie’s Place employs approximately 70 full-time site staff comprised of security, maintenance, case management, employment, re-housing, daycare, recreation, afterschool, culinary arts, and administrative staff, with the practice of drawing on qualified talent from within the local community during hiring.

Lantigua, who leads all of Allie’s Place staff, highlights the importance of teamwork and cross-department collaboration. “I have a great team of people who are committed to the mission and a great set of team members in every department; everyone wants to make a difference, and everyone’s role affects the families; the core of our work is social services but there’s a lot more to a building than just the services. Housekeeping and maintenance are just as important in creating a great facility as family services.”

That said, the programs at Allie’s Place, including the site’s internal afterschool & recreation program, play a major role in helping residents and clients of every age succeed.

Allie’s Place Afterschool & Recreation

The purpose of Allie’s Place afterschool & recreation program is to extend academic learning beyond each child’s school day, to nurture each child’s physical health, and to provide a safe, structured environment for children to make friends and play with other kids while in shelter. The program is designed to instill self-confidence in all children and to provide foundational learning experiences that nurture each participant’s mind, body, and spirit.

Allie’s Place’s Director of Afterschool & Recreation, David Belmar, who has been with the agency for nearly five years across two different sites, highlights the importance of creating a space for “kids to be kids,” whether through academics, cultural programming, or events. When asked what makes his program successful and how he defines success, he insists that you can gauge the success of a program by how much community is being built within the facility and beyond it. “At Allie’s Place,” he says, “you see kids teaching other kids; you overhear families checking up on each other and sharing advice and resources. Many clients stay friends even after moving out of the facility.”

This, he says—the genuine connections between families and their children and the idea that “we’re all in this together”—defines his and his program’s success.

Through its thematic programming, the afterschool department at Allie’s Place provides an environment that creates this sense of belonging, builds academic confidence, and helps foster new friendships and interests, while promoting respect for all cultures, values, and beliefs. For a program that operates in a challenging neighborhood and serves clients from dozens of constantly changing ethnic, racial, social, cultural, and linguistic backgrounds, this feature is extremely important in creating a safe and accepting environment. It all begins, according to David Belmar, with “treating each individual like an individual.”

Youth Education And Recreation

A typical afterschool session at Allie’s Place starts with coloring, board games, or time to enjoy a healthy snack. Once the children settle in, there is homework time, an educational activity, and a family-style dinner. Common activities include dance classes with an instructor who also specializes in social and emotional learning; digital photography classes with professional photographers; hands-on STEM lessons; and family movie nights for children and parents to make and share positive memories.

Even still, says David Belmar, “sometimes the greatest teachers in life are everyday people and everyday experiences.” For the children and parents at Allie’s Place, that can mean learning from and through each other.

The children in the afterschool take pride and ownership in their group: naming and designing their own mascot, the Allie’s Gator, participating in educational field trips, and even making suggestions for new programming based on their shared interests. Parents often refer to the program as a “lifesaver” that gives them the flexibility to handle other responsibilities with the comfort of knowing their child is safe, both physically and emotionally.

According to Belmar, academically and socially enriching children in this way during their time in the shelter is extremely important for each child’s personal development and for ensuring each family’s ability to successfully transition their child out of shelter and into potentially new neighborhoods, schools, and social environments when they leave.

While the stress related to homelessness can be taxing for any person, children are especially vulnerable and can be susceptible to increased anxiety related to displacement, bullying, and/or depression. Providing supplementary education and age-appropriate recreation in a fun, safe, and enriching environment is essential to maintaining a child’s energy and spirits. Equally important, however, is ensuring the adults in a child’s life are prepared for the responsibilities of parenthood and equipped with the skills to provide for their child.

Allie’s Place Center for Culinary Education & Employment

In it’s fifth year of operation, Allie’s Place Center for Culinary Education & Employment was designed to teach adult students the foundational skills necessary to obtain employment in the culinary and hospitality fields or to pursue an advanced education in the culinary arts.

Participants who complete culinary coursework at Allie’s Place are empowered to pursue entry-level employment in a full range of culinary settings, including restaurants, cafés, cafeterias, and commercial kitchens, as well as in hotels, catering companies, healthcare facilities, and chain restaurants, depending on their strengths and desired specialties. Students are also encouraged to apply to local culinary schools or internships programs where they may earn advanced certifications or complete advanced coursework.

The scope of the Center’s culinary program includes basic culinary arts training; baking and pastry arts training; barista training; front- and back-of-house training; and job readiness support. All participants are supported in their search for employment and are provided the opportunity to earn the New York City Food Protection Certification at no cost, which enables them to work in food service settings throughout the five boroughs.

Promising participants can even be offered the opportunity to intern at the Center itself following graduation from the program, providing these interns the opportunity to supplement their own culinary education while supporting new incoming students.

As Director of Culinary Education Gabriel Rodriguez often states, “food is universal” and the opportunities available to those with meaningful culinary skills are vast. But it doesn’t stop there. “There’s a lot of attributes that we teach that can be applied to any industry, including time management, professionalism, communication—both verbal and nonverbal—and managing stress. What we’re teaching them is not just preparing them to be a line cook or a chef. If they don’t end up in the [culinary] industry, the things we’ve taught them would apply to any industry.”

Outreach efforts to recruit program participants from the local community take place online and in-person at surrounding public housing complexes, neighborhood-based organizations, houses of worship, job training centers, and local community events. The Center also partners with local industry organizations and non-profits to provide its students with opportunities including restaurant tours, chef seminars, and local field trips.

Since its launch in March of 2020, over 350 students have graduated from programs at Allie’s Place Center for Culinary Education & Employment. In this time, the Center has expanded and refined its programming, as its instructors and staff continually work to optimize the curriculum to provide participants with the greatest opportunity to earn meaningful employment with livable wages and benefits.

“We want to make sure we are sending students into the workforce with employers who will be good to them,” says Rodriguez.

Whether participants of the program are residents of the shelter or of the surrounding community, the curriculum is structured to provide all participants with greater freedom and flexibility in consideration of the unique challenges that those living in shelter often face when it comes to obtaining education or job training. For example, training courses at Allie’s Place are offered in short, week-long intensive sessions that can be taken independently or consecutively, rather than as multi-weeks-long commitments that most similar programs require of their students. This level of flexibility in scheduling allows shelter residents who may have more difficulty finding accessible childcare the opportunity to receive the same degree of training as non-shelter-based programs on a more shelter-friendly schedule.

A number of the Center’s graduates have gone to find employment in culinary settings through referrals from dedicated employment specialists, including at local employers like the Bronx Zoo, New York Botanical Gardens, LaGuardia Airport, and Citi Field. Other graduates have earned coveted positions within the Department of Education, working in full-time food service roles at local public or charter schools. Roles such as these in more institutional culinary settings can often provide older graduates and working parents with greater stability, favorable working hours, and a better work-life balance. Yet other graduates have found enjoyable work in more traditional cafes, restaurants, diners, and specialty food settings like The Donut Pub and Funny Faces Bakery.

The Center’s Lead Culinary Instructor Gregorio Pedroza knows a thing or two about funny faces. As a former stand-up comedian and fifteen-year veteran of the culinary industry, Gregorio peppers each of his classes with a healthy heap of self-proclaimed dad jokes and one-liners—as well as more serious culinary techniques and terminology. Chef Greg, as he is affectionately known, lives by the mantra “a laughing brain is the most absorbent.”

Greg firmly believes that helping students loosen up and feel comfortable in the kitchen through humor is an essential component of his job and interactions, because “if they feel safe, they can learn.”

For a program and facility serving a community that includes many survivors of trauma, domestic violence, systemic poverty, and countless other traumatic experiences, this couldn’t ring truer.

An Engaged Member of the Community

As a temporary housing shelter and community resource, Allie’s Place Family Residence strives to be an engaged member of the community, providing services, opportunities, information, and resources for its temporary residents as well as its neighbors and partners in its surrounding areas. Much like a community school or recreation center, Allie’s Place serves as a hub for bringing families together while creating a safe, welcoming community for all to thrive.

For those residing at Allie’s Place, it is a place of peace, refuge and opportunity. For those working at the facility, it is an opportunity to help others, to give back, and to make an impact. For the surrounding community, it is a much-needed economic, social, and communal resource that provides far more than just a place to stay for those in need.

The primary goal at Allie’s Place is to help residents transition into—or back into—permanent housing and to improve the overall quality of life for all those who walk through its doors, from residents to students to neighbors to staff. Providing effective shelter and comprehensive support services in this way requires a highly coordinated and intentional investment in physical space, a compassionate staff, strategic programming, and ongoing community engagement, but the result is a far more effective and nurturing means of achieving its overarching goal, which has the net benefit of transitioning those living in shelter into a home and a life that is better for their families, their community, the city, and themselves.

Note: Citations and sources for data are included in the PDF version of this document available by clicking Downloads below the Table of Contents.

A Mission and a Model in Atlanta

Snapshot

From a soup kitchen founded in 1938 at the height of the Great Depression, Atlanta Mission has expanded to serve the broader needs of individuals and families experiencing modern day homelessness in the metro-Atlanta region. With the overall city poverty rate at 18% and child poverty rate of 27% in 2023, the organization provides critical services to Atlantans in need.

Its service model includes multiple stages:

- Emergency services

- Provides basic needs, including shelter, meals, showers, and laundry facilities—a level of stability that creates space to build relationships and trust with staff

- Two-phase residential services:

- Phase 1: Exploration of underlying causes of clients’ homelessness and creation of plan to address them

- Phase 2: Holistic programming to address individual needs

- Transitional housing upon completion of residential services

- Secured housing after program completion

Its Transformational Model focuses on structured, multiphase support with the goal of clients gaining security, stability, and lasting independence and the understanding that true transformation takes time, patience, and compassion.

Additional Support Services include food, shelter, critical needs assistance, addiction recovery programs, job attainment, and career counseling. Alumni services offer support in job retention and housing assistance as clients transition to permanent housing.

By the Numbers (2024)

Note: Citations and sources for data are included in the PDF version of this document available by clicking Downloads below the Table of Contents.