One in six English Language Learners (ELLs) in New York City public schools is homeless. While learning science, math, and social studies, these students face the added challenge of learning the English language.

Adding to the instability of homelessness, it is common for homeless students to transfer schools mid-year; 22,188 homeless students transferred mid-year in school year 2015–16. While they have the right to remain in the school they attended when they became homeless, many of these young students transfer schools to be closer to their shelter or other temporary housing situation. Every school transfer is estimated to set a student back academically by up to six months—a loss of learning for any student, but for ELLs a particularly challenging obstacle.

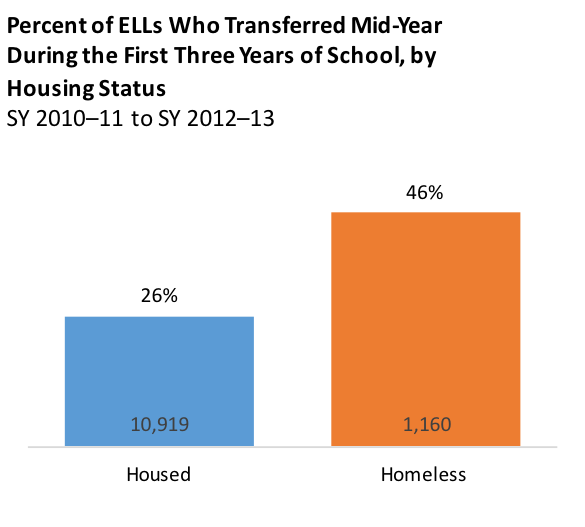

When homeless ELL students transfer schools mid-year, which they are nearly twice as likely as their housed peers to do (46% to 26%), they not only move schools but often switch between types of ELL programs, as well. Many of these students will have to adapt to a new style of instruction depending on the services their new school offers. For example, they may move from a bilingual program to a pull-out “English as a New Language” (ENL) class. According to Education Trust New York Deputy Director Abja Midha, “[if] the student has to make the switch from bilingual to ENL, that’s going to have an impact if a student is used to one mode of instruction and then all of a sudden is going to an all-English environment.”

Families can request to transfer to a school with a bilingual program within the same district as the new school, but Advocates for Children Immigrant Students’ Rights Project Director Rita Rodriguez-Engberg points out, “If there are no available seats in bilingual programs in the child’s district, the students may not have the chance to attend one of those programs.” Fortunately, the New York City Department of Education (DOE) continues to expand its bilingual program offerings, increasing the likelihood that an ELL student can move from one bilingual program to another if he or she must transfer schools. Another source of instability for homeless ELL students who transfer mid-year is a possible lag between when a student arrives at their new school and when they are placed in an ELL program. Clear communication and data-sharing between schools can help prevent lags in services after a student transfers. Since 2011, the State has mandated data collection and quarterly reporting on ELL students by the DOE. Even though progress on data collection is being made, work is still left to be done. An official communication procedure between homeless liaisons and schools that homeless ELLs transfer from would ensure the prompt transmission of a students’ records and services.

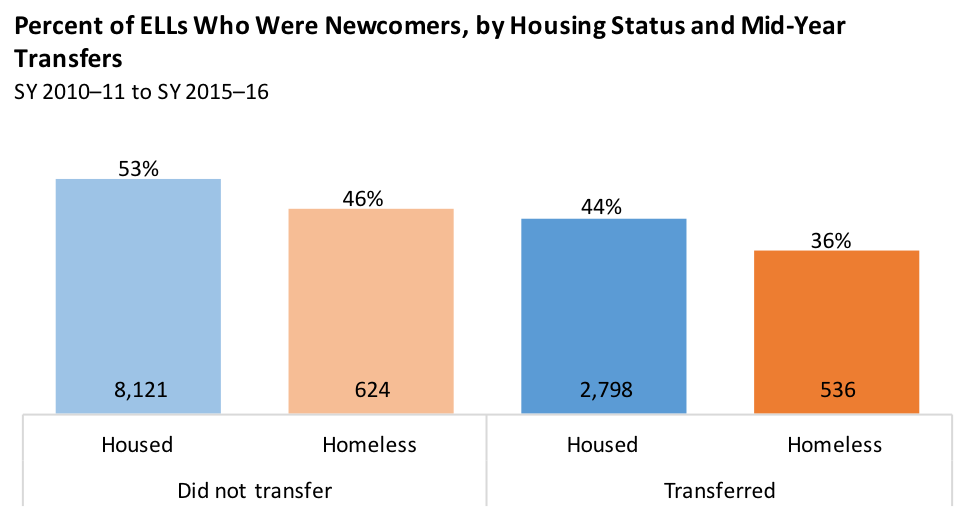

Transferring schools mid-year increases the likelihood that homeless ELL students will take longer to learn English. Of homeless ELLs who do not transfer schools mid-year, almost half (46%) learn English within three years. But among those who transfer in their first three years of school, only one third (36%) become fluent in English within three years.

This timing is key—those homeless ELL students who become fluent within the first three years of their education perform as well or better than their non-ELL peers. Providing supports and consistent services to homeless ELL students, especially the 46% who transfer school mid-year, ensures the academic resilience of this vulnerable population.