April 2018

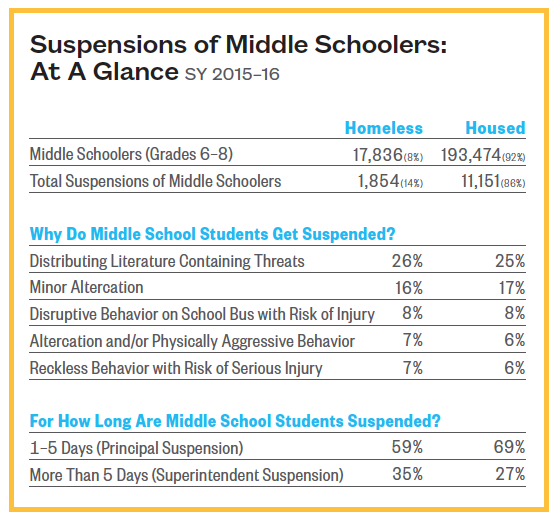

In New York City, there are 102 suspension hub middle schools where students are disciplined at extremely high rates. In suspension hubs, 1 in 7 homeless students (14%) were suspended—compared to 1 in 25 middle school students overall (4%).

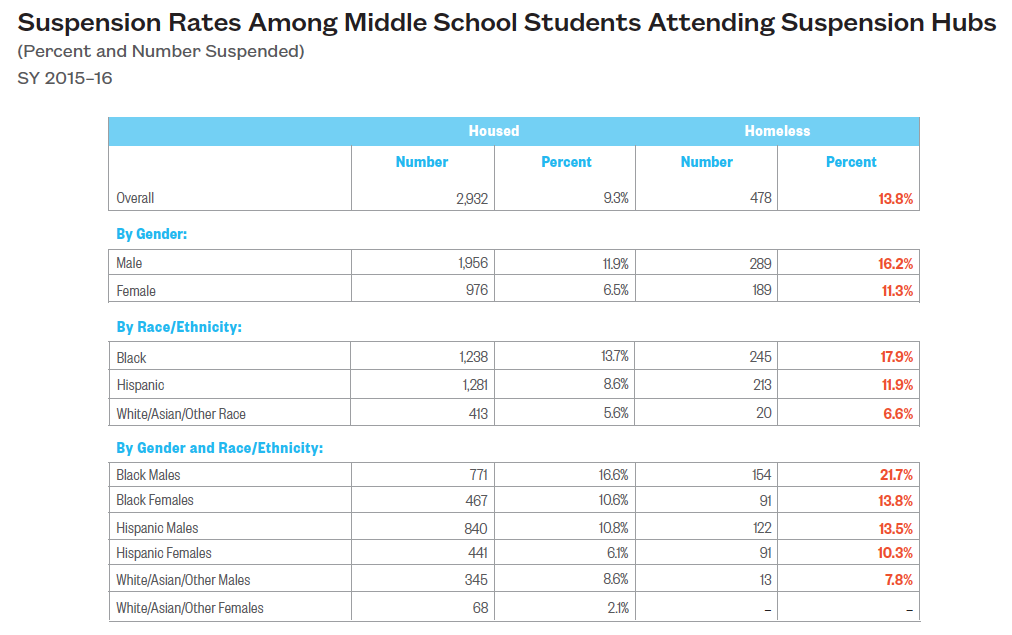

Low-income students and students of color are disproportionately impacted by school discipline. In suspension hubs, 1 in 5 homeless black male students (22%) received a suspension, almost three times the rate of homeless white or Asian males (8%).

With roughly 100,000 homeless children enrolled in New York City public schools, it is imperative to understand how discipline policies and practices affect this growing population.

During the 2015–16 school year (SY), homeless students experienced a suspension rate five times that of their non-low-income classmates. Out of 37,500 suspensions given in New York City Public Schools, 12% were given to homeless students. With these students representing only 9% of the population, the rate at which homeless students are suspended shows a clear disparity. Homeless students already miss an average of 20 school days per year, and those who were suspended missed an additional nine days of instruction—adding up to almost six weeks of missed school or 16% of the entire school year.

The impact of suspensions on students’ academic trajectories can be serious. Six years of data reveal that 4 in 10 homeless students who are suspended will likely drop out at some point—compared to less than 1 in 10 New York City students who were not suspended.1 This does not just harm the student but costs New York taxpayers as well. Suspensions of homeless students in the class of 2015 alone could cost taxpayers an estimated $16 million or more—a cost that New York City will continue to pay each year until reforms target homeless students.2

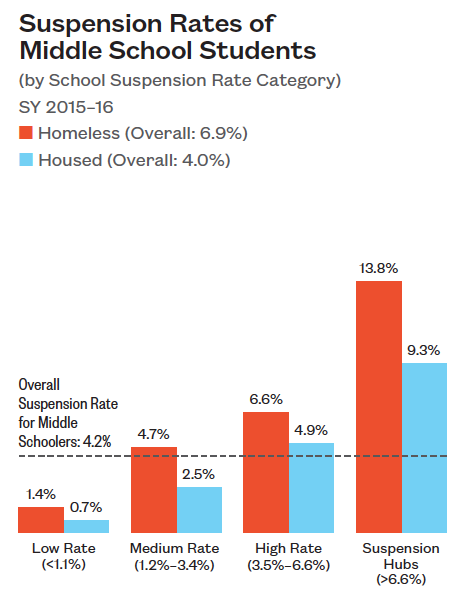

In New York City, middle schoolers see the greatest disparity of any age group in suspensions between students who are homeless and housed (6.9% vs. 4.0%). This is problematic, considering that a student’s middle school experience can either break or bolster their learning in later years. A history of being suspended in middle school can cause a student to become further disengaged in the schooling process, which can lead to a downward spiral of chronic misbehavior and low academic performance, ultimately resulting in dropping out.

Further compounding these challenges, homeless middle schoolers are more likely to attend schools with the highest suspension rates—dubbed suspension hubs—than housed students.

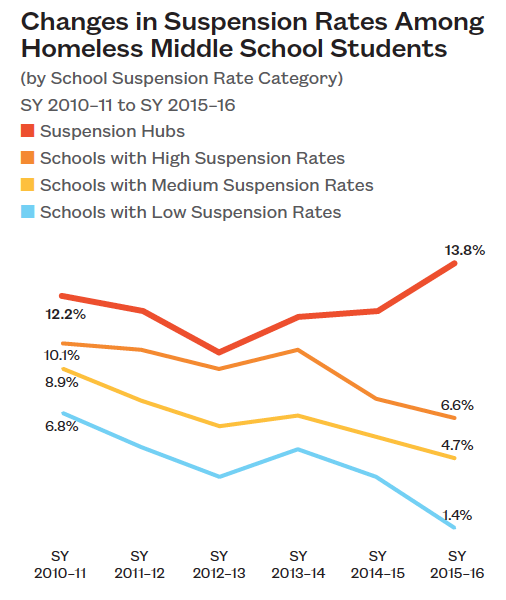

Overall, New York City schools have made significant strides in reducing suspensions while encouraging districts to adopt positive alternatives to punitive practices. Compared to SY 2010–11, suspension rates for homeless middle schoolers declined by 35 to 80 percent by SY 2015-16. However, suspension rates for homeless students in suspension hubs have actually increased by 13 percent over the same period.

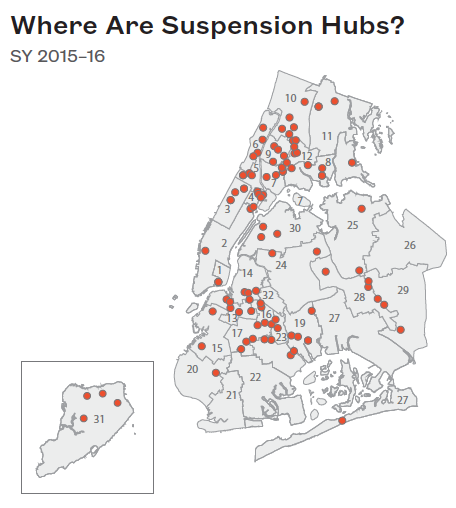

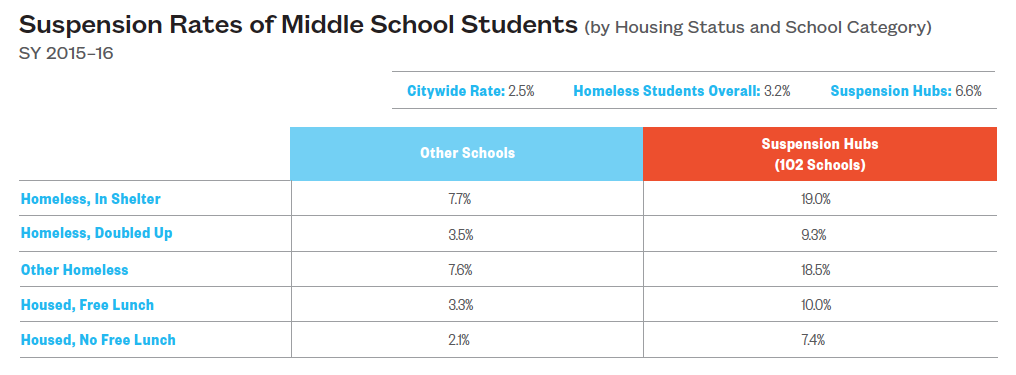

Suspension Hubs are schools that suspended more than 6.6% of students overall during SY 2015–16. This was twice the citywide rate for homeless students (3.2%) and nearly three times the rate for all students (2.5%). One in 10 New York City public school students (10%) attended suspension hubs in SY 2015–16. This rate was 1 in 5 for middle school homeless students (19%).

Key Findings

- Homeless students already miss an average of 20 school days due to absences, and the typical student who is suspended misses an additional nine days. This adds up to almost six weeks of missed instruction or 16% of the school year missed.

- Students experiencing homelessness were suspended at higher rates than their housed peers during SY 2015–16 with the greatest disparity occurring in middle school (6.9% vs. 4.0%).

- 1 in 5 students experiencing homelessness (19%) in middle school attended a suspension hub compared to 1 in 6 housed students (16%).

- Among middle schoolers, homeless students in suspension hubs were twice as likely to be suspended than homeless students overall (13.8% and 6.9%).

- The higher risks of suspension were generally among homeless students residing in shelters, homeless males, and homeless black students in middle school. In suspension hubs, 1 in 5 black males (21.7%) and students living in shelter (19%) were suspended.

- Students who go to school in the south and west Bronx, upper Manhattan, and central Brooklyn are the most at risk of attending suspension hubs. Districts 8, 10, and 12 in the Bronx each had six suspension hubs serving middle school students.

- One in three suspensions to homeless middle school students (35%) were Superintendent suspensions, lasting for at least a week of school, compared to 1 in 4 suspensions to housed students (27%). Despite committing similar infractions, homeless students received more severe suspensions.

See schools at https://www.icph.org/SuspensionHubsMap

Note: Data for the brief were provided by the New York City Department of Education. Unless otherwise noted, the source is the New York City Department of Education, unpublished data tabulated by the Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness, SY 2015–16. Cells showing fewer than 10 students were redacted.

Homeless Students Receive More Suspensions

- Across all grade levels, homeless students faced higher risks of school suspensions than their stably housed peers.

- Regardless of the school’s overall suspension rate, homeless students in middle school were suspended at higher rates than their housed classmates.

- Suspension rates in hubs increased over the last six years (12.2% to 13.8%), while rates in other schools declined by 35 to 80 percent over that same period.

“Students who are suspended are

much more likely to drop out of school

and enter the criminal justice system.”

—Evan Stone, Co-Founder and

Co-CEO of Educators for Excellence

Homeless Middle School Students Suspended at Disproportionate Rates

- Middle schools had the largest disparity in school suspensions, with the suspension rate for homeless middle schoolers over 70 percent higher than for housed students (6.9% and 4.0%).

- Homeless middle school students in suspension hubs were three times more likely to be suspended than homeless students overall (13.8% to 4.2%).

- In the 102 suspension hubs, homeless middle school students faced a far higher risk of suspension than their housed peers did (13.8% vs. 9.3%). Citywide, one-third of homeless students (35%) received a suspension of at least five days—a week of missed instruction.

Disparity in Suspensions Greater Along Racial and Gender Lines

- Homeless students were suspended at far higher rates than housed students in suspension hubs (13.8% vs. 9.3%).

- Homeless male students attending suspension hubs were more at risk than their female classmates of receiving a suspension (16.2% to 11.3%).

- Overall, black and Hispanic students are overrepresented among those suspended. However, the disparity is more profound in suspension hubs with black (17.9%) and Hispanic homeless students (11.9%) suspended at two and three times the rate than that of other homeless students. In comparison, their housed counterparts were suspended at just two-thirds the rate (13.7% and 8.6%).

- Hispanic females saw a large disparity in suspension rates between those who were homeless and housed (10.3% vs. 6.1%).

1 in 7 homeless middle school students attending

Suspension Hubs received a suspension compared to

1 in 10 middle schoolers overall.

Students Residing in Shelters Most at Risk of Suspension

- Across NYC public schools, students living in shelters faced higher risks of being suspended than their housed or doubled-up peers.

- Homeless middle school students not only face higher risks of attending a suspension hub, where rates exceed 6.6%, but are more likely to be suspended in these schools (13.8%).

- Homeless middle school students in suspension hubs who lived in shelters (19.0%) and other temporary housing (18.5%) were more than seven times as likely to be suspended as the citywide rate (2.5%).

- Compared to housed, non-low-income students who attended suspension hubs (7.4%), homeless middle school sheltered students were still twice as likely to be suspended.

School suspension is a form of discipline that rarely accomplishes the goals of correcting student behavior and encouraging school engagement. Homeless students arrive at school with emotional, psychological, and often physical trauma brought on by a combination of housing instability, economic struggles, and family turmoil. For all students and middle schoolers in particular, a school suspension places them on a path to disengagement and negatively affects their academic performance and wage-earning potential.

The most effective response to behavior issues, particularly at Suspension Hub schools, requires that school administrators, principals, and teachers engage in more than exclusionary discipline. Restorative justice practices—in which students are held accountable for behavior while remaining a part of the classroom environment—could help to further engage homeless students in their education as well as allow them to feel welcome as a member of the school’s community. The 13 percent increase in suspension rates of homeless students at Suspension Hub schools should serve as a wake-up call to administrators, particularly at a time when suspension rates are declining in most other schools. Without meaningful action from schools and shelters alike, suspended homeless students are likely to perform poorly in school and possibly drop out. This is a cost that the NYC Department of Education cannot afford and that homeless students should not have to pay.