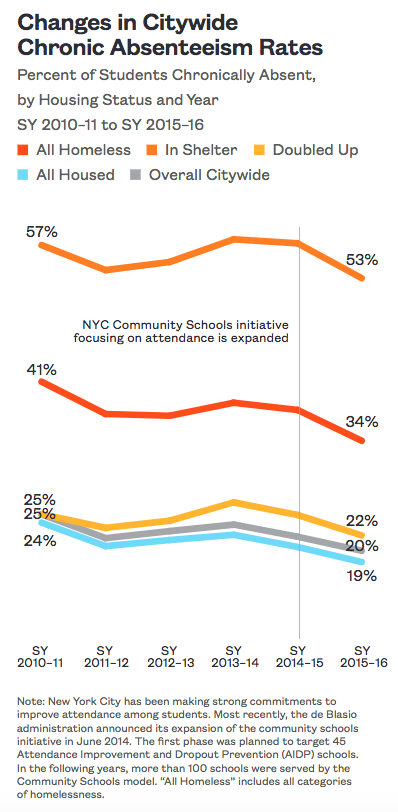

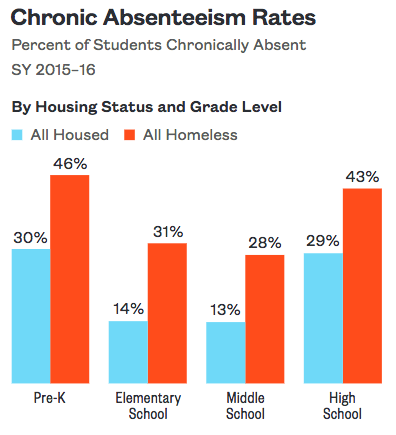

Children of all ages who live in homeless shelters have trouble getting to school. This means that half of students living in shelter are chronically absent, missing 20 or more school days in one year. That’s almost four times the rate of housed students who were not low income.

What is the cause of this chronic absenteeism? Fully understanding why these kids struggle in getting to school requires an individual look at each family, but common threads do emerge.

In one case, a school social work director spoke of a young student who went to school in Brooklyn, but was placed in a Manhattan shelter. If he missed his bus, the bus was late, or if he overslept, he was not able to get to school, as young children are unable to take a long commute to school via public transport by themselves and may not have an adult available to travel with them. This story is representative of one main reason that homeless students have trouble getting to class—their families are placed into shelter far away from their school.

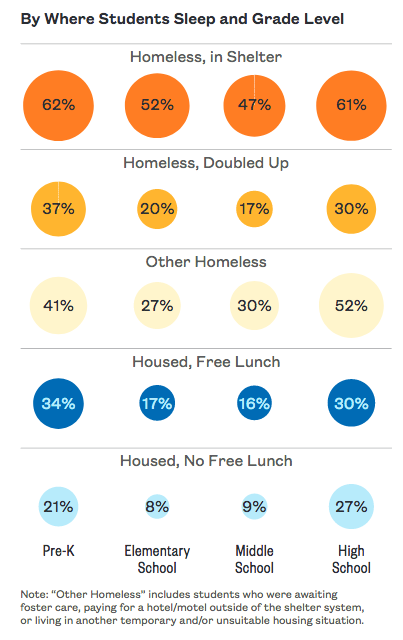

The centralized homeless shelter application center in the Bronx, Prevention Assistance and Temporary Housing (PATH), assigns families to shelters in any of the five boroughs—wherever there is space in a system in which demand outpaces supply. Students are left with two options: transfer schools to be closer to their shelter placement, or travel longer distances to get to school, increasing the risk of frequent absences. Transferring is disruptive to students’ educations, and is generally discouraged by educators, so many students choose the latter. This disconnect between shelter and school location explains why across grade levels, homeless students living in shelter were more likely to be chronically absent than their peers experiencing other types of homelessness, such as living doubled up, as well as more than homeless students overall.

Older students face chronic absenteeism challenges, too—nearly half of homeless high school students are chronically absent. Even though an older student may be able to commute to school by him- or herself, a long commute can still make this difficult. One student we spoke with traveled between a friend’s apartment in Harlem to school in the Bronx every day and had a hard time waking up with enough time for the long commute.

Fixing these transportation and shelter assignment issues in an overcrowded city is difficult, but the City is working to shorten commutes to school for homeless students. One proposal by the Mayor’s office to move towards borough-based shelter applications could make it more likely that families entering shelter remain closer to the schools and other community resources they are used to. More immediately, the New York City Department of Education is investing in supporting homeless students by hiring additional staff and expanding community schools as neighborhood hubs for social services. Children who live in homeless shelters and are moving from place to place need these supports—and others—to help stabilize their educations even when their housing may be uncertain.

Kaitlin Greer, Policy Analyst