Executive Summary

Homelessness is a deeply disruptive experience, but it is especially detrimental to the development and well-being of children. Childhood is often marked by various Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs), or traumatic events that occur between infancy and 17 years of age. ACEs are pervasive, with an estimated 40 percent of New Jersey children having experienced at least one ACE. But they are even more common among children experiencing homelessness. ACEs increase a child’s likelihood of mental and behavioral health issues; however, their impact is not limited to childhood—they have long-lasting effects that follow a person into adulthood.

This report was developed at the request of the New Jersey Coalition to End Homelessness by the Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness. It explores the mental health needs of children living in New Jersey shelters and the connection between homelessness and ACEs. This report also examines how well existing support structures address the unique needs of these children. Relevant mental health programs and approaches for homeless children used in various parts of the country are detailed in the appendix. Interviews with families and shelter staff, and a staff survey reveal that the NJ Children’s System of Care (CSOC), the current means for administering public mental health services to children, does not adequately address the experience of homelessness and living in shelter. Parents and shelter staff alike are frustrated with the barriers and lack of practical awareness of the incredibly challenging and complicated lives of people experiencing homelessness that exist in the current system, such as transportation, long wait times, and numerous other obstacles making it difficult to attend off-site appointments. These barriers prevent many children from accessing the mental health care they need to deal with the trauma and ACEs associated with homelessness.

New Jersey has already shown interest in tackling the negative impact of ACEs through efforts such as establishing the Office of Resilience and implementing an ACEs Statewide Action Plan, which includes strategies like conducting a public awareness campaign and ensuring community input on policy and funding priorities. However, special attention must be paid to the most vulnerable children—children experiencing homelessness. Although families arrive in shelters during their most challenging times, the shelter can serve as a place of opportunity. Here, they can shift their focus from surviving to thriving with the proper social supports. This golden opportunity is the time to link families to services. When it comes to people experiencing homelessness, services delayed are services denied. The Coalition urges the State to invest in the mental health of children in shelter now, as the cost of inaction will be much higher down the road.

Findings & Recommendations

- Ensure on-site, in-person mental health services at shelters are made available and accessible when needed, especially during the critical first stages of engagement

- Collaborate between NJ CSOC and shelters to ensure timely response from the CSOC system for the duration of a child’s temporary shelter stay

- Learn from models with a proven track record underway in other states and localities

- Work to increase the number of NJ CSOC providers who accept Medicaid, as well as providers who treat children five and under

- Collaborate with shelter providers for trainings about child and family homelessness and ACEs for NJ CSOC staff and mental health providers

- Encourage collaboration among mental health, social and human services systems, and providers, health systems, and funders to work in partnership on early interventions for children experiencing homelessness

- Increase staffing at PerformCare, the Children’s System of Care administrator

- Increase outreach to connect with families, such as through campaigns to share information about Medicaid eligibility

Introduction

The experience of homelessness can be a destabilizing force with frequent moves and lost connections to friends, family, and community. Episodes of homelessness during childhood—a critical period of rapid development and growth—can have lifelong negative consequences. The detrimental impact of Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs)—defined as specific types of traumatic events or experiences that occur during childhood—on chronic health problems, mental illness, and substance abuse in adulthood has been well-documented.1 In fact, ACEs have been found to negatively impact education, job opportunities, and future earnings—all issues that have profound consequences on individuals and society as a whole. The financial burden of ACEs-related illnesses is estimated at $748 billion in North America alone.2

This report was developed at the request of the New Jersey Coalition to End Homelessness by the Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness. It combines first-hand accounts and survey responses from shelter staff and parents about the mental health needs of children in shelter, as well as challenges faced in navigating the New Jersey Children’s System of Care (CSOC). Additionally, an in-depth literature review was conducted into the linkages between child homelessness and ACEs, including promising mental health interventions for children experiencing homelessness in other states and localities. Currently, the NJ CSOC is the only avenue for public mental health services for all New Jersey children and though it works well for most, it is not specialized for the needs of homeless children. The following analysis delves into the connection between childhood homelessness and ACEs, barriers to accessing mental and behavioral services while in shelter, and recommendations for improving the current NJ CSOC.

The Link Between ACEs and Homelessness: Losing Stability During Childhood

In New Jersey, it is estimated that more than 40 percent of children have experienced at least one ACE, and 18 percent have experienced at least two ACEs.3 There is a strong association between ACEs and the experience of homelessness, and ACEs are more prevalent in homeless children as compared to stably housed children, further exacerbating their harmful related outcomes.4 Dr. Regina Olasin, Chief Medical Officer of Care for the Homeless, a New York City nonprofit that meets the medical, mental, and behavioral health needs of people experiencing homelessness through shelter- and community-based service sites, notes that while homelessness may not be one of the ACEs, “children experiencing homelessness have everyday exposure to these risks.”5

Children experiencing homelessness are generally more likely than their housed peers to have been exposed to trauma.6,7,8 Unfortunately, children experiencing homelessness are at an even higher risk of onset of mental health issues, such as anxiety or depression, than their stably housed peers.9 According to data from the National Child Traumatic Stress Network, half of school-age homeless children experience anxiety, depression, or withdrawal compared to just 18 percent of non-homeless children.10

Several factors related to the experience of homelessness, such as family instability in the form of domestic violence, community isolation, and the cumulative effects of homelessness, can be considered ACEs. For instance, factors related to life before, during, and after the experience of homelessness are often volatile. Domestic violence is one of the primary reasons families enter shelter.11 Children, regardless of their age, are often privy to the stress and abuse that their parents face, resulting in a trauma response in the child. A child’s well-being can be adversely affected by a parent’s mental illness, which could also impact the child’s mental health in the future. Experiencing maternal mental illness early in life can seriously affect healthy brain development in a child, which can lead to poor education outcomes later in life.12 These impacts are exacerbated when other factors associated with homelessness are involved, such as deep poverty.13

Additionally, events like frequent moves and separation from family and friends can also lead to exposure to traumatic experiences. Children of all ages who experience homelessness are also at risk of isolation, both due to the nature of being removed from their typical social environments as well as due to related bullying and victimization by peers.14 Experiencing homelessness is often associated with losing connections to friends and other stabilizing elements like their afterschool activities, team sports, and religious institutions that tie children to their peers and their communities.15,16 When children move from place to place, they are too often disconnected from their school environment, which typically connects them to a support network of friends, teachers, and other responsible adults who look out for them, one aspect of the entire family’s loss of a social support system. Further indicating the increased risk of social isolation, studies also show that children who have experienced homelessness are more likely than their peers to experience victimization, which involves an imbalance of power that is repeatedly enforced among peers, often through overt or interpersonal means, such as being threatened with violence or gossiping.17,18 Many then subsequently respond through aggressive behaviors or by victimizing other children.19

Adverse childhood experiences, like those tied to homelessness, can often build upon each other, leading to toxic stress.20 Intense and prolonged stress surpasses what can be considered tolerable for a child to cope with, leading to a response where the child’s body and mind are continually on high alert.21 As this wear and tear impacts the body, a child’s development is hampered, with impacts that can last into adulthood.

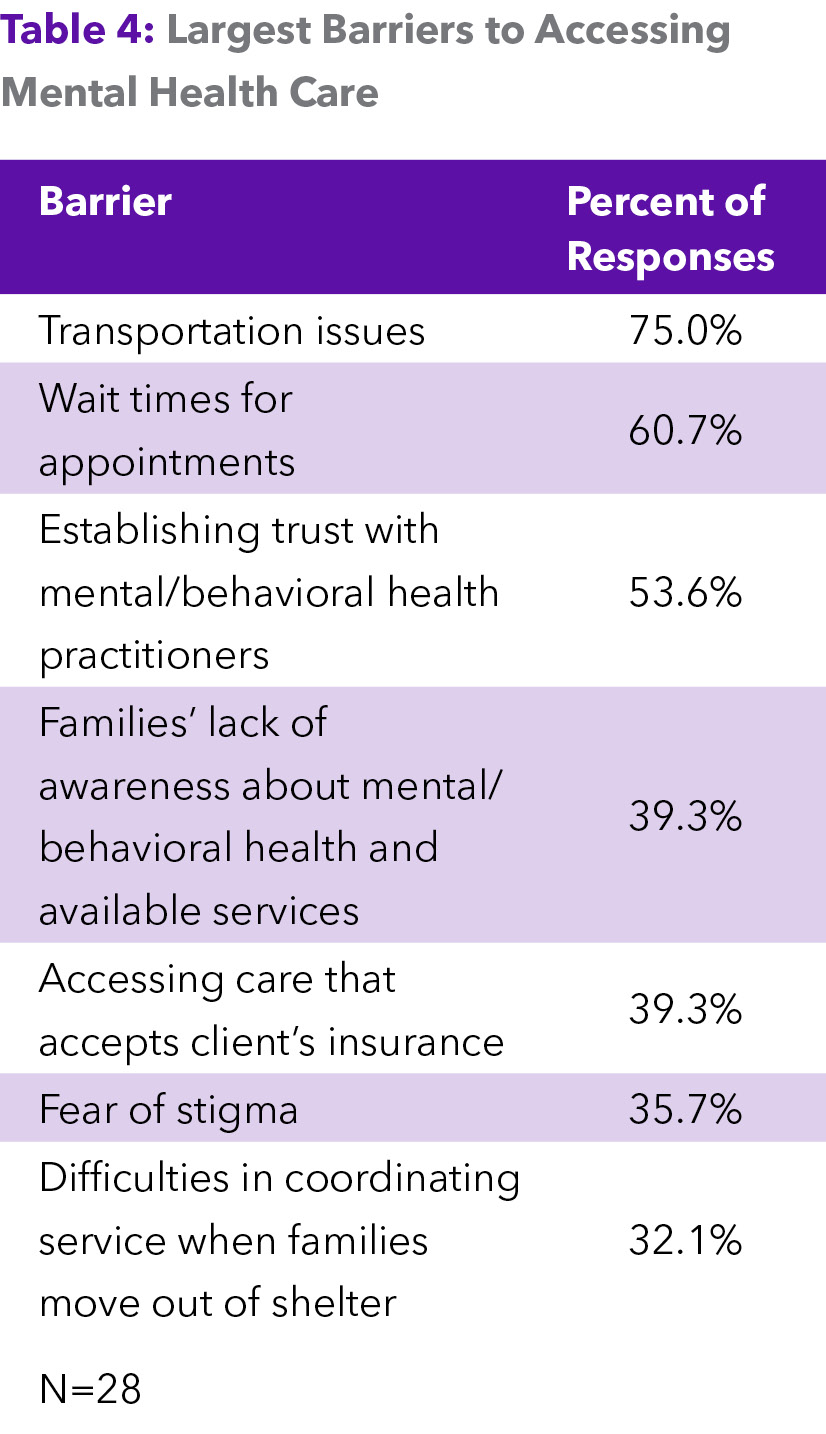

Barriers to Mental Health Services for Homeless Children

Homeless children have fewer resources than their housed peers, even when adjusting for poverty.22 Financial and logistical obstacles can prevent children and their families from accessing necessary services.23 Financially, homeless families can struggle to navigate the healthcare system due to being uninsured. They may be unaware that they qualify for mental health services. The logistical barriers to care are extensive but can include inadequate access to transportation, inconvenient scheduling, limited service hours, and lack of childcare.24 (See Appendix, Table 4). Unfortunately, CSOC does not currently accommodate the experience of homelessness and living in shelter. This lack of access further places children who are experiencing homelessness at a disadvantage when seeking help.

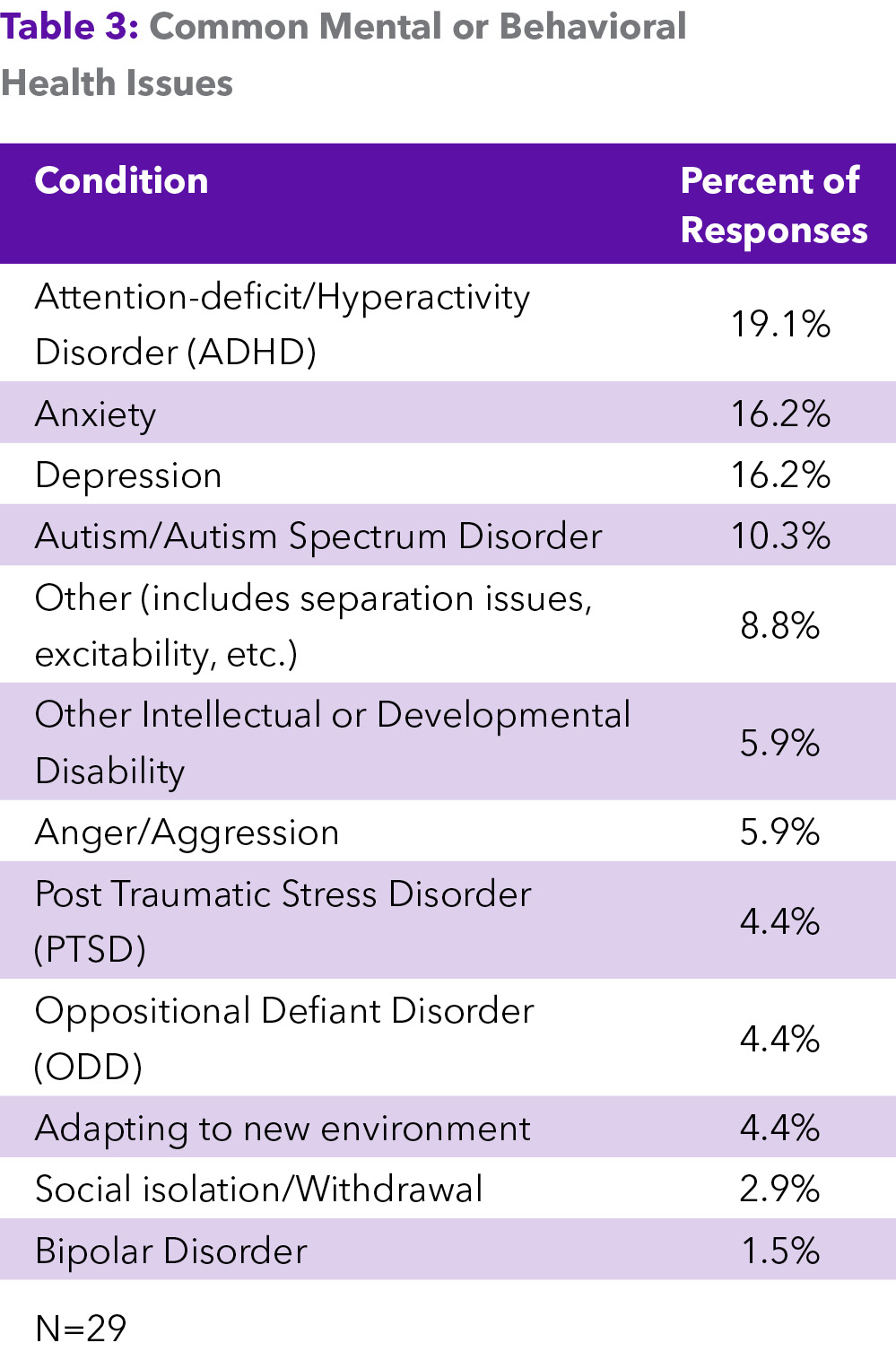

Based on interviews conducted with families and staff and the staff survey, children in NJ shelters are dealing with various developmental and mental health needs (See Appendix, Table 3). Over 35 percent of responses mentioned the most common behavioral health need as some form of developmental disorder, with almost 20 percent of responses mentioning Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). About 32 percent of responses mentioned children dealing with anxiety or depression. It is important to note that all these conditions have unique diagnostic requirements and age eligibilities, but many of their symptoms overlap, especially in young children. Although a child’s social isolation or withdrawal may prompt their family to seek services, that can be a symptom of either or both a developmental or mental health disorder.

Families and staff at the shelters surveyed often remarked on how difficult it is to access care in their towns and counties due to problems with transportation in their area. A large proportion of respondents, about 75 percent, cited transportation as one of the most significant barriers to children receiving mental and behavioral health support while in shelter (See Appendix, Table 4). As stated by a shelter provider, when families are dealing with the daily realities of living in deep poverty and experiencing homelessness, “it’s really hard to wrap your head around how much of a barrier it is to get to your appointment across town a week and a half from now.” Many shelters are in areas with limited access to public transit, and the options available do not run frequently enough to get families to their appointments on time. Additionally, parents in shelter often lack access to a car, eliminating the option of driving to a provider’s office for many in this situation.

Time itself is another crucial barrier to children receiving behavioral health care while in shelter. Many staff who were surveyed, about 61 percent, stated that the wait times for appointments presented a significant barrier to families accessing care. New Jersey shelters typically aim to move families out within 60 days of their arrival. However, families were often unable to secure confirmed appointments prior to moving out. When services with CSOC took too long to set up, families often lost touch with whoever was assisting them in accessing services. As families exit shelter, they are hit with a whirlwind of priorities, such as settling into their new living accommodations, affording rent and food, and ensuring they could meet other essential needs. About 30 percent of survey respondents mentioned that it was challenging for families to coordinate care after they left shelter.

Families with multiple children also noted that childcare is another barrier to receiving mental health care. Parents note that they feel they must choose among their children’s needs because they do not have access to safe, reliable childcare for their other child(ren) that would enable them to accompany the child in need to therapy appointments.

When families can connect to care, it is often in a form that does not meet their needs. Although telehealth therapeutic services have helped expand access to more remote areas of the United States, many parents lament that most therapists who take their insurance operate primarily or entirely through virtual services. Telehealth services became a more prominent method of providing care across multiple medical fields during the initial COVID-19 public health emergency.25 Many shelter staff members note that parents want to see someone in person. This relates closely with the third most common barrier selected by surveyed shelter staff: establishing trust with their mental or behavioral health provider. Parents noted that their child could not establish a trusting rapport or emotional connection with their therapist via video call. This is ultimately harmful to the child, as their visits during the family’s shelter stay should serve to build a connection with a provider who they can continue to see after they exit shelter.

These barriers lead to apprehension from staff about CSOC. Though staff members are confident in their skills in referring families to mental healthcare, about 70 percent of those surveyed reported that they did not consider CSOC easy to navigate. About 80 percent do not consider any previous training they have received from CSOC helpful. One shelter staff member expressed frustration when recounting a moment when they “spent their currency” or the trust and interest they had built up with the parent to seek services, only for the parent to be let down during or immediately after the intake call with CSOC. When apprehension is high and confidence in the system is low, staff members spend their valuable time trying to find outside resources to which they can direct families. One shelter director said, “I have to push my staff to encourage families to try to use the [Children’s System of Care] because my staff is burned out on the concept that it will ever work.”

Overcoming Barriers: Meeting Families Where They Are with Mental Health Services

“Family shelters are with the family [during] their most turbulent times; they have often hit rock bottom, but it can be a turning point. And so, it feels so logical to have a greater connection to care there.” –Family Shelter Director

For many families experiencing homelessness, a shelter stay is a perfect opportunity to address their children’s mental health needs. Often, a child and their family’s time in shelter is the first opportunity to receive consistent care from a mental health professional, rather than seeking care in an emergency room. Furthermore, people experiencing homelessness often feel invisible and typically do not seek help or input from “establishment sources.” A shelter staff member said that families often feel “mistreated by institutional systems” they have worked with in the past. That sentiment can be intensified when a family looks for help on sensitive matters like mental health, in which building trust is crucial to offering services and building a provider-patient relationship. In the words of a shelter administrator, “You have to have an ongoing relationship with someone who’s going to provide you with that level of care in order to see a difference.” They are much more open to guidance from shelter staff they see every day than someone they may consider a stranger, in this case, an outside mental health provider. Although many families who enter shelter are experiencing their most turbulent times, a shelter stay can be seen as a moment of opportunity, during which they can build toward stability. Families can focus on thriving instead of surviving, but only if supported by the proper resources. Without the all-consuming struggle to meet their basic needs, such as food, a bathroom, a place to sleep, and ways to stay safe, parents are more likely to focus on signs of mental trauma in their children. A shelter stay provides for a family’s physical needs, allowing them to prioritize mental health.

There has been a growing awareness of the importance of addressing the mental health needs of children experiencing homelessness throughout the United States. Nonprofit service providers, as well as many local and state governments, have recognized that a child’s time in shelter is ripe to reach them with critical mental and behavioral health services that can limit the impact of the difficult experiences they face. These models offer promising approaches to mental health care for children in shelter that New Jersey could take cue from (see Appendix, Section 3). Family shelters stand by parents and their children, providing support during their most turbulent moments, and can serve as a stimulus for taking steps toward long-term stability. Connection to mental health services within the shelter is vital to families as they work to develop the necessary systems of support that will keep them from returning to shelter. Shelter staff devote much of their time to building trusting relationships with families. Some shelter providers emphasize the need to meet children and their families where they are by integrating mental health services into their array of in-house services, as it ensures that issues like transportation and psychological barriers do not obstruct them from seeking treatment. The trust between the family and the shelter can be leveraged to lend credibility to the mental health provider that operates in-shelter, further supporting the establishment of a relationship between client and provider.

Other programs emphasize the need for in-shelter services by referring parents to nonprofit providers that operate in the same location as the temporary housing or shelter accommodations. Whether clinicians visit the child or the mental health provider occupies a space in the facility, the low threshold to access care ensures that parents can get their kids the targeted support they require. As one shelter director put it, “The system is not mindfully trying to exclude families [in shelter].” However, as parents are often dealing with the “mental load” of homelessness and sometimes coping with their own thoughts of feeling like “an abject failure as a parent,” any impediment to care can be very discouraging. Families should not have to jump through hoops to get their children access to the mental health care they need.

>> For details on various programs and models tackling homeless children’s mental health, refer to the Appendix, Section 3, “Promising Approaches to Mental Health Care for Children in Shelter.”

Consequences of Neglecting the Mental Health Needs of Homeless Children

Neglecting the mental health needs of children experiencing homelessness can have broader systemic implications, leading to future strains on healthcare, education, and other systems. The individual consequences for the life of the child include impaired physical and cognitive development, lower education attainment, and increased risk of suicide.26,27,28

Children exposed to trauma have a higher chance of repeating a grade in school and facing learning difficulties.29 Children who experience homelessness are especially vulnerable to low educational attainment compared to their peers. Homelessness at a young age can be a significant “disruptor” to learning during the early years of schooling.30

The accumulation of ACEs, like the experiences related to homelessness and prolonged exposure to stress, can severely impact a child’s development. Children exposed to toxic stress early in their lives may go on to experience problems with developmental delays and emotional regulation as compared to their housed peers.31,32 These outcomes can continue to impact a person’s health and social outcomes throughout their life. In addition to an increase in chronic diseases, experiencing a high number of ACEs as a child can increase the risk of experiencing homelessness as an adult.33

The consequences of inaction are tremendous. According to the 2023 Point-in-Time estimate for New Jersey, a staggering 4,000 people in families with children experienced homelessness, either unsheltered or in emergency shelter or transitional housing, on a single day in January 2023. Even more alarmingly, 2,460 of these individuals were under 18 years old.34,35,36 ACEs during childhood homelessness can compound over time. Therefore, the care needs of homeless children are multipronged, and the impact that these traumatic events can have on their mental health and well-being is varied. The care teams helping these children must have the specialized knowledge and tools to assist them, from an understanding of ACEs and their connections to homelessness to the justified fears, barriers, and traumas faced by their parents. One interviewee stated that “most clinicians within the system are not familiar [with family homelessness],” but the few who possess specialized knowledge about homelessness and deep poverty are often “amazing advocates for their clients.”

In contrast, interacting with clinicians who do not have specialized knowledge about family homelessness can sometimes expose parents to undue surveillance. A shelter director shared a few experiences during which families were flagged to NJ’s Child Protection and Permanency (DCP&P) agency due to their experiencing homelessness, subjecting them to interviews about the welfare of their children. Children and their families deserve accessible, compassionate assistance that won’t jeopardize their ability to stay together.

Findings and Recommendations

- Ensure on-site, in-person mental health services at shelters are made available and accessible when needed, especially during the critical first stages of engagement when trust and relationship building must be established

- Collaborate between NJ CSOC and shelters to ensure timely response from the CSOC system for the duration of a child’s temporary shelter stay

- Learn from models with a proven track record underway in other states and localities (For information on these models, refer to the Appendix, Section 3)

- Work to increase the number of NJ CSOC mental health providers who accept Medicaid, as well as providers who treat children ages five and under

- Collaborate with shelter providers for trainings about child and family homelessness and ACEs for NJ CSOC staff and providers—from mental health practitioners to PerformCare representatives

- Encourage collaboration among mental health, social and human services systems, and providers, health systems, and government and philanthropic funders to work in partnership on impactful early interventions for children experiencing homelessness

- Increase in staffing at PerformCare, the Children’s System of Care administrator

- Increase outreach to connect with vulnerable families and communities, such as through campaigns to share information about Medicaid eligibility

On-site, in-person services, instead of remote services, would help providers build the trust necessary in a patient-practitioner relationship. Several promising models operate in the United States from which New Jersey could take a cue.

As mentioned previously, transportation is a common barrier to families being able to access mental and behavioral healthcare. On-site, in-person services, as opposed to remote services, would help address the need for in-person services that are accessible to families without means of transportation. This can be accomplished without requiring a provider to be permanently present at the shelter. During the interviews, many staff mentioned that families and children want to meet with a mental health provider in person to build the trust necessary in a patient-practitioner relationship. Some staff even said that providing therapy to families remotely is simply just not as effective as providing services in person. One parent interviewed mentioned that she switched her child’s provider as they were not able to connect during their remote sessions and instead looked for an in-person provider. Several promising models operating in the United States could inform future implementation of on-site mental health services at all shelters that work with families (See Appendix, Section 3).

Expanding the network of mental health providers that accept Medicaid could help reduce the long wait times for families.

Additionally, families and shelter staff note that a significant lack of providers accept Medicaid. As CSOC’s provider network manager, PerformCare may focus additional efforts on developing provider networks, perhaps recruiting more providers to enroll to deliver care to patients with Medicaid. Particular attention should be paid to recruiting providers specializing in treating very young children, as parents especially noted frustration when trying to find a practitioner who serves children under five. Expanding the network of providers could also help with the long wait times for care. Families should not face a lack of quality care due to their inability to pay out of pocket or with private insurance.

Mental health providers and PerformCare staff must have exposure to the topic of homelessness and its complexities.

Recruiting new mental health providers is not enough to expand the pool of professionals equipped to address the unique challenges of children experiencing homelessness. Robust training, in collaboration with shelter sites, for both mental health providers and PerformCare representatives, in topics related to family and child homelessness is crucial in reworking a system that has mistreated people like those in shelter. Clinicians especially need to be able to meet clients halfway and not allow preconceived notions about homelessness to impact their service.

Hiring more staff at PerformCare could allow staff to have the time necessary to build and maintain relationships with families seeking their stewardship in care.

An increase in staffing at PerformCare could also address delays in follow-up. Parents especially noted valuing the care management that they receive from PerformCare staff. One parent mentioned that she appreciated the follow-up she received from a particular PerformCare staff member, even when the updates were not news that the parent wanted to hear. However, when this communication falls off, it can be very frustrating and demoralizing for parents. Hiring more staff could allow for the personalized stewardship that is often needed when a family is seeking mental or behavioral health services for their child.

The New Jersey Children’s System of Care and the Department of Children and Families have a responsibility to educate families about services and the nature of children’s mental and behavioral health.

Increased community outreach and education for families could also help address the gaps noted by parents and staff. Regarding outreach, many staff indicated during interviews that families were unaware of the fact that they were eligible for free therapeutic services for their children. Although New Jersey is a Medicaid expansion state, many parents, through no fault of their own, are under the misconception that services must be costly.37 This makes them even more hesitant to seek help when their children need it. Families in shelter already face many barriers, but not understanding what they are eligible for further hampers their ability to access care. Shelter staff do their part in educating families and making them aware of services, as many families do not know mental health care assistance exists until they enter shelter. However, the responsibility should also lie with the New Jersey Children’s System of Care and the Department of Children and Families to market these services and ensure the public knows what is out there. The system also has a responsibility to educate families about children’s mental and behavioral health. Shelter staff noted that parents were often unaware of what symptoms to look for before reaching out to PerformCare. It is especially pertinent considering how varied early symptoms of children’s mental health challenges can be and how they often overlap with developmental challenges.

Conclusion

Homelessness in children is associated with multiple adverse behavioral, mental, and educational issues that research has shown all too frequently have a negative impact on their health and well-being into adulthood. Children experiencing homelessness deserve the collective action of stakeholders to ensure they receive the targeted mental health services that account for their unique experiences and living situations.

The harmful effects of experiencing homelessness as a child can be reduced. The brain’s neuroplasticity, or ability to be “rewired” or build new neural pathways, suggests that proper early intervention can prevent, relieve, and treat the negative consequences of homelessness.38 New Jersey has demonstrated its focus on addressing the impact of adverse childhood experiences by committing to a statewide strategic action plan and forging partnerships to prevent and reduce childhood adversity and increase public awareness.39 However, special attention must be paid to the most vulnerable children—children experiencing homelessness. Although families arrive in shelters during the most challenging moments of their lives, shelter can serve as a place of opportunity, where they can shift their focus from surviving to thriving with the proper social supports. In-shelter mental health services for children remove the barriers that can keep families from taking the crucial steps to tackle their child’s mental health needs and ensure that the impact of homelessness is addressed early and effectively.

New Jersey’s Children’s System of Care and its program administrator, PerformCare, provide a solid foundation for delivering public mental health services for most residents. This makes it uniquely positioned to act on these recommendations to mitigate the future negative consequences for today’s children in shelters. The New Jersey Coalition to End Homelessness urges the State to invest in the mental health of children in shelter now, as the cost of inaction will be much higher down the road.

The directive is clear: Commit to the mental health needs of homeless children now or compensate later.

Appendix Section 1: Methods

Member organizations of the New Jersey Coalition to End Homelessness were contacted to ask for their participation in the survey and interview. To understand the New Jersey Children’s System of Care (CSOC) overall and how families and shelter staff interact with the system to access care for children, staff at shelters across the state answered a questionnaire and were invited to speak further with the authors about their experiences. Case managers approached parents at shelters to determine their interest in an informational interview. Staff and parent participation in both the interview and survey was voluntary. Clients were offered a $20 gift card as compensation for their time. Staff were not offered an incentive to participate.

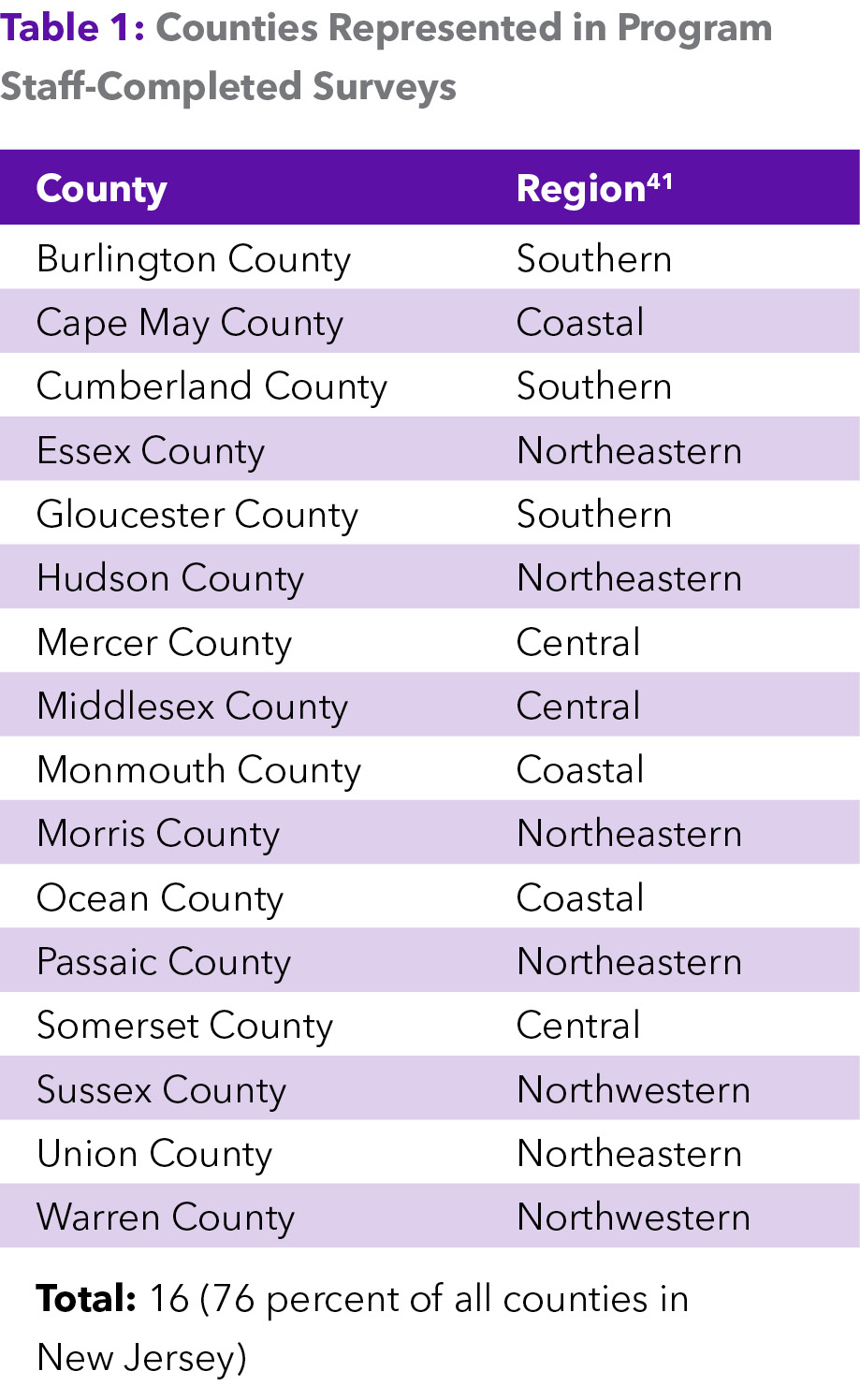

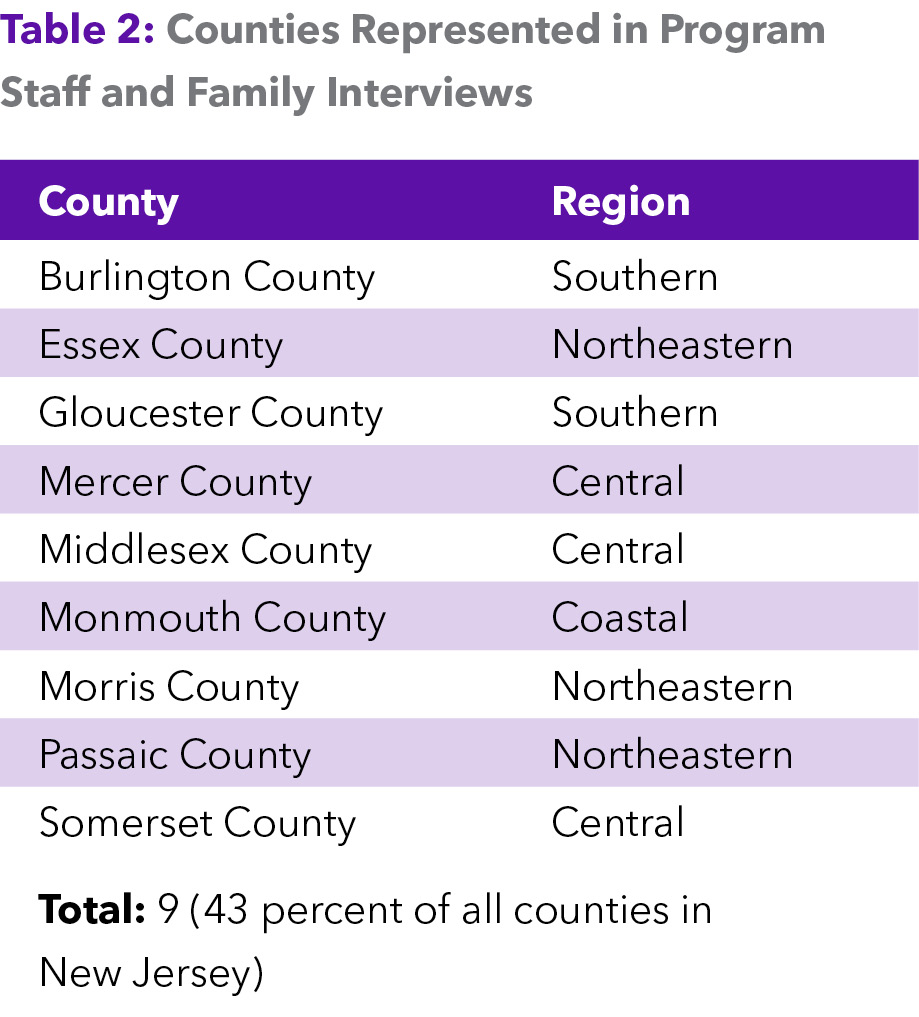

The authors interviewed parents and shelter staff in 11 shelters in nine out of 21 counties in New Jersey (43 percent of all counties).40 Respondents identified critical points of friction in their experiences navigating mental health resources for children, particularly those connected to the New Jersey Children’s System of Care (CSOC) administered by PerformCare. Additionally, 37 shelter staff members across 16 counties (76 percent of all counties in the state) completed surveys about their experiences supporting families. The tables below outline key findings. Please contact the New Jersey Coalition to End Homelessness for additional survey details.

Appendix Section 2: Results

Appendix Section 3: Promising Approaches to Mental Health Care for Children in Shelter

The following is a more detailed overview of several programs and initiatives that exist in the United States to support the mental health needs of children living in shelters and experiencing homelessness. While these are some of the most promising programs, it is not an exhaustive list of all the efforts to address the mental health needs of homeless children that are operating across the country.

New York City, New York

New York City has an extensive shelter system for families with children, composed of facilities operated by local government agencies or contracted nonprofit providers. Many shelters offer some form of mental health services within their facilities. However, offering this care has historically depended on the resources of the operating organization, as funding and regulations from the NYC Department of Social Services (DSS) have often prevented social workers from providing therapy.42 Recent efforts have attempted to improve how mental health services are administered throughout this vast network of shelters.

Client Care Coordinators (CCC) were introduced as part of New York City’s ThriveNYC initiative under Mayor Bill de Blasio in the mid-to-late 2010s. These licensed social workers were placed in Families with Children shelters and tasked with helping families deal with “the stressors and anxiety induced by homelessness.”43 While their job descriptions were initially expansive and included providing short-term counseling to families, their roles shifted over time. Today, most CCCs provide biopsychosocial assessments and then refer families to mental health services within the community.44

In 2022, additional steps were taken to bring on-site mental health services to family shelters. The New York City Council introduced legislation requiring on-site services in every family shelter.45 Enacted in 2023 as Local Law 35, it is slated to be implemented first at the 30 largest family shelters by July 2024 and then at all family shelters by 2025. This new legislation dictates that the mental health provider-to-family ratio cannot exceed one provider for every 50 families. It also requires that the Department of Homeless Services consult with shelter operators to determine the type of mental health professionals needed at the facility.46 Implementation was temporarily stalled due to the law being unfunded and subject to appropriations during early 2024. As of May 2024, the largest shelters have been instructed to begin hiring the required mental health staff. However, some providers have indicated that they did not receive substantial directives from the Department of Homeless Services (DHS).

Boston, Massachusetts–Boston Healthcare for the Homeless Program

Boston Healthcare for the Homeless Program (BHCHP) is composed of hundreds of service providers who work to restore the health of families experiencing homelessness.47 It delivers trauma-informed care in a range of languages to families and youth at roughly 80 sites—family and domestic violence shelters, hotels, and motels—across Boston.48,49 Unique to their provision of behavioral healthcare, BHCHP offers same-day, walk-in mental health care, which ensures that families have a low threshold to access care.

In 2023, BHCHP partnered with Horizons for Homeless Children, Massachusetts’s leading organization serving homeless children, to open a family clinic at one of their centers in order to bring healthcare directly to families.50,51 BHCHP credits the utilization and quality of their services to their proximity to the other services that families are receiving at Horizons. Their location and method of service provision help to break down a family’s potential “psychological barriers” to receiving mental health support, as mental health assessments are regularly woven into general medical visits at the clinic.52 Additionally, it allows for a centralized location where families can access mental healthcare services, further ensuring there is the necessary continuity of care in a familiar setting with a familiar face.53 At the Horizons location, the clinic has also implemented services for both parents and children, such as parenting groups and play therapy for children, among other supports.

North Carolina–Project CATCH

Project CATCH (Community Action Targeting Children Who Are Homeless) in North Carolina came about after staff at the Salvation Army of Wake County realized that children at the location were experiencing difficulties like an inability to focus or feelings of anger.54 Prior to CATCH, staff at the site struggled with identifying the signs of mental illness or developmental delays in children. Those who did recognize a child’s needs faced the lack of a complete, shared source of information listing what services were available in their region. Project CATCH works collectively among the Salvation Army of Wake County, Young Child Mental Health Collaborative, Wake County SmartStart, and other child advocates to support the mental health needs of children living in emergency shelters and transitional housing.55

Shelters in the Wake County area refer families to CATCH, which then schedules a screening with the child. Speed is a prominent feature of the program, as a CATCH case manager typically responds to the request within two days of the shelter’s initial call.56 After screening the child and gathering related school and medical records as well as questionnaires from parents, case managers help make referrals to local educational or mental health resources.

Project CATCH extends its services by providing professional development opportunities to staff and engaging programming to parents. It assists in bringing trauma-informed training to shelter staff that further bolsters their ability to identify the mental health needs of children at their facilities. Parents benefit from participating in programs that help strengthen their parenting skills in areas such as communication, problem-solving, and interpersonal relationship building.57

Florida–Lotus House

Lotus House, the largest women’s shelter in Florida, recognizes that the majority of its clients have experienced severe trauma, such as domestic violence and abuse.58 To address this need, it offers counseling and therapy for families, singles, and youth. Among various therapeutic services, families have access to parent–child therapy, where the child and parent can work together with the therapist. Counselors provide services in Lotus House’s play therapy rooms, designed to center the child through appropriately sized furniture.59 Its trauma-informed services focus on providing a safe environment that facilitates a family’s healing.

A study evaluating the impact of Lotus House’s trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy (TF-CBT) or parent-child interaction therapy on families within the homeless shelter found that participating in either type of therapy helped reduce children’s behavior problems.60 The study notes that there was a particular effort to complete therapy within 10–12 sessions, given the fact that families tend to cycle in and out of shelter. When surveyed by trained staff (independent of those who provided the families with therapy), most families reported satisfaction with the treatment.61

California

The Homeless Children’s Network (HCN) Ma’at Program is a hub for homeless agencies in San Francisco that look to HCN to provide mental health services and support to children and families experiencing or at risk of homelessness or formerly homeless.62 With a particular interest in bringing Afri-centric care to Black families in San Francisco, the network works to build and maintain relationships within the community, engaging their partner agencies on an ongoing basis. The Ma’at Program offers families direct mental health services for their children, as well as community engagement, knowledge building, and events that promote overall wellness.63

The referral process for Ma’at’s mental health services takes roughly one to two weeks, where program staff focus on gathering demographic information and assessing the clients’ behavioral and mental health concerns.64 The program then works with the family to build a relationship before administering what it refers to as “whole person behavioral health.” The culturally responsive and patient-centered services provided by Ma’at have been shown to help participants remove the stigma of receiving mental health services, with participants being highly satisfied with the services.65 Children who received services from Ma’at reported that talking with their therapist helped them “feel better” and build self-love.

Minnesota–The Early Risers Program

The Early Risers Program is an intervention initiative for homeless elementary school children and their families living in supportive housing that aims to help reduce children’s behavioral issues by promoting positive parenting.66 Parents, with their children, are trained on how to respond to a child’s behavioral problems. Parents learned effective communication and problem-solving skills. Children received services via an afterschool program and summer camp. The children’s activities used the “Promoting Alternative Thinking Strategies” (PATHS) curriculum, which aims to reduce aggression and promote self-control and positive self-esteem.67 A randomized trial conducted on the program revealed that families who participated saw a decrease in parents’ perceptions of their child’s depression. Parents also reported a reduction in the worsening of the child’s conduct problems.68 Additionally, parents reported feeling more confident in their parenting skills.

New York City, New York–Care for the Homeless

Care for the Homeless is a nonprofit dedicated to bringing essential medical, mental, and behavioral health services to people experiencing homelessness, including children.69 They use the PRAPARE (Protocol for Responding to & Assessing Patients’ Assets, Risks & Experiences) risk assessment tool to screen patients on several sensitive topics related to their health and housing status.70 The data collected is used to evaluate the patient’s needs, including referrals for other services.71 The organization then provides interventions such as cognitive behavioral therapy to treat depression and other mental health issues.72

Seattle, Washington–Mary’s Place

Mary’s Place operates shelters in the Seattle/King County area of Washington state, providing “enhanced shelter” with various services available to women and families with children. The organization offers both generalized in-house behavioral health services and treatment navigation, as well as more specialized support from outside providers. Recognizing the importance of on-site behavioral health services, Mary’s Place staff build partnerships with local behavioral and physical health providers to bring screenings and treatment, particularly developmental services. These services are prioritized for families with children under three years old, among other vulnerable types of families. The in-house behavioral health team assists families in accessing care and creating individualized plans for their long-term success. The children and youth services team’s work is notably helpful in establishing trust with families. Many families mention in their exit surveys that they appreciated the genuine care and connection staff showed to their children. The support provided to children often helps bridge the gap between parents and other adults in the family that may be hesitant to engage with shelter supports.

Notable in its approach is its incorporation of trauma-informed practices and its understanding of the link between racism and homelessness. Given the prevalence of trauma among people experiencing homelessness, especially among young children, all of Mary’s Place’s programs incorporate techniques to reduce the trauma that is associated with homelessness and work to create a safe and empowering space for families. Mary’s Place staff are careful not to collect information during intake that could risk re-traumatizing families and their children. Families are enabled to make their own choices as involvement in all services is voluntary, except for housing assistance. According to Mary’s Place, although King County’s population comprises only about 35% of people of color, almost 90% of its clients are from such communities. This understanding informs the work of its staff, who also seek relevant services from organizations led by people of color.

This report was developed in partnership with the New Jersey Coalition to End Homelessness by ICPH.

Note: Citations and sources for data are included in the PDF version of this document available by clicking Downloads underneath the Table of Contents.