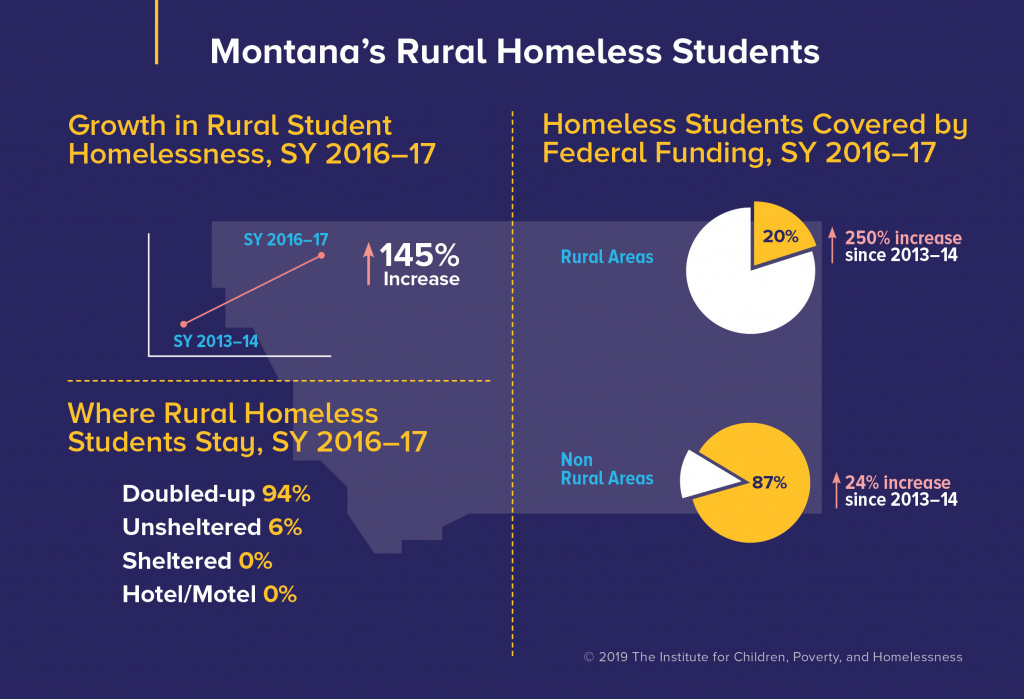

Across America, the number of students experiencing homelessness in rural communities is rising at an unprecedented pace. Montana saw a staggering 145% increase between school years 2013–14 and 2016–17—more than 48 times the 3% national growth rate and second only to Nebraska’s 200% increase. But what accounts for this rapid ‘growth’?

Indisputably, the increase of student homelessness exposes an underlying crisis of housing instability faced by many rural communities. Nevertheless, in some states, large year-to-year increases in the number of homeless students—as is the case in rural Montana—can be attributed improved identification practices rather than a sudden surge.

Starting in 2012, Montana’s Office of Public Instruction implemented several changes in how it identifies and supports this segment of the student population, beginning with increased efforts to effectively communicate with school personnel, from superintendents to bus drivers. “If they have anything to do with school, I have gone and talked to them about homeless kids and why it’s important to find them and identify them,” explains Heather Denny, the State Homeless Education Coordinator. In her work, Denny has also placed a greater emphasis on providing technical assistance to ensure that school districts understand the requirements of the McKinney-Vento Act, a federal law to ensure the enrollment and educational stability of homeless children.

Family and community outreach are as important as improving communication with school personnel. Montana’s Education for Homeless Children and Youth Program rebranded federal documents with state-specific examples to assure resources were applicable to the region. Coordinators placed a strong focus on cultural sensitivity and building trust, particularly when working with Native American communities to provide outreach and services. “You have to be both persistent and consistent,” says Denny.

Identifying and supporting homeless students is most successful when districts have access to needed resources, but the application process can be long and complex. Simplifying the McKinney-Vento subgrant application process, and thereby making subgrants more accessible to school districts, was another big step Montana took to better serve their rural homeless students. “If your grant application is so complicated that it takes a grant writer to successfully navigate the process,” explains Denny, “then you’ve cut out your smallest, most resource-challenged districts,” who cannot afford to hire a grant writer.

Besides making the application more user-friendly, Montana also reduced the minimum requirement for a school district to apply for a subgrant, allowing districts to qualify with either a minimum of 50 identified homeless students or if 10% of the student body is homeless. “That allows a district that only has 100 kids, but 10 of them are homeless, to apply for grant funding,” says Denny. Extra weight was given to school districts in communities in deep poverty or with high unemployment. After these changes were implemented, the number of rural homeless students covered by a subgrant increased 250% in three years. Measures like these are of monumental importance in sparsely populated but struggling communities that can otherwise be overlooked by funding allocation formulas.

While the rapid growth of rural student homelessness is an alarming reflection of the national crisis of housing instability faced by rural communities, it may also be indicative of the hard work and dedication of those like Heather Denny and her staff to identify and support every student experiencing the trauma of homelessness. Once identified as homeless, a student can be connected to much-needed services, such as transportation or academic tutors. Identifying and serving homeless students is particularly crucial in rural communities, where resources and infrastructure are often limited, and schools are frequently the only reliable source of support for children experiencing homelessness. More states can look to Montana’s Education for Homeless Children and Youth Program as an example of how a community, with determination and a locally tailored approach, can respond to the alarming crisis of student homelessness. As Denny wisely noted, when it comes to homeless students, “you need to identify them so you can get the right interventions to the right students.”